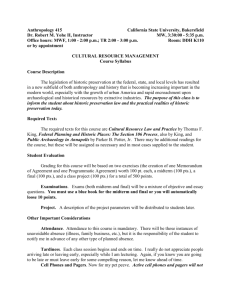

Historic Preservation: theory and practice

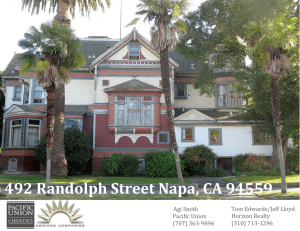

advertisement