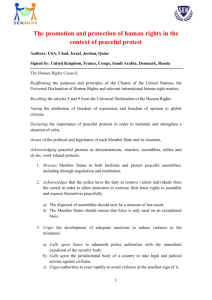

Effective measures and best practices to ensure the promotion and

advertisement