Gitlin_et_al_for_BMC_Nephrology_Updated_for_Reviewers

advertisement

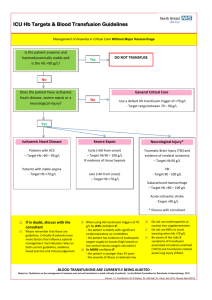

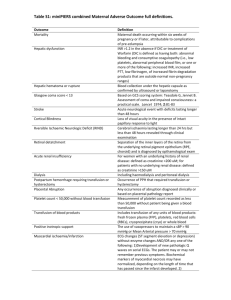

1 Outpatient red blood cell transfusion payments among 2 patients on chronic dialysis 3 4 Matthew Gitlin, PharmD,1 J. Andrew Lee, PhD,1 David M. Spiegel, MD,2 Jeffrey L. Carson, 5 MD,3 Xue Song, PhD,4 Brian S. Custer, PhD,5 Zhun Cao, PhD,4 Katherine A. Cappell, PhD,4 6 Helen V. Varker, BS,4 Shaowei Wan, PhD1 Akhtar Ashfaq, MD1 7 8 1 9 Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ; 4Truven Health Analytics, Cambridge, 10 Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA; 2University of Colorado, Denver, CO; 3UMDNJ-Robert MA; 5Blood Systems Research Institute, San Francisco, CA 11 12 Email addresses: Matthew Gitlin - mgitlin@amgen.com; J. Andrew Lee - juhol@amgen.com; 13 David M. Spiegel - David.Spiegel@ucdenver.edu; Jeffrey L. Carson - carson@umdnj.edu; Xue 14 Song - Xue.Song@truvenhealth.com; Brian S. Custer - bcuster@bloodsystems.org; Zhun Cao - 15 zhun.cao@truvenhealth.com; Katherine A. Cappell, Katherine.cappell@truvenhealth.com; Helen 16 V. Varker - Helen.varker@truvenhealth.com; Shaowei Wan - shaowei.wan@gmail.com; Akhtar 17 Ashfaq - aashfaq@amgen.com 18 19 Corresponding Author: Matthew Gitlin, PharmD, One Amgen Center Drive, Thousand Oaks, 20 CA 91320-1799; Tel: (805) 447-7481; Fax: (805) 376-1847; Email: matthew.gitlin@amgen.com 21 22 Running Head: Transfusion payments in the dialysis setting 23 1 1 Abstract 2 Background: Payments for red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are separate from US Medicare 3 bundled payments for dialysis-related services and medications. Our objective was to examine 4 the economic burden for payers when chronic dialysis patients receive outpatient RBC 5 transfusions. 6 Methods: Using Truven Health MarketScan® data (1/1/02-10/31/10) in this retrospective micro- 7 costing economic analysis, we analyzed data from chronic dialysis patients who underwent at 8 least 1 outpatient RBC transfusion who had at least 6 months of continuous enrollment prior to 9 initial dialysis claim and at least 30 days post-transfusion follow-up. A conceptual model of 10 transfusion-associated resource use based on current literature was employed to estimate 11 outpatient RBC transfusion payments. Total payments per RBC transfusion episode included 12 screening/monitoring (within 3 days), blood acquisition/administration (within 2 days), and 13 associated complications (within 3 days for acute events; up to 45 days for chronic events). 14 Results: 3283 patient transfusion episodes were included; 56.4% were men and 40.9% had 15 Medicare supplemental insurance. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 60.9 (15.0) years, 16 and mean Charlson comorbidity index was 4.3 (2.5). During a mean (SD) follow-up of 495 17 (474) days, patients had a mean 2.2 (3.8) outpatient RBC transfusion episodes. Mean/median 18 (SD) total payment per RBC transfusion episode was $854/$427 ($2,060) with 72.1% 19 attributable to blood acquisition and administration payments. Complication payments ranged 20 from mean (SD) $213 ($168) for delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction to $19,466 ($15,424) 21 for congestive heart failure. 2 1 Conclusions: Payments for outpatient RBC transfusion episodes were driven by blood 2 acquisition and administration payments. While infrequent, transfusion complications increased 3 payments substantially when they occurred. 4 3 1 2 Keywords 3 dialysis; red blood cell transfusions; payers; cost 4 4 1 2 Background Anemia is common in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and results from reduction of 3 erythropoietin production [1]. Prior to the development of pharmacologic treatments for anemia, 4 red blood cell (RBC) transfusions were the mainstay of anemia treatment, and approximately 5 55% to 60% of dialysis patients received RBC transfusions to avoid severe anemia [2-4]. RBC 6 transfusions are associated with a variety of complications, including hemolytic and non- 7 hemolytic transfusion reactions, infections, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), 8 transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), and hyperkalemia [3, 5-11]. In 2009, the 9 rate of RBC transfusion-associated adverse reactions across all disease states was reported as 10 approximately 0.25% [12]. However, the rates of RBC transfusion-related complications may be 11 higher among chronic dialysis patients because of their significant comorbid disease severity and 12 concerns about patients’ fluid overload. Furthermore, while the overall rates of these 13 complications may be low, their outcomes can be severe (hospitalization or death) and their 14 associated costs are high [13-15]. 15 The use of RBC transfusion as a treatment for anemia declined dramatically after the 16 approval of the first erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) in 1989 [16, 17]. In the 1995 annual 17 report of the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), the reported rate of outpatient RBC 18 transfusion in hemodialysis patients dropped from 16% in 1989 to 2% by 1993 [18]. The overall 19 rate of RBC transfusions (per 1000 patient-years) in the hemodialysis setting decreased by about 20 half from 535.33 in 1992 to 263.65 in 2005 [17]. About 83% to 94% of chronic dialysis patients 21 now use an ESA to treat chronic anemia [19]. With the newly implemented Medicare 22 Prospective Payment System (PPS) for ESRD patients, reimbursement to providers is capitated 23 to include dialysis and separately billable medications and services (ie, ESAs, iron, dialysis 5 1 supplies, lab tests) but does not include blood and blood products. Since RBC transfusion use in 2 ESRD patients on dialysis could potentially increase, it is important to understand transfusion- 3 associated payments and outcomes in this patient population. 4 Incomplete accounting of payments related to RBC transfusion administration may 5 provide misleading information to policy makers determining reimbursement policy in a 6 healthcare system such as Medicare. The purpose of this retrospective claims analysis study was 7 to use a micro-costing approach to examine the economic burden for payers when chronic 8 dialysis patients receive outpatient RBC transfusions. This study will assist in quantifying the 9 economic impact to payers of RBC transfusions as they are tracked within many of the PPS 10 surveillance programs and will inform future studies examining RBC transfusion and associated 11 payments in Medicare claims data. 6 1 Methods 2 Data sources 3 The Truven Health MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounter and Medicare 4 Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Databases were used for this study. These databases 5 are constructed from privately insured paid medical and prescription drug claims. The 6 MarketScan Commercial Database contains the inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription 7 drug experience of approximately 30 million employees and their dependents (in 2010) covered 8 under a variety of fee-for-service plans, managed care health plans, and indemnity plans. In 9 addition, the MarketScan Medicare Database contains the healthcare experience of 10 approximately 3.42 million retirees (in 2010) with Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by 11 employers. Medicare-covered portion of payment, employer-paid portion, and patient-paid 12 portion are included in this database. The MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Databases 13 provide detailed cost, use, and outcomes data for healthcare services performed in both inpatient 14 and outpatient settings. The medical claims are linked to outpatient prescription-drug claims and 15 person-level enrollment data through the use of unique enrollee identifiers. All personal 16 identifiers were removed. 17 18 19 Transfusion episode inclusion criteria All analyses in this study were performed at the level of the transfusion episode. Eligible 20 patients were first identified using the following criteria: inclusion in the MarketScan 21 Commercial or Medicare Databases with ≥ 2 claims (to ensure that they were treated for chronic 22 disease) for chronic dialysis ≥ 30 days apart and within 365 days between January 1, 2002, and 23 October 31, 2010 (codes used to identify chronic dialysis claims are listed in Table S1 of the 7 1 Supplemental section); had ≥ 6 months of continuous enrollment prior to first chronic dialysis 2 claim to measure baseline clinical characteristics; had ≥ 1 outpatient RBC blood transfusion on 3 or after date of first chronic dialysis claim through January 31, 2011 (codes used to identify RBC 4 blood transfusion claims are listed in Table S2 of the Supplemental section); had no terminating 5 events (defined as end of continuous enrollment, end of MarketScan® data [January 31, 2011], 6 death, or kidney transplant) between first chronic dialysis claim and first outpatient RBC 7 transfusion; and had ≥ 30 days of continuous enrollment after the first RBC transfusion to 8 identify and measure subsequent RBC transfusion-related complications. RBC transfusions were 9 identified using revenue codes (UB-04), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and Healthcare 10 Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes (codes used to identify transfusion-related 11 complications claims are listed in Table S3 of the Supplemental section). 12 RBC transfusion–related complications that could be identified in the coded dataset and 13 could be reasonably attributed to a transfusion episode (based on medical literature and expert 14 clinical opinion) included febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism, or phlebitis; 15 acute hemolytic transfusion reaction; allergic reaction; TRALI; TACO; delayed hemolytic 16 transfusion reaction; congestive heart failure (CHF); and hyperkalemia. To increase the 17 likelihood that CHF or hyperkalemia complications were directly related to the RBC transfusion 18 episode (rather than a pre-existing condition that coincided with the transfusion), patients with a 19 history of CHF or hyperkalemia during the pre-index period were excluded from the 20 complication cost analyses (but not from overall cost analysis). Because of the short follow-up 21 period post–transfusion episode, we could not collect information on longer-term complications 22 that might require more time to develop or be diagnosed (e.g., transfusion-related infections and 8 1 iron overload). A summary of the patient selection and transfusion episode time frame is 2 presented in Figure 1. 3 4 5 Variable definition and time frame Demographic information was collected on the date of the first chronic dialysis claim. 6 Clinical characteristics were measured during the 180 days prior to the first chronic dialysis 7 claim. Because some patients had multiple RBC transfusion claims within a short time frame, we 8 combined individual claims within 3 days of each other into a transfusion episode, which was the 9 unit of observation for this study. Because pre- and post-transfusion screening and monitoring 10 payments could not be differentiated for patients with more than 1 transfusion claim within an 11 episode, we combined screening and monitoring payments 3 days prior to and 3 days post– 12 transfusion episode. Blood acquisition and administration payments were examined from 13 transfusion episode date to 2 days post–RBC transfusion episode. 14 With the exception of delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions, all complications were 15 identified up to 0 to 3 days post–RBC transfusion episode. Hemolytic transfusion reactions were 16 identified 4 to 45 days post–RBC transfusion episode (Figure 2). If a claim for RBC 17 transfusion–related complication was linked to ≥ 1 RBC transfusion episode, it was linked to the 18 earliest episode. If a claim for a complication could not be linked to an RBC transfusion episode 19 based on the described time windows, the claim was not included in the analyses. 20 21 22 23 Micro-costing/component analysis approach We used a micro-costing approach to measure cost based on the components of resource units and their payment values [20-22]. We included payments for blood acquisition, transfusion 9 1 administration, RBC transfusion–related lab tests, and transfusion complications [22]. For the 2 base-case analysis, we calculated component payments for (1) RBC transfusion screening and 3 monitoring, (2) blood acquisition and administration, and (3) transfusion-related complication, 4 which were summed to calculate (4) total payment for each RBC transfusion episode. 5 We conducted subgroup analyses for (1) patients with an acute bleed or surgery during 6 the 180 days prior to initial dialysis claim, (2) patients with cancer or blood disease during the 7 180 days prior to initial dialysis claim, and (3) patients who experienced an RBC transfusion- 8 related complication, by type of complication. We also performed sensitivity analyses by 9 excluding cost outliers (RBC transfusion episodes with the top 1% of blood acquisition and 10 administration costs or those with costs equal to $0 were excluded), varying the payment time 11 frames (using both a narrow and broad time window [defined in Figure 2] in identifying and 12 defining payment claims to RBC transfusion episodes), and estimating mean payment per unit of 13 blood based on a blood acquisition and administration claim analysis. 10 1 Results 2 Patient sample 3 From an initial sample of 105,260 patients with ≥ 2 chronic dialysis claims, we had a 4 final sample of 3,283 chronic dialysis patients who met all of the selection criteria. Requiring 6 5 months of pre-index data and ≥ 1 outpatient RBC transfusion contributed to the greatest loss of 6 subjects. Among the 3,283 chronic dialysis patients, there were 7,049 outpatient RBC 7 transfusion episodes used in the micro-costing analyses. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) patient 8 follow-up was 494.76 (474.19) days. 9 10 11 Patient demographics and clinical characteristics Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean (SD) 12 age was 60.9 (15.0) years, 56.4% of patients were men, and 40.9% of patients had Medicare 13 supplemental insurance. The three most frequent comorbidities were hypertension (93.9%), 14 diabetes (50.6%), and CHF (35.6%). Hemodialysis was performed in 60.8% of patients, 15 peritoneal dialysis in 6.3%, and type of dialysis was unknown in 33.4%. Patients experienced a 16 mean 2.15 transfusion episodes during the follow-up period. Transfusion was administered at 17 outpatient hospital facilities in 82.0%, ESRD facilities in 9.4%, hospital emergency rooms in 18 2.6%, and unknown in 6%. 19 20 21 Red blood cell transfusion episode payments The component and total payments for RBC blood transfusion episodes are presented in 22 Table 2. Mean (SD) total payment per RBC transfusion episode was $854 ($2,060). The median 23 payment was $427 (25th percentile, $53; 75th percentile, $1071), suggesting that payments were 11 1 not normally distributed. The largest component (72.0%) of the total payment was blood 2 acquisition and administration (mean, $615; SD, $1,237; median, $289). Pre- and post- 3 transfusion screening and monitoring component payments represented 22.6% of the total 4 payment (mean, $193; SD, $616; median, $34). Payments for complications when averaged 5 across all RBC transfusion episodes were relatively low (mean, $75; SD, $1,317; median, $0) but 6 individual episode payments ranged from mean (SD) $213 ($168) for delayed hemolytic 7 transfusion reaction to $19,466 ($15,424) for CHF. When evaluating total payments by primary 8 payer type, the mean payments were similar. Mean payments (median; SD) per RBC blood 9 transfusion episode were $855 ($388; $2,728) and $853 ($457; $1,428) for Medicare primary 10 and commercial primary, respectively. 11 Subgroup analyses 12 We estimated per RBC transfusion episode payments for 3 subgroups (Figure 3). 13 Screening and monitoring costs varied minimally between patients with cancer or blood disease; 14 patients with an acute bleed or surgery; and patients who did not have cancer, blood disease, 15 acute bleed, or surgery. However, there was significant variation in blood acquisition and 16 administration payments. Patients with cancer or blood disease had the highest mean payment 17 (mean, $737; SD, $1,502), followed by patients with neither acute bleed nor cancer (mean, $542; 18 SD, $1,044). Mean total payment per RBC transfusion episode was higher than base-case 19 estimates (Table 2) for patients with cancer or blood disease (mean, $969; SD, $1,948) and lower 20 than base-case estimates for patients with an acute bleed or surgery (mean, $733; SD, $1,195). 21 Figure 4 summarizes payments made for various types of transfusion-related 22 complications. Payments for CHF (mean, $19,466) and allergic reactions (mean, $11,655) were 23 the most expensive complication payments. TACO (63 episodes) and hyperkalemia (51 12 1 episodes), were the most commonly observed types of complications. Among the RBC 2 transfusion episodes associated with hyperkalemia complications, 69.1% of the hyperkalemia 3 events occurred on the same date as the RBC transfusion start date. 4 5 Sensitivity analyses 6 We performed sensitivity analyses by excluding cost outliers, varying time frames 7 (narrow- and broad-window time frames) and reestimating the component and total payments per 8 RBC transfusion episode. As shown in Table 3, relative to base-case estimates, screening and 9 monitoring component payments increased slightly when outliers were excluded (mean, $214; 10 SD, $451) and when we used the broad-window time frame (mean, $225; SD, $712) but 11 decreased slightly when we used the narrow-window time frame (mean, $172; SD, $598). Blood 12 acquisition and administration payments were higher when outliers were excluded (mean, $696; 13 SD, $701) but similar to the base case estimates when narrowing and broadening the time frame. 14 When using the broad-window timeframe, complication payments greatly increased from the 15 base case’s mean (SD) of $75 ($1,317) to a mean of $120 ($1,520). Total payment per RBC 16 transfusion episode was highest when cost outliers were excluded (mean, $971; SD, $1,982) and 17 when we used the broad-window time frame (mean, $931; SD, $2,239) compared to the base- 18 case estimates. 19 Finally, we estimated component payments per blood acquisition and administration unit. 20 Per-unit data were available for 340 outpatient RBC transfusion episodes. When these episodes 21 were analyzed, the transfusion screening/monitoring mean (SD) payment was $245 ($425), the 22 blood acquisition and administration mean payment was $433 ($495), and the mean payment for 23 transfusion complications was $153 ($1,915). Per-unit total transfusion episode mean payment 13 1 was $827 ($2,127). 14 1 Discussion 2 We evaluated 3,283 chronic dialysis patients with at least 1 outpatient setting RBC 3 transfusion episode. Most of the patients had diabetes measured during the pre-index period. In 4 the base case, 72.1% of the total payments were due to blood acquisition and administration, 5 with the remainder of payments attributable to screening and monitoring and, to a lesser extent, 6 transfusion-related complications. Total RBC transfusion payments were higher for patients 7 with cancer or blood disease than those with an acute bleed or in our base-case estimates. 8 Sensitivity analyses suggest that the base-case results were robust. Total payment estimates 9 increased when both the top 1% most expensive episodes and $0 payment episodes were 10 excluded. Payments became slightly lower when a narrow-window time frame was used and 11 increased slightly with a broad-window time frame. The variations in total payments among all 12 sensitivity analyses were less than 15% different from the base-case total payment estimates. 13 Across all sensitivity analyses, the blood acquisition and administration payments consistently 14 were the most expensive component payment. 15 Under the newly implemented Medicare PPS for ESRD patients, reimbursement is 16 capitated to include dialysis and previously separately billable medications and services. 17 Payments for blood and blood products are not, however, included in the new PPS bundle. As 18 patients are treated to a lower hemoglobin level, the resulting lower hemoglobin levels could also 19 create a medical necessity for RBC transfusions. The use of transfusions to supplement ESA 20 therapy in ESRD patients on dialysis may increase because of economic incentives and clinical 21 necessity. It is, therefore, important to comprehensively examine the transfusion-associated 22 payments made within the chronic dialysis patient population in order to understand the 23 economic consequences of the recent changes in reimbursement. 15 1 Our results differ somewhat from a recent cost analysis that used an activity-based 2 costing model of RBC transfusions in a surgical population (based on observation of real-life 3 activities in four hospitals in the United States and Europe) to identify the costs for each 4 transfusion-related task and resource [22]. Overall, total inpatient RBC transfusion costs were 5 $522 to $1183 (mean, $761) per unit across the four hospitals (a considerable portion of the costs 6 was related to pre-surgical testing for blood type/screening in patients who never received a 7 transfusion) [22]. These results were similar but slightly lower than our mean per-unit payment 8 estimate of $827 (SD, $2,127). Blood acquisition costs in the other study were only 21% to 32% 9 ($154 to $248 in 2008 dollars) of the total RBC transfusion-related costs. We found blood 10 acquisition and administration payments accounted for 50% to70% of total payments, but could 11 not differentiate acquisition and administration payments with certainty in the claims data. 12 Patient testing and administration and monitoring of RBC transfusions and pretransfusion 13 processes were 24% to 36% of total costs. Managing acute transfusion reactions and 14 hemovigilance contributed to 0% to 2% of costs [22]. The type and level of detail available in 15 the data as well as place of service (inpatient vs outpatient setting) may explain some of the 16 differences in our estimates from those of Shandler et al. Moreover, costs associated with blood 17 acquisition and administration can vary according to the amount (units) and type (eg, 18 leukoreduced or irradiated) of blood. 19 Our study had several limitations. We followed patients for mean 494.76 days, which 20 was not long enough to detect payments for iron overload. The analysis took a conservative 21 approach and excludes a number of potential resources that may increase the potential economic 22 burden. For example, a number of potential long-term complications, including infectious 23 diseases and iron overload, were excluded and may result in an underestimation of the overall 16 1 economic burden of RBC transfusions. In addition, long-term management of acute 2 complications such as medication costs and additional outpatient management were not included 3 in the analysis, all of which may result in underestimation of the overall economic burden of 4 RBC transfusions. Lastly, the economic burden may be underestimated because only 5 hospitalizations related to specific complications listed in Figure 2 were included. The analysis 6 may be potentially underestimating the economic burden by not including hospitalization that 7 may occur the day of or day after a RBC transfusion because this may be a result of the 8 transfusion exacerbating a existing condition or producing a new condition. Another limitation 9 is the potential to include acute renal failure patients in the analysis. Utilizing a large number of 10 dialysis claims over a long period may result in a much healthier population as a result of 11 inclusion criteria. To minimize the potential for including acute renal failure or only including a 12 healthier population of ESRD patients on dialysis, the analysis presented here utilizes specific 13 codes that are only utilized by ESRD patients on dialysis. Another includes hospitalizations 14 related to the specific acute complication events included in the micro-costing design. We did 15 not have information on patient race/ethnicity. We were missing type of dialysis in about one 16 third of cases. We did not evaluate inpatient costs because the inpatient claims data were based 17 on diagnosis-related group codes and could not be separated out into payment components, 18 therefore would have been obtaining what was probably an underestimation of the costs. Finally, 19 patients in our sample had either commercial insurance or Medicare plus Medicare supplemental 20 insurance as their primary coverage, and therefore, the results may not be generalizable to 21 patients who are uninsured, are covered only by Medicare, or have other types of insurance 22 coverage. 23 24 17 1 2 Conclusion 3 This is the first study to examine payments for outpatient RBC transfusions in a 4 population of patients undergoing chronic dialysis. Our study shows that payments for 5 outpatient RBC transfusion episodes are primarily driven by blood acquisition and 6 administration payments. Additionally, there are travel and other costs to dialysis patients for 7 RBC transfusion episodes and increased risk for allosensitization; these could not be estimated 8 here, but are important costs associated with RBC transfusions. While infrequent, transfusion 9 complications increase payments substantially when they occur. Better understanding of RBC 10 transfusion episodes’ payments and costs to patient may help inform policy makers when 11 determining the appropriate reimbursement policy for chronic dialysis patients. 12 18 1 2 Abbreviations 3 CHF, congestive heart failure; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; DOPPS, Dialysis 4 Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; ESRD, end-stage 5 renal disease; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; PPS, Prospective 6 Payment System; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation; TACO, transfusion-associated 7 circulatory overload; TRALI, transfusion-related acute lung injury; USRDS, United States Renal 8 Data System 9 10 19 1 2 Competing Interests 3 Dr. Spiegel has been a consultant, received research funding, and served on the speakers bureau 4 for Amgen, and has served on scientific advisory boards for Amgen and Genzyme. Dr. Carson 5 financial research support from Amgen. Dr. Custer received consulting fees from Amgen for 6 this project. Dr. Song, Dr. Cao, Dr. Cappell, and Ms. Varker are employees of Truven Health, 7 Cambridge, MA, which provides consulting services to clients, including the pharmaceutical 8 industry. Dr. Gitlin, Dr. Lee, Dr. Wan, and Dr. Ashfaq are employees and stockholders of 9 Amgen Inc. 10 11 20 1 2 Author Contributions 3 MG contributed to the conception of the study, study design, analysis and interpretation of the 4 data; contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript; and approved the final draft for 5 submission. JAL contributed to the conception of the study, study design, analysis and 6 interpretation of the data; contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript; and approved 7 the final draft for submission. DMS contributed to the conception of the study, study design, 8 analysis and interpretation of the data; contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript; 9 and approved the final draft for submission. JLC contributed to the conception of the study, 10 study design, analysis and interpretation of the data; contributed to the writing and revision of the 11 manuscript; and approved the final draft for submission. BSC contributed to the conception of 12 the study, study design, analysis and interpretation of the data; contributed to the writing and 13 revision of the manuscript; and approved the final draft for submission. SW contributed to the 14 conception of the study, study design, analysis and interpretation of the data; contributed to the 15 writing and revision of the manuscript; and approved the final draft for submission. AA 16 contributed to the conception of the study, study design, analysis and interpretation of the data; 17 contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript; and approved the final draft for 18 submission. XS contributed to acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of the data, 19 contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final draft for 20 submission. ZC contributed to acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of the data, 21 contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final draft for 22 submission. KAC contributed to acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of the data, 23 contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final draft for 21 1 submission. HVV contributed to the acquisition of the data, contributed to the writing and 2 revision of the manuscript, and approved the final draft for submission 3 22 1 2 Acknowledgments 3 We wish to thank Linda Rice, PhD, of Amgen Inc. and Julia R. Gage, PhD, of Gage Medical 4 Writing, LLC for their editorial assistance and Tracy Johnson, BA, of Complete Healthcare 5 Communications, Inc. on behalf of Amgen for post-submission editing assistance. This study 6 was funded by Amgen Inc. 7 23 1 References 2 1. 3 4 Sargent JA, Acchiardo SR: Iron requirements in hemodialysis. Blood Purif 2004, 22(1):112-123. 2. Churchill DN, Taylor DW, Cook RJ, LaPlante P, Barre P, Cartier P, Fay WP, Goldstein 5 MB, Jindal K, Mandin H et al: Canadian Hemodialysis Morbidity Study. Am J Kidney 6 Dis 1992, 19(3):214-234. 7 3. 8 Eschbach JW, Adamson JW: Anemia of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Kidney Int 1985, 28(1):1-5. 9 4. Data on File. Thousand Oaks, CA: Amgen Inc. 10 5. Beauregard P, Blajchman MA: Hemolytic and pseudo-hemolytic transfusion 11 reactions: an overview of the hemolytic transfusion reactions and the clinical 12 conditions that mimic them. Transfus Med Rev 1994, 8(3):184-199. 13 6. 14 15 Despotis GJ, Zhang L, Lublin DM: Transfusion risks and transfusion-related proinflammatory responses. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2007, 21(1):147-161. 7. Dodd RY, Notari EPt, Stramer SL: Current prevalence and incidence of infectious 16 disease markers and estimated window-period risk in the American Red Cross 17 blood donor population. Transfusion (Paris) 2002, 42(8):975-979. 18 8. 19 20 Pathol Lab Med 2007, 131(5):708-718. 9. 21 22 23 Eder AF, Chambers LA: Noninfectious complications of blood transfusion. Arch Gilliss BM, Looney MR, Gropper MA: Reducing noninfectious risks of blood transfusion. Anesthesiology 2011, 115(3):635-649. 10. Simon GE, Bove JR: The potassium load from blood transfusion. Postgrad Med 1971, 49(6):61-64. 24 1 11. Vella JP, O'Neill D, Atkins N, Donohoe JF, Walshe JJ: Sensitization to human 2 leukocyte antigen before and after the introduction of erythropoietin. Nephrol Dial 3 Transplant 1998, 13(8):2027-2032. 4 12. The 2009 National Blood Collection and Utilization Survey Report. Washington, DC: 5 US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for 6 Health; 2011. 7 13. Allain JP, Stramer SL, Carneiro-Proietti AB, Martins ML, Lopes da Silva SN, Ribeiro M, 8 Proietti FA, Reesink HW: Transfusion-transmitted infectious diseases. Biologicals 9 2009, 37(2):71-77. 10 14. 11 12 (NIS). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007-2009. 15. 13 14 Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP): HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample Kumar A: Perioperative management of anemia: limits of blood transfusion and alternatives to it. Cleve Clin J Med 2009, 76 Suppl 4:S112-118. 16. Goodnough LT, Strasburg D, Riddell Jt, Verbrugge D, Wish J: Has recombinant human 15 erythropoietin therapy minimized red-cell transfusions in hemodialysis patients? 16 Clin Nephrol 1994, 41(5):303-307. 17 17. Ibrahim HN, Ishani A, Foley RN, Guo H, Liu J, Collins AJ: Temporal trends in red 18 blood transfusion among US dialysis patients, 1992-2005. Am J Kidney Dis 2008, 19 52(6):1115-1121. 20 18. US Renal Data System: USRDS 1995 Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: The 21 National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney 22 Diseases; 1995. 25 1 19. Pisoni RL, Bragg-Gresham JL, Young EW, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Locatelli F, Bommer J, 2 Cruz JM, Kerr PG, Mendelssohn DC et al: Anemia management and outcomes from 3 12 countries in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am J 4 Kidney Dis 2004, 44(1):94-111. 5 20. 6 7 Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997. 21. 8 9 Drummond MF, O'Brien B, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW: Methods for the Economic- Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. 22. Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S, Theusinger OM, Gombotz H, Spahn DR: Activity- 10 based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 11 (Paris) 2010, 50(4):753-765. 12 13 14 26 1 Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics Patients N = 3,283a Age, mean years (SD) 60.9 (15.0) Sex, n male (%) 1,850 (56.4) Geographic region, n (%) Northeast 253 (7.7) North Central 975 (29.7) South 1,459 (44.) West 585 (17.8) Unknown 11 (0.3) Payer, n (%) Commercial 1,941 (59.1) Medicare 1,342 (40.9) Deyo Charlson comorbidity index, mean score (SD) 4.32 (2.45) Comorbid conditions, n (%) Hypertension 3,084 (93.9) Diabetes 1,662 (50.6) CHF 1,167 (35.6) Acute bleeding 748 (22.8) Surgery 719 (21.9) Cancer 680 (20.7) COPD 460 (14.0) Hyperkalemia 423 (12.9) Dialysis modality, n (%) 27 Patients N = 3,283a Hemodialysis Peritoneal dialysis Unknown Transfusion episodes with ≥ 30 days follow-up, mean 1,997 (60.8) 207 (6.3) 1,095 (33.4) 2.15 (3.78) number (SD) Length of follow-up, mean days (SD) 1 2 3 4 494.76 (474.19) Chronic dialysis patients with ≥ 1 outpatient red blood cell transfusion episode. CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD, standard deviation. a 28 1 Table 2. Base-case payment per red blood cell transfusion episode All Patientsa (N= 3,283); All Episodes (N = 7,049) Payments and Events Mean SD Median 25th 75th percentile percentile Min Max Transfusion screening/monitoring Blood acquisition and administration Transfusion complications $193 $616 $34 $0 $189 $0 $22,673 $615 $1,237 $289 $11 $801 $0 $30,962 $75 $1,317 $0 $0 $0 $0 $61,059 TOTAL screening, transfusion and complication payments Number of services per episode $854 $2,060 $427 $53 $1,065 $0 $74,452 2.87 2.93 2.00 0.09 5.00 0.00 20.00 Blood acquisition and 2.04 1.26 administration a 2 Patients with ≥ 1 outpatient red blood cell transfusion. 3 SD, standard deviation. 4 2.00 1.00 3.00 1.00 12.83 Average payment per episode All payers Transfusion screening/monitoring 29 1 Table 3. Sensitivity analysis of RBC transfusion episode payments by time frame Drop Top 1% and Bottom Narrow Broad Base Case $0 Patients Window Window Mean payments (SD) (N = 7,049) (N = 4,844) (N = 7,049) (N = 7,049) Screening/monitoring $193 (615) $214 (451) $172 (598) $225 (712) Acquisition/administration $615 (1,237) $696 (701) $615 (1,237) $615 (1,237) Complication $75 (1,317) $86 (1,541) $56 (1,149) $120 (1,521) $854 (2,060) $971 (1,982) $814 (1,940) $931 (2,239) Total payment per RBC transfusion 2 3 RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation. 30 1 Figure Legends 2 Figure 1. Patient selection time frame. 3 Figure 2. Transfusion episode time frame. Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; 4 TACO, transfusion-associated circulatory overload; TRALI, transfusion-related acute lung 5 injury. 6 Figure 3. Red blood cell transfusion episode payments for patients with history of acute 7 bleed/surgery or cancer/blood diseases. 8 Figure 4. Mean red blood cell transfusion payments for patients with complications, by 9 type of complication. Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; TACO, transfusion- 10 associated circulatory overload. 11 31 1 2 Figure 1 3 4 5 6 32 1 2 Figure 2 3 4 5 6 33 1 2 Figure 3 3 4 5 34 1 2 Figure 4 3 4 5 35 1 Supplementary Material: Inpatient and Outpatient Transfusion Billing Codes 2 Table S1. Codes for chronic dialysis claims Code Type Code Description UB-02 (Rev Code) 821 Hemodialysis/composite or other rate UB-02 (Rev Code) 831 Peritoneal/composite or other rate UB-02 (Rev Code) 841 CAPD/composite or other rate UB-02 (Rev Code) 851 CCPD/composite or other rate CPT 90918 corresponds to HCPCS G0308-G0310, G0320 CPT 90919 corresponds to HCPCS G0311-G0313, G0321 CPT 90920 corresponds to HCPCS G0314-G0316, G0322 CPT 90921 corresponds to HCPCS G0317-G0319, G0323 CPT 90922 corresponds to HCPCS G0324 CPT 90923 corresponds to HCPCS G0325 CPT 90924 corresponds to HCPCS G0326 CPT 90925 corresponds to HCPCS G0327 HCPCS G0308 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients under 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0309 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment for patients under 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2 or 3 face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0310 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients under 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month HCPCS G0311 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients between 2 and 11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0312 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients between 2 and 11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2 or 3 face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0313 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients between 2 and 11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month HCPCS G0314 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services, during the course of treatment, for patients between 12 and 19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0315 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients between 12 and 19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2 or 3 face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0316 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients between 12 and 19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of 36 Code Type Code Description growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month HCPCS G0317 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients 20 years of age and over; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0318 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients 20 years of age and over; with 2 or 3 face-to-face physician visits per month HCPCS G0319 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services during the course of treatment, for patients 20 years of age and over; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month HCPCS G0320 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis patients per full month; for patients under two years of age to include monitoring for adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents HCPCS G0321 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis patients per full month; for patients two to eleven years of age to include monitoring for adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents HCPCS G0322 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis patients per full month; for patients twelve to nineteen years of age to include monitoring for adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents HCPCS G0323 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis patients per full month; for patients twenty years of age and older HCPCS G0324 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services less than full month, per day; for patients under two years of age HCPCS G0325 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services less than full month, per day; for patients between two and eleven years of age HCPCS G0326 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services less than full month, per day; for patients between twelve and nineteen years of age HCPCS G0327 End stage renal disease (ESRD) related services less than full month, per day; for patients twenty years of age and over CPT 90951 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients younger than 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90952 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients younger than 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2-3 face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90953 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients younger than 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month CPT 90954 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 2-11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90955 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 2-11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2-3 face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90956 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 2-11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month CPT 90957 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 12-19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month 37 Code Type Code Description CPT 90958 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 12-19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 2-3 face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90959 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 12-19 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month CPT 90960 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 20 years of age and older; with 4 or more face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90961 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 20 years of age and older; with 2-3 face-to-face physician visits per month CPT 90962 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services monthly, for patients 20 years of age and older; with 1 face-to-face physician visit per month CPT 90963 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis per full month, for patients younger than 2 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents CPT 90964 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis per full month, for patients 2-11 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents CPT 90965 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis per full month, for patients 1219 years of age to include monitoring for the adequacy of nutrition, assessment of growth and development, and counseling of parents CPT 90966 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for home dialysis per full month, for patients 20 years of age and older CPT 90967 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for dialysis less than a full month of service, per day; for patients younger than 2 years of age CPT 90968 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for dialysis less than a full month of service, per day; for patients 2-11 years of age CPT 90969 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for dialysis less than a full month of service, per day; for patients 12-19 years of age CPT 90970 End-stage renal disease (ESRD) related services for dialysis less than a full month of service, per day; for patients 20 years of age and older 1 38 1 2 3 4 Table S2. Billing codes for transfusions administered in the outpatient setting Code Type Code Description UB-04 0390 General Classification: Blood Processing and Services UB-04 0391 Blood Administration UB-04 0392 Blood Processing and Storage UB-04 0399 Other Blood Handling UB-04 0380 General Classification: Blood Products UB-04 0381 Packed Red Cells CPT 36430 Transfusion, blood or blood components CPT P9011 Blood (split unit), specify amount CPT P9016 Red blood cells, leukocytes reduced, each unit CPT P9021 Red blood cells, each unit CPT P9022 Red blood cells, washed, each unit CPT P9038 Red blood cells , irradiated, each unit CPT P9039 Red blood cells, deglycerolized, each unit CPT P9040 Red blood cells, leukocytes reduced, irradiated, each unit CPT P9051 Whole blood or red blood cells, leukocytes reduced CPT P9054 Whole blood or red blood cells, leukocytes reduced, frozen, deglycerol, washed, each unit CPT P9057 Red blood cells, frozen/deglycerolized/washed, leukocytes reduced, irradiated, each unit CPT P9058 Red blood cells, leukocytes reduced, CMV-negative, irradiated, each unit Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; CPT, current procedural terminology. 39 1 2 3 4 Table S3: Diagnosis codes for transfusion-related complications in the outpatient setting Code Type Code Category Description ICD-9-CM Dx 398.91 CHF Rheumatic (congestive) heart failure ICD-9-CM Dx 402.x1 CHF Hypertensive heart disease with heart failure ICD-9-CM Dx 404.x1 CHF Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified ICD-9-CM Dx 404.x3 CHF Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease with heart failure and chronic kidney disease stage V or end stage renal disease ICD-9-CM Dx 428.xx CHF Heart failure ICD-9-CM Dx 708.0 Allergic reaction Allergic urticaria ICD-9-CM Dx 995.0 Allergic reaction Other anaphylactic shock ICD-9-CM Dx 999.4 Allergic reaction Anaphylactic shock due to serum ICD-9-CM Dx 999.83 Hemolytic transfusion reaction Hemolytic transfusion reaction, incompatibility unspecified ICD-9-CM Dx 999.84 Hemolytic transfusion reaction Acute hemolytic transfusion reaction, incompatibility unspecified ICD-9-CM Dx 999.85 Hemolytic transfusion reaction Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, incompatibility unspecified ICD-9-CM Dx 999.6x Hemolytic transfusion reaction Hemolytic transfusion reactions ICD-9-CM Dx 999.7x Hemolytic transfusion reaction Hemolytic transfusion reactions ICD-9-CM Dx 276.7 Hyperkalemia Hyperkalemia ICD-9-CM Dx 999.1 Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis Other, including febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis following transfusion ICD-9-CM Dx 999.2 Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis Other, including febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis following transfusion ICD-9-CM Dx 999.80 Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis Transfusion reaction, unspecified ICD-9-CM Dx 999.89 Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis Other, including febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis following transfusion ICD-9-CM Dx E934.7 Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis Other, including febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, air embolism or phlebitis following transfusion ICD-9-CM Dx 276.6x TACO Fluid overload disorder ICD-9-CM Dx 518.7 TRALI Transfusion-associated acute lung injury (TRALI) Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; TACO, transfusion-associated circulatory overload; TRALI, transfusion-related acute lung injury. 5 40