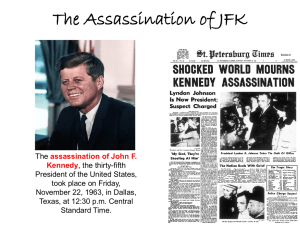

Postmodernity, History, and the Assassination of JFK

advertisement