Management of iatrogenic hepatic encephalopathy

Management of Iatrogenic Hepatic Encephalopathy

PETER FERENCI *

KEY CONCEPTS

Iatrogenic hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is defined by the occurrence of brain dysfunction is a direct consequence of a medical intervention (shunt procedures, drugs) in a previously asymptomatic patient with liver disease.

The incidence of HE varies considerably among patients with cirrhosis with or without any shunt procedure.

In patients treated with TIPS the overall incidence of HE is increased, but the difference disappears when only episodes of overt HE are counted. Spontaneous HE prior to TIPS is the most consistent independent prognostic variable.

After shunt procedures most episodes of HE are short lived and are amenable to simple medical measures and avoidance of precipitants.

In few patients chronic HE may be debilitating and requires closure of the shunt. In some, liver transplantation should be considered.

Post-TIPS HE is a problem that may have been overstated. No a routine prophylactic administration of drugs is justified outside of clinical studies.

DEFINITION

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a syndrome of impaired brain function due to liver failure.

Iatrogenic HE thus describes a part of this syndrome which is precipitated or worsened by medical procedures or treatments. It should be emphasized that this entity has not been used as a separate diagnosis sofar. To define this condition one has to assume that:

1.

a patient with liver disease has normal CNS function before treatment and

2.

that HE is a direct consequence of the medical intervention.

In clinical practice, these requirements are rarely met. Normally an apparently asymptomatic patient with cirrhosis experiences a medical problem, receives therapy to improve it, and develops symptoms of HE thereafter. Thus the causal relation between the medical intervention and the appearance of symptoms is circumstantial and cannot be firmly established. Nevertheless, HE occurs frequently following certain treatments such as portocaval shunt procedures or some drugs - these forms of HE can be considered as iatrogenic and will be discussed in this paper. In a broader sense, the term iatrogenic HE could also be used if a medical therapy causes severe liver disease complicated by HE (ie. drug-induced acute liver failure).

The incidence of HE in cirrhotics varies according to the definitions and diagnostic tests applied. By including cases with minimal (subclinical) HE, HE may be present in about 70% of patients (1). A fairly accurate estimate of the incidence of clinical HE can be derived from controlled studies for treatment of portal hypertension. HE occurred in 0 - 48% of medically treated patients (2), in 30 to 53% of patients with end to side portocaval shunts, and in 24 -

39% of patients with distal spleno-renal shunts (3,4,5,6). The variations of the incidence of

HE can be best explained by different criteria used to diagnose HE:

* Department of Internal Medicine IV, Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Währinger Gürtel 18-20, A-1090 Wien, Austria

Fax: +43 1 40400 4735, E-mail: peter.ferenci@akh-wien.ac.at

83

The diagnosis of overt HE is simple and straightforward. For clinical studies the mental state is graded HE in stages I to IV based on changes in consciousness, intellectual function and behavior (7). It does not include neurological changes or asterixis. The Glasgow Coma scale is useful in stages III and IV.

In contrast, diagnosis of mild or minimal HE is difficult. Several psychometric tests are used to quantitate mild stages of HE (1,8,9). Psychometric testing is more sensitive in the detection

of minor deficits of mental function than clinical assessment or EEG (8). However, they are

cumbersome and when applied repeatedly the reliability of most of them is adversely affected by the learning effect. Only few are useful in the daily routine. Psychometric tests overdiagnose minimal HE because scores are usually not corrected for age (10,11). The “PSE-

index” (2), which combines clinical, psychometric, and laboratory data, has several

shortcomings (12). It does not discriminate between overt, mild or minimal HE and was not validated prospectively. Electrophysiologic tests may be useful to quantify overt HE in studies. In conventional EEG tracings the degree of abnormality can be graded semiquantitatively. Computer assisted techniques can quantitate variables such as the mean dominant EEG frequency or the power of a particular EEG rhythm. Evoked or event related responses, like the P300 peak after auditory stimuli are sensitive to detect subtle changes of brain function and can be used for diagnosis of minimal HE (13).

INCIDENCE OF IATROGENIC HEPATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY:

The incidence of minimal HE varies considerably among patients with cirrhosis (see table 1).

Most frequently, procedures that create a wide shunt between the portal- and systemic venous circulation to decrease portal pressure may increase the incidence of HE. But also some drugs may affect brain function in a manner undistinguishable from HE.

Shunt-Surgery and TIPS

Although it is conventional knowledge that any shunt procedure may increase the risk to develop HE, the published data not always support this assumption. Several factors may explain such discrepant findings and include patient selection (assessment of pretreatment brain dysfunction), criteria and tests for diagnosis of HE, the length and frequency of the follow up, as well as the treatment of control and study groups. The results on the frequency of HE in various prospective, randomized trials are listed in table 2. Some of the data were quite surprising. For example the incidence of HE in patients treated with endoscopic sclerotherapy was 3 fold higher in studies using TIPS than in those with distal splenorenal shunt. The rate of HE was not different when distal splenorenal shunt was directly compared with end-to-side portacaval shunt, although all textbooks state that distal splenorenal shunt has a much lower incidence of HE.

In patients treated with TIPS the overall incidence of HE is increased, but this difference disappears when only episodes of overt HE are counted. Spontaneous HE prior to TIPS is the most consistent independent prognostic variable predicting therefore be a relative contraindication for TIPS its development and should

Drugs

Although drug-induced HE is always discussed, actual data are quite scarce. The best evidence for drug-induced HE is documented for benzodiazepines. The role of benzodiazepines for the pathogenesis of HE is still under discussion (for review: 12). Rats with liver failure are more sensitive to the sedative effects of benzodiazepines than normal rats (14). Similarly, in humans an increased sensitivity of patients with cirrhosis to benzodiazepines was clearly documented (15). After an ordinary sedative dose (0.25 mg) the apparent oral clearance of unbound triazolam was lower in cirrhotics than in controls.

84

Clearances correlated with severity of liver disease. At a time when plasma concentrations of unbound triazolam were the same as in controls (2.25 hr after dosing), flicker sensitivity at 5

Hz and the digit symbol substitution test were impaired in cirrhotics .

In patients dying with

HE t exogenous administered benzodiazepines was accounted for the presence of benzodiazepines in brain tissue (16).

Other drugs which may precipitate or worsen HE are loop diuretics (17,18), propranolol

(19,20) and ketanserin (21).

TREATMENT OF IATROGENIC HEPATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY

Drug-Induced Hepatic Encephalopathy

The treatment of choice in benzodiazepine-induced HE is the use of flumazenil (12). If tranquilizers are needed in patients with cirrhosis potential side effects can be reduced by using lower doses. For other drugs usually a supportive therapy is sufficient to allow the excretion and /or metabolic inactivation of the drug to take place.

HE AFTER PC-SHUNT PROCEDURES

Overt Hepatic Encephalopathy

After shunt procedure, most episodes of HE are short lived, do not require admission to hospital, and are amenable to simple medical measures such as lactulose and avoidance of precipitants (22,23). New onset HE is clustered around the first month after TIPS insertion and improvement of neurological status was observed in a significant number of patients during follow up.

Chronic spontaneous encephalopathy develops in about 10%. In addition of standard measures, protein restriction in combination with supplementation of the diet with branched chain amino acids may ameliorate the condition of the patients. Beyond that, drug treatment may be helpful in selected cases. Bromocriptin or oral flumazenil were effective in single cases (24) and cannot be generally recommended. If the condition is sufficiently debilitating it requires closure of the shunt. This can be done using reducing stents, LGV filters or coils, but when these measures fail, suggesting that deteriorating liver function encephalopathy, liver transplantation should be considered. is the cause of the

Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy

Although the number of patients with minimal HE is large, good clinical studies are rare.

Even among experts, there is no agreement how to define minimal HE or whether minimal

HE exists at all. Efficacy of treatment is judged by the improvement of psychometric tests or of electrophysiologic measurements. The impact of these parameters and the benefit of their improvement for the patients is uncertain. Substances that modify psychometric tests in prospective studies include lactulose (25,26), ornithin-aspartate (27) and oral BCAA (28,29)

.

A need for treatment of minimal HE is not established and should only be used in controlled clinical trials. There is no single study addressing reasonable treatment endpoints such as improvement in quality of life . Good clinical studies are badly needed.

Prevention of HE in patients with PC-shunt procedures

Post-TIPS HE is a problem that may have been overstated so far. Not a single study has been published sofar to justify a routine prophylactic administration of drugs to decrease the likelihood of the occurrence of HE after the procedure. Certainly the best prophylaxis of HE is to select patients carefully for TIPS placement. In patients with a high-risk profile (Child class

C, pretreatment HE, age >65 years) all other treatment options should be explored and TIPS should only used as last resort.

85

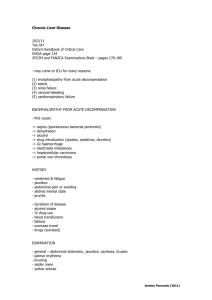

Table 1: Frequency of abnormal test results (in %) in patients with cirrhosis without overt signs of hepatic encephalopathy (only studies using age adjusted normal values listed).

Autor (Ref) N NCT Symbol digit other spectral

EEG evoked responses

130 17

Quero (11) 137 7

Groeneweg (30) 179 9

Yang (31) 61 31

Amodio (32)

Amodio (33)

100 19

94 21

5

3

Posner-test: 17

Choice 2: 20

Scan: 23

17

19

40

47.5

NCT: Number connection test A

Table 2: Frequency of HE in patients with cirrhosis and shunt procedures (only in prospective controlled trials)

Surgery Endoscopy TIPS Medical OR treatment

DSRS vs. ET (34) Chronic HE:16

Acute HE: 7

PC-Shunt vs.

Control (35)

Prophylactic: 45

Therapeutic: 35

Chronic HE:9

Acute HE: 6

Prophylactic: 28

Therapeutic: 7

1.9 (1.1-3.6)

NS

2.0 (1.2-3.1)

4.9 (2.1-11.3)

PC-Shunt vs. DSRS

ET vs.TIPS (36) 19 34

1.3 (0.8-2.2)

0.43 (0.3-0.6)

DSRS= distal splenorenal shunt; ET: endoscopic therapy; OR= Odd´s ratio (95% confidence interval)

REFERENCES

1 Schomerus H, Hamster W, Blunck H, Reinhard U, Mayer K, Dölle W. Latent portosystemic encephalopathy I. Nature of cerebral functional defects and fitness to drive. Dig Dis Sci

1981;26:622-630

2 Conn HO, Leevy CM, Vlahcevic ZR, Rodgers JB, Maddrey WC, Seeff L, et al. Comparison of lactulose and neomycin in the treatment of chronic portal-systemic encephalopathy.

Gastroenterology 1977;72:573-83

3 Rikkers LF, Rudman D, Galambos JT et al. A randomized controlled trial of the distal splenorenal shunt. Ann Surg 1978;188:271-282

4 Resnick RH, Iber FL, Isihara AM et al. A controlled study of the therapeutic portocaval shunt. Gastroenterology 1974;67:843-857

5 Reynolds TB, Donovan AJ, Mikkelsen WP et al. Results of a 12-year randomized trial of portocaval shunt in patients with alcoholic liver disease and bleeding varices.

Gastroenterology 1981; 80:1005-1014

86

6 Langer B, Taylor BR, Mackenzie DR et al. Further report of a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing distal splenorenal shunt with End-to-Side portocaval shunt. An analysis of encephalopathy, survival, and quality of life. Gastroenterology 1985;88:424-432

7 Conn HO, Lieberthal MM. The hepatic coma syndromes and lactulose. Williams & Wilkins,

Baltimore 1979

8 Rikkers L, Jenko P, Rudman D, Freides D. Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy: Detection, prevalence and relationship to nitrogen metabolism. Gastroenterology 1978;75:462-469

9 Conn HO. Trailmaking and number connection tests in the assessment of mental state in portal systemic encephalopathy. Am JDig Dis 1977;22:541-550

10 Weissenborn K, Ruckert N, Hecker H, Manns MP, The number connection tests A and B: interindividual variability and use for the assessment of early hepatic encephalopathy. J

Hepatol 1998;28:646-653

11 Quero JC, Hartmann IJ, Meulstee J, Hop WC, Schalm SW. The diagnosis of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis using neuropsychological tests and automated electroencephalogram analysis. Hepatology 1996;24:556-560

12 Ferenci P. Hepatic encephalopathy: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Pathogenesis.

Treatment. In: UpToDate [CD-ROM], Rose, BD (Ed), UpToDate, Wellesley 1999.

13 Kullmann F, Hollerbach S, Holstege A, Schölmerich J.: Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy: the diagnostic value of evoked potentials. J Hepatol 1995;22:101-110

14 Püspök A, Herneth A, Steindl P, Ferenci P.Hepatic encephalopathy in rats with thioacetamide induced acute liver failure is not mediated by endogenous benzodiazepines.

Gastroenterology 1993; 105:851-857

15 Baktir G, Fisch HU, Karlaganis G et al. Mechanism of the excessive sedative response of cirrhotics to benzodiazepines: Model experiments with triazolam. Hepatology 1987;7:629-

638

16 Perney P, Butterworth RF, Mousseau DD, Lavoie J, Fabbro-Peray P, Blanc F, Layrargues

GP Plasma and CSF benzodiazepine receptor ligand concentrations in cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy: relationship to severity of encephalopathy and to pharmaceutical benzodiazepine intake. Metab Brain Dis 1998;13:201-10

17 Sherlock S, Senewiratne B, Scott A, Walker JG .Complications of diuretic therapy in hepatic cirrhosis. Lancet 1966;i:1049-52

18 Naranjo CA, Pontigo E, Valdenegro C, Gonzalez G, Ruiz I, Busto U. Furosemide-induced adverse reactions in cirrhosis of the liver.

Clin Pharmacol Ther 1979;25:154-60

19 Reding P Risk of hepatic encephalopathy in patients taking propranolol for portal hypertension. Lancet 1982;ii:550

20 Snady H, Lieber CS. Venous, arterial, and arterialized-venous blood ammonia levels and their relationship to hepatic encephalopathy after propranolol. Am J Gastroenterol

1988;83:249-55

21 Vorobioff J, Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann R, Aceves G, Picabea E, Villavicencio R,

Hernandez-Ortiz J. Long-term hemodynamic effects of ketanserin, a 5-hydroxy-tryptamine blocker, in portal hypertensive patients. Hepatology 1989;9:88-91

22 Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, et al. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study.

Hepatology 1994;20:46-55

23 Somberg KA, Riegler JL, LaBerge JM, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: incidence and risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol

1995;90:549-555

24 Ferenci P, Grimm G, Meryn S. Gangl A. Successful longterm treatment of portal systemic encephalopathy by the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil. Gastroenterology

1989;96:240-243

87

25 Watanabe A, Sakai T, Sato S, Imai F, Ohto M, Arakawa Y, et al. Clinical efficacy of lactulose in cirrhotic patients with and without subclinical hepatic encephalopathy.

Hepatology 1997;26:1410-4

26 Horsmans Y, Solbreux PM, Daenens C, Desager JP, Geubel AP. Lactulose improves psychometric testing in cirrhotic patients with subclinical encephalopathy. Aliment

Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:165-70

27 Stauch S, Kircheis G, Adler G, Beckh K, Ditschuneit H, Görtelmeyer R, et al: Oral Lornithine-L-aspartate therapy of chronic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a placebocontrolled double-blind study. J Hepatol 1998; 28: 856-64

28 Egberts EH, Schomerus H, Hamster W, Jurgens P. Branched chain amino acids in the treatment of latent portosystemic encephalopathy. A double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Gastroenterology 1985;88:887-95

29 Plauth M, Egberts EH, Hamster W, Torok M, Müller PH, Brand O, Fürst P, Dölle W.

Long-term treatment of latent portosystemic encephalopathy with branched-chain amino acids. A double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. J Hepatol 1993;17:308-14

30 Groeneweg M, Quero JC, De Bruijn I, Hartmann IJC, Essink M, Hop WCJ, Schalm SW.

Subclinical hepatic encephalopathy impairs daily functioning.Hepatology 1998;28:45-49

31 Yang SS, Wu CH, Chiang TR, Chen DS. Somatosensory evoked potentials in subclinical portosystemic encephalopathy: A comparison with psychometric tests. Hepatology 1998;27:

357-361

32 Amodio P, Marchetti P, Del Piccolo F, Campo G, Rizzo C, Iemmolo RM, et al. Visual attention in cirrhotic patients: a study on covert visual attention orienting. Hepatology

1998;27:1517-23

33 Amodio P, Del Piccolo F, Marchetti P, Angeli P, Iemmolo R, Caregaro L, et al. Clinical features and survival of cirrhotic patients with subclinical cognitive alterations detected by the number connection test and computerized psychometric tests. Hepatology

1999;29:1662-7

34 Spina GP, Henderson JM, Rikkers LF, Teres J, Burroughs AK, Conn HO, Pagliaro L et al.:

Distal splenorenal shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy in the prevention of veariceal rebleeding. A metaanalysis of 4 randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol 1992;16:338-345

35 D´Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: A meta-analytic review. Hepatology 1995:22:332-54

36 Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, et al . Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: A metaanalysis.

Hepatology 1999;30:612-622

88