Voice Paper 2 full version - You have reached the Pure environment

advertisement

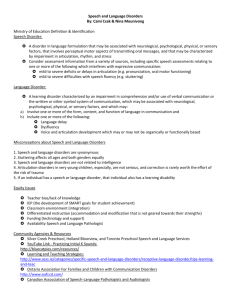

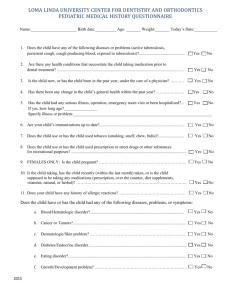

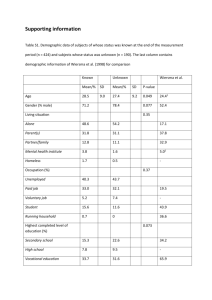

Development of a minimum protocol for assessment in the paediatric voice clinic. Part 2: subjective measurement of symptoms of voice disorder. Dr Wendy Cohen, Miss Amanda Wardrop and Dr Elspeth McCartney Speech and Language Therapy School of Psychological Sciences and Health University of Strathclyde 76 Southbrae Drive Glasgow G13 1PP Email: wendy.cohen@strath.ac.uk Tel: + 44 141 950 3450 Mr Haytham Kubba and Mr David Wynne ENT Department Royal Hospital for Sick Children Dalnair Street Glasgow G3 8SJ Development of a minimum protocol for assessment in the paediatric voice clinic. Part 2: subjective measurement of symptoms of voice disorder. Abstract The ELS recommend that functional assessment of voice disorder in adults requires evaluation of a number of different parameters. These include perceptual evaluation of voice, videostroboscopic imaging of vocal fold movement, acoustic analysis of specific voicing aspects, aerodynamic support for voicing and a subjective rating of voice impact. No specific guidelines are available for children, but a similar range of parameters is needed to guide intervention and measure outcomes. The development of subjective voice measures for adults and their adaptations for the paediatric population are reviewed and compared to the research comparing these to evaluation of vocal function. The need for further refinement of child assessment measures, and a proposal of how these might be developed, is discussed. Introduction In the UK, children are normally referred to hospital ear, nose and throat (ENT) clinics by a general practitioner (GP) seeking assessment. Assessment of patients wtih voice disorders takes place in the voice clinic. From here, patients may undergo surgical intervention and/or speech and language therapy (SLT), which is often in the community setting. As outlined in a companion paper1 , evaluation of vocal function in children can, and should, include the perceptual, videostroboscopy, acoustic and aerodymanic parameters. The European Laryngological Society (ELS) recommends minimum measurement for each of these parameters in addition to subjective measurement of the impact of voice disorder2. This is in line with WHO guidance3 where assessment should include both measures of vocal function and of the effects of dysfunction on the child’s activity/participation in society and quality of life (QOL). This would involve determining at least the child’s and their parents’/carers’ perceptions of the impact of voice disorder. It is important to get views from both perspectives, as there are differences between parent / carer perceptions and those of their children 4 and both perspectives are valuable. The identification and management of paediatric voice disorders is important for the child’s educational and psychosocial development, as well as physical and emotional health. The fundamental cause of any voice disorder must be established because voice disorders that have similar symptoms may have extremely different behavioural, medical or psychosocial aetiologies5. Reciprocally, similar pathologies can result in widely different symptoms and clients with comparable voice disorders often experience contradictory levels of impact6. Subjective measurement of impact produces clinical information aiming to improve the medical and psychological care of children and adolescents with voice disorders. Fortunately, many children and adolescents can provide personal and reliable information about the impact a voice disorder has on their own activity/participation and QOL and it is important to encourage the consideration of these outcomes to help tailor individualised holistic interventions for children and adolescents7. The PedsQLTM 8provides a psychometrically validated tool for measurement of quality of life that can be used in children from 8 years, though the content of the scales are less relevant for the specific issues relating to the impact of voice disorder. Furthermore there are very few child measures available with good enough psychometric properties to allow them to be used in ENT and SLT diagnostic clinics. Insights from adult measurement of voice must be therefore be sought. One of the conclusions drawn from the companion paper to this is that further research is necessary exploring the relationship amongst the five ELS vocal parameters in children, and whether each adds clinically useful information. The current paper reviews relevant research that has explored the relationship between assessment of vocal function and subjective rating in adults with voice disorder and considers the extent to which these findings relate to children with voice disorder. The paper goes on to review current tools used for subjective rating of the impact of voice disorder in adults, and the small number available for children. The limitations of child measures are discussed in relation to their adaptation from adult based questionnaires, rather than identifying child-specific factors, and the fact that they ask only for parental views. Parent views are important in their own right, but must be supplemented where possible with the child’s own; especially where there may be discrepancies between parental proxy reporting and children self reporting in relation to QOL scales9. Recent research 4 10 has made steps towards addressing these limitations. The paper concludes by discussing implications for children with voice disorder, and outlines the research needs in relationship to developing a psychometrically sound subjective rating measure for children. Comparing subjective assessment of impact on activity/ participation and quality of life with assessment of vocal function: the need for separate measurement. Studies have compared adult perceptual evaluation of voice with subjective scales in order to investigate whether increased severity of dysphonia equates with decreased quality of life. Some 11 find the relationship to be moderate and others12 find it to be relatively weak. The differences reported may be related to different evaluation tools. Of interest from these studies is the assertion that clinical assumptions made from perceptual analysis do not necessarily match up with the patient’s own subjective rating of impact. It is important therefore that any decisions made regarding intervention should be made with this in mind. Fewer studies have explored acoustic analysis of voice with subjective self rating. Wheeler and colleagues13 compared a variety of acoustic measures (FO, jitter, shimmer, and signal-tonoise ratio) from a sustained /a/ together with mean and standard deviation of FO during a reading passage in 17 patients with dysphonia with overall VHI score. The results of this small study did not indicate a relationship between the acoustic measures and scores relating to impact using the Voice Handicap Index (VHI) 6 questionnaire. Studies such as these illustrate that decisions about intervention cannot be made simply on the basis of evaluation of vocal function. Clinical evaluation of adults presenting with voice disorder now routinely incorporates subjective rating questionnaires. The extents to which these same conclusions can be reached in children with voice disorder are yet to be established. A significant problem in this regard relates to how to gather subjective rating of the impact of voice disorder on children. The development of instruments gathering subjective rating of the impact of voice disorder on activity/participation and quality of life Adult measures Substantial progress has been made in evaluating the subjective impact of voice disorder on adults, with the following measures available: Voice Outcome Survey (VOS)14, the VRQOL15, the VHI6, The Voice Performance Questionnaire (VPQ)16 and the Voice Symptom Scale (VoiSS17). The VHI, VOS and V-RQOL were developed in the United States while the VPQ and the VoiSS in the United Kingdom. The VOS has been validated in relation to measuring outcomes following surgery for unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The brevity of the VOS makes it simple to administer and to score, however it does not distinguish subcategories, for example physical and emotional components that contribute to an individual’s QOL18 and this may be related to its specific development as an outcome tool for one organic vocal pathology. The V-RQOL has been validated in a group of 109 adults with voice disorder. Scores from 10 questions are derived for domains relating to physical functioning and social-emotional components of quality of life. It is reasonably quick to score following the algorithms related to the defined question categories. The 12 item VPQ asks patients to provide answers relating to severity of vocal performance through questions designed to elicit information about the physical symptoms and socioeconomic impact of the voice disorder. This notion of expressing the severity of vocal symptoms adds to the information that can be usefully used clinically in providing support and treatment for a voice disorder. The VHI and the VoiSS explore the extent to which voice related symptoms impact on activity/participation and quality of life. The VHI is split into three sub-domains – functional, physical and emotional, each containing 10 questions which have subsequently been reduced to 10 questions in total – five from the functional scale, three from the physical scale and two from the emotional scale19. Internal consistency has been demonstrated between the VHI 10 and the VPQ establishing their value as measures of severity of voice disorder20. Similar to the VHI, the VoiSS is split into three domains: impairment (15 items), emotional (8 items) and related physical (7 items) in addition to a total score. Research has found the each of these tools to be reliable and valid instruments for subjective measurement of the impact of voice disorder21. All consider aspects of impairment or function with the VoiSS also evaluating the impact of associated physical symptoms. These tools having derived from adult case histories and/or surveys, report symptoms, and contain a number of questions about what actually happens as a result of voice impairments. The activities and social participation examples to which these relate will almost certainly be different between adults and children22: employment versus school, friends versus relatives etc. Many questions relate to symptoms, rather than the impact of symptoms or the client’s reaction to them. In identifying the impact of voice disorder in children, it is likely that they and their parents will also wish to evidence specific examples of situations where the voice impairment affects interactions, but children should also be invited to report their subjective reactions to communication difficulty. Child measures A few instruments have been developed to address the impact of voice disorders for children, on the whole derived from measures developed to serve the adult population by adapting questions to child communication contexts. They seek responses from parents or SLTs. Measures derived from adult voice impact questionnaires include the paediatric VOS (PVOS)23, the paediatric V-RQOL (PV-RQOL)24 and the paediatric VHI (PVHI)25. As with the VOS, the PVOS relates specifically to unilateral vocal fold paralysis and incorporates surgical outcomes for this in addition to velopharyngeal incompetency. The scale is completed by parents. The PV-RQOL uses the same items 10 items as the V-RQOL, with wording presentation altered from the adult to a parent proxy version. Scores are associated with the rating scale (ranging from “not a problem” to “problem is ‘as bad as it can be’”) with an additional unscored rating where the item is deemed not applicable to the child. Higher values indicate a better quality of life. As with the V-RQOL, there are two domains evaluating socialemotional factors and physical functioning factors. The PV-RQOL has been validated in a group of 120 parents of children with a variety of otolaryngological problems24 and was found to have excellent internal consistency and validity evidenced by a high correlation to PVOS scores obtained from the same parents. Significant differences have been established between children with voice disorder and age matched controls on the PV-RQOL26. The PVRQOL has also been found to be responsive to changes during intervention, differentiating between clients whose voice quality changed during treatment 24. The PVHI was derived from the adult VHI as a proxy questionnaire for parents/carers who rate their child’s overall ‘Talkativeness’, then rate 23 descriptions of functional, physical and emotional aspects of voice on 5-point sub-scales, also totalled. The PVHI was standardised on 45 parents of children aged three to twelve with no history of voice dysfunction, and 33 parents/guardians of dysphonic children aged four to twenty-one awaiting or following laryngo-tracheal reconstruction. Test-retest reliability was established by ten parents of dysphonic children who received no intervening treatment repeating the assessment within three weeks. The PVHI was constructed by eliminating items not relevant to children from the VHI (four from the ‘Emotional’ domain, one from ‘Physical’ and three from ’Functional’). Neither the PV-RQOL nor the PVHI specifically established items that were relevant to activity/participation and quality of life in childhood, drawing only from the adult versions, perhaps a limiting feature. Generic therapy outcome measures, such as the Therapy Outcome Measures (TOMs) published by Enderby, John and Petherham27 provide a pre- and post-therapy measure to reflect changes relating to the WHO-ICF categories of impairment, activity and participation. The added construct Well-being/Distress captures “emotions, feelings, burden of upset, concern and anxiety and level of satisfaction with the condition”27(p18). There are individual TOMs scales for a variety of clinical conditions including voice (see McLeod, McCartney and McCormack28 for a review) however as pointed out by Lubinski, Golper and Frattali29 , outcomes gathered by the SLT providing intervention are open to bias. Moving to child-specific measures In order to develop child-specific measures, the views of children must be sought especially given the fact that parental proxy and child self-reporting may not match9. Ideally, a method that can assess the social, emotional and academic impact of voice disorders on children is a crucial component of a thorough voice evaluation28 and it may be that for effective therapy planning, the impact of the child’s voice quality on peer relations and their ability to function well at school and in other environments should be considered30. Consideration must also be given of children’s emotional and linguistic development when developing a tool that explores impact on activity/participation and QOL. Connor and colleagues4 undertook SLTled interviews with 40 children with a range of voice complaints and their parents. The interview structure was adapted depending on the age of the participants, with children in the youngest age group interviewed with their parent/carer and the older three age ranges interviewed independently. Interview questions were conceptualised into three domains: physical, social/functional and emotional. Themes relating to the physical domain related to, for example, being heard, being able to sing, having a sore throat and running out of air. Social/functional themes related to, for example, their voice being different from their peers, social exclusion, issues around fear of participation. Some emotional themes related to feelings of frustration, embarrassment and low self esteem. The feelings and thoughts of children did not always agree with those of the parents with different issues being raised by different age groups. In one cited example, the presence of organic pathology (vocal fold cyst) and the resultant vocal symptoms was of little concern to the youngster who found removal from class for therapy more troublesome than the presence of vocal pathology. The authors conclude that there is a need for both parents and children to be asked to indicate the impact of their voice disorder, and recommend the need for carefully developed tools to elicit the relevant information at various different ages. Verduyckt and colleagues10 interviewed twenty-five 6-13 year old children with voice disorder and fifty-five control children (aged 5-13yrs) also in the three domains of physical, socio-functional and emotional. Interview data was subject to content analysis and judgements made relating to expression of concern (or not) for a particular item. Significant differences were found between voice disordered and control children on a number of questions within each domain. Children who had already attended for speech and language therapy intervention sessions expressed additional concerns relating to distress with the authors suggesting that by engaging in treatment these children may have become more aware of these feelings. Verduckyt and colleagues corroborate the findings of Connor and colleagues where children expressed more physical domain items while their mothers more emotional domain items. Of note in both of these recent studies is that neither study used adult measures, opting for the systematic use of interview data that allows for children who are emotionally or linguistically less mature to comprehend and respond to the interview questioning. These studies constitute an important step in establishing an instrument for the subjective rating of voice disorders in children, which would be based on their recorded views and perceptions. Research futures Given the potential for differences between parental and child concerns 4 10 and the difficulties for parents of truly reflecting the impact on a child’s internal emotional responses, it is important that new measures should include a subjective rating scale that the child can complete. Consideration must be made as to how children are asked to rate individual responses in relation to their developmental and linguistic capabilities. The Impairment- and Physical-related questions of the VoiSS might be re-written to be answerable by children, and this requires an empirical investigation. Previous research4 10 forms a good starting-point for considering situations where voice impairment might affect a child’s activity and participation. The further issue of determining the impact upon children may also be explored via examination of impact measures developed for children with other speech, language and communication needs, for example the Communication Attitude Test 31 or its preschool counterpart the Kiddycat 32 which is used for children who stammer, as well as by sensitive interviewing of children attending the voice clinic. The view that clinicians should incorporate children’s own reporting of their own perceptions of impact of voice disorder in addition to parental proxy ratings would be consistent with WHO guidance: that assessment should include both measures of vocal function and of the effects of dysfunction on the child’s activity and participation in society (WHO ICF-CY) along with quality of life. Further research is necessary to extend these findings. Conclusion The findings from the studies cited would lend support to the ELS recommendation for subjective rating of the impact voice disorder has on children. The lack of evidence to the contrary suggests that the use of parent proxy rating questionnaires however is insufficient on its own. Further research is required in this area to develop and validate such child reporting tools. Evaluation of outcomes for a child should include assessment of vocal function (as discussed in the companion paper) along with subjective rating of the impact voice disorder has on the child’s activity/participation and QOL. It is clear that further work is needed to add the child’s perceptions of their dysphonia to those of their parents and SLTs. Many children with voice problems are capable of expressing views about their own participation, and how their voice difficulties affect them. They should therefore be encouraged to contribute such information in a manner that can contribute to clinical decision making and outcome evaluation. As indicated previously, there is a need for development and validation of questionnaires that are designed to take account of both parent and child concerns. There is considerable evidence supporting the clinical applicability of the five ELS2 assessment recommendations for functional assessment of voice disorder in children. Comparison and correlation of perceptual, laryngoscopic, acoustic, aerodynamic and subjective rating would add to current knowledge and understanding of this condition and allow for individualised holistic management decisions. Acknowledgements: The authors wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and insightful comments that have been valuable in preparing a revision to this manuscript. Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. References 1Cohen W, McCartney E, Wynne D, Kubba H. Development of a minimum protocol for assessment in the paediatric voice clinic. Part 1: evaluating vocal function. Accepted for publication subject to revisions 2 Dejonckere PH, Bradley P, Clement P, et al. A basic protocol for functional assessment of voice pathology, especially for investigating the efficacy of (phonosurgical) treatments and evaluating new assessment techniques. Guideline elaborated by the Committee of Phoniatrics of the European Laryngological Society (ELS). Eur Arch Otorhinolayngol. 2001;258:77-82. 3 World Health Organisation (WHO Workgroup for development of version of ICF for Children & Youth). (2007). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Children and Youth Version (ICF-CY). Geneva: WHO. 4 Connor NP, Cohen SB, Theis SM, Thiebeault SL, Heatley DG, Bless DM. Attitudes of children with dysphonia. J Voice. 2008;22(2):197-209. 5 Lee L, Stemple JC, Glaze L, Kelchner LN. Clinical Forum: quick screen for voice and supplementary documents for identifying pediatric voice disorders. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2004;35:308–319. 6 Jacobson BH, Johnson A, Grywalski C, Silbergleit A, Jacobson G, Benninger MS, Newman CW. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI) development and validation. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6(3):66-70. 7 Speith LE, Harris CV. Assessment of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: an integrative review. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(2):175-193. 8 Varni JW. The PedsQLTM. Measurement model for the Pediatric Quality of Life InventoryTM.. www.pedsql.org. 9 Creemens J, Eiser C, Blades M. Factors influcencing agreement between child self-report and parent proxy-reports on the pediatric quality of life invetnroy 4.0 (PedsQL) generic core scales. Health Qaul. Life Outcomes. 2006 4:84 10 Verduyckt I, Remacle M, Jamart J, Benderitter C, Morsomme D. Voice-Related Complaints in the Pediatric Population. J Voice. 2011;25(3):373-380. 11 Murry T, Medrado R, Hogikyan N, Aviv JE. The relationship between ratings of voice quality and quality of life measures. J Voice. 2004;18:183-192. 12 Karnell MP, Melton SD, Childes JM, Coleman TC, Dailey SA, Hoffman HT. Reliability of clinician-based (GRBAS and CAPE-V) and patient-based (V-RQOL and IPVI) documentation of voice disorders. J Voice. 2007;21(5):576-590. 13 Wheeler KM, Collins SP, Sapienza CM. The relationship between VHI scores and specific measures of mildly disordered voice production. J Voice. 2006;20:308-317. 14 Gliklich RE, Glovsky RM, Montgomery WW. Validation of a Voice Outcome Survey for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;120(2):153-158. 15 Hogikyan ND, Sethuraman G. Validation of an instrument to measure Voice-Related Quality of Life (V-RQOL). J Voice. 1999;13(4):557-569 16 Carding PN, Horsley IA, Docherty GD. Measuring the effectiveness of voice therapy in a group of forty-five patients withnon-organic dysphonia. J Voice 1999;13:76-113. 17 Deary IJ, Wilson JA, Carding PN, MacKenzie K. VoiSS: a patient-derived Voice Symptom Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54(5):483-489. 18 Gliklich RE, Glovsky RM, Montgomery WW. Voice Quality of Life Instruments. In: Hartnick CJ, Boseley ME. Pediatric Voice Disorders. San Diego: Plural Publishing Inc;2008. p.122. 19 Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, Zullo T, Murry T. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. Laryngoscope. 2004 Sep;114(9):1549-1556. 20 Deary IJ, Webb A, Mackenzie K, Wilson J, Carding PN. Short, self-report voice symptom scales: Psychometric characteristics of the Voice Handicap Index-10 and the Vocal Performance Questionnaire. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2004;131(3): 232-235. 21 Webb AL, Carding PN, Deary IJ, MacKenzie K, Steen IN, Wilson JA. Optimising outcome assessment of voice intervention, I: reliability and validity of three self-reported scales. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 2007;121:763-767. 22 Markham C, van Laar D, Gibbard D, Dean T. Children with speech, language and communication needs: their perceptions of their quality of life. Int J Lang and Com Dis 2009;44(5):748-768. 23 Hartnick CJ. Validation of a pediatric voice quality of life instrument: the pediatric voice outcome survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:919-922. 24 Bosely ME, Cunningham MJ, Volk MS, Hartnick CJ. Validation of the Pediatric VoiceRelated Quality-of-Life Survey. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:717-720. 25 Zur KB, Cotton S, Kelchner L, Baker S, Weinrich B, Lee L. Pediatric Voice Handicap Index (pVHI): a new tool for evaluating paediatric dysphonia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:77-82. 26 Merati AL, Keppel K, Braun NM, Blumin JH, Kerschner JE. Pediatric voice-related quality of life: findings in healthy children and in common laryngeal disorders. Ann. Otolaryngol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2008;117(4):259-62. 27 Enderby, PM, John A, Petherham, B. Therapy Outcome Measures for rehabilitation professionals, speech and language therapy; physiotherapy; occupational therapy; rehabilitation nursing; hearing therapists. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2006. 28 McLeod S, McCartney E, McCormack J. Communication (d310-d369). In: Majnemer A, editor. Measures for children with developmental disabilities framed by the ICF-CY. London: MacKeith Press. In press 2010. 29 Lubinski R, Golper LAC, Frattali CM, editors. Professional issues in speech-language pathology and audiology. 3rd ed. New York: Thomson Delmar Learning; 2007. 30 Baker S, Kelchner L, Weinrich B, Lee L, Willging P, Cotton R, Zur K. Pediatric laryngotracheal stenosis and airway reconstruction: a review of voice outcomes, assessment and treatment issues. J Voice. 2006 Dec;20(4):631-641 31 Brutten GJ, Dunham SL. The communication attitude test: A normative study of grade school children. J Fluency Disorders. 1989;14(5):371-377. 32 Vanryckegham M, Brutten GJ. KiddyCat: Communication Attitude Test for Preschool and Kindergarten Children who Stutter. Plural Publishing Inc; 2006