Bryan Rome

advertisement

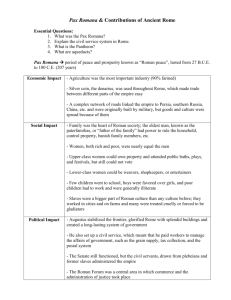

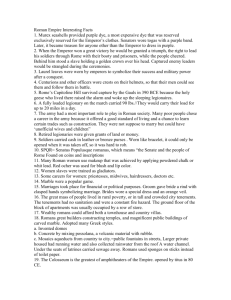

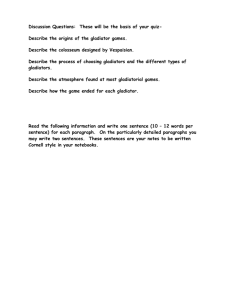

Student 1 Student Student 4 September 2006 Writing 50 Prof. Christopher Dean Historical Perspectives on Gladiatorial Combat Liber Primus: Prefatio With the rebirth in fascination with classical culture, specifically centered around gladiatorial combat, there is a common sentiment shared amongst most that the sport is appalling, gory, and downright atrocious. Many today wonder how so much of the populous of Rome was so blindly mesmerized this brutal act of savagery. Little to their knowledge, the debate over the humanity of the games is far from modern. Many classical scholars including Seneca, Tacitus, and Juvenal shared a common disdain for this form of entertainment; even Cicero himself spoke out against the barbaric phenomenon that had swept the Roman people up by storm. Just as many do now, likely due to a rise in the average educational level or a reversal of cultural morals, there was a specific body of people who held disdain for such a vicious sport. Whilst these great writers and orators, themselves marvelous philosophers, being well educated men of virtue, spoke out against the games, little was done to quell this storm. In fact, quite the opposite took place as the Roman government spent an immeasurable fortune on these games to assure them a satisfied populace. Ter munus gladiatorium dedi meo nomine et quinquiens filiorum meorum aut nepotum nomine, quibus muneribus depugnaverunt hominum circiter decem millia. --Three times I dedicated shows of gladiators to my name and five times under my sons’ and grandsons’ names; in these shows about ten thousand men fought. (Agustus) Even the great Caesar Augustus, Rome’s first emperor, while he may or may not condone the games himself, still furnished spectacles of what the intellectuals 1 Student 2 would call sheer brutality for the people of Rome, demonstrating that while there was opposition from the intellectuals, there was overwhelming support for the games. Furthermore, despite a lack of much written evidence, signs of the support from the masses is quite unmistakable in graffiti and mere logical extrapolation Had there not been such a strong backing, it would have been an unthinkable waste of money on the part of the government to continue such endeavors. This pattern is a rather common theme in Latin literature from the Roman imperial era. It is rather obvious with research that there was an unusual correlation between the education level and social status of a man and his support for gladiatorial combat. It tended to be that the intellectuals held disdain for bloodsport, while the plebs, the commoners, took a fancy to it, enjoying of one man spilling another’s blood on the sands of the Flavian Amphitheater. Liber Secundus: Historia Before understanding the fascination the Roman people held for gladiatorial combat, one must understand that the history of Rome is entrenched deeply in violence and in war. Much unlike contemporary America’s roots in rebellion only for the common good, Rome was founded on the ideas of conquest and expansion. According to Virgil, as he wrote in The Aeneid, Rome was founded by outcasts of the Trojan War, who came to the shores of Italy after facing harsh obstacles and the wrath of Juno1. The hero of this story, Aeneas, leads his men to the future site of Rome, where he met the native Latins. A great battle ensued and the future Romans emerged victorious. While the details of Virgil’s account are, in all likelihood, far from accurate, the theme remains: the roots of the Roman people are in war. What is known however, is that Roman history continued for centuries in the same image, that of conquering, expanding, warring with neighbors, building the strongest empire the world had seen to date. Controlled by the Etruscans, who had much contact with the more civilized Greeks, for much of its early history, Rome began as a 1 Juno was the Roman goddess, equated to the Greek goddess Hera, of marriage. According to Virgil, Juno was enraged when the Trojan prince Paris gave a golden apple, resembling his pick of the most beautiful goddess, not to Juno, but to Aphrodite. Furthermore, she had prior knowledge that the race of Romans that was to come from the Trojans, who she had come to hate, was to annihilate her favorite city, Carthage, in later years. 2 Student 3 kingdom, with a monarchy that began around 753 BCE, much in the fashion of other city-states in the era. Around 509 BCE, when the monarchy collapsed and a republic was instated, Rome won its independence from the Etruscans, beginning its campaign to surpass them as the dominant nation in Italy, and soon, the world. Many of the surrounding cities fell to the mighty Romans, beginning with the Sabines1 and ending with the stabilization of Rome as the power in Northern Italy by the beginning of 3rd Century BCE. Soon following the dominance of Rome over its surrounding states, this fledgling nation was faced with more war as the Guals invaded far from the north. These warriors, led by Brennus, were defeated by the Romans soon after. Before long, much of the rest of Italy and even Greece was to fall to Roman dominance. Following the conclusion of the Punic Wars in 146 BCE, Rome sacked its rival of Carthage in Northern Africa. The “Carthaginian Peace” to follow was just as brutal as the wars that preceded it. The cycle of war went on well into the next millennium as Rome evolved into an empire and conquered much of the known world. By the height of its power, the borders of Rome stretched from Britain to Africa, from Spain almost into India. With a history this bloody, it is apparent why many Romans loved bloodsport to such an extent. Being brought up on a diet of war, many commoners had come to accept it as a natural way of life. However gladiatorial combat wasn’t originally intended for the commoner. The beginnings of gladiatorial contest lied in funerary custom. Following a funeral, the rich would put on shows of combat to honor the dead. With the Roman lust for war and battle, these shows caught on and slowly evolved to what we know them as today. In the height of their popularity, under the Caesars, gladiators were appointed with the best medical care and lodgings available for slaves so they could go on to fight another day, to keep entertaining the crowds. Magnificent stadiums were built to house the shows. The most marvelous of these, known today as the Coliseum, seated 50,000 spectators, longing to see the athletes, to see the wild animal hunts, but mostly to see the gladiators. 1 In the early years of Rome, under its third king, myth dictates that many Roman men found themselves wives when they raped and took many Sabine women back to the city. After the collapse of the Roman monarchy, the dissolution of the Roman kingdom in 509 BCE, and the formation of the republic, Rome gained support from surrounding cities and defeated the invading Sabines in war in 493 BCE. Thus began Rome’s dominance over Italian cities. 3 Student 4 The life of the gladiator was a far cry from the easy life of the wealthy. The gladiator had as few rights as a common slave, whilst being revered by the populace. However, despite their pitiful social status, they were seen as celebrities, and as such their survival was ensured by proper medical care and amenities. Yet, as slaves they were expected to obey the words of their masters: … in verba Eumolpi sacramentum iuravimus: uri, vinciri, verberari ferroque necari, et quicquid aliud Eumolpus iussisset. Tanquam legitimi gladiatores domino corpora animasque religiosissime addicimus… --… in words dictated by Eumolpus we swore an oath, to endure to endure branding, flogging, or death by steel, and whatever else Eumolpus commands. Like legitimate gladiators we pledged ourselves religiously to our master, body and soul…(Petronius) Despite the Satyricon being nothing more than a work of fiction, Petronius manages to embody the oath of the gladiator, explaining how “religiously” they must pledge themselves to their master. The life of a gladiator was not full of glory and freedom. It, contrary to the popular view of the time, was full of hardship and fear of death. Only the precious few would go on to regain their freedom. These are the men that would raise such excitement amongst the crowds. Liber Tertius: Disputatio On the whole, the Romans took quite a fancy to and much entertainment from gladiatorial combat. The concepts of violence were so deeply engrained in the psyche of the Roman citizen, it was to be inevitable that this form of entertainment would be so successful. By the height of the empire, the games had also reached their height; massive amphitheaters were built across the empire to feed the peoples’ burning hunger for more and more blood. Gladiators became as sports hero are today: celebrities. An example of this can be seen in these lines in a history of the great latin textbook by Theodor Mommsen, “Suspirium puellarum Tr. Celadus Oct. III III” (translation: “Sigh of the girls, the Thracian, Celadus, of Octavius. 3 (wins of) 3”). 4 Student 5 Some of this admiration is still preserved until today, saved by the volcanic ash that buried Pompeii. Since its recent discovery, Pompeii has provided a veritable wealth of information on gladiators with its nearly intact amphitheater and, more importantly, graffiti. This, as there is little writing of the lower classes around today, is a gateway into the personality of the people. With this piece, we can see that the lower class held gladiators in high regard, describing this particular one as the “sigh of the girls” and advertising his victory. As the source of so much entertainment for the lower class, gladiators became objects of worship. The successful ones were immortalized, as were the popular. The failed ones, on quite the other hand, were treated quite differently. Occidite exterminate vulnerate Gallicum, quem peperit Pria, in ista1 hora in amphiteatri corona. Obliga illi pedes membra senseus medulolam… --Kill, destroy, wound Gallicus whom Pria bore, in this infamous hour, in the ring of the amphitheater. Bind that man’s feet, arms, and innermost senses…(Mommsen) Almost taking the form of a curse, this piece demonstrates a desire for the gladiator, Gallicus, to be defeated in the games. Many must have taken excitement from the death of a fighter, whilst cheering for their favorite and jeering their opponent, generating a sense of involvement for the spectator. For the same reason modern sports fans do, this makes them feel as if they are in the arena themselves, alongside their heroes. Yes, heroes. That is most certainly what the Roman populace saw these men as. Gladiators, only slaves, had the power to move the mob. While in the social ladder gladiators were amongst the lowest of the low; yet the free citizens seemed to have aspired to them as idols from which to draw inspiration. Not only was the arena a place where Romans could enjoy their favorite pastime, but fulfilled their need to know that life could be better. The Latin word, iste, ista, istud has a negative connotation, and can be correctly translated as “that dastardly.” This may allude to infamy or further hatred towards the opponent, Gallicus. Or the author may be subtly conceding to the idea held by many intellectuals that this combat is, in and of itself, negative. 1 5 Student 6 Yet, as it is rather clear that this form of bloodsport filled a need for Roman people, giving them entertainment, only the lower class has been covered thus far. What of those of affluence, who could afford an education, who have developed a more intellectual set of moral standards? It can be quite understandable that this group may not have the same point of view on the subject of gladiators as the lower class. Luckily for researchers, much of the writings of intellectuals have survived until today, not needing a volcanic eruption to preserve them. Transcribed and protected for today’s readers, the works of many authors, ranging from Cicero to Seneca, still exist and are printed in books and available online. However, you can notice a common trend in the writings that have survived, those of importance, those of the intellectuals. All of them, contrary to those examined thus far, seem all to lead to a different idea: that this form of entertainment was brutal and simply wrong. For the most part, these scholars condemned the practice, much in the same way modern Americans view it. Casu in meridianum spectaculum incidi, lusus exspectans et sales et aliquid laxamenti quo hominum oculi ab humano cruore acquiescant. Contra est: quidquid ante pugnatum est misericordia fuit; nunc omissis nugis mera homicidia sunt… --By chance, I cut into a midday session, expecting some fun, wit, and relaxation, at which men’s eyes don’t enjoy the slaughter by their fellow men. It was the opposite: there were previous combats, having compassion. Now all the little trifles are put aside and it is homicide…(Seneca Minor) Seneca the Younger was perhaps the leading humanitarian in the classical period, having written his Epistulae Morales, letters of grievance. Many of his letters, including this, the seventh, take a negative tone towards gladiators. Seneca, according to his written record stumbled upon what is most likely a state form of execution to amuse the masses. He goes on later saying the officials to have not let the combatants wear armor as it would slow down the process. As the sight of death is one of the driving reasons for gladiatorial shows to exist in the first place, this is not an uncommon scene. 6 Student 7 Of course Seneca, being of rather high intellect, having an education, and with a history of moral questioning, is quite taken aback by this. To him, as can be gathered from his writing the acts of what he calls “homicide” are brutal. He stood in disbelief that the others in the audience were able to bear the “slaughter of their fellow men.” The philosophical crowd held a certain set of beliefs, dictating that this “sport” was wrong an immoral, whilst most of the lower class, as seen more through their historical impact rather than writing, would be cheering and taking a significant amount of entertainment from this. This historical impact is seen in the presentation of sheer facts, numbers, and accounts: Navalis proeli spectaclum populo dedi trans Tiberim in quo loco nunc nemus est Caesarum, cavato solo in longitudinem mille et octingentos pedes, in latitudinem mille et ducenti, in quo triginta rostratae naves triremes aut biremes, plures autem minores inter se confilxerunt; quibus in classibus pugnaverunt praeter remiges millia hominum tria circiter. --I dedicated to the people a spectacle of a naval battle, in the location across the Tiber where the grove of the Caesars is now, with the ground excavated in length eighteen hundred feet, in width twelve hundred, in which thirty beaked ships, biremes or triremes, many other smaller, fought among themselves; of which three thousand men fought as well as the rowers. (Augustus) It couldn’t have been an easy undertaking to construct a massive aquatic arena, in which to stage a real naval battle, employing such massive ships as triremes and including “three thousand men… as well as the rowers.” The costs must have been nothing short of gargantuan. This would have only been done assuming there was some justification for the ever increasingly large amounts of money spent on the contests. The populace would not have the monetary means with which to compensate, through entry fees (if any), the government’s expense. There must have been some ulterior motive for this, as the costs would greatly outstrip the revenues. The reason must lie in the general 7 Student 8 populace’s entertainment. As reason would dictate, a happy populace is a content populace, and a content populace is far less likely to rebel, ensuring tranquility. Life in much of the Roman Empire, at the very least for the commoners, was rather pitiful. The cities were overcrowded; houses and apartments were made out of kindling; disease ran wild. Despite having amenities such as plumbing, the general populace was no better off than a household slave. Gladiatorial combat was a way to get away from the droning monotony of the day to day grind. But, being so exciting, it soon became a national pastime. Intellectuals, on the other hand, did not approve: iam vero propria et peculiaria huius urbis vitia paene in utero matris concipi mihi videntur, histrionalis favor et gladiatorum equorumque studia: quibus occupatus et obsessus animus quantulum loci bonis artibus relinquit? --Now there are characteristic and peculiar vices in this city, which seem to me to be born in the mother’s womb, the obsession with actors and the passion for gladiatorial shows and horse racing: how much room does a mind preoccupied with such things have for the good arts? (Tacitus) Tacitus describes the games, not so much as needless bloodshed, as a “vice.” He describes, rather implies, viewers of such as simple people, who lack the intellectualism to take enjoyment from what he calls “good arts.” He likely thinks of gladiatorial games as more of a waste of time, with which one could use for more constructive purposes. However, his tone is more of an extremist, also dragging horse racing and theater down to the level of gladiatorial games, perhaps trying to prove his superiority over the general populace. Yet, he does seem to concede to the idea that gladiatorial combat is wrong, along with other intellectuals, such as Seneca. Further authors, such as Juvenal, take a different tone towards the games, making fun of them and those who support them, rather than to damn them and demean them. Juvenal tells a fictional story of Gracchus, the name of a prominent Roman senator who could often be seen amongst the masses in the spectators’ stands in the Coliseum. 8 Student 9 …haec ultra quid erit nisi ludus? et illic dedecus urbis habes, nec murmillonis in armis nec clipeo Gracchum pugnantem aut falce supina; damnat enim talis habitus [sed damnat et odit, nec galea faciem abscondit]: mouet ecce tridentem. postquam uibrata pendentia retia dextra nequiquam effudit, nudum ad spectacula uoltum erigit et tota fugit agnoscendus harena… --Here in the arena is there a game? That is a disgrace to the city, not with the weapons of a murmillo, not with a shield, Gracchus fights nor does he hold a shield [but damns them and doesn’t cover his face with a visor]: look, he carries a trident. After he shakes his net with his right hand he throws and misses, then for all to see he holds his naked face up and flees around the whole arena, easily recognizable. (Juvenal) Gracchus, in this short poem is being made a mockery of. Humiliated by the end of the short story, Gracchus is used to make a point. The poet, Juvenal, along with Seneca and Tacitus, takes a stand against gladiatorial combat similar to many intellectuals. He disapproves of the idea many noble born, perhaps less intelligent, individuals have to enter the gladiatorial games themselves. As one who scorned the idea of gladiatorial combat, Juvenal, in a comedic tone, writes a short poem about Gracchus, a Roman senator, who entered the arena. Foolishly, he doesn’t carry armor or a powerful weapon and pays the price. He is publicly humiliated in front of all. This shows the author’s (and many other intellectuals’) sentiments regarding gladiators. The most powerful orator in Roman history was none other than Marcus Tullus Cicero; whilst perhaps not as intellectual as others such as Seneca, he had by far the greatest gift for persuasion. It was he who called for the death of Catullus, following his rebellion, and succeeded. It was Cicero who, as a lawyer, defended many cases of capital crimes, including that of Caelius. It was Cicero who attained the rank of First Consul, making him the most powerful man in late republican Rome. 9 Student 10 quo modo illi, qui bene instituti sunt, accipere plagam malunt quam turpiter vitare! quam saepe apparet nihil eos malle quam vel domino satis facere vel populo! mittunt etiam vulneribus confecti ad dominos qui quaerant quid velint; si satis eis factum sit, se velle decumbere. Quis mediocris gladiator ingemuit, quis vultum mutavit umquam? --Gladiators, rather ruined men or barbarians, overcome as many blows as possible! These few men, who are of good training, prefer to accept blows than to live shamefully! Often it appears, those men to prefer nothing more than to make satisfied their master or people! They also send, having been exhausted by wounds, to their master who decides what they wish; if the deed is satisfactory he is to lie down. What average gladiator would groan and make himself effeminate? (Cicero) Yes, even the great Cicero himself spoke out against gladiatorial shows. However Cicero took a far less extreme approach to this argument, as he had an office to protect. He, rather than to insult those who took enjoyment from the games, decided to evoke sympathy from spectators and from other intellectuals, on likely a more humanitarian campaign rather than his usual drive for self-empowerment. Cicero, in this speech might have likely tried to rally support behind his goal to ban this form of sport. Liber Quartus: Conclusio Cicero’s was a crusade which would only take effect far into the future. The gladiatorial games persisted for centuries under the Caesars and their simultaneous campaigns to conquer the known world. It was not until the Christians were made powerful that a definitive end to the games was in sight. Under the first Christian emperor, Constantine, with his Codex Theodosianus, the sport was finally banned from the city of Rome. 10 Student 11 CTh.15.12.1 Imp. constantinus a. maximo praefecto praetorio. cruenta spectacula in otio civili et domestica quiete non placent. (thelatinlibrary.com) --CTh.15.12.1 Imp. Constantine A. By the highest order of the government decree that bloody spectacles are not suitable for civil courtesy and domestic quiet. In this, the Theodosian Code, the sport of gladiatorial combat finally met its end in Rome, much to the dismay of thousands of Pagan citizens, dying to see more of what they grew up to love. The decline of the games directly corresponds with the decline of the Western Roman Empire, who owed much of their civil order to the games providing entertainment to the commoners. 11 Student 12 Works Cited Agustus, Caesar. "Res Gestae." The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006 <http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/resgestae.html>. Cicero “Tusculanarum Disputationum 41.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006 < http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cicero/tusc.shtml>. “Codex Theodosianus.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006 <http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/theod.html>. Juvenal “Satura.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006. <http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/juvenal.html>. Petronius “Satyricon 117.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006. < http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/petronius1.html>. Seneca Minor, “Epistula Morales VII.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006. < http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/sen/seneca.ep7.shtml>. Tacitus, “Dialogues.” The Latin Library. June-July 2006. 4 Sept. 2006. < http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/tacitus/tac.dialogus.shtml>. Theodor Mommsen, The History of Rome, vol. 1. Trans. William Dickson. London: Routledge/Thoemmes, 1996. 12