Garbage men and Archaeologists: What can trash tell us about people

advertisement

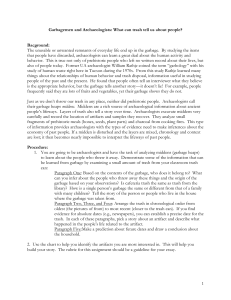

Garbagemen and Archaeologists: What can trash tell us about people? Jessica Munson Objectives: In studying archaeological concepts, students will analyze garbage from a variety of different contexts to: 1) demonstrate competence in applying the concepts of culture, context, classification, observation and inference, and chronology to scientific inquiry; and 2) explain how their study of garbage relates to methods in archaeology. Standards: (this is an estimate and does not reflect AZ state standards) Subjects – Science, Communication Skills – classification, observation, application, synthesis, inference, evaluation Strategies – game, discussion, group cooperation Background: The unusable or unwanted remnants of everyday life end up in the garbage. By studying the items that people have discarded, archaeologists can learn a great deal about the human activity and behavior. This is true not only of prehistoric people who left no written record about their lives, but also of people today. Former UA archaeologist William Rathje coined the term “garbology” with his study of human waste right here in Tucson during the 1970s. From this study Rathje learned many things about the relationships of human behavior and trash disposal, information useful in studying people of the past and the present. He found that people often tell an interviewer what they believe is the appropriate behavior, but the garbage tells another story—it doesn’t lie! For example, people frequently said they ate lots of fruits and vegetables, yet their garbage shows they do not. Just as we don’t throw our trash in any place, neither did prehistoric people. Archaeologists call their garbage heaps middens. Middens are a rich source of archaeological information about ancient people’s lifeways. Layers of trash also tell a story over time. Archaeologists excavate middens very carefully and record the location of artifacts and samples they recover. They analyze small fragments of prehistoric meals (bones, seeds, plant parts) and charcoal from cooking fires. This type of information provides archaeologists with the types of evidence need to make inferences about the economy of past people. If a midden is disturbed and the layers are mixed, chronology and context are lost; it then becomes nearly impossible to interpret the lifeways of past people. Vandals looking for artifacts dig in middens, and they destroy irreplaceable information about the past. Everyone can help by not digging archaeological sites or collecting artifacts and by refusing to buy artifacts from people who do. Prep Time: 1 – 5 days before: o gather trash bag samples from different contexts (e.g., classroom, cafeteria, library) o Refer to the Garbage Content Ideas teacher aide Print Handout: “Garbage Chart worksheet” 1 day before – vocabulary exercise to make sure students are familiar with terms used in lesson 1 Materials: 1 trash bag sample for each group of 3-4 students in the classroom. The trash bag could be about the size of a grocery bag and contain items appropriate for specific contexts. For example, a trash bag from the cafeteria might contain empty milk containers, apple cores, plastic sandwich bags, etc. while a trash bag from the library might contain an old newspaper, computer printer paper, a broken pencil, and wads of chewing gum. The objective is to find or “create” trash bag samples that are unique to specific contexts and that may contain some type of chronological information (e.g., date on newspaper). Disposable gloves (optional, depending on type of trash) 1 activity worksheet for each group Vocabulary: Artifact – any object made, modified, or used by humans; usually refers to a portable item Chronology – an arrangement of events or periods in the order in which they occurred Classification – a systematic arrangement in groups or categories according to established criteria Context – the relationship artifacts have to one another and the situation in which they were found Culture – the set of learned beliefs, values, styles, and behaviors generally shared by members of a society or group Data – information, especially information organized for analysis Evidence – data that are used to support a conclusion Hypothesis – a proposed explanation or interpretation that can be tested by further investigation Inference – a conclusion derived from observations Midden – an area used for trash disposal; a deposit of refuse Observation – the act of recognizing or noting a fact or occurrence; the record obtained by such an act Activity: Setting the Stage: 1. Review the vocabulary terms used in this exercise the day before the lesson. Make sure the students are familiar with the word “midden” in particular. 2. Review some of the general background information provided above as a means to introduce the lesson. Make sure to mention the Rathje “garbology” term/project. 3. Get the students thinking about their own garbage by posing the question: What do you think your family’s garbage could tell about you? (e.g., family size, income, preferred foods, and activities) Procedure: 4. Explain to the students that they are going to be archaeologists and have the task of analyzing middens (garbage heaps) to learn about the people who threw it away. Demonstrate some of the information that can be learned from garbage by examining a small amount of trash from your classroom trash can: a. Based on the contents of the garbage, who does it belong to? Could the garbage be mistaken for another group? Is the garbage in your classroom the same or different from classroom garbage in China? From 100 years ago? b. What can you infer about the people who threw away these things and the origin of the garbage based on your observations? Is cafeteria trash the same as trash from 2 the library? How is a single person’s garbage the same or different from that of a family with many children? c. Arrange the trash in chronological order, starting with the most recent deposit. On the bottom is the oldest trash. If you find evidence for absolute dates (e.g., newspapers), you can establish a precise date for the trash. d. Sort the trash into piles based upon some type of similarity. This is a classification, perhaps including categories such as paper, food containers, office supplies, etc. e. Discuss the context of the trash. f. Construct a scientific inquiry. An example is: “Was the person who made this trash a young or old student?” The hypothesis could be: “If there is are many papers with cursive writing in the trash, the then trash probably didn’t come from very young children and was instead trash from older children.” Classify the trash into two categories: papers with and papers without cursive writing. Accept or reject your hypothesis. 5. (20 minutes) Divide the class into groups of 3 to 4 students and give each group a bag of trash (and disposable gloves if necessary). The group should analyze the trash using the activity worksheet. 6. Have a spokesperson from each group present a summary of their findings to the class. Closure: 7. When students propose an inference about the people who generated the garbage, ask them, lead a discussion by posing the following questions: a. What would the activity you are proposing (hypothesis) look like archaeologically? What artifacts would you expect to find if your hypothesis is correct? b. Does your study of your garbage tell you everything about American society? Why or why not? c. Do the contents in your garbage can change throughout the year? As a result of special occasions like birthdays or company for dinner? What mistakes might an archaeologist make about your family if he/she studied only the garbage from your birthday party? (You can also use a festival like Christmas or Hannakuh instead of birthday trash.) d. How would the results of your study be different if we had mixed your individual garbage bags all together into one heap? Evaluation: The student worksheets can be assessed. Class participation in discussion can be assessed. 3