The Other Boleyn Girl

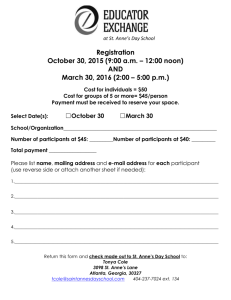

advertisement

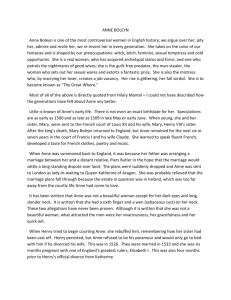

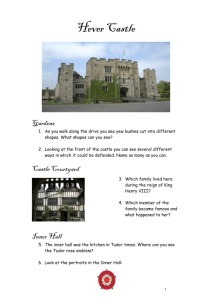

The Other Boleyn Girl By Alison Plowden Mary Boleyn enjoyed a royal fling with Henry VIII before her younger sister Anne moved into the limelight. Alison Plowden reveals the little-known story of a fascinating figure. Family background The rise of the family of Mary Boleyn, and of her sister Anne, future wife of Henry VIII, followed a classic pattern. The family came originally from Sall in Norfolk, and early in the l5th century Geoffrey Boleyn, younger son of a tenant farmer, had come up to London to seek his fortune. He was admitted to the freedom of the city in the art of mercer, married an aristocratic wife and rose to become Lord Mayor. Before his death in 1463 he had acquired Blickling Hall in Norfolk from Sir John Fastolf, and the manor and castle of Hever from the Cobhams of Kent. Geoffrey's son, William, had no need to concern himself with trade. He was created a Knight of the Bath by Richard III and married into the noble Anglo-Irish family of Butler, his wife being the daughter and co-heiress of the Seventh Earl of Ormonde. The Boleyns were now well on their way up the social ladder and William's second son, Thomas, came to court to make his way in the royal service, one of the new men for the new Tudor dynasty. He, too, made a useful marriage - to Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of the second Duke of Norfolk - a marriage that brought him three surviving children, George, Mary and Anne. Early years There has always been a certain amount of confusion between the Boleyn sisters at this period of their lives, and doubt over their dates of birth. Suggested birth dates for Anne vary between 150l and 1507, and although it is most likely that Mary was the elder of the two, there may have been no more than twelve months between them. All we really know for sure is that both girls spent some part of their early years abroad. By 1512 their father was undertaking diplomatic missions to Europe and used his official connections to get the extra advantage of a Continental 'finish' for his daughters. '... in 1514 Mary Boleyn went over to France in the train of Henry VIII's sister (Mary) when the latter was briefly married to old Louis XII.' One of them, now generally thought to be Anne, lived for a time in the household of Margaret, Archduchess of Austria and Regent of the Netherlands, and in 1514 Mary Boleyn went over to France in the train of Henry VIII's sister (Mary) when the latter was briefly married to old Louis XII. Again information is scanty, but it is known that Anne presently joined Mary at the French court, entering the service of Queen Claude, wife of the new king Francois I. Mary returned to England before Anne, though we don't know exactly when, and brought with her a colourful reputation for wanton behaviour. Francois I, himself a notorious womaniser, described her ungallantly as his 'English mare' and another French commentator was later to refer to her in even more outspoken terms. In spite of this, her father apparently experienced no difficulty in finding her a place at the English court, as one of Queen Catherine of Aragon's maids of honour. Life at court Mary Boleyn became Henry VIII's mistress, probably for about two years from 1519, for in February 152l she was married off to William Carey, a gentleman of the king's Privy Chamber. This must have come as a considerable disappointment to her ambitious family, for while there was little real social stigma attached to having been the King's mistress it undoubtedly affected a girl's matrimonial prospects, and she had a right to expect some royal compensation. 'As a godly Protestant prince, with all the serious and devout nature of the real Charles, he would have been assured of considerable support in Britain.' But Henry was notoriously stingy towards his extra-marital partners - even Elizabeth Blount, who had given him a bastard son, achieved no more than a respectable marriage - and although William Carey was one of the king's close companions, which might give him useful opportunities for further advancement, he was otherwise of no particular account. Carey was a younger son without land or fortune, and remained dependent on casual royal bounty in the shape of keeperships, stewardships and the occasional grant of a manor. Thomas Boleyn may well have reflected on how much better these things were managed in France, where the maitresse en titre was a recognised public figure, wielding influence and patronage. There were two surviving children of the Carey marriage, Catherine, born in l524, and Henry, in 1526. The rumour that Henry was the king's son appears to have been founded on no more than the recollection of John Hales, vicar of Isleworth, who some ten years after the child was born remarked that a Brigettine monk from Sion had once showed him 'young Master Carey' saying he was the king's bastard. But by the time of young Master Carey's birth, Mary's royal fling was well over and the king was already becoming infatuated with her younger sister. Anne had returned to England at the end of 1521, but the marriage planned for her with one of her Irish cousins had fallen through and her own unauthorised romance with Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland's heir, had been blighted by Cardinal Wolsey, so that in the mid-1520s she was still unspoken for. As ambitious as her father, and more strong-willed and intelligent than Mary, though apparently not so good-looking, Anne had no intention of becoming another royal mistress. With her sister's example before her, she knew it would lead to nothing more than a second-rate and perhaps unhappy marriage, and she meant to do better than that. William Carey died of the sweating sickness in the summer of 1528, but as far as we know Mary remained at court throughout Anne's determined, skilful, six-year-long campaign to win the greatest prize of all - marriage to the king. One can imagine Mary playing a supportive sisterly role, and perhaps drawing on her own experience to give advice on how best to please the king, without allowing him to proceed to the 'ultimate conjunction'. There are occasional references to Mary in Henry's private letters, and in November 1530 he gave Anne £20 to redeem a jewel from her sister, probably given in payment for a gambling debt. By this time Anne was within sight of her goal. In 1531 the king finally separated from Queen Catherine, his faithful wife for 20 years, and in October 1532, the battle for his divorce all but won, he and Anne paid a state visit to France. Mary was among the 30 ladies who accompanied them. Later years From her place in the background Mary would have been able to watch her sister's triumph, as Anne, by this time visibly pregnant, was crowned queen in the summer of 1533. The Boleyns were now riding high. Thomas Boleyn had been created Earl of Wiltshire, brother George was Viscount Rochford - but there was nothing for Mary and, surprisingly, no attempt seems to have been made to find her another husband. She was probably still only in her late 20s and, considering her family's present ascendancy, surely a very desirable match; but nothing happened until 1534, when Mary took matters into her own hands by falling in love and making a runaway marriage. Her new husband was one William Stafford, another member of the royal entourage and another younger son without money or land. The family was furious. 'Her father cut off her allowance and her sister banished her from court ...' Her father cut off her allowance and her sister banished her from court, so that Mary was obliged to appeal for help to Master Secretary Thomas Cromwell. She admitted that she might have chosen 'a greater man of birth and a higher', but never one that should have loved her so well, nor a more honest man. And she went on, 'I had rather beg my bread with him than to be the greatest queen in Christendom. And I believe verily ... he would not forsake me to be a king.' She begged Cromwell to intercede for her with her father and mother, her uncle Norfolk and her brother. 'I dare not write to them, they are so cruel against us.' But the Staffords were not forgiven, and remained outcasts living in rustic retirement at Rochford in Essex. This turned out to be just as well, for they were thus able to escape any involvement in the witch-hunt surrounding the eventual disgrace, trial and execution of both Anne and her brother George, as well as the five other young men in their circle. After her parents' death Mary inherited the Boleyn properties in Essex, and herself lived on until l543, long enough to watch as her young cousin Catherine Howard was exploited and ultimately sacrificed to family ambition. Afterwards Ironically it was Mary, the feckless, unregarded member of the family, who gave the Boleyns their posterity, for her children were to prosper in the reign of Anne's daughter, Elizabeth I, who always showed special favour towards her mother's kin. Catherine Carey married Sir Francis Knollys, a distinguished pillar of the Elizabethan establishment, and became one of the queen's closest friends. Henry Carey was raised to the peerage as Baron Hunsdon and followed a military career. He played a leading part in suppressing the Northern Rising of 1569, and was rewarded with a personal note of thanks from his sovereign lady, signed 'Your loving kinswoman, Elizabeth R'. 'Ironically it was Mary, the feckless, unregarded member of the family, who gave the Boleyns their posterity ...' The Boleyn/Carey/Tudor connection continued on to the end of the century. Catherine's daughter Lettice was the mother of Elizabeth's favourite, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, and it was Mary's grandson, Robert Carey, who was with the queen at Richmond Palace in March 1603 and left a moving account of her last illness and death. It was Robert, too, who rode from Richmond to Edinburgh, accomplishing the journey in a record three days, to tell James of Scotland that he was king of England at last. Find out more The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Antonia Fraser (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1992) The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn by RM Warnicke (Cambridge University Press, l989) Tudor Women - Queens and Commoners by Alison Plowden (Sutton Publishing, 2002) Anne Boleyn by Hester Chapman (Jonathan Cape, 1974) Anne Boleyn by EW Ives (Oxford University Press, 1986) About the author Alison Plowden worked in the BBC Radio Drama department as a script editor before leaving to work as a full-time writer. She specialises in the Tudor and Stuart periods and has had numerous books published including The Young Elizabeth; Elizabeth Regina; The House of Tudor; Two Queens in One Isle; The Stuart Princesses; Women All On Fire: The Women of the English Civil War and Henrietta Maria: Charles I's Indomitable Queen.