A New Comprehensive Database of Hand

advertisement

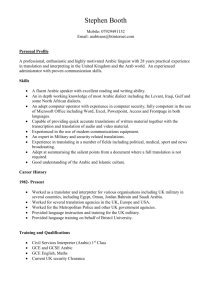

A New Comprehensive Database of Hand-written Arabic Words, Numbers, and Signatures used for OCR Testing Nawwaf Kharma. Maher Ahmed, & Rabab Ward E.C.E. Department, (289-) 2366 Main Mall, University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, Canada. V6T 1Z4. Phone: 604- 822 1742. Fax: 604- 822 9013 Nawwaf@ieee.org, MaherA@ece.ubc.cai & RababW@cs.ubc.ca Abstract This paper describes the formation of a comprehensive database of handwritten Arabic words, numbers, and signature, for use in optical character recognition research related to the Arabic language. So far no such (freely or commercially available) database exists. 1 Introduction The construction of software programs for the recognition of characters and words is an involved engineering pursuit. The quality of the resulting software depends, to a great degree, on the thoroughness of testing, both during and after the development stage. Many hand-writing related applications are concerned with off-line uses, such as formfilling and signature confirmation. In such situations, there is no (direct) control on the style of writing applied by the user. Overlapping and badly formed characters, as well as missing dots are common occurrences. The above mentioned type of practical problems necessitates the utilisation of a database of naturally written characters, numbers and other gestures, in order to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of the developed software. Especially in the case of the Arabic language, there exists no freely or commercially available (or Internetaccessible) database of Arabic characters, numbers, and signatures. This, specifically, is the purpose of the research work described here. 2 Background Much work has been carried out in Arabic character & word recognition. Doubtless, some of this work relied on privately collected and kept databases of Arabic printed and hand-written text. However, and despite a determined lengthy paper & Internet search campaign, no publicly accessible Arabic database was found. This must be a source of genuine hindrance for many researchers into Arabic character & word recognition. Hence, and though our own work [2] was on on-line (as opposed to offline) Arabic character recognition, it was decided that such a database, on its own merit, is a worthwhile academic effort. An effort, which would, if properly conducted, provide researchers with a useful tool. In addition, it is envisioned that, with the right thinning and tracing techniques, a determined researcher of on-line recognition, would be able to salvage the temporal order of writing, and as a result, use the same database for his/her testing needs. 3 Collection of Data Hand-written Arabic words, numbers, signatures, and complete sentences were the object of the data collection effort, which took place at AlIsra’ University in Amman, Jordan. Five hundred randomly selected students took part in the exercise. Each student was asked to copy a pre-selected list of words and digits, as well as a sentence. He/she also jotted his/her signature 5 times at the bottom of the distributed (standard) form. The words were chosen carefully to ensure that they contain (at least once) each of the letters of the Arabic alphabet, in their various letterforms (e.g. middle and end.) As to numbers, both the ‘Magharibi’ (North African) and ‘Mashriqi’ (Middle Eastern) digit sets were requested. The single sentence (a line of poetry) was included in the form to provide the database user with a snapshot of the way in which a native writer forms a whole sentence, while using short vowels (or ‘tashkeel’) and punctuation marks. Finally, the signatures came in all forms, but all were written either in Arabic or (not unusually) in English. It is worth noting that a couple of restrictions were placed on the writer. The standard form contained (rather big) boxes for the writer to script his/her written response (e.g. word) in. Also, and with the exception of the sentence, no base line was provided. This made the (following) process of cleaning the black & white images much easier, and more correct. 4 Scanning, Digital Manipulation & Storage of Data The paper forms collected from the students were all scanned. The scanned images were segmented, in some cases cleaned up, and saved in logically named computer files, first on a hard disk, and then on compact disk (CD). Scanning was done using an HP truecolour capable scanner. However, it was decided that allowing colour would hugely increase the size of the files, without necessarily adding a popularly demanded feature. The forms were indeed scanned as (sharp) grayscale and (sharp) black & white (or b&w) images. The images were saved in bitmap (or .bmp) file format, because this format is standard, and is very easy to use by computer programs. Once scanning was completed, the image of the page was digitally manipulated, according to its contents, in the following manner. Words in grayscale are cut out of the image, and saved in bitmap files. Words in b&w however, are cut out of the image, borders as well as noise are manually removed, and then the image is saved in a bitmap file. In the case of numbers, each grayscale digit is cut out of the image and saved in its own .bmp file. In contrast, digits in b&w are cut out of the image, all borders and noise are manually removed, and then each digit is saved in a separate file. Signatures were also written in boxes. As with words and numbers, grayscale signatures were simply cut out of the original image and placed in separate .bmp files. On the other hand, b&w signatures were cleaned up before being saved in bitmap files. Sentences are a different story. No cleaning up was done, neither in the grayscale nor in the b&w case. In both cases, the sentence was simply cut out of the image and saved in a .bmp file. The reason for not cleaning up the b&w sentences is that doing so would mean removing the base-line something that was never intended. 5 Thinning of Images On top of saving images in b&w and grayscale .bmp formats, a thinning algorithm developed by Ahmed [1] was applied to all the b&w image files. The output of this application was also saved in bitmap files, sorted according to their contents, into word, number, signature, and sentence files. The purpose of this application is to provide researchers with a readily available version of the original image files. The thinning algorithm in [1] has just 16 rules. These rules aim at deleting the pixels which are north-west corner pixels or pixels that lie in the east boundaries or south boundaries of the designated pixel (being processed). The conditions for 2-pixel thickness lines are given special attention. The original 16 rules are transformed by rotating them by 90o, 180o, and 270o to produce three more sets of rules. The 64 rules (composed of the 16 rules and their rotated versions) are applied on every pixel, and in one pass. 6 Conclusion & Future Work The final resultant of all the collection and processing work described is: - 37,000 Arabic words, - 10,000 digits (in two types), - 2,500 signatures, and - 500 free-form Arabic sentences, all saved in grayscale and black and white .bmp file formats and ready for use. Copies of the database CD will be offered to researchers in Canada, as of May 1999, and (only partially) to the rest of the world, once it is placed on the Internet. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to everyone at Al-Isra’ University who participated in the data collection stage. I would also like to express my gratitude to my wife, Aida, for her patient and persistent help in scanning the forms. References [1] Ahmed, M. and Ward, R., “A rule-based system for thinning symbols to their central lines,” submitted to the IEEE journal of PAMI in June 1998. [2] Kharma, N. and Ward R., “A novel invariant mapping applied to hand-written Arabic Character Recognition” submitted to Character Recognition Letters in January, 1999.