Chapter 13 Notes - Herbert Hoover High School

advertisement

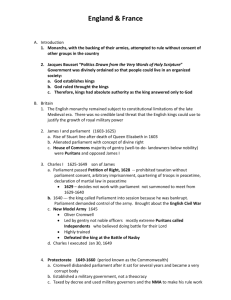

Chapter 13 European State Consolidation in the 17th and 18th Centuries The Netherlands Until the 16th century, the Low Countries – the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg or the Seventeen Provinces – consisted of a number of principalities. As we have seen, during the fifteenth century, most of these provinces came under the House of Burgundy and subsequently the House of Habsburg. In 1549, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (who was proud of his title Duke of Burgundy) issued the Pragmatic Sanction, which consolidated the Seventeen Provinces under his rule. In the last chapter we saw how Charles’ son Philip II in 1567 set out to make an example out of the Calvinistleaning Dutch and turned the Duke of Alba’s terror on the land; and then in 1568 the William I of Orange, led a rebellion because of high taxes, religious persecution, and Philip's efforts to centralize the local government (i.e., taking away many local and customary prerogatives from the provinces). This led to the Eighty Year’s War. In 1579, seven Northern provinces signed the Union of Utrecht, to protect each other from Spain - and this marked the formal beginning of the Dutch Republic. Spain was forced to recognize the Union of Utrecht in 1609 and in 1648 the Treaty of Westphalia (ending both the Eighty Year’s War and the Thirty Year’s War) gave European recognition to an independent Dutch nation and affirmed Spanish (Hapsburg) control of the Spanish Netherlands. During the seventeenth century, the newly independent Dutch fought a series of naval wars with England. Then in 1672, Louis XIV of France and the English invaded the Netherlands. All looked lost until Prince William III of Orange (1650-1702 - who was the grandson of William the Silent, the principal leader of the Dutch revolt against Spain) became the Stadtholder (chief executive), and rallied the Dutch; eventually defeating the Anglo French fleet and leading a European coalition against France and England. William even married Mary, the (Anglican) daughter of James II of England and in 1688, when James II was forced to flee England in the Glorious Revolution, became King William III of England (note he was still Stadtholder William III of Orange) with Mary becoming Queen Mary II. Government: The Netherlands never had a strong sense of centralized government and preferred a governmental pattern in which each of the provinces had considerable autonomy (self-governance). There was a central government, the States-General, which met in The Hague (a city in the province of South Holland) and shared sovereignty with the provinces. But although the Netherlands was a republic, it also had a monarch (the Stadtholder) whom the Dutch generally mistrusted and marginalized (treated insignificantly) except in times of emergencies, when the monarchs (i.e., the House of Orange) were allowed to assume leadership. This political model proved highly resilient and successful; and allowed the Dutch to establish their republic among the other European states. After a crisis passed, the StatesGeneral would reassert its leadership, such as when William III died and the Dutch would revert to its republican governmental structure. Religion: The Netherlands was predominately Calvinist and the Calvinist Reformed Church was the official church of the nation. Nevertheless, it was not an established church; that is, it was not endorsed by or financially supported by the state. Unlike Calvinists in many other places, Dutch Calvinists were uniquely tolerant of Roman Catholics, other Protestant groups and even Jews. This toleration made the Netherlands stand alone in comparison to almost every other European state, most of whose rulers or religious majority often sought to impose a single religion on the country. This toleration also helped the Netherlands avoid religious conflicts which created bloodshed and social chaos in so many other nations. 1 The Economy: Most astonishing – especially to other Europeans - was Dutch prosperity. During much of the seventeenth century, the Netherlands was the wealthiest nation in Europe. The foundations for such prosperity were manifold (many and varied). The first was the growth of Dutch of cities (or high urban concentrations) which – on average - were more populous than most other cities in Europe. The second was that the Dutch became more efficient farmers by creating farming techniques which leaped out ahead of the rest of Europe and released surplus farmers (farmers no longer needed to farm) to move into the cities. The Dutch drained flooded land and reclaimed it from the sea, which they then used to increase crop production. This in turn allowed them to create highly profitable grain crops along with dairy, beef, and cash crops such their famous tulips. A Third Foundation of Dutch prosperity was industry. Dutch fishermen dominated the Herring markets and supplied Europe with enormous quantities of dried fish. They also had a thriving textile industry and exported fine tapestries and other cloth products to much of Europe. The Dutch created an enormous shipbuilding industry and Dutch merchants called in all European ports, buying and selling goods of all kinds. Many economic historians regard the Netherlands as the first thoroughly capitalist country in the world. Amsterdam was the wealthiest trading city in Europe and the home of Europe’s the first full-time stock exchange founded in1602. This economic ingenuity also led to such concepts as insurance and retirement funds, bull and bear markets and asset inflation bubbles such as the Tulip Mania of 1636–1637. The tulip is a bulb that produces a beautiful flower. It was originally imported from Turkey in the 16th century and became increasingly valuable because of its beauty. By 1636, the tulip mania (that is investments in tulips) peaked with investors speculating on the value of the tulip, and, when the market crashed, investors lost as much as 95 percent of their original investments. The Final Foundation for Dutch prosperity was the Dutch Empire, which grew to become one of the major seafaring /economic empires of the 17th century. This was the Dutch Golden Age, in which colonies and trading posts were established all over the world. Dutch settlement in North America began with the founding of New Amsterdam, on the southern tip of Manhattan Island (Modern New York City) in 1614. In South Africa, the Dutch settled Cape Town in 1652. But it was in East Asia, in what came to be called the Dutch East Indies (roughly modern Indonesia) where the Dutch built an incredibly lucrative spice trade. The vehicle for these financial successes was the Dutch East India Company (chartered in 1602), which displaced the Portuguese in the Southeast Asia and gave the Dutch an empire that would last until after World War II. Two amazing statistics are that by 1650, the Dutch owned 16,000 merchant ships and that by 1800; the Dutch population had increased from about1.5 million to almost 2 million. The eighteenth century saw the decline in the wealth and political influence of the Provinces of the Netherlands. After the death of William III of England/Orange in 1702, the provinces prevented the emergence of another powerful Stadtholder. This in turn led to a lack of skilled leadership and naval supremacy slowly passed to the British; and so the Dutch were unable to compete with Britain for trade and colonies. Shipbuilding also declined and along with the fishing industry; and the Dutch lost their economic leadership in inter-European trading. Domestic industries also stagnated and the United Provinces and were furthered weakened by being forced to consistently resist the French who greedily wanted to absorb the Dutch provinces. What saved the Netherlands from insignificance or French absorption was continued dominance in the financial markets and European trade, especially the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. 2 Parliamentary Monarchy vs. Political Absolutism The Republic of Venice with its Council of Ten, the Republic of Florence and the Swiss cantons were republics without a strong monarch. The Dutch were a republic sometimes with a strong Stadtholder but other times without. But these were the exceptions! In seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Europe saw the formation two kinds of government: Parliamentary Monarchy and Absolute Monarchy. England embodied the first and France the second. England: From the Stuarts to the Hanoverians James I In 1603, the much beloved Queen Elizabeth I of England died and was succeeded by her cousin, the son of Mary Queen Scots, James VI of Scotland who came to the throne because he was the next-inline of succession because he was the grandson of Henry VII through Margaret Tudor, the older sister of Henry VIII. He thus united the thrones of England and Scotland as James I of England peacefully but still faced many challenges. The first was the fact the Elizabeth had worked well with Parliament, so well in fact, that Parliament met only when she called it into session. The second was the fact that, as head of the Church of England, he was head of a bitterly divided church. James would complicate both issues because he was determined to rule according to the Divine Right of Kings, which asserted that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority. In Chapter 10, we were introduced the author of this theory, Jean Bodin (1530-1596), who wrote a 1576 treatise, The Six Lives of the Republic, in which he defended the sovereign rights of a monarch in his famous quotation that The Sovereign Prince is accountable only to God.] Thus James wished to call Parliament into session as infrequently as possible. But he needed money; so he turned to a source of income called Impositions, which was the charging of customs duties on imports such as tobacco. Many in Parliament felt that the king was usurping their authority but did not want a serious confrontation. So for most of James’ reign, he and Parliament squabbled and negotiated. Moreover, James was an ardent (devout) Anglican and soon came into conflict with the Puritans who wanted to replace the liturgical and sacramental ceremonies of the Church of England along with Episcopal form of government (by bishops not presbyteries). What the Puritans wanted was a Presbyterian form of church government like the Calvinist churches in Scotland, the Netherlands and Switzerland. At the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, James rejected all of the Puritan demands, which led to deepening distrust between Anglicans and Puritans. Many religious dissenters began to leave England. In 1620, Puritan separatists (or Pilgrims) founded Plymouth Colony on Cape Cod Bay in North America and were soon followed by better financed Puritans who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony - and later Boston in 1630. In both cases, the Puritan exiles preferred to leave England because they felt that the Reformation had not gone far enough - and that only in America could they organize a truly reformed church where they could freely worship. The Hampton Court Conference also ordered a new translation of the Bible (published in 1611), which in England is called the Authorized Version but in America the King James’ Bible. James’ court also became a center of scandal and corruption. James was unduly influenced by favorites of whom the most influential was the Duke of Buckingham, who was suspected of being the king’s lover. Be that as it may, Buckingham controlled royal patronage (that is, choosing who got the king’s financial or political support) and openly sold peerages (or titles) to the highest bidders – a practice that angered the old nobility because it cheapened the nobility as a whole. Kings had always had favorites, but never had one favorite of a king had so much power and access to the monarch. 3 Most of England was Anglican but decidedly Protestant and bitterly anti-Roman Catholic. James’ foreign policy called his Protestant loyalty into question. In 1604, for example, he concluded a peace treaty with Spain ending a ruinously expensive war but casting him in a pro-Catholic image. James also tried (for unity and toleration) to ease penal laws against Catholics and in 1618 wisely hesitated to send troops to assist the Protestant forces in Europe at the outbreak of the Thirty Years War also made him suspect in Protestant eyes. Perhaps worst of all in the eyes of the English was his attempt to marry his son, Charles, to a Spanish princess and then, when that failed, arranging a successful marriage between his son Charles and Henrietta Maria, the Catholic daughter of Henry IV of France. Charles I In 1624, England and Spain were again at war as participants in the Thirty Year’s War. In early 1625, James died and Charles came to the throne. Parliament supported the war but would not adequately (fully) finance the war because it distrusted the new king. Charles could not use Impositions because his father had given up that right so, like his father, Charles went around Parliament (and its restrictive purse strings) in other ways, by attempting to collect discontinued taxes and forcing English property owners to pay Forced Loans (that theoretically would be repaid). If property owners refused to make this loan-really-a-tax, they were imprisoned. All these tactics as well as quartering (housing) troops in private homes angered the local nobility and landowners. When Parliament met in 1628, its members agreed to grant Charles much needed funds only if Charles would assent (agree) to the Petition of Right, which forbade taxation (including Forced Loans) without the consent of Parliament, the quartering of soldiers in private homes, imprisonment without (sufficient) due cause and the use of martial law except under specific conditions. Charles was forced to give his approval to the petition but most people believed that he would NOT keep his word. Nevertheless, the Petition of Right is considered one the most important documents in English constitutional history, ranking with Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights of 1689; and heavily influencing the American Constitution including the American Bill of Rights. In the following year after quarreling with Parliament about money, Charles dissolved Parliament and ruled without calling Parliament into session for eleven years until 1640. In order to rule without Parliament, Charles did two things: first, he made peace with Spain in 1630, thus making his Protestant Anglican subjects suspicious of his being possibly sympathetic with Roman Catholic powers. Second, he had his chief advisor, Thomas Wentworth, (Duke of Strafford (1593-1641), not only impose strict efficiency and governmental centralization but also to exploit every “legal” fund-raising device such as enforcing neglected laws and stretching existing laws. Charles might have ruled this way indefinitely were it were not for his religious policies. Unlike Elizabeth and his father, who allowed a wide variety a religious opinion and expression, Charles was determined to enforce Anglican religious conformity not just on England but on (Calvinist) Scotland and (Catholic) Ireland. A crisis point was reached in 1637, when Charles’ Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud tried to force the Anglican Book of Common Prayer and Episcopal system of church government on the Calvinist-Presbyterian Church in Scotland. The Scots immediately rebelled and Charles, who was financially unprepared for war, was forced to call Parliament into session. When Parliament met, however, it refused to even consider the king’s financial requests until the king agreed to correct their grievances. The king immediately dissolved Parliament; hence its name the Short Parliament (AprilMay, 1640). However a few months later, the Scots defeated Charles’ army at the Battle of Newburn and Charles was forced to again call Parliament into session. This time, Parliament was in no mood to be conciliatory (accommodating). This Parliament would meet for twenty years and so received its name, the Long Parliament. It was dominated by three groups, all hostile to the king and his policies: the landowners, the merchant classes and the Puritans; and these latter were the angriest of all. 4 Parliament began by impeaching both Strafford and Laud; both were executed: Strafford in 1641 and Laud in 1645. The Long Parliament also abolished the courts that enforced royal policy and prohibited the levying of new taxes without its consent. Finally, it declared that not more than three years should elapse between its meetings (known as the Triennial Act of 1641) and that the king could not dissolve Parliament without Parliament’s consent. Parliament, however, was deeply divided along religious lines. The moderate Puritans or Presbyterians and the radical Puritans or Independents/Dissenters wanted to abolish Episcopal governance (church run by bishops) and the Book of Common Prayer but the Anglican party was determined to preserve the Church of England as it currently was; that is to keep the status quo. These divisions intensified in late 1641, when Charles asked Parliament to raise funds for an army to suppress the Scots’ rebellion. Those opposed to the king argued that the king could not be trusted to command an army that might be used against Parliament. Rather, they wanted Parliament to direct and command the armed forces. In January 1642, Charles had his officers invade Parliament in order to arrest five members who were most responsible for opposing him. They escaped however and a shocked and angered majority of the House of Commons passed the Militia Ordinance of 1642, which gave Parliament authority to raise an army of its own. After his failure to seize hostile members of Parliament, Charles left London to raise his own army and the result was The English Civil War which lasted from 1642 to 1646. The supporters of Parliament were known as the Roundheads and the supporters of the king were known as the Cavaliers. Parliament would win the struggle for two main reasons. First, Parliament made an alliance with Scotland and committed England to a Presbyterian system of church government. Second, was the emergence of a dynamic leader, Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), who reorganized and galvanized (put new spirit into) the Parliamentary army. Cromwell was a country squire of strong, Puritan/Independent convictions He rallied followers, who like himself, would only tolerate an established church, if it permitted Protestant dissenters to worship freely outside of it. In 1645, Cromwell’s army defeated Charles’ army at the Battle of Naseby and so Charles switched tactics – and tried political (machinations) maneuvering within Parliament. Charles tried to exploit Parliament’s divisions but Cromwell’s supporters had the king’s supporters expelled. Charles was then arrested, tried for treason and executed on January 30, 1649, as a public criminal – the only king of England to ever be executed. Parliament then abolished the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Anglican Church. England became a Puritan republic – a period called The Great Interregnum. Cromwell was in almost complete control. His army conquered Scotland and Ireland, where his soldiers was guilty of especially brutal atrocities against Irish Catholics – leaving a bitter legacy that would last for centuries. At home, Cromwell who was a “no nonsense” personality proved to be no politician and so was unable to control Parliament. When the House of Commons in 1653 voted to disband his army, he simply dissolved Parliament and ruled England as Lord Protector until his death in 1658. Cromwell’s “Lord Protector –ship” however was no more than a brutal dictatorship and no more successful than the rule of Charles I. Thus Cromwell became just as harsh and just as hated as the king, the Duke of Strafford and Archbishop Laud had been. Moreover, people deeply resented his puritanical prohibitions against drinking, card playing, theatergoing and dancing. Political liberty vanished in the name of religious conformity. When Cromwell died in 1658, he was succeeded by his son, Richard, who was too weak to hold power. Moreover, the English people regretted the murder of their king and they also were tired of the dreary lives they were forced to lead under Puritan morality; thus by 1660, they were ready to restore both the monarchy and the Anglican Church. 5 Charles II Charles II, the son of Charles I, was living in exile in France when Cromwell died. He negotiated with the army, promised a general pardon and returned in late 1660 to great celebrations and festivities. Charles - much unlike his father - was a man of considerable charm and he quickly set a new, happier tone after eleven years of Puritan rigidity (He also had numerous mistresses). Under his agreement with Parliament, England was returned to the status quo of 1642 with a hereditary monarch, a Parliament of Lords and Commons (summoned when the king called it) and a restored Anglican Church which again became the state religion. Charles unlike his father, who was staunchly Anglican, had Roman Catholic sympathies and understandably favored religious toleration, especially for Puritans and Catholics. Nevertheless he was thwarted in Parliament by ultra-conservatives who pushed through a series of laws known as the Clarendon Code, which excluded Catholics, Presbyterians and Independents from official political and religious life of England. In 1670, Charles signed the Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV which formally made the English and French allies against the Dutch Netherlands and set in motion the rise of William III. In a secret section of the treaty, Charles promised to announce his conversion to Roman Catholicism as soon as conditions in England would permit. In return for this announcement (which was never fulfilled), Louis XIV promised to pay Charles a large amount of money. Although Charles did not convert, he still issued a Declaration of Indulgence in 1672, which suspended all laws against Roman-Catholics and other non-Anglicans. The Protestants in Parliament were furious and blocked funding for the war and forced Charles to rescind the declaration. Then Parliament passed the Test Act, which required all civil servants and military officers to swear an oath repudiating the doctrine of Transubstantiation, which of course no Catholic could do. The real target of the Test Act, however, was Charles’ brother James, who not only was a recent and devout convert to Roman Catholicism but was heir to the throne since Charles was childless. Tensions between Catholics and Protestants were made worse in 1678 when, Titus Oates, a notorious liar, swore before a magistrate that Charles’ Catholic wife and her physician were plotting with Jesuits and Irishmen to kill the king so James could assume the throne. Parliament tragically believed Oates and in the hysteria that followed – called the Popish Plot – many innocent people were tried and executed. Charles never forgave the leader of the anti-Catholic forces, the Earl of Shaftesbury (16211683) who led the Whigs in Parliament and tried to exclude James from succession. This drove a deeper wedge between Charles and Parliament. So Charles turned to increased customs duties (tariffs) and cash from Louis XIV so that he was able to rule without Parliament until his death. In those last years of his reign, he successfully drove Shaftesbury into exile and executed several Whig leaders. He was also able to use persuasion and intimidation to get local districts to send to Parliament members who would be sympathetic to the king. And when he died, he left a Parliament largely friendly to his crown, but it would all be for naught. The Glorious Revolution When James II became king in 1685, he immediately enlarged the army and demanded that Parliament repeal the Test Act. When Parliament refused, James dissolved Parliament and then proceeded to appoint Catholics to high positions in his court and in the army. In 1687, he issued a second Declaration of Indulgence which suspended all religious barriers for holding public office and permitted free worship for all non-Anglicans. In 1688, he arrested William Sancroft, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and six other Anglican bishops because they had refused to require their clergy to read the Declaration of Indulgence from the pulpits of their churches. All the bishops were tried for treason and all were acquitted but, needless to say, England seethed with resentment and anger against James. 6 The one hope the English clung to was that the detested James, who had two surviving daughters by his first wife, Anne Hyde (d.1671) would be succeeded by his older daughter, Mary, who was a devout Anglican and the wife of William III of Orange. But James had married again; and even worse, he married a Roman Catholic, Mary of Modena. Then on June 20, 1688, Mary bore James II a son, which meant that James had a male heir; who would be a Catholic-raised male heir – and his two daughters were put after him in line of succession. This was too much for the Protestant nobility, who then formally invited William of Orange and Mary to come to England with an army to preserve their English liberties. James refused the assistance of Louis XIV, fearing that the English would oppose French intervention; and when William landed in early November, many Protestant officials and nobility defected to William, as did James's second surviving daughter, Princess Anne, who was devoutly Anglican and would become Queen of England herself on William III’s death. As James fled fearing for his life, William and Mary were greeted as national heroes by the English people and were invited to become joint rulers in 1689, William III and Mary II. This was called the Glorious Revolution and it was glorious for two reasons. First, it was relatively bloodless; the losing side did not suffer murderous reprisals by the winners. Secondly, it marked the beginning of English Constitutional Government, when William and Mary recognized and endorsed the Bill of Rights of 1689, which limited the powers of the monarchy and guaranteed the civil liberties for the English upper classes. From this point on English monarchs were subject to the law and Parliament met every three years. The Bill of Rights also prohibited Roman Catholics from the kingship of England and the Toleration Act of 1689 permitted free worship by all Protestants and outlawed Roman Catholicism and free thinkers who denied the Trinity. Nevertheless, only members of the Church of England enjoyed full political rights. Just before William died, Parliament passed the Act of Settlement in 1701, which provided that the English crown would go to the Protestant House of Hanover in Germany if Anne (r. 1702-1714) died without children. In 1707, The Act of Union, passed by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland, formed the Kingdom of Great Britain. And so when Queen Anne died, the Elector of Hanover in Germany became King George I (r. 1714-1727) of Great Britain. Almost immediately, George I faced a Stuart challenge when the Catholic son of James II, James Edward Stuart, invaded Scotland but was defeated after only two months. George was a passive ruler, spoke no English and his reign saw the monarch’s power diminish greatly as Britain began a period of transition to its modern system of cabinet government led by a prime minister. The Age of Walpole This transition cabinet government under Parliament was guided by Sir Robert Walpole (1676-1745), a British statesman, generally regarded as the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. Walpole was supported by the king and he controlled Parliament because of his ability to dominate (lead) the House of Commons. Walpole maintained peace abroad and the status quo (existing state of affairs) at home. Under his guidance, Britain’s foreign trade expanded and planted the roots of a colonial empire that stretched from North America to India. He allowed local nobles (or gentry) and landowners to retain their local political influence and so they were willing to serve as government ministers, judges and military commanders. Thus, Walpole’s government was able to produce a strong tax base which supported Britain’s military - and particularly a strong navy. As result, Great Britain began its rise not only as a major European power but a major world power. During the Age of Walpole, Great Britain began evolving more rapidly into a democracy. The power of British monarchs was now circumscribed (had definable limits) and Parliament had to keep in mind the force or influence of popular opinion (i.e., what people thought). Members of Parliament were free to express independent views and even Walpole could be (and was) publically criticized. 7 Thus free speech became the national norm. There was no large standing army. There was significant religious toleration except for Roman Catholics but even that was relaxed (at least unofficially) as time went by. It is important to understand that British political life, religious toleration, free-market capitalism (which we shall discuss in Chapter 15) and personal freedoms became a model for all progressive Europeans who questioned the absolutism of their monarchs. And it would be these qualities that would allow Great Britain to become a strong and united nation. The Age of Louis XIV Louis XIV was born on the fifth of September 1638 to Louis XIII and Anne of Austria. At the time of his birth, his parents had been married for twenty-three years without surviving children. Leading contemporaries hailed him as a divine gift, and his birth, a miracle of God. His reign would take France to the pinnacle of its glory and yet he would sow the seeds of its destruction by his costly foreign wars and lavish spending. Nevertheless, he came to be known as Louis the Great (Louis le Grand) or the Sun King (le Roi-Soleil), and was King of France and Navarre during a reign, which lasted from 1643 to 1715; and is one of the longest documented reigns of any European monarch. During the first half of the seventeenth century, Henry IV (r. 1589-1610) and Louis XIII (r. 1610-1643) had faced strong challenges from well armed nobles and unhappy Calvinists; and only gradually did they establish the authority of the monarchy. The groundwork for the absolutism that Louis XIV exercised was laid by two powerful ministers: Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642) and Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661). Both Richelieu (who had betrayed his Catholic religion in the Thirty Years’ War) and Mazarin worked to centralize authority in the person of the king and to impose direct royal administration on France. Richelieu was also very successful in circumscribing (i.e., constricting or limiting) many of the political privileges that Henry IV had granted to French Huguenots in the Treaty of Nantes in 1598. As successful as these centralizing policies were, they eventually provoked a series of widespread rebellions among the French nobility between 1649 and 1652. These rebellions came to be known as the Fronde, which comes from the French word fronde meaning sling (a piece of leather used to hurl stones), which Parisian mobs used to smash the windows of Cardinal Mazarin and his supporters. Louis XIV was a “teenager-not-yet-a-real-king” when the Fronde exploded and, although the rebellion was put down, Louis became convinced that heavy-handed and repressive (brutal) policies were counterproductive. So Louis learned from the Fronde and managed to concentrate unprecedented power in the monarchy but in a unique manner. Louis did not attack or try to destroy the nobility and their social structures but worked with and through the nobility to make himself the head of the social establishment. At the same time, Louis also reorganized French military forces under a stricter hierarchy and made military leaders directly answerable to the king himself. Thus the Fronde, whose goal had been to free the nobility from the heavy hand of the monarch - finally resulted in the disempowerment of the territorial aristocracy and the emergence of an absolute monarchy. On the death of Mazarin in 1661, Louis assumed personal control of the French government at the age of 23. He appointed no single chief minister so that, if the nobility rebelled, they would be challenging the king directly – a strategy he used to great advantage. Louis devoted enormous energy to his political agenda. He ruled through government committees that controlled foreign affairs, the army, domestic administration and the economy. He chose council members from families who had long been in royal service or from among people just beginning to rise in the social structure. These latter – the new middle class - were more loyal to the king than older noble families who had their own power bases in the provinces far away from Paris. Louis also kept the old nobility under his eye, by requiring them to live at his grand palace at Versailles much of the year, where they were lavishly entertained in spectacular court ceremonial – and thus unable to build power bases on their estates. 8 Louis also made sure that the nobility and their social groups would benefit from the growth of his authority. As he centralized authority, he never tried to abolish the nobility. He worked with the nobility in judicial bodies called Parlements before making rulings that would affect them and he consulted them before making economic changes. On occasion he did clash with the Parlements, such as when in 1673 he clashed with the Parlement of Paris over the right to register royal laws. Louis won the dispute by requiring the Parlement of Paris to register laws before raising any questions about them much to the delight of more rural Parlements. But overall Louis’ ability to work with the old nobility brought him their support and loyalty. Divine Right of Kings Louis XIV firmly believed that he was king by divine right and this concept was given him by his tutor, Jacques-Benigne Bossuet (1627-1704) who used Old Testament examples, like King David and King Solomon, to show that kings were answerable only to God. The corollary was that the king was duty-bound to reflect and carry out God’s will in the ways in which he ruled his people and country. In effect, by the theory of the Divine Right of Kings, the king was God’s regent on earth. This assumption was reflected in Louis’ declaration L’etat, c’est moi or “The state, I am the state.” Nevertheless Louis’ absolutism did not show itself in an oppressive control of the daily lives of the people. Rather, his absolutism was an example of the European concept of looking at the larger picture in the exercise of power that would remain entrenched until the collapse of the monarchy during the French Revolution of 1789. Louis’ Early Wars By the late 1660s, France had Europe’s largest population (outside of Russia), Europe’s most efficient governmental bureaucracy, probably Europe’s best army and a strong sense of national unity. Louis depended heavily on Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683) whose economic policies made it possible for Louis to maintain his large army and fight his wars. Louis’ goal was to dominate all of Europe and he was particularly concerned about securing his northern and eastern borders running in an arc from the Spanish Netherlands along the Rhine River to the Swiss border. He also was determined to check the power of the Hapsburg Emperors and to secure his southern border with Spain. Louis’ pursuit of French glory alarmed his neighbors and led them to form coalition after coalition to break his power. The early wars of Louis XIV included struggles with the Netherlands (or Holland, called in the text the United Netherlands) and with Spain. In 1667, his armies invaded Flanders (modern Belgium) and the Franche-Comté (in Eastern France near the Swiss border) but he was repulsed by a triple alliance of England, Sweden and the Netherlands. Nevertheless by the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1668), Louis gained control of some towns bordering the Spanish Netherlands. In 1670 (as we saw), he signed a secret treaty with Charles II of England, the Treaty of Dover, which made England and France allies against the Netherlands. Louis again invaded the Netherlands in 1672 and seemed to be winning until the Stadtholder and future king of England, William III, forged an alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor, Spain, Lorraine and Brandenburg who all considered Louis XIV a threat to both Catholic and Protestant Europe. The fighting was inconclusive and the war ended in 1679 with the Peace of Nijmegen in which Louis did gain some territory including Franche-Comté. Louis XIV’s Religious Policies Although Louis’ policies were not oppressive in the lives of the French people, he did believe (like Richelieu) that political and religious stability required religious conformity and so he suppressed both dissident Catholics (the Jansenists whom we shall soon meet) and Protestants (the Huguenots) who – as far as Louis was concerned were a threat to political unity. 9 Suppression of the Jansenists As we have seen, the kings of France and the French church had long guarded their ecclesiastical independence (or Gallican Liberties – Gallican comes from Gallia, the old Roman name for France) from papal domination. But after the conversion of Henry IV to Roman Catholicism in 1593, the pro-papal Jesuits were given a monopoly in the education of upper-class Frenchmen. Even before the 1630s, they immersed upper class gentry in the doctrines of the Council of Trent. The Jesuits and their students – even Henry IV, Louis XIII and Louis XIV – thus came to clash with a powerful and growing religious movement called Jansenism. The founder of the Jansenist movement was Cornelius Jansen (d. 1638), who was a Flemish theologian and bishop of Ypres. Influenced by French Huguenots, Jansenism echoed the Augustinian and Calvinist traditions in that it emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. Jansen’s posthumous publication, Augustinus, assailed the Jesuits and taught that men and women had been so corrupted by original sin that they could not contribute anything to their own salvation. After Jansen’s death, the movement began to grow and became centered in the Parisian convent of Port Royal (in Paris). Although deeply pious and loyally Catholic, Jansenists were - like the Calvinists and the English puritans – serious, morally austere and uncompromising - and were particularly at variance with the Jesuit teachings about free will. Jansenism quickly attracted many prominent families in Paris which were opposed to the Jesuits. In 1653, Pope Innocent X declared the Five Jansenist Theological Propositions heretical. Simplified, they are: 1, that there are some commands of God which human beings simply cannot keep, no matter how hard they try; 2, that it is impossible for fallen man to resist God’s grace; 3, that human beings lack free will; 4, that grace is necessary for all interior acts, including faith; and 5, that it is false to say that Christ died for all. In 1656, the pope banned Jansen’s Augustinus. In 1660, Louis rigorously enforced a papal bull banning Jansenism. He closed down the Port Royal Convent after which Jansenists either retracted their views or went underground. By suppressing the Jansenists, Louis XIV ceased defending Galician Liberties and created within the French church a core of opposition that would haunt Louis’ successors. Revocation of the Edict of Nantes Louis also turned his attention to the Huguenots. Ever since the Edict of Nantes (issued by Henry IV in 1598), relations between the Catholics (who constituted 90% of the French population) and the Huguenot minority remained hostile. By the 1660s, the Huguenot population was in decline and the French Catholic Church supported their persecution as both pious and patriotic. After the Peace of Nijmwegen, Louis rigidly persecuted the Huguenots. He was influenced by his mistress (who secretly became his second wife after his first wife died) Madame de Maintenon (1635-1719) who was a devout Catholic and drew the middle aged Louis more towards religious observances. Louis hounded Huguenots out of public life and banned them from government positions and professions such as printing and medicine. He even used financial incentives to lure them to convert and bullied them by quartering troops in their towns. Finally in1685, Louis issued a revocation of the Edict of Nantes which was followed by harsh persecution. He exiled Huguenot ministers, closed their churches and schools and sent non-converting laity to be galley slaves – then taking their children and raising them Catholic. The revocation was an enormous blunder as Protestants everywhere came to think of Louis as a fanatic who must be resisted at all costs. Louis actually believed that this was his most pious act for the Church. The revocation also crippled France economically as more than 250,000 people (most of them highly skilled professionals) fled and formed communities abroad, joining resistance movements to Louis in England, Germany, the Netherlands and the New World. 10 Louis’ Later Wars The Nine Years’ War: After the Treaty of Nijmwegen in 1679, Louis used his powerful army to try to gain more territory. In 1681, he occupied the free city of Strasbourg on the Rhine River which caused a new coalition, the League of Augsburg, to form against him. The league included England, Spain, Sweden, the Netherlands and many German states – including Hapsburg Emperor Leopold I (r. 1658-1705). For nine years (1689-1697) the coalition battled Louis on the continent and in North America where England and France battled each other in King William’s War (named for William III of England who reigned from 1688-1702). The war ended in September 1697, with the Peace of Ryswick which guaranteed the Netherland’s borders and blocked Louis’ expansion into Germany. The War of the Spanish Succession On November 1, 1700, the last Hapsburg king of Spain, Charles II (r. 1665-1700), died childless. Even before his death, the major European powers, fearing the instability of a power vacuum, began diplomatic negotiations to divide his kingdom (remember that he was king of Naples and the Spanish Netherlands – and controlled an enormous empire in the Americas and the Philippines) in order to preserve the balance of power. The cause of war was that in his will, Charles II made his heir the grandson of Louis XIV, Philip of Anjou, who became Philip V of Spain (r. 1700-1746). The thought of a relative of Louis XIV controlling Spain and its empire terrified most of Europe. A Grand Alliance was formed by England, the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire. Then Louis further angered the Dutch and English by recognizing the Stuart claim to the English throne. The War of the Spanish Succession involved most of Western Europe and in North America was called Queen Anne’s War (named for Queen Anne of Great Britain who reigned from 1702 to 1714). France - for the first time - went to war without adequate finances, a well-equipped army or competent generals. The English in particular had advanced technology (flintlock rifles, paper cartridges and ring bayonets) and had developed superior battlefield tactics (especially more maneuverable troop columns rather than the traditional deep columns). Even though the French had successes in Spain, the English general John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722) defeated Louis’ armies in every engagement. Nevertheless after 1709, the war became a bloody stalemate. Peace came with England and the Dutch by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 and with the Holy Roman Emperor in 1714 by the Treaty of Rastatt. By the terms of the two treaties, Philip V kept Spain but lost his possessions in the Spanish Netherlands and Italy most of which went to the Emperor. [The Spanish Netherlands now becomes the Austrian Netherlands.] England got Gibraltar and Minorca; and Louis was forced to recognize the right of succession of the House of Hanover in England if Anne died without issue [heirs]. France after Louis XIV Louis XIV died in 1715 just a few days short of his seventy-seventh birthday. He had outlived both his son (Louis, le Grand Dauphin) and his grandson (Louis, Duke of Burgundy) and the oldest child of his great grandson (Louis of Brittany). So Louis XIV was succeeded by the Duke of Burgundy’s second son, his five year old great grandson, Louis XV, who reigned from 1715 to 1774. Until he came of age, his uncle, Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (a nephew of Louis XIV) was regent until he died in 1723. At that point Cardinal André-Hercule de Fleury (1653-1743) became regent until 1726 and served Louis as his chief minister until his death in 1743. Although a weakened France possessed Europe’s largest population, an efficient governmental bureaucracy and a strong – even though weakened – economy, the bottom line was that Louis XV inherited a bankrupted France drained by his great grandfather’s wars and lavish spending. 11 The Mississippi Bubble Although the Duke of Orléans, as regent, cut taxation and modestly reduced the size of the army, his highhanded measures caused a rebellion in Brittany which was easily crushed. But he was nevertheless was a gambler and for a time turned over the financial affairs of France to a Scottish mathematician and fellow gambler, John Law. Law believed that an increase in the supply of paper money would stimulate France’s economic recovery. So in 1718, he established the Banque Royale (Royal Bank) in Paris that issued paper money and then organized the Mississippi Company which held a business monopoly in the French colonies in North America and the West Indies. The Mississippi Company also took over management of the French national debt and issued shares of its own stock in exchange for government bonds, which had fallen sharply in value. To redeem large quantities of bonds, Law encouraged speculation in the Mississippi Company stock. In 1719, the value of the stock rose strongly and that was the Mississippi Bubble. The problem was that smarter investors took their profits by selling their stock in exchange for paper money from Law’s bank which they then sought to exchange for gold. But Law’s bank lacked enough gold to redeem all the paper money brought to it. So the bubble burst when investors attempted to convert their paper notes into gold, forcing the bank to stop payment on its paper notes. The Duke of Orléans dismissed John Law from the government and Law soon fled France. The Mississippi Bubble Bust was a fiasco for the government that had sponsored John Law. The Mississippi Company was later reorganized and run profitably, but the fear of paper money and speculation schemes haunted French economic life for decades. The Renewed Authority of the Parlements The Duke of Orléans also attempted to bring the nobility back into the decision making processes of government. On the surface it was a good idea, but the nobility had – after years of idle amusements at Versailles – lost both the desire and talent to govern. But the nobility did not hesitate, on the other hand, to use their renewed role in government to limit the power of the monarchy. And they hampered the king through the old institution of Parlements, or courts which they dominated. The Duke of Orléans also returned more power to the Parlement of Paris to confirm or disallow laws. And that action set a precedent that lasted until the French Revolution that Parlements became more independent and an impediment to royal authority. Louis XIV worked with and dominated the Parlements, but, thanks to the Duke of Orléans, both Louis XV and his minister Cardinal Fleury were forced to work against the growing power of the Parlements. Cardinal Fleury was in many ways comparable to Sir Robert Walpole in Great Britain. Although Walpole guided Britain into constitutional government and Fleury worked to maintain the authority of the king, they both pursued economic prosperity at home and peace abroad. But in two chapters we shall see that neither was able to avoid a series of wars beginning in 1740. Central and Eastern Europe Central and Eastern Europe were much less economically advanced than Western Europe. Except for the ports along Baltic (the old Hanseatic League), their economies were almost completely agrarian. That meant fewer cities and more large estates with more serfs working the land. During the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, these areas east of the Elbe River were slowly learning to imitate French Absolutism. But before we look at the big three - Austria, Prussia and Russia - we need to look at Poland. 12 Poland Poland was a large land that at one time stretched from the Baltic to the Ukraine. We saw how in 1683, King John Sobieski (r. 1674-1696) led an army to help lift the siege of Vienna. But after that, Poland became a decentralized nation, dominated by the aristocracy and a growing prey for the big three: Austria, Prussia and Russia. The Polish kings were elected and so were dominated by the nobility. Worse still was the fact that Poland had a legislature, the Sejm (diet), which included only the nobility - not leaders from towns and cities. Moreover the Sejm was crippled a procedural rule, the Librum Veto, which made any legislation impossible without 100% agreement. Thus any single member of the Sejm could “explode the diet;” – often because of foreign or internal bribery - which kept Poland ineffectual and caused Poland to disappear as an independent nation by 1795. The Hapsburg Empire With the retirement of Charles V, the crown of the Holy Roman Empire fell to Charles’ brother Ferdinand. And then when Spain fell into decline after the death of Philip II, it meant that the Austrian Hapsburgs were on their own. Finally after the Treaty of Westphalia 1648, the biggest problem for the Austrian Hapsburgs was that their power base depended not so much on military strength as on their ability to finesse and manipulate the various political entities within the Holy Roman Empire. These included the large states like Saxony, Hanover, Bavaria and Brandenburg as well as the over 350 smaller German cities, bishoprics and principalities. Thus the Hapsburgs had to strengthen their hold on these German states but also expand their influence outside the empire. This was symbolized by a dual kingship in which the Hapsburgs wore both The Crown of St. Wenceslas (encompassing Bohemia [the Czech Republic], Moravia and Silesia - in the empire) and the Crown of St. Stephen (encompassing Croatia, Hungary and Transylvania - outside the empire.) After the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, Austrian power was based more outside the Empire (now it had Italian and Belgian satellites) than inside it where the Hapsburgs needed the cooperation of the local nobility. The result was a decentralized power base, which was a geographically and ethnically diverse empire of many different languages, customs and religions. Even the dominant Roman Catholicism failed to knit the empire together, especially in Hungary where the Magyar nobility were predominately Calvinist. Thus the Hapsburgs learned to rule through regional councils that helped create common objectives for the various parts of the empire. But what they lacked was centralized authority which would make these regional councils unnecessary. It is therefore astounding that the Emperor Leopold I (r. 1658-1705) was not only able to halt the military advances of the Ottomans (which culminated in the Siege of Vienna in 1683) but also resist the military advances of Louis XIV. By the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, Leopold forced the Ottomans to recognize his sovereignty over Hungary and he soon extended his authority over much of the Balkans. He also gained access to the Mediterranean Sea via the Adriatic port city of Trieste which opened new opportunities for trade - and compensated for the loss of political authority in Germany. Leopold was succeeded by his eldest son Joseph I (r. 1705-1711) who continued Leopold’s policies. Joseph was succeeded by his younger brother Charles VI (r. 1711-1740) who also continued these policies but soon came to face a new problem. Like Henry VIII of England, he was not able to sire a male heir and he feared very much the instability (internal and external), if his daughter, Maria Theresa, should succeed him. So he worked for the approval of his family and the various rulers (big and small) to recognize what he called the Pragmatic Sanction, which would legalize female succession. Everyone agreed or were paid off and Maria Theresa succeeded her father. Nevertheless, Charles failed to leave his daughter a strong army and one foreign ruler, Frederick II of Prussia, would invade the Hapsburg domains two months after Charles’ death and seize the province of Silesia - precipitating the War of the Austrian Succession. 13 The Rise of Prussia After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 which ended the Thirty Years’ War, northern Germany was the scene of the spectacular rise of Prussia and the Hohenzollern family which had ruled Brandenburg since 1417. Through inheritance, the Hohenzollerns acquired Cleves, Regensburg and Magdeburg by 1614. In 1618, they acquired East Prussia and in 1648, Pomerania. Except for Pomerania, none of these lands shared a border with Brandenburg, but these acquisitions gave Brandenburg-Prussia a large – albeit (although) scattered - kingdom stretching from East Prussia inside Poland to Cleves near the Dutch border. The Hohenzollerns faced daunting challenges. First, most of their lands lacked natural resources and second, many of the territories which they controlled were still recovering from the devastation of the Thirty Year’s War. The person who began to forge the modern Prussian state was the Elector of Brandenburg, Frederick William (r. 1640-1688), called the Great Elector. He centralized authority by weakening the power of the local nobility, organizing an efficient bureaucracy (government) and laying the foundation for one of the finest armies (albeit still small) in all of Europe. Frederick William was Lutheran and he found competent bureaucrats by welcoming Protestant refugees from France. Between 1655 and 1660, his lands were threatened when Sweden and Poland fought each other crisscrossing his territories. Frederick realized he needed money but was denied new taxes by the Brandenburg Estates (the General Assembly); so he simply ignored the Estates and collected the money he needed by force until he had enough money to build an army strong enough to enforce his will with or without the agreement of the nobility. Then he lost no time using his army to force the nobility to obey him in his scattered domains. Nevertheless, Frederick knew that he had to finesse his nobility. So in exchange for their loyalty, Frederick allowed the noble landlords, or Junkers, more power over their serfs. He also chose for his bureaucrats and local administrators, men of noble extraction or men from the up and coming middle class. All these officials were required to swear a personal oath of loyalty to the Elector and these relationships made Prussia a united, powerful state. In 1688, the Great Elector died and was succeeded by his son, Frederick I (r. 1688-1713), who was a man of many accomplishments. Frederick was the least Prussian of the Prussian kings (i.e., noted for frugality and hard work). He built palaces, founded Halle University (1694), patronized the arts and lived luxuriously. In the War of the Spanish Succession, he put his army at the disposal of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, who in exchange gave Frederick the much coveted title, King of Prussia in 1701. He was succeeded by his son Frederick William I (r. 1713-1740) who was one of the most eccentric and yet “Prussian” (i.e., hardworking and efficient) of all the Hohenzollern rulers. Frederick William I encouraged farming, reclaimed marshes; stored grain in good times (selling it for profit in bad times); he organized his bureaucracy along military lines and instilled in it and in the army a discipline that was fanatical. He doubled the size of the army, making it the third or fourth largest – and the most efficient – in Europe; an astounding feat since Prussia ranked thirteenth in population in Europe. Frederick William had separate laws for the military and for civilians and the officer corps was the elite of the social classes. The Junkers dominated the officer corps forming a tradition that lasted until the end of World War II. William’s military priorities dominated government, society and daily life as in no other European state. It was said that whereas other states possessed armies, the Prussian army possessed a state. 14 Because of his ruthlessly efficient methods, Frederick William I amassed a huge financial surplus and even though he used it to create the finest army in Europe and made it a symbol of Prussian military power, he never used his army as an instrument of foreign wars or aggression. At his death in 1740, his son, Frederick II (better known as Frederick the Great) came to the throne and quickly used both financial surplus and the army to make Prussia a first rate European power: in two astounding wars won by his personal daring and outright luck: The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Russia looks to the West After Kiev fell to the Mongols, it was the Russians in the forests north of the steppes [extensive grasslands south of the great forests] that began to fill the power vacuum and resist the Mongols. At first they paid tribute to the Mongol khans but, Ivan III or Ivan the Great (r.1462-1505) took a daring gamble; he stopped paying tribute to the Mongol Khan in 1476. This defiance of a Khan too weak to enforce obedience marked the beginning of the Gathering in of the Russian Land. Ivan continued this policy and molded Moscow into a strong, centralized state. Ivan’s most important acquisition was in 1471 when he absorbed the important trading city of Novgorod (a hub for the fur trade and a member of the Hanseatic League). Ivan married Sophia Paleologus, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor and took his inspiration from the Byzantine Empire and considered himself their heir, so that just as Constantinople was the Second Rome, so Moscow was the Third Rome. Ivan III’s grandson, the enigmatic Ivan IV took the title Tsar (or Caesar) but he had a troubled reign. When Ivan died in 1584, he left no capable heir. (He had personally killed his oldest son, Ivan, in a fit of anger) Another son Feodor became tsar, but was incompetent and turned over daily rule to his brother-in-law Boris Godunov, who, after Feydor’s death in 1598, was made tsar. At first, Gudonov was popular and ruled well. He anticipated Peter’s the Great’s desire to catch up with the west and was the first tsar to import foreign teachers. But his paranoia led to persecutions of the Boyars and political instability. Then Russia fell into a terrible civil war, which helped bring a terrible famine. Poland and Sweden took advantage and invaded Russian territory. This so-called “Time of Troubles” lasted fifteen awful years from 1598 to 1613. An uprising led by two pretenders, both claiming to be the dead Tsar’s murdered son, added to the disorder. In 1610, when Polish and Swedish armies invaded Russia, volunteer armies rallied to expel the invaders. An assembly of Boyars then selected Mikhail Romanov, a young relative of Ivan IV’s first wife, as the new Tsar who ruled from 1613 to 1645. He finished the expulsion of Swedish and Polish military forces, restored a shattered and demoralized Moscow and began to reestablish centralized authority. One of his greatest accomplishments was to replace corrupt Boyars who held governmental posts with competent administrators. Mikhail’s son and successor, Alexis Romanov (1645 – 1676), continued to strengthen the Tsar’s authority. Alexis abolished the assemblies of the Boyars and managed to acquire Kiev and the Ukraine. [As a point of interest: When Charles I of England was beheaded by the Parliamentarians under Oliver Cromwell in 1649, an outraged Alexis broke off diplomatic relations with England and welcomed Royalist refugees in Moscow.] The establishment of the Romanovs brought the problem of succession to an end but did not bring political stability. The biggest problem facing Russia was the question of westernization and technology. The Tsars were more and more aware that Western European countries were seeped in the Enlightenment and were continuing to develop economies, technologies and political organizations that far outstripped their own. 15 But awareness and action are always two different realities. Opposition would come from the Boyars, who were the landed nobility, along with merchants and many church officials who all opposed westernization. So the question became: how to transform Russia from an agricultural, multicultural and decentralized country into an industrialized, centralized and modernized Empire that looked to forward not backward. The solution – such as it was – would come from Peter the Great. In 1682 the grandson of Mikhail Romanov, Peter I (Peter the Great), became czar and reigned until 1725. To say he was remarkable is an understatement because he carried out a policy of modernization and expansion that aggressively tried to transform Russia from a decentralized, agricultural state into a three billion acre Russian Empire - and thereby make Russia a major European power. At first, he was forced to reign with Ivan, a sickly, older half-brother with his older, half-sister Sophia as regent. In 1689, just as Peter came of age, Sophia tried to launch a coup against him, but Peter pushed her aside (confining her to a convent) and took full power. Ivan “conveniently” died in 1695. As a boy, Peter spent much time in a place in Moscow called Germantown, which was home to thousands of German traders and craftsmen. Spending time among these Germans, Peter became fascinated with their advanced knowledge of technology, especially military tactics, siege craft and shipbuilding. The young future-tsar quickly grasped the importance of science and western learning and what it could do for Russia. He knew that if Russia were to compete with Europe, it would have to catch up and come out of its medieval lethargy and cultural insularity [isolation]. After taking the throne, Peter instituted a policy of forced and rapid modernization. He sent Russians abroad to learn in European countries and he himself went (in disguise) on his own tour of Germany, the Netherlands, and England to learn about Western industrial and military technology. 1. Peter reformed the army by offering better pay and drafting peasants to serve for life as professional soldiers. He provided his soldiers with better training and modern European weapons. He demanded his officers (aristocracy) study geometry so as to use artillery effectively. By his death he had built the largest army in Europe which proved its worth by defeating Sweden in the Great Northern War, which lasted 22 years. Peter was also determined to build a modern navy, which could dominate the Baltic Sea. 2. Peter overhauled the government bureaucracy to make it more efficient in tax collecting and industrial output. Because Russia had few major cities and was an agrarian land, he required the nobles to serve as government officials. He established the Table of Ranks, in which officials advanced through 14 levels of bureaucracy according to merit, not hereditary privilege. He underscored the duty of citizens to serve the state and set the example of himself as an energetic servant, not a privileged parasite [a person who exploits the hospitality of the rich and earns welcome by flattery], thus making an abstract political concept a political reality. 3. Socially: Peter intended to bring Russia out of its cultural dark ages. He abolished the Terem (harem), which kept upper class women secluded from men outside their own families. Peter demanded social mixing of the sexes, especially in cities and towns. He also required Boyar men to shave their beards and wear Western clothing. The conservative nobility resisted Peter’s reforms and Peter got into their faces, so to speak, and personally shaved men’s beards. By sheer force of will and offering to let men pay a tax to keep their beards, he either got his way or made money. Peter also simplified the Russian alphabet, established technical schools and reformed the calendar. Peter reformed the Russian Orthodox Church, taking away much power from the patriarch and forbidding men to become monks before the age of fifty (so they could be useful servants of the state). Soon after the Great Northern War, he was titled the Great, Father of His Country, Emperor of All the Russias. 16 But his greatest westernizing policy was the city of St. Petersburg, his “Window to the West” and new capital, which he began to build in 1702 on the Baltic Sea. The city rose near the site of a Swedish fort captured during the Great Northern War and named after his patron saint. It cost thousands of serf’s lives to build and the city so was later called “the city built on bones.” Yet the city provided a haven for Russia’s new navy and offered access to western European lands through the Baltic Sea. Peter made St. Petersburg the center of an efficient government. He literally moved the government into new buildings, in a city designed by Italian architects. After Peter, Russia had two capitals: Moscow in the Russian heartland and his new administrative capital, Saint Petersburg, home of the tsars on the Baltic. Peter the Great and his son Aleksey had a difficult and torturous relationship and Peter disapproved of his son because Aleksey never demonstrated the intellect or ambition Peter considered essential for his heir. By 1716, Peter was convinced that his son was the focus of treasonous elements against him. Then the next year, Aleksey traveled to Vienna where he appears to have entered into a conspiracy against his father with Charles VI of Austria. When Aleksey returned home he was “investigated” by Peter who became convinced his son was a source of danger to him and when Peter did uncover evidence of an Aleksey-Charles VI plot, Aleksey was arrested, condemned to death but died under mysterious circumstances before the execution. Thus Peter was succeeded by his wife, Catherine I, the first woman to reign as Tsarina of Russia. She continued the westernization policies of her husband, worked well with government ministers and reduced many of the burdens on the peasants, earning her a reputation among the peasants as just and fair. She died in 1727 and was succeeded by Peter II, the fourteen year old son of Peter the Great’s son, Aleksey. Peter II “ruled” two years and died of smallpox in 1730 and was succeeded by Anna, a niece of Peter the Great. She died in 1740 and was succeeded by Ivan IV, an infant and her grandnephew. He was replaced that same year by Elizabeth, (1741–1762), a daughter of Peter the Great who vigorously led her country into the War of Austrian Succession and the Seven Years' War. Elizabeth was succeeded by her nephew, Peter III, who was an admirer of the Prussian military. He immediately withdrew Russia’s support from the war and allowed Frederick the Great to win the war. A few weeks later he was assassinated and succeeded by the most able of Peter the Great’s successors, Catherine II, better known to history as Catherine the Great. The Ottoman Empire As the Byzantine Empire began to crumble in Asia Minor after their terrible defeat at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, large numbers of nomadic Turks migrated from Central Asia to Southwest Asia. The leader of one of these groups was a Turk named Osman, who in the late 1200s and early 1300s, carved out a small state in Northwestern Anatolia – at Byzantine expense. In 1326 the Ottomans captured Bursa, which became their capital in Anatolia. During the 1350s, the Ottomans crossed the Dardanelles on the Balkan Peninsula. By 1365 they made Edirne (the old Greco/Roman city of Adrianople, in modern Bulgaria) their second capital. But what they really wanted was the big prize: Constantinople! The Ottomans created a formidable military machine. Ghazi recruits were originally divided into light cavalry and volunteer infantry supplemented by a professional cavalry equipped with heavy armor. But their strongest military group came from an unusual source. In conquered territories, especially in Europe, the Turks created the Devshirme, which required Christians to contribute young boys to become slaves of the sultan. The boys received special training and were converted to fanatical Islam. The brighter ones entered Ottoman civil administration, but most became famous as Janissaries (Turkish for new troops). The Janissaries quickly became the elite warriors of the Ottoman armies, noted for their esprit de corps (powerful devotion to the group), loyalty to the sultan, and their ability to employ new military technologies (gunpowder weapons) with devastating military effectiveness. 17 Thus by 1400, the Ottoman Turks were closing in on Constantinople, but were blunted in 1402 when the Mongol adventurer, Tamerlane, smashed their army and set their efforts back for a generation. But by the 1440s the Ottomans had recovered and began again to encroach on what was left of Byzantium and encircle the capital at Constantinople. In 1451, a new sultan, Mehmed II (Mehmed the Conqueror) came to power and immediately attacked the city which fell in 1453. Mehmed appreciated the city’s location and history and made it his capital, naming it Istanbul. Under his successors the Ottoman Empire continued to expand. His son Bayezid II (the Just, 1481 – 1512) attacked the last Venetian outposts in Greece. He was patron of both western and eastern culture and worked hard to ensure a smooth running of domestic politics. His son, Selim the Grim (1512 – 1520, Grim in the sense of brave), defeated the Safavid Persians in 1514 at Chaldrin, and then captured Syria, Mamluke Egypt, Mecca, Medina and Yemen. The Ottomans reached their high point under Suleyman the Magnificent (1520-1566). In 1521, he attacked AustriaHungary and captured Belgrade. In 1526, he defeated and killed the king of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács. In 1529, he (aided by Francis I of France) laid siege to Vienna, but failed to take it. In the Ottoman Empire, conquered peoples or Dhimmi, were usually protected and could maintain their religious autonomy in special communities. So long as the Dhimmi gave loyalty and paid the Jizya (or head tax charged to all non Muslims) to the sultan, they retained their personal freedom, kept their property, and were able to practice their own religion and handle their own legal affairs. In the Ottoman Empire this was called the Millet System. When the Ottomans were strong, the Millet System was an easy way to loosely administer conquered peoples, but when they began to decline, the Millet System meant that the ethnic Christians already had the beginnings of a governmental apparatus (mechanism). In the 19th century and the rise of Nationalism, each millet became increasingly independent and began to establish their own schools, churches, hospitals and other facilities which effectively undermined Ottoman authority. The eighteenth century saw the authority of the Ottomans rapidly decline and they became known as the “Sick Man of Europe.” The causes were many, convoluted and complicated. But four explanations summarize the impending doom which would befall the Ottomans: 1. First, the Sultan and his bureaucracy became lazy, incompetent and corrupt. 2. Revenues declined due to inflation (remember that Spanish New World Silver) and the Europeans were bypassing the old Silk Road trading routes with their ocean trading routes. 3. Local officials began to carve out their own fiefdoms, withholding income and inciting peasants to numerous, destructive rebellions. 4. The Janissaries became strong and influential while the regular military forces – free peasants – were frozen out of the army, thus creating an almost mercenary army, which cost more and became more and more inefficient. Even with mounting problems the Ottomans made one last major offensive against Europe. In 1683 they besieged Vienna, which was saved at the last desperate minute by allied forces, especially those of King Jon Sobieski of Poland. This failure marked a turning point in world history because now the Austrians and Russians began to take more and more European territory back from Ottoman control. And as we have seen, in 1699 by the Treaty of Karlowitz, the Ottomans were forced to surrender most of Hungary to the Hapsburgs. Following that, the Sick Man of Europe just got sicker. 18