our response in full (Word) - Equality and Human Rights Commission

advertisement

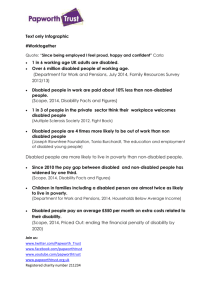

National Skills Forum Research on Skills and Social Inclusion Evidence of the Equality and Human Rights Commission on Skills and Training for People with Disabilities December 2009 For more information please contact: David Coulter/ Anne Madden Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Tel: 0161 829 8542/ 0161 829 8565 Email: Anne.Madden@equalityhumanrights.com/ David.Coulter@equalityhumanrights.com 1 2 Background: The Equality and Human Rights Commission The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC), established on the 1st October 2007 is working to eliminate discrimination, reduce inequality, protect human rights and to build good relations, ensuring that everyone has a fair chance to participate in society. The Commission brings together the work of the three previous equality commissions, the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC), the Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) and the Disability Rights Commission (DRC) and also takes on responsibility for the other aspects of equality: age, sexual orientation and religion or belief, as well as human rights. The EHRC is a nondepartmental public body (NDPB) established under the Equality Act 2006 – accountable for its public funds, but independent of Government. Introduction The EHRC is responding to the invitation from the National Skills Forum for written evidence on the provision of, and access to, skills and training for disabled people, as well as the effect skills and training has on the progression of these learners into the labour market. The EHRC welcomes this opportunity to contribute to research into skills and social inclusion. We have drawn upon research produced by the EHRC, as well as research undertaken by the Disability Rights Commission and research produced by our stakeholders. We are concerned at the slow progress in improving learning and work opportunities for disabled people. A recent review commissioned by EHRC found that 1: Disabled people are still only half as likely as non-disabled people to be qualified to degree level and are twice as likely as non-disabled people to have no qualification at all. Inequalities in the proportions of disabled and non-disabled people in work persists, with only half of disabled people in work, compared with over four fifths of the non-disabled population. 1 Early Years, Life Chances, and Equalities: a literature review, Johnson, P., Kossykh, Y., Frontier Economics (2008). 3 Evidence on the provision of, and access to, skills and training for people with disabilities. DRC research in 2007 2 found that 23% of disabled people lack functional literacy, compared with a national average of 16%. 31% lack functional numeracy compared to national average of 20%. And one fifth of young disabled people said they were discouraged from taking GCSEs because of their impairment. Young disabled people are twice as likely to be not in education, employment or training (NEET) at age 16 as their non-disabled peers, which increases to three times as likely by age 19. Not being in employment, education or training at 16 is the single most reliable predictor of unemployment at age 21. Only 9.5% of learners in LSC-funded provision are disabled, compared to 20% of the working age population being disabled. Disabled people are underrepresented and less likely to complete their courses in the national Train to Gain programme. More than a third of those with no qualifications are disabled. Disabled people are twice as likely as other citizens to have no recognised qualifications and only 59% are qualified to at least level 2, compared to 76% of non-disabled people. Disabled young people have broadly the same chance of achieving a level 2 qualification as a non-disabled young person3. However there is a marked inequality of outcome in attaining higher level qualifications. This reflects the much higher rates of dropping out of education at age 16 and above among disabled people. According to the Learning and Skills Council 4, of young people not in employment, education or training, and who consider they have a learning difficulty and/ or disability and/ or health problem, 2/3 are males and 1/3 are female. By contrast young people not in education, employment or training who do not consider they have a disability broadly reflect the gender profile of the age cohort. 2 Figures in this section are taken from Disability, Skills and Work : Raising our Ambitions. Evans, S. Social Market Foundation/DRC (2007). The data is sourced from the Households below Average Income Statistical report (HBAI) for the period 1994/95-2005/6 and from the Labour Force Survey, Spring 1998-2005. 3 Labour Force Survey. ONS (2007). 4 These statistics are taken from ILR/SFR 12 FE, WBL for young people, Train to Gain and Adult and Community Learning – Learner numbers in England (October 2006; from the Office for National Statistics Annual Population Survey for England (June 2006); and from the National Client Caseload Information System (December 2006). 4 An inspection report on post-16 learning in 20065 found that “the current provision for disabled adults learners is costly and does not provide value for money”. And research in Wales6 has found that disabled learners, in particular those who have physical impairments or health conditions, were at a higher risk of dropping out than other learners. Relatively poor skills are a key part of the disadvantage disabled people face and this relative skills gap may widen further by 2020. The chart below, reproduced from the DRC report, Disability, Skills and Work7 shows projections for the skills mix of disabled people and how this compares with the projection of the UK as a whole – as illustrations of what would happen in the absence of action to change previous trends. It is recognised that children with high aspirations tend to achieve better educational outcomes, i.e. they are more likely to stay on in post-compulsory education and to attain higher qualifications. Yet research found that this did not hold for disabled young people 8. Comparing young people with physical or 5 Greater Expectations: provisions for learners with disabilities. Adult Learning Inspectorate (2006) FE/ WBL Early Leavers Research. Welsh Assembly Government (2006). 7 Disability, Skills and Work Raising our Ambitions, Evans, S. op.cit. 8 Burchardt, T. (2005) “The education and employment of disabled young people. Frustrated ambition”, Joseph Rowntree Foundation 6 5 sensory impairments, and those with mental health problems with their nondisabled peers found very similar aspirations for disabled and non-disabled young people: 62 per cent of disabled 16-year olds wanted to stay on in education (vs. 60 per cent of non-disabled young people); 33 per cent aspired to a professional occupation (vs. 24 per cent for their non-disabled peers); both groups of individuals had similar expectations about the average weekly pay. However, the level of participation and attainment was lower for disabled learners: At age 16/17, only 62 per cent of disabled young people were in full-time education (vs. 71 per cent for their non-disabled peers). By age 18/19, only 50 per cent of disabled young people have their highest qualification above Level 1, while the corresponding figure for non-disabled young people is 72 per cent. Aspirations of disabled young people and their non-disabled peers are very similar, but evidence indicates significant gaps in outcomes pointing to systemic barriers to learning and work that need to be identified and tackled. Careers Information, Advice and Guidance (IAG), in particular provision for young people An EHRC poll9 found that disabled young people are less likely than the population in general to feel emotionally and physically safe at school. In addition, they are less likely to feel able to achieve their potential, to find it easy to learn, to say they have considered dropping out of learning and also say that they are more likely to worry that they will fail. Two in 10 young people (18 per cent or approximately 700,000 young people in England) say they have not had enough information to make choices for their future. This rises to 23 per cent of disabled young people. While the majority of young people aged 14-18 have had a one-to-one interview with a careers or Connexions adviser at school, almost four in 10 (37 per cent) of disabled young people had not. Reasons for this lack of 9 Staying on: making the extra years in education count for all young people. EHRC, (2009). 6 information and inadequate guidance were attributed to professionals not believing that young people could cope with certain choices as a result of viewing disability through a medical model resulting in a ‘damage limitation exercise. This is opposite to a social model approach which looks at ‘disabilities, rights and entitlements’ and identifies the removal of systemic barriers as the way forward in opening up opportunities for disabled people. The poll also found that disabled learners are not receiving enough information about opportunities in work based learning and apprenticeships and information about going onto Further Education is often negative. The EHRC’s Staying On report10 highlighted the pressing need to ensure that young people with learning difficulties and/or disabilities and their families receive better IAG. It is essential for these young people to have fair access to the opportunities enjoyed by their peers, which includes providing IAG to ensure that disabled young people are able to choose from a wide range of educational options. The EHRC believes it is essential to make it clear what the provision of impartial careers education and IAG means in practice. We have some concerns about how the use of the term ‘impartial’ may be interpreted by teachers and others involved in careers education and IAG. It must be made clear that providing impartial careers education does not mean stereotypes cannot be actively challenged by providing information on non-traditional careers and training, and highlighting pay differentials in different sectors/ apprenticeships. This positive promotion of non-traditional learning and work options is crucial in order to break down the entrenched stereotypes holding young people back from making the most of their life chances. Young people must be given un-stereotypical careers education and IAG that supports them to realise their potential. Special educational needs (SEN) co-ordinators in secondary schools and Connexions advisors need to ensure that they encourage positive aspirations, while offering practical support in overcoming barriers for disabled young people. All schools and colleges should include anti- bullying strategies in their equality schemes and action plans. Disabled pupils are more likely to experience bullying and this was identified as a key factor in their disengagement from learning by young people who are NEET. 10 Ibid. 7 Overcoming the lower aspirations that disabled young people have as they move into adulthood is critical if disabled people are to be enabled to take up skills and labour market opportunities. The IAG service must drive equality of expectation for disabled people from employers and equality of aspiration among disabled people. The EHRC has just commissioned new work on equality in careers guidance across equality groups, including disabled young people, with findings expected in Spring 2010. It is worth mentioning the Disability Equality Duty at this point, as it is a requirement that a public authority when carrying out their functions is to have due regard to do the following: promote equality of opportunity between disabled people and other people; eliminate discrimination that is unlawful under the Disability Discrimination Act; eliminate harassment of disabled people that is related to their disability; promote positive attitudes towards disabled people; encourage participation by disabled people in public life; and take steps to meet disabled people’s needs, even if this requires more favourable treatment. Apprenticeships EHRC evidence11 suggests that disabled young people are not given access to work-based learning and apprenticeships and information received on further education options can be negative. An understanding of the social model of disability is crucial here in ensuring disabled young people’s choices are not constrained by beliefs that disabled young people cannot ‘cope’ with certain choices. According to the LSC12, in apprenticeships the success rate for 16-18 year old non-disabled young women is higher (by 9%) at 55%, than for disabled men. In Advanced Apprenticeships non-disabled young men have a 20% higher success rate, at 59%, than disabled young women. Similar success rates are found in those taking apprenticeships who are 19 and over, with 9% difference 11 Ibid. These statistics are taken from ILR/SFR 12 FE, WBL for young people, Train to Gain and Adult and Community Learning – Learner numbers in England (October 2006; from the Office for National Statistics Annual Population Survey for England (June 2006); and from the National Client Caseload Information System (December 2006). 12 8 for non-disabled women vs. disabled men, and 19% difference for nondisabled men compared to disabled women. As is suggested in the DCSF’s Equality Impact Assessment for the Apprenticeships, Skills, Children and Learning Bill, it would be very useful for relevant partners to develop information, advice and guidance for disabled people so that they are aware of apprenticeships and the assistance that is available to them. It would also be appropriate to ensure that apprenticeship providers put in place the necessary reasonable adjustments and support services for disabled people. Employment In 2006 over 50% of disabled people and people with long term health conditions are unemployed, 25% above the national average. Disabled people and people with long-term health conditions have lower employment rates no matter what their qualification level. The chart below, reproduced from the DRC’s Disability, Skills and Work Report13 illustrates how disabled people are disadvantaged at every level of qualification by employment rate, hence disabled people educated to level 3 are less likely to be in employment (at 59%) than non-disabled people with no qualifications (at 61%). 13 Disability, Skills and Work, Raising our Ambition. Evans, S., Op.cit. 9 Disabled people are less likely to work in managerial and professional occupations14. The consequences of a lower income for disabled people can increase the risk of poverty and social exclusion, which can impact on their children’s educational attainment and future life chances15. Only one in ten people with severe learning disabilities and two in ten people with mental health problems had a job in 2006. Employment rates are also lower than the 50 per cent national average for disabled people in some parts of Britain – 47 per cent in Scotland, 45 per cent in the North West region of England, 43 per cent in Wales, 42 per cent in London and just 40 per cent in North East England16. Improving skills acquisition and use: collaboration and partnership between providers Sector Skills Councils (SSCs) need to be encouraged to target low-skilled and under-represented groups, and initiatives such as Train to Gain have the potential to target individuals with protected characteristics as the scheme is focused on those with low skills. The role of new flexible ways of working in translating skills acquisition into use and reward needs to be much higher on the agenda for employers, the Adult Advancement and Careers Service (AACS), SSCs and other skills brokers, and JobCentresPlus. The new right to request time off to train needs to be implemented flexibly to recognise the increased needs of individuals with caring responsibilities or disabilities. This should be linked in with the requirement to make reasonable adjustments for disabled people. A focus on sustainable employment and progression should be seen as a key objective of employment services. Skills should be much more closely integrated into Welfare to Work support, with the basic skills needs of all claimants assessed at the start of their benefit claim. This would enable advisors to tailor their training in basic skills to the individual. Where basic skills needs are a key barrier to finding work, action to improve basic skills should be integrated into the Back to Work Plan. This should be linked to in14 Disability Briefing March 2006. DRC (2006). Narrowing the Gap: the Final Report of the Fabian Commission on Life Chances and Child Poverty. Fabian Society (2006). 16 The Disability Agenda: Ending Poverty and Widening Employment Opportunity. Disability Rights Commission (2007). 15 10 work support for people who do find work, such as Train to Gain. Providers should be rewarded for sustainable employment and progression, not just job entry. The employer must recognise their responsibilities in addressing the numbers stopping working after developing an impairment or health problem, including mental health condition, as this can lead to too few disabled people participating in skills development. The Access to Work Scheme should be developed to better address barriers to workforce development, with a simplification of the process for claiming funds for these in-work benefits. Alongside this, improved information and advice for firms should be made available to enable them to understand the benefits system and the issues and challenges faced by disabled workers. The National Institute for Adult Continuing Education (NIACE) has practical experience of working with people with learning difficulties, and runs a four day course for education providers based on person-centred reviews and is now taking this work forward with pilots, a key findings document, and the development of a national training programme. Necessary elements for successful engagement with disabled people seeking employment include working in partnership with local supported employment agencies, working with supported employment services that are part of local social services department, and incorporating into training key roles of supported employment. The implementation of new Careers Strategy for Young People, Quality, Choice and Aspiration, and the new AACS must be informed by the need to raise expectations, embedding the expectation that people with learning disabilities can work, across delivery of education and skills strategies. NIACE has found that the current supported employment approach is patchy. Education and training providers need to develop strong working partnerships with employers, JobCentresPlus, supported employment agencies and parents/ carers. They stress that there need to be more opportunities for work experience placements in real work settings. These should be part of vocational course, and should be accredited. 11 NIACE recognises the complexity of putting together ‘packages’ of support for people with learning difficulties; however this approach needs to have an adult careers guidance voice at the centre of it. To ensure that information and support for firms deliver sufficient improvements in the employment and skills development opportunities for disabled people may require additional measures, and these could include equality audits, going beyond gender pay gaps. The EHRC would like to see audits of equality of pay, training and other workplace opportunities for all individuals with protected characteristics. Conclusion Some key challenges for improving skills and progression opportunities for disabled people include: increasing the meaningful participation of disabled people in higher and further education; ensuring that disabled people are more actively involved in the design, development, review and delivery of education, skills and work policies that affect them; ensuring that capital funding covers reasonable adjustments and specialist support services to enable access to learning for disabled people; developing information, advice and guidance (IAG) for disabled people, including those with learning difficulties, so that they are fully aware of the full range of learning, career and work opportunities, and of funding and assistance available to them; addressing under-use of skills; and addressing low levels of awareness and understanding of disability issues amongst the general public and amongst employers, employees and providers of skills training. The disability equality duty also needs to be actively considered by public sector organisations when developing IAG, apprenticeships and skills training. The EHRC has just commissioned two new research reviews on the education, skills and employment aspirations, experiences and outcomes of disabled people. We hope that taking a fresh, solution-focused look at evidence, will enable us to make findings and recommendations pointing to new ways of removing barriers to skills and work. The research is due to report in Spring 2010. 12