Gladiators and The Roman Life

advertisement

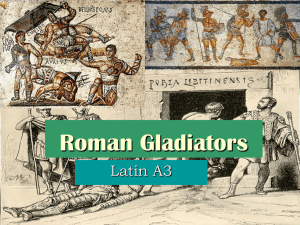

Discussion Questions: These will be the basis of your quizDescribe the origins of the gladiator games. Describe the colosseum designed by Vespaisian. Describe the process of choosing gladiators and the different types of gladiators. Describe the atmosphere found at most gladiatorial games. Describe how the game ended for each gladiator. Read the following information and write one sentence (10 – 12 words per sentence) for each paragraph. On the particularly detailed paragraphs you may write two sentences. These sentences are your notes to be written Cornell style in your notebooks. The Roman Gladiator: History & Origin Like sporting events in many ancient cultures, Roman gladiatorial combat originated as a religious event. The Romans claimed that their tradition of gladiatorial games was adopted from the Etruscans, but there is little evidence to support this. The Greeks, in Homer's Iliad, held funeral games in honor of the fallen Patroklos. The games ended not in the literal death of the participants, but in their symbolic death as defeated athletes, unlike succeeding Roman gladiatorial combat. The Roman historian Livy wrote about the first known gladiatorial games, held in 310 BCE by the Campanians (9.40.17). These games symbolized the re-enactment of the Campanians' military success over the Samnites, in which they were aided by the Romans. The first Roman gladiatorial games were held in 246 BCE by Marcus and Decimus Brutus in honor of their father, Junius Brutus, as a munus or funeral gift for the dead. It was a relatively small affair that included the combat of three pairs of slaves in the Forum Boarium (a cattle market). From their religious origins, gladiatorial games evolved into defining symbols of Roman culture and became an integral part of that culture for nearly seven centuries. Eventually gladiatorial games reached spectacular heights in the number of combatants and their monumental venues. For instance, in 183 BCE it was traditional to hold gladiatorial games in which 60 duels took place. By 65 BCE, Julius Caesar had upped-the-ante by pitting 320 ludi, or pairs of gladiators, against one another in a wooden amphitheater constructed specifically for the event. At this point, gladiatorial games expanded beyond religious events, taking on both political and ludic elements in Rome. Gladiators and The Roman Life The Colosseum is one of Rome's most famous buildings. Initiated by Vespaisian, the official opening ceremonies were conducted by emperor Titus in AD 80. In its prime the huge theater consisted of four floors. The first three had arched entrances, while the fourth floor utilized rectangular doorways. The floors each measured between 10,5-13,9 meters (32-42 feet) in height. The total height of the construction was approximately 48 meters (144 feet). The arena measured 79 x 45 meters (237-135 feet), and consisted of wood and sand. (The word "arena" is derived from the Latin arena, which means "sand.") Nets along the sides protected the audience. The Colosseum had a total spectator capacity of 45,000-55,000. The main pedestals were built of marble blocks weighing 5 metric tons (11,000 pounds.) Initially the huge marble blocks were held together by metal-pins. However, the pins were soon carried off by thieves, and had to be replaced by mortar. The total amount of marble needed for the construction measured approximately 100,000 cubic meters. It was carried by 200 ox-pulled carts, which supplied a sufficient flow of needed materials. It took eight years to complete this magnificent structure. Gladiators "Caladus, the Thracian, makes all the girls sigh." (Slogan scrawled on a wall at Pompeii. Gladiators were often sex symbols) The gladiators who fought in these games were mostly prisoners, slaves and criminals who trained long and hard in schools like the one Caesar built; although a few such fighters were paid volunteers. Some of the latter became involved because they had financial difficulties, and these events offered generous prize money for the winners. Other volunteers were motivated by the physical challenge and appeal of danger or the prospect of becoming popular idols and sex symbols who could have their pick of pretty young women. Among the graffiti slogans still scrawled on walls at Pompeii, the famous Roman town preserved under a layer of volcanic ash, are: "Caladus, the Thracian, makes all the girls sigh," and "Crescens, the net fighter, holds the hearts of all the girls." The terms "Thracian" and "net fighter" referred to the customary division of gladiators into various types and categories. Among the four main types that had evolved by the early Empire was the heavily armed Samnite, later called a hoplomachus or secutor. (The Romans may have recognized these three as separate and distinct types, but any such distinctions are now unclear; all employed basically the same weapons and tactics.) A Samnite carried a sword or a lance, a scutum (the rectangular shield used by Roman legionary soldiers),a metal helmet, and protective armor on his right arm and left leg. Another type, the Thracian (so named because he resembled fighters from Thrace, a region of northern Greece), was not as elaborately armed. He wielded a curved short sword, the sica, and a small round shield, the parma. A third kind of gladiator, the murmillo, or "fishman" (after the fishshaped crest on his helmet), was apparently similar to a Samnite but less heavily armed. A murmillo customarily fought still another kind of warrior, the retiarius, or "net-man," who wore no armor at all. A retiarius attempted to ensnare his opponent in his net (or used the net to trip the other man) and then to stab him with a long, razorsharp trident, or three-pronged spear. In addition to the pairings of these main gladiator types, there were a number of special and off-beat types and pairings. These included equites, who fought on horseback using lances, swords, and/or lassoes; the essedarii, who confronted each other on chariots; and, perhaps the most bizarre of the lot, the andabatae, who grappled while blindfolded by massive helmets with no eyeholes. Women gladiators came into vogue under the emperors Nero and Domitian in thee late first century A.D. Evidence shows that Domitian sometimes pitted female fighters against male dwarves as well as against one another. "We Who Are About to Die Salute You!" On the eagerly anticipated day when munera were scheduled at the Colosseum or another amphitheater, the gladiators first entered the arena in a colorful parade known as the pompa. This was similar in some ways to the procession of the athletes on opening day of the modern Olympic Games. They were usually accompanied by jugglers, acrobats, and other performers, and all kept time to marching music provided by musicians playing trumpets, flutes, drums, and sometimes a large hydraulic organ. (The organ probably also played during the actual fighting, producing the same effect as the background musical score of a movie.) Following the pompa, the acrobats and other minor performers exited and the gladiators proceeded, in full public view, to draw lots, which decided who would fight whom. Then an official inspected their weapons to make sure they were sound and well sharpened. Finally, the gladiators soberly raised their weapons toward the highest-ranking official present (usually either the emperor or munerarius, the magistrate in charge of the spectacle) all recited the phrase, "Morituri te salutamus!" ("We who are about to die salute you!") After that, the first pairing began. Having no rules or referees, the combat was invariably desperate and often savage. The spectators, like those at modern boxing matches and bullfights, reacted excitedly. Typical shouted phrases included "Verbera!" ("Strike!"), "Habet!" ("A hit!"), "iHoc habet!" ("Now he's done for! "), and "Ure!" ("Burn him up!").The fighting had several possible outcomes. If both warriors fought bravely and could not best each other, the munerarius declared the bout a draw and allowed them to leave the arena and fight another day. Sometimes both officials and spectators felt that the fighters were not giving it their all. Or one man turned and ran. "Officiosus fled on November 6 in the consulate of Drusus Caesar and M. Junius Norbanus," reads a Pompeian inscription. Such offenders were punished by whipping or branding with hot irons. A more common outcome was when one gladiator went down wounded. He was allowed to raise one finger, a sign of appeal for mercy, after which the emperor or munerarius decided his fate, usually in accordance with the crowd's wishes. If the spectators desired a fighter spared, they either waved their handkerchiefs or pointed their thumbs downward, the signal for the victor to drop his or her sword. At the same time they shouted "Mitte! ("Spare him!") On the other hand, if the choice was death, they Pressed their thumbs toward their own chests (symbolizing a sword through the heart) and yelled "lugula!" ("Cut his throat!"). Another possible outcome was when one fighter killed an opponent outright; and still another when the fallen combatant pretended to be dead. Few, if any, were successful at this ruse, for men dressed like the Etruscan demon Charun (a retained custom illustrating the games Etruscan roots) ran out and applied hot irons to the bodies. Any fakers exposed in this way promptly had their throats cut. Then young boys cleaned the bloodstains from the sand, and men dressed as the god Mercury (transporter of tile dead) whisked away the corpses, all in preparation for the next round of battles. Test and pictures from Greek and Roman Sport by Don Nardo