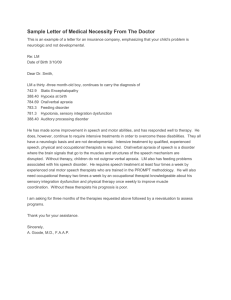

CHRONIC BENIGN INTRACTABLE LOW BACK

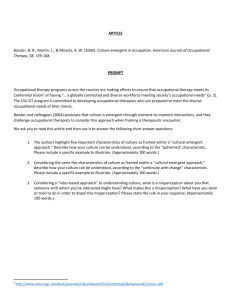

advertisement