Dafydd ap Gwilym, poet and musician

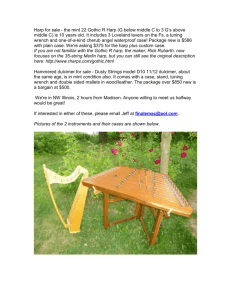

advertisement