Analyzing European media policy: Stakeholders and advocacy

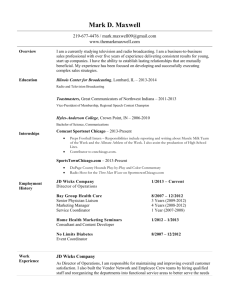

advertisement

Analyzing European media policy: Stakeholders and advocacy coalitions Hilde Van den Bulck and Karen Donders Media Policy: From Outcome Analysis to Process Analysis Media policy analysis seeks to “examine the ways in which policies in the field of communication are generated and implemented, as well as their repercussions or implications for the field of communication as a whole” (Hansen et al., 1998, p. 67). Most critical academic media policy research is conducted ex post, tracing how certain policy outcomes came about, why certain policy outcomes rather than others became dominant, what parties were involved in the decision making process, and how power was distributed amongst them (Freedman, 2008; Fischer, 2003). As such, a rich tradition of research into media policy has developed, including analysis of media policies at the level of the European Union (EU). Indeed, ever since the EU (at the time the European Community) – and especially the European Commission (EC) – started taking an interest in media in the 1980s, an extensive literature developed on the specifics of EU media policy and the impact on the media landscape in its Member States (see the introduction in this book). Scholars working in this area show an in-depth understanding of particular policy outcomes and a detailed knowledge of the legal and factual events leading up to them, but they do not often provide a systematic analysis of the actual process of EU media policy making as such. What is more, while scholars contextualize policy decisions and the implications hereof in conceptual-theoretical models about the relationship between media, society and the state, less attention is paid to (the application of) models and tools in other academic disciplines such as political sciences that can help explain EU decision making in the area of media. This is where this chapter wants to contribute by providing an analytical framework that can be used as a tool to analyze and better understand this complex process of EU media policy making. To this end, the chapter first discusses stakeholder analysis – often implicitly applied in media policy research – as a preliminary inroad into identifying relevant actors, their arguments and logic, their visibility and prominence in the policy process. Yet such a focus on actors cannot fully explain the entire process through which policies come about. Therefore this chapter introduces Sabatier’s (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993) Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) and analyses how (and to what extent) this model can provide a framework to deal with the specifics of EU media policy making structures and mechanisms. In doing so, we will evaluate the usefulness of the model to understand the allocation of power in the policy process. Throughout, conceptual issues are illustrated with recent EU media policy developments in the area of public service broadcasting. The chapter will not provide new insight into the actual EU policy with regard to public service broadcasting (see chapter by Donders & Moe). A rich and detailed literature in this area already exists. Instead, it will provide conceptual tools for a better understanding of the complex and multi-layered EU media policy process that lies behind these policy outcomes. Stakeholders in the EU Policy Arena Stakeholder analysis: itinerary, concepts and tools Although rarely identified as such, much of the work dealing with EU media policy is in fact a form of stakeholder analysis, a policy analysis model with a considerable tradition in other fields of enquiry, including business management (e.g. Mitchell et al., 1997), health care (e.g. Brugha & Varvasovsky, 2000), and development and environmental studies (e.g. Prell et al., 2009). Even though “each [policy] sector poses its own problems, sets its own constraints, and generates its own brand of conflicts” (Freeman, 1985, p. 469), and although institutions and loci of power to influence policy outcomes differ across sectors (Howlett, 2004), these studies provide conceptual tools applicable to and useful in the field of EU media policy. Stakeholder analysis considers a “policy decision the result of a process characterised by formulation of views and interests, expressed by actors or stakeholders that adhere to a certain logic and that engage in debate and work towards a policy decision on relevant forums” (Van den Bulck, 2012, p. 219). Understanding the media policy process by means of stakeholder analysis involves a number of analytical steps (see Van den Bulck, 2012). It starts from a broad understanding of the main structures and processes of and policy venues involved in decision-making, in this case in the EU. It next requires the identification of all relevant stakeholders: i.e. individuals, groups, organizations and institutions with a vested interest in a particular policy issue or its outcome. In the field of media policy these can include: - national (government, parliament, regional entities, etc.) and transnational (European Commission, distinct Directorate Generals, European Parliament, Council of Ministers, etc.) governmental bodies; - politicians (e.g. former Belgian prime minister Dehaene and former German chancellor Kohl pushing for the adoption of the Amsterdam Protocol in 1997, cf. supra); - regulatory institutions (European courts, media regulators and National Competition Authorities); - media interest groups (like the Association of Commercial Television, the European Broadcasting Union, and the European Publishers Council); - media companies (including multinationals and smaller undertakings); and - citizens and other representatives of civil society. Identifying stakeholders is usually a dynamic, iterative process, as unexpected parties may surface while analyzing and collecting data on developing European media policies (e.g. civil society groups claiming an increasingly important role in policy initiatives on piracy), as well as during data collection and analysis. Interestingly, the category of stakeholders does not entirely overlap with that of policy actors. Certain stakeholders with a distinct interest in a certain outcome may not actually take part in the policy process (with large sections of media audiences as a typical example), while policy actors with no explicit stake such as academics and civil servants can considerably influence the outcome of the process. Once identified, stakeholders can be characterized on the basis of their attitude towards the policy issue at hand, and of the main logic they adhere to. The latter relates to the perception of the situation and the structure of goals and means in a certain situation (Van den Bulck, 2008). Within the field of (European) media policy, arguments are formulated mainly within a technological, economic, political, and/or cultural logic. Two stakeholders can be in favour of a certain policy outcome but can argue this on the basis of a different logic, while a shared logic not necessarily results in the same policy preference. For example, two companies proposing a merger in the area of pay-television will argue for approval by the European Commission (in case of a European interest) or National Competition Authority on the basis of their own, profit-seeking interests. A Member State might lobby in favour of approval seeking to further the emergence of a ‘national champion,’ being able to fight competition from other Member States or even countries external to the EU. In the alternative, two Member States can share their support for domestic children’s programming with one Member State introducing a prohibition of advertising before and after children’s programming, while the other one suppresses such a prohibition as it wants to avoid undermining the competitiveness of its own domestic providers of children’s content. The approach to combine actor positions with gaining an insight in underlying logics fits with a recent trend in media policy studies advocating for a focus on the role of ideas. Incorporating such an ‘ideational’ view can overcome a too strong focus on realpolitik and what stakeholders want by also looking at “their worldviews, values and cognitive frames or intellectual paradigms—which may themselves shape actors” interests’ (Parker & Parenta, 2008, p. 4). It further allows to take into account nonrational, rather symbolic, motives, that are often present in EU media policy debates. Stakeholders in EU public service broadcasting policy making Decision making at the EU level is a complex affair. In the most general sense, its key policy actors are the national governments of the – currently 27 – Member States and the EU supranational political institutions, the European Parliament and the European Commission. In decisions of “history making proportions” (Warleigh-Lack & Drachenberg, 2012, p. 221) Member State governments have all meaningful power, negotiating e.g. in the Council of Ministers. In other policy making, including with regard to public service broadcasting, the key supranational actor is the European Commission whose main stake is to make sure Member States comply with the single market and State aid rules. The latter particularly holds for the position of public broadcasters in national media markets, making not just the European Commission’s Directorate General Communication Networks, Content and Technology (DG Connect, formerly Information Society and Media) and the DG for Education and Culture, but even more so DG Competition key actors in public service broadcasting policy making (Donders & Pauwels, 2010). The European Court of Justice, finally, cannot initiate policy but can nevertheless as a court of appeal be considered a policy maker (Harcourt, 2005). In fact, the General Court (ex Court of First Instance) has been a very important actor in driving European Commission action in the field of public service broadcasting. Answering to private sector complaints on the lack of action of the European Commission in the area of State aid to public broadcasters, the General Court ruled in three consecutive occasions that the European Commission failed to act. Hence, it instigated European Commission action in this domain (see Donders, 2012). Four – related – characteristics of the EU media policy making system strongly impact on the number of policy actors that come into play. The first is its multi-level governance transnational nature together with its large scale and complexity all of which result in a wide range of possible actors involved. This is enhanced, second, by the institutionalized position of interest groups in EU policy making. They are crucial in providing the necessary expertise in terms of information and ideas, and thus “support the output legitimacy of EU public policy” (Carboni, 2006; p. 6). As a result, the European Commission allows and encourages – e.g. through consultation rounds – a great many policy actors and stakeholders to be part of media policy making, including in the field of public service broadcasting, film support, etc. Thirdly, the symbolic nature of certain EU media policy issues can add to the number of, in particular, political stakeholders that want to participate in discussions. Public service broadcasting, for example, has a highly symbolic position within Europe, provoking many politicians to ask parliamentary questions in their home parliaments, in the European Parliament, or send letters to the European Commissioner for Competition. Fourthly, the multi-faceted (i.e. cultural and economic) nature of media makes EU media policy a domain that is claimed by many stakeholders. Public service broadcasting policy making at the European level has thus become a multi-stakeholder affair with, next to the EU institutions, a wide range of actors and stakeholders involved in the process (both invited and unsolicited), including public and private broadcasters, radio operators, film producers and distributors, newspaper publishers, advertisers, cable and satellite operations, telecom companies and their respective sectoral organizations, trade unions, religious groups and many other civil society organizations and individuals, cultural and other research institutes and academic and other experts (Commission Staff working paper, s.n.; Van den Bulck, 2008; Donders & Pauwels, 2010). Some of the most active stakeholders that scholars (cf. Bardoel, 2009; Donders & Pauwels, 2008; Pauwels & De Vinck, 2007; Soltész, 2010) have identified in EU public broadcasting policy making in the past decade, are public broadcasters’ main competitors, commercial broadcasters and newspaper publishers. While many European states have enabled public broadcasters a strong market position and, for reasons of technological nationalism, have given them a leading role in digitization and the development of new media technologies (Smith & Steemers, 2007; Van den Bulck, 2007), commercial stakeholders have protested the wide scope of activities, the position of public broadcasters vis à vis technological developments and new media services, and the market distortion effect of public broadcasters funding, adhering mainly to an economic logic. In the past decade many complaints launched by these key stakeholders were filed with the European Commission, indicating their visibility and significance. As the extensive literature on this topic indicates, these stakeholders’ attempts seem to have contributed successfully to the recent changes in the European Commission’s public service broadcasting policy resulting in the stipulations in the renewed 2009 Broadcast Communication outlined above, with tighter definitions of the public broadcasting remit in many national legislations and the introduction of ex ante tests for significantly new services as the main outcomes (Ridinger, 2009; Soltész, 2010; Tosics et al., 2008; Donders & Moe, 2011). Conceptual Blind Spots in Stakeholder Analysis Although stakeholder analysis is essential to understand how particular media policies take shape, it has a number of shortcomings, resulting in blind spots in policy process mapping. First, it tends to be inspired by an ‘institutional’ view of the media policy process, focusing on formal and visible points of decision-making (e.g. the European Commission) and on institutional arrangements (Parker & Parenta, 2008). This may result in a failure to identify key non-institutional and informal policy-making venues, where stakeholders work outside of ‘official’ policy channels (Freedman, 2008; Kingdon, 1995; Lindquist, 2001, p. 13). This may lead, second, to an inability to detect all relevant actors and stakeholders that were instrumental in a particular policy outcome. This may include less visible but potentially influential stakeholders or civil servants and other actors that may not have a direct stake in but nevertheless exert a considerable influence on the policy making process (Van den Bulck, 2008). There is a need for a more complex view of all those involved in the policy process, their positions and interrelations. Third, as most stakeholder analyses focus on a specific case or issue, they quickly become ‘outdated’ as actors and their arguments and logics are likely to shift from one case to the next. This, according to Weible (2007), makes it difficult to get a long term, systematic stakeholder map. There is also a need for “a wider scope, recognizing that stakeholders typically are not concerned with just one policy venue or alternative but with the outcomes of an entire policy subsystem over long periods of time” (Weible, 2007, p. 97). Fourth, there is a need for a better conceptual understanding of the dynamics of the policy process as a means to identify who gets something on the policy agenda, how different stakeholders relate to one another and to key policymakers, and how the decision-making process works formally and informally. Identification of stakeholders and policy actors in itself cannot account for their individual or combined visibility, impact and power nor for the policy processes in which they take part. As argued by Donders and Raats (2012, pp. 14-15) media policy making – like in other areas – remains something of a black box. Their conclusion is based on a discussion of Flemish and Dutch public service broadcasting policy decisions but since EU media policy adds levels of policy making and numbers of actors, the issue is all the more relevant and provides an additional argument to look for a more solid basis for policy process analysis. The Policy Process: The Advocacy Coalition Framework From Actors to Process To overcome these blind spots and fully grasp the complexity of policy making, it is necessary to extend the focus on policy actors with a model that focuses on the policy process: how do the policy decisions come about? John (2003) contends that, regardless of a pluralist consensus, a critical conflict, or a mixed position, the policy process must be considered as complex, involving not just a wide variety of actors and institutions but also a complex web of relations between them and a multitude of sources of causation and feedback. One potentially useful model is Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith’s (1993; 1999) Advocacy Coalition Framework. The model considers the policy process as “a competition between coalitions who advocate beliefs about policy, problems and solutions” (Carboni, 2009). While developed in the 1990s within the context of the US political system, Sabatier (1998a) himself indicated that his model in the context of the EU can function as “at least a useful ordering framework for identifying important variables and relationships” (Sabatier, 1998a, p. 120). By the mid 2000s Sabatier and Weibles (2007) showed that one out of three ACF studies deals with Europe, half of which with the EU (e.g. Dudley & Richardson, 1999; Radaelli, 1999). More recently, the model has been applied to EU policy making areas including energy (Engel, 2007), health (Carboni, 2009) and immigration (Carammia, 2009), to name but a few. This, combined with the characteristics of EU policy making identified above, heightens the likely applicability of EU policy in the field of EU media policy. Policy Subsystems, Advocacy Coalitions and Belief Systems The ACF assumes that there are sets of core ideas about causation and value in public policy with regards to key policy issues around which subsystems develop. A subsystem groups a range of actors and stakeholders involved in a policy issue and exists when a set of actors, that consider themselves a policy community and that have expertise in a specific area for which there exist specific government agencies, seek to exert their influence on policy making in this area (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1993, p. 124). While the notion of a subsystem resembles conceptualisations such as Pross’ (1986) policy communities or Haas’ (1992) epistemic communities, Sabatier’s original contribution lies in what he identifies as advocacy coalitions, a notion that links the structural (policy processes and structures) and the individual (beliefs). He considers advocacy coalitions as a range of actors and stakeholders that “both (1) share a set of normative and causal beliefs and (2) engage in a nontrivial degree of coordinated activity over time” (Sabatier & Jenkins-Smith, 1999, p. 120). These coalitions and the relationships between the ‘members’ can be tight or loose and cut across governmental and non-governmental boundaries as well as across central and peripheral policy actors. What links actors into a coalition is a shared belief system: a set of beliefs and a general agreement on the best solution to a certain policy issue. This belief system is the glue that holds an advocacy coalition together and, according to Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith (1993), is hierarchically structured into three levels. The deep core relates to normative views on the individual, society, its institutions and the state and how they relate to one another. Here reference can be made to the divide between liberal and dirigiste approaches (see Collins, 1994) to EU media policy; the first normative view adhering to free market principles, whereas the second sets out from the need of government intervention to ensure a free flow of ideas and a genuinely diverse media landscape. The second level or policy core refers to causal perceptions such as the adequate level of government involvement or magnitude of the policy problem, and the subsequent policy positions. For example, liberals will accept a certain level of under-provision of socially desirable services and argue for a distributed public service delivery, whereas dirigistes (even if accepting market failure rationales on media) would still favour a specific institution to be in charge of public service delivery. The final level consists of secondary aspects and consists of more narrow and empirically based beliefs on how to implement the policy core and includes preferences for certain regulatory instruments over others (e.g. a preference for competition law over sector-specific ownership concentration rules to remedy issues related to external pluralism). According to Sabatier (1998a), typically two to four advocacy coalitions can be found in every policy community with regard to a particular issue, and it is possible to identify these networks of actors within a policy sector. Radaelli (1999, p. 664) explains how a certain (new) policy issue will first witness a state of fluidity, after which the policy process starts to structure. Actors and stakeholders start to assemble into coalitions, a process often helped by a so-called focusing event (e.g. a complaint or law suit) that lays bare underlying conflicts and clashes of beliefs. Advocacy coalitions will work to influence decision makers to act in accordance with their policy core by “using venues provided by the institutional structure through which they can exert influence in an efficient way” (Carboni, 2009, p. 6). Sabatier maintains that different advocacy coalitions can been seen to fight it out until one coalition emerges as the dominant one, controlling the key instruments of policy-making and implementation. As the policy issue matures, still according to Sabatier (1998a), advocacy coalitions become stable. In EU media policy there are a number of ‘usual suspect’ coalitions, being divided along economic versus cultural, national versus European (revolving around subsidiarity issues), and liberal versus dirigiste approaches. ACF and EU public service broadcasting policy Re-analyzing the existing literature and documents on EU public service broadcasting policy making from a ACF perspective, it is safe to say that the issue constitutes a subsystem that started to developed in the early 1990s and received its formal institutionalization in the Amsterdam Protocol (1998), that has the European Commission as main EU ‘government agency,’ and that gathers a large group of stakeholders (cf. supra) that make up a policy community, working to exert their influence. We can broadly identify two main advocacy coalitions that may disagree internally on certain secondary aspects but are united and interact around core beliefs (see Donders, 2012). One advocacy coalition can be described, maybe somewhat simplistically, as public service broadcasting believers. The roots of its belief system is the social responsibility view on the relationship between state, media and society, the belief in the ‘visible hand’ of government that has a duty to certain universal access for all to key services, including media, that are too important to be left to the market (Siebert et al., 1956; Humphreys, 1996; Moe, 2011). From this deep core follows the notion of responsibility of public policy to guarantee the continuation of a publicly-funded and flourishing public broadcaster that is legitimized by its core principles: “universality and diversity of provision, democratic accountability to the public as a whole, responsibility for meeting general and specific needs as decided by the public, a commitment to quality, not determined by profit or the market” (McQuail, 2003, p. 35; see also, Van den Bulck, 2001; Garnham, 1990). Regarding the extent to wich public service broadcasting should venture into the world of digitization and new media, this coalition adheres to what Jakubowicz (2007) calls an “everything is legitimate” position, proposing a move to public service media to even better ensure access for all citizens. While some believe public service broadcasting should be allowed to be part of the digital developments, others are even convinced that public broadcasters should proactively work to develop new possibilities as it will allow them to even better fulfill their remit (Bardoel & Lowe, 2007). This is translated into secondary aspects of the belief system such as the need for public or public/commercial funding or the recognition of the role in digitization in public service remits (e.g. ‘Building Digital Britain’ as one of the goals in the BBC Royal Charter (Barnett, 2006, p. 19)). Stakeholders that are part of this coalition include many of the EU Member States (but not all as some Member States oppose European Commission intervention not so much because they are believers, but more so because they oppose European intervention in what they consider a domain of national competences), public broadcasters and their sectoral representative the EBU, as well as cultural organizations, the educational field, academics, the Council of Europe, etc. The other advocacy coalition can be identified as public service broadcasting skeptics. The deep core of this coalition is based on a liberal view on the relationship between state, media and society, in favour of free market principles and the invisible hand of the state which argues against state intervention (e.g. through government funding) except in cases of market failure (Siebert et al. 1956; Bennett, 2006). As a basis for any media system, this is translated in a view on public service broadcasting from a market failure perspective that publicly funded broadcasting should be limited to what the market does not provide. Views on the latter can vary according to Jacubowicz (2007) from an attrition model (the market is increasingly making public broadcasting unnecessary) to an obsolete model that believes that the market provides for all and public broadcasting is therefore no longer needed. These models return in the view on digitization and new media which are believed to open up an array of new business opportunities, give way to an abundance of services, and considerably lower market entry (Armstrong & Weeds, 2007). ‘Interference’ of public broadcasters is thus unnecessary (the market is not failing) and would only distort the market. In other words, new services readily available on the market should not be delivered through state intervention. Interpreting the development of the EU public service broadcasting media policy within Sabatier’s framework, it can be seen as an ongoing ‘battle’ between these coalitions. While the Amsterdam Protocol may be seen as a ‘victory’ of believers over skeptics, the protocol left much room for policy negotiations for skeptics, resulting in the ongoing struggle between the two coalitions. In that regard, our case seems to contradict Sabatier’s suggestion that, once faught out, policy coalitions and their position and power in the policy process become stable. Given the above-mentioned policy making structures of the EU, it is not surprising that the main policy venue for public broadcasting issues is the European Commission, although the European Parliament (and recognized to a lesser extent, the Council of Ministers) proved an important venue in the establishment of the Amsterdam Protocol (Bardoel, 2009), possibly because of the strong advocacy work of the believers’ advocacy coalition. Accounting for policy change In general, a policy community maintains the status quo as it is built around deep core beliefs. How then to account for policy change, i.e. more or less radical shifts in policies. The ACF sees policy change as “a transformation of a hegemonic belief system within a policy subsystem” (Carboni, 2009, p. 6) and provides a complex view on how such change can come about. First, changes in policy making are influenced by dynamic exogenous factors such as changes in socio-economic circumstances (e.g. the move away from the welfare state), in governmental structures (e.g. growing relevance of subsidiarity system) and policy decisions in other subsystems and policy areas (e.g. liberalization of the telecommunications market). For instance, the neoliberal questioning of the welfare state and its institutions can be seen to strenghten claims of the liberal advocacy coalition. Change can further be seen to appear through policy-oriented learning or through shocks in the system. Policy-oriented learning refers to the evaluation and lessons learned from one policy implementation that affect a subsequent policy decision. Such policy-oriented learning can appear within but also between coalitions. The latter case often requires interference from so-called policy brokers, that “mediate the conflicting belief systems, looking for some reasonable compromise which will reduce conflict intensity” (Carboni, 1999, p. 6). According to Sabatier, policy-oriented learning (and subsequent change) is most likely and easily to take place at the level of secondary aspects of the belief systems. Changes in the core beliefs and thus major policy changes can only take place as the result of a shock to the system that originates externally or internally, as acknowledged in more recent adjustments to the advocacy coalition model (Weible et al., 2009). These shocks can cause actors to shift advocacy coalitions. It may also cause coalitions to adapt their arguments to new situations and even move across coalition divides. The balance of power in changes and the structure and memberships of coalitions alter (John, 2003). Explaining Change in EU public service broadcasting policy Overlooking the movements in EU public broadcasting policy making it appears that the changes have mainly occurred at the ‘lower’ level of the belief system, the secondary beliefs relating to legal frameworks (better or re-articulation of the public service remit in national legislation) and operational criteria and policy tools (ex ante tests). While not without considerable effect for the remit, functioning and position of public broadcasters, it has not hit the core and policy beliefs of both coalitions. It is further interesting to see that policy changes mainly resulted from policy-oriented learning both within and between coalitions. This is where the framework proves its usefulness as a tool to better understand the EU public broadcasting policy making, as stakeholder analyses often underestimate this learning process, particularly between coalitions, in favour of a view that a policy decision is attributed to one winner. EU public broadcasting policy making is an interesting example of how coalitions learn from one another. Indeed, the ex ante test developed by the BBC – an institution clearly related to the advocacy coalition of public service broadcasting believers – in response to complaints from skeptics was subsequently ‘adopted’ as a preferred policy outcome by a range of stakeholders from the public service broadcasting skeptical advocacy coalition to further their battle (Collins, 2011). On the other hand, experiences and advocacy work from believers resulted in an adjustment of the ex ante test for ‘any’ new public broadcast service to be modified in the 2009 Broadcasting Communication to ‘significant’ new services (Bardoel, 2009; Van den Bulck & Moe, 2012). The policy-oriented learning between advocacy coalitions is also interesting to better grasp the role of the European Commission (which is not a unified stakeholder either!) as a policy broker. For instance, in the period between the 2001 and the 2009 Broadcasting Communication was seen to “mediate between conflicting interest during political negotiations, control information, and translate divergent opinions into compromises” (Carboni, 2009, p. 29), In case of complaints of commercial competitors, it was the EC who negotiated with the Member States to adjust its legislation, and in the run up to the 2009 Broadcast Communication it organized a public hearing to allow stakeholders to influence the revision of the document. Discussion and Conclusion As far as EU media policy is concerned, “the question whether the ACF as proposed by Sabatier and his associates furnishes an analytical device that can effectively be deployed and trusted to identify the salient explanatory aspects of policymaking” (Füg, 2009, p. 2) can be answered in the affirmative, be it with a range of critical comments. First, analysis of EU public service broadcasting policy making seems to contradict Sabatier’s notion of coalitions fight it out until one becomes dominant after which a time of stability sets in. Our case in fact confirms Carboni (2009 see also Wallace, et al., 2010) observation that the characteristiscs of the EU policy making arena result in a system based not on a majoritarian ‘winner takes all’ logic but on consensus. However, this does not in itself undermine the central notion of the role of advocacy coalitions, nor does it suggest a level playing field in terms of power of different stakeholders. Competition and power struggles between advocacy coalitions exist but, rather than a clear win-lose as Sabatier suggest, they operate within “a delicate balance of power between and within multiple levels, institutions and actors, carefully crafted to ensure that none of its principal stakeholders are left with only losses and no gains” (Carboni, 2009, p. 6). Second, several instances of public service broadcasting policy making seem to suggest that stakeholders form or become part of an advocacy coalition for utilitarian reasons rather than on the basis of deep core beliefs. This is confirmed in applications of the ACF model to EU policy making in other sectors, such as Quaglia’s (2008) analysis of EU policies relating to securities trading in the financial sector. As an example in the area of public service broadcasting we can refer to newspaper groups filing complaints against public service broadcasting’s new media ventures for fear of their own viability rather than for certain deeply held beliefs with regards to the legitimacy of public service broadcasting institutions as such. Sabatier (1998a) recognises this and explains that while the framework assumes that actors are instrumentally rational and that there are always a level of free-riders in policy making, it “does not assume that actors are driven primarily by simple goals of economic/political self-interest, nor does it assume that self-interested preferences are easy to ascertain” (Sabatier, 1998a, p. 109). The system assumes that ‘policy core beliefs – because they are fairly general in scope yet very salient – provide more efficient guides to behaviour over a wide variety of situations than do secondary aspects’ (Sabatier, 1998, p. 109). Third, grouping the myriad of stakeholders, views and positions into a limited number of advocacy coalitions holds a danger of (over)simplification, of overly reducing complexity. In the case of public service broadcasting where we identified two (opposing) coalitions, one might wonder about those holding the more extreme view of public service broadcasting as being obsolete or about those holding in-between positions? Are there not three or more advocacy coalitions? In response, it is important to underline, first, that an advocacy coalition is not just about beliefs but also about engaging “in a nontrivial degree of coordinated activity over time” (cf. supra). Second, coalitions can be seen to gather around core beliefs but within a coalition stakeholders may differ with regards to secundary aspects. What is more, coalitions can evolve over time, as the notion of policy-oriented learning underlines. Fourth, it would be wrong to suggest that the ACF can be applied to the entire field of EU media policy at once. For one, the field of EU media policy is very wide, emcompasses different subdomains, cutting across different coalitions, etc. Rather, an ACF analysis of different subdomains could be aggregated to come to generalizable conclusions on EU media policy as a whole. Second, both the position of an actor in a coalition and its force in a network may depend on the specific issue at hand. Stakeholders active in one media policy sub-area (e.g. public service broadcasting) may differ considerably from actors involved in another area (e.g. electronic communications, film support, advertising rules). Some actors within the broad area of media policy may limit their activities to one specific issue (e.g. local radio), while others can be seen to operate in many different sub-areas. One stakeholder can adhere to different (even opposing) views and positions and its position and influence in the coalition can differ depending on the issue. For instance, while Flemish public service and commercial broadcasters were shown to hold opposing views regarding the position of public service broadcasting in European media markets, they hold similar views and try to influence EU policy in the same direction when it comes to the position of distribution networks and providers within that same market. Fifth, ACF analyses should not obliterate the fact that the existence of similar or even identical stakeholder coalitions at the European level can result in different outcomes in different Member States, as both subsidiarity and path dependency also play a key role in Member States translation and implementation of EU media policy. In other words: process and outcome are not identical, but separate stages of policy making. A good example thereof is the Flemish ex ante test for significant new public broadcasting services (Van den Bulck, 2011). Although, similar to Germany, complaints of commercial competitors with the European Commission resulted in the adjustment of the Flemish media decree to include such ex ante test, different from Germany no actual test has so far been set up and implemented, a stand-still that can be ascribed to the specifics of the Flemish media policy environment (cf. Van den Bulck & Moe, 2012; Donders, 2012). The different interpretation of key notions (like editorial responsibility, television-like) of the Audiovisual Media Services Directive by different national media regulators is another case in point. The latter suggestion of path dependency of individual Member States points to the fact, that while ACF is different from, but not necessarily excludes “alternative views of EU policy processes as one dominated by inter-institutional competition” (Carammia, 2009, p. 3), as the exercise of Engel (2007) to incorporate both new-institutional and neo-functionalist theories into the ACF model indicate. Other issues that require further attention as they do not neatly fit the ACF include the diverse roles of certain policy actors. Most notably we can refer to the European Commission that at times serves as a policy venue (e.g. for stakeholders to file a complaint), at times as a policy broker (negotiation between different coalitions) and an actor in its own right. While this does not necessarily refute the model as such, this does require further analysis. Similar, with its focus on beliefs and networks, the model is not strong on identifying and explaining the allocation of power. However, even if the model proves not to be a watertight explanation of the policy process, it can still prove an heuristic tool, a “useful ordering framework for identifying important variables and relationships” (Sabatier, 1998b, p. 120), a contribution that should not be underestimated if one seeks to gain scientific understanding of the complex web of actors, instruments and ideas that is EU media policy. References Armstrong, M. and Weeds, H. (2007) ‘Public Service Broadcasting In the Digital World’, pp. 81-149 In: P? Seabright and J. von Hagen (eds) The Economic Regulation of Broadcasting Markets: Evolving Technology and Challenges for Policy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Bardoel, J. (2009) ‘Media Policy Between Europe and the Nation-State: The case of the EU Broadcast Communication 2009’, paper presented at the ECREA Law and Policy Section Conference, Zurich, November. Bardoel, J. and Lowe, G.F. (2007) ‘From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media: The Core Challenge’, pp. 7-26 in G.F. Lowe and J. Bardoel (eds.) From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media RIPE@2007, Göteborg: Nordicom. Barnett, S. (2006) ‘Public Service Broadcasting: A Manifesto for Survival in the Multimedia Age. (A Case Study of the BBCs New Charter)’, paper presented at the RIPE@ conference, Amsterdam, November. Bennett, T. (2006) ‘Theories of the Media, Theories of Society’, pp. 11-29 in M. Gurevitch; T. Bennett, J. Curran and J. Woollacott (eds.) Culture, Society and the Media. London: Routledge. Brugha, R. and Varvasovszky, Z. (2000) ‘Stakeholder Analysis: A Review’, Health Policy and Planning, 15 (3): 239-46. Carboni, N. (2009) ‘Advocacy Groups in the Multilevel System of the European Union: A Case Study in Health Policy-Making’, Observatoire social eruopeén research paper 1 (November), 35 pp. Carammia, M. (2009) ‘What Advocacy Coalition in the EU? The Determinants of Coalition Behaviour in EU Immigration Policy-Making’, paper presented at the 59th Political Studies Association Annual Conference, University of Manchester, 7-9 April.2). Collins, R. (1994) Broadcasting and Audio-Visual Policy in the European Single Market. London: John Libbey. Collins, R. (2011) ‘Public Value, the BBC and Humpty Dumpty words – does public value management mean what it says?’, pp. 49-59 in K. Donders and H. Moe (eds.) Exporting the Public Value Test: The Regulation of Public Broadcasters’ New Media Services Across Europe. Gothenburg: Nordicom. Donders, K. and Pauwels, C. (2008) ‘Does EU Policy Challenge the Digital Future of Public Service Broadcasting? An Analysis of the Commission’s State Aid Approach to Digitization and the Public Service Remit of Public Broadcasting Organizations’, Convergence, 14(3): 295-311. Donders, K. & Pauwels, C. (2010) ‘The Introduction of an Ex Ante Evaluation for New Media Services: Is “Europe” Asking for It, or Does Public Service Broadcasting Need It’, International Journal of Media and Cultural Politics, 6(2): 133-148. Donders, K. and Moe, H. (eds) (2011) Exporting the Public Value Test: The Rgulation of Public Broadcasters’ New Media Services Across Europe. Götenborg: Nordicom. Donders, K. (2012). Public Service Media and Policy in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Dudley, G. and Richardson, J. (1999) ‘Competing Advocacy Coalitions and the Process of “Frame Reflection”: A Longitunidnal Analysis of EU Steel Policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 6: 225-248. Engel, F. (2007) ‘Analyzing Policy Learning in European Union Policy Formulation: The Advocacy Coalition Framework Meets New-Institutional Theory’, Bruges Political Research Papers, 5 (November), 26 p. Fischer, F. (2003) Reframing Policy Analysis: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Freedman, D. (2008) The Politics of Media Policy, Cambridge: Polity Press. Freeman, G.P. (1995) ‘National Styles and Policy Sectors: Explaining Structured Variation’, Journal of Public Policy, 5 (4): 467-96. Garnham, N. (1990) Capitalism and Communication: Global Culture and the Economics of Information. London, Sage Publications. Güg, O.C. (2009) ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework Goes to Europe: An American Theory and its Application Across the Pond’, Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the Political Studies Association, Manchester, April. Haas, P. (1992) ‘Introduction: epistemic communities and international policy coordination’, International Organization, 46 :1, 1-35 Hansen, A., Cottle, S., Negrine, R. and Newbold, C. (1998) Mass Communication Research Methods, London: MacMillan. Harcourt, A. (2005) The European Union and the Regulation of Media Markets. Manchester/New York: Manchester University Press. Howlett, M. (2004) ‘Administrative Styles and Regulatory Reform: Institutional Arrangements and their Effects on Administrative Behaviour’, International Public Management Journal, 7 (3): 317-33. Humphreys, P. J. (1996) Mass Media and Media Policy in Western Europe. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Jacobowicz, M. (2007) ‘Public Service Broadcasting in the 21st Century: What Chance for a New Beginning?’, pp. 29-50 in G.F. Lowe and J. Bardoel (eds.) From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. Göteborg: Nordicom. John, P. (2003) ‘Is There Life After Policy Streams, Advocacy Coalitions, and Punctuations: Using Evolutionary Theory to Explain Policy Change?’, The Policy Studies Journal, 31 (4): 481-98. Kingdon, J. (1995) Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, Boston: Little Brown. Lindquist, E.A. (2001) Discerning Policy Influence: Framework for a Strategic Evaluation of IDRC-supported Research, Victoria (BC): University of Victoria. Online. Available at http://www.idrc.ca/uploads/userS/10359907080discerning_policy.pdf (accessed 17 November 2010). McQuail, D. (2003) Media Accountability and Freedom of Publication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Mitchell, R., Agle, B. and Wood, D. (1997) ‘Towards a Theory of Stakeholder Identification: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts’, Academy of Management Review, 22 (4): 853-86. Moe, H. (2011) ‘Defining Public Service Beyond Broadcasting: The Legitimacy of Different Approaches’, International Journal of Cultural Policy 17 (1): 52-68. Parker, R. and Parenta, O. (2008) ‘Explaining Contradictions in Film and Television Policy: Ideas and Incremental Policy Change through Layering and Drift’, Media, Culture and Society, 30 (5): 609–22. Pauwels, C. & De Vinck, S. (2007), ‘De openbare omroep in nauwe schoentjes? Een blik op de impact van het liberaliseringsbeleid van de EU’, Publieke televisie in Vlaanderen: Een geschiedenis (eds. A. Dhoest & H. Van den Bulck), Gent: Academia Press, pp. 133-166. [Public Service Broadcasting In Tight Shoes? An Insight into the impact of the EU’s Liberalisation Policy – Public Television in Flanders: A History] Prell, C., Hubacek, K. and Reed, M. (2009) ‘Stakeholder Analysis and Social Network Analysis in Natural Resource Management’, Society and Natural Resources, 22 (6): 501-18. Pross, P. (1986) Group Politics and Public Policy, Toronto: Oxford University Press. Quaglia, L. (2008) ‘Setting the Pace? Private Financial Interest and European Financial Market Integration’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 10: 46-64. Radaelli, C.M. (1999) ‘Harmful Tax Competition in the EU: Policy Narratives and Advocacy Coalitions’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 37: 661-682. Ridinger, M. (2009), ‘The Public Service Remit and the New Media’, Iris, Legal Observations of the European Audiovisual Observatory, 6: 12. Sabatier, P.A. (1998a) ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Revisions and Relevance for Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy, 5 (1): 98-130. Sabatier, P.A. (1998b) ‘An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein’, Policy Sciences, 21: 129-168. Sabatier, P.A. (2007) Theories of the Policy Process (2nd ed.de.) Boulder (CO): Westview Press. Sabatier, P.A. and Jenkins-Smith, H. (1993) Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach, Boulder: Westview. Sabatier, P.A and Jenkins-Smith, H. (1999) ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Assessment,’ pp. 117-66 in P.A. Sabatier (ed.) Theories of the Policy Process, Boulder: Westview. Sabatier, P.A. and Weibles, C.M. (2007) ‘The Advocacy Coalition Framework: Innovation and Clarification’, pp. 159-220 in P. Sabatier (eds.) Theories of the Policy Process. Boulder (CO): Westview Press. Siebert, F., Peterson, T. and Schramm, W. (1956) Four Theories of the Press: The Authoritarian, Libertarian, Social Responsibility and Soviet Communist Concepts of What the Press Should Be and Do. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Smith, P. and Steemers, J. (2007) ‘BBC To the Rescue: Digital Switchover and the Reinvention of Public Service Broadcasting in Britain’, Javnost – The Public 14 (1): 39–56. Soltész, U. (2010), ‘Tighter State Aid Rules for Public TV Channels’, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, 1 (1): 32-36. Tosics, N., Van de Ven R. & Riedl, A. (2008), ‘Funding of public service broadcasting and State aid rules – two recent cases in Belgium and Ireland’, Competition Policy Newsletter, 3: 81-84. Van den Bulck, H. (2001), 'Public Service Broadcasting and National Identity as a Project of Modernity', Media, Culture and Society, 23 (1): 53-69. Van den Bulck, H. (2007) ‘Old Ideas Meet New Technologies: Will Digitisation Save Public Service Broadcasting (Ideals) from Commercial Death?’, Sociology Compass, 1 (1): 28-40. Van den Bulck, H. (2008) ‘Can PSB stake its claim in a media world of digital convergence? The case of the Flemish PSB management contract renewal from an international perspective’, Convergence, 14 (3): 335-50. Van den Bulck, H. (2011) ‘Ex Ante test in Flanders: Making Ends Meet?’, pp. 155-63 in K. Donders and H. Moe (eds.) Exporting the Public Value Test: the Regulation of Public Broadcasters’ Media Services Across Europe, Göteborg: Nordicom. Van den Bulck, H. (2012) ‘Towards a Media Policy Process Analysis Model and Its Methodological Implications’, pp; 217-232 in M. Puppis and N. Just (eds.)Trends in Communication Policy Research: New Theories, Methods and Subjects, Bristol: Intellect. Wallace, H., Pollack, M.A. and Young, A.R. (2010) Policy Making in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Warleigh-Lack, A. and Drachenberg, R. (2010) ‘The Policy Making in the European Union’, pp. in M.Cini and N. Perez-Solorzano Borragan (eds.) European Union Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Weible, C.M. (2007) ‘An Advocacy Coalition Framework Approach to Stakeholder Analysis: Understanding the Political Context of California Marine Protected Area Policy’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 17 (1): 95–117. Weible, C.M., Sabatier, P.A. and McQueen, K. (2009) ‘Themes and Variations: Taking Stock of the Advocacy Coalition Framework’, Policy Studies Journal, 37 (1): 121-40.