English version - Convention on Biological Diversity

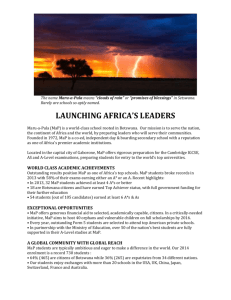

advertisement