reading and questions: aquatic biomes and ecosystems

advertisement

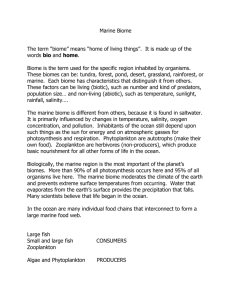

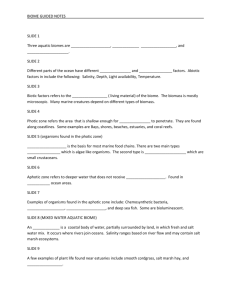

READING AND QUESTIONS: AQUATIC BIOMES AND ECOSYSTEMS The aquatic biomes are the water ecosystems. They include the freshwater (or inland) biome, saltwater (or marine) biome, and estuaries. (An estuary is a transitional area where a river flows into the ocean; it has mixed fresh and saltwater called brackish water.) These biomes support more organisms that do the land biomes. Organisms vary according to whether they are adapted to fresh or saltwater, warm or cold water, quiet or turbulent water, and the presence or absence of light. Other abiotic factors that affect the kinds of organisms found in the aquatic biomes are amounts of oxygen and carbon dioxide dissolved in the water and the availability of organic and inorganic nutrients. In both salt and freshwater, free-drifting microscopic organisms, called plankton, are important components of the biome. Phytoplankton are photosynthesizing algae found near the surface of the ocean; they only become noticeable when they reproduce to the extent that a green scum or red tide appears on the water. Zooplankton are organisms that feed on the phytoplankton. FRESHWATER BIOMES Freshwater biomes can be divided into two types — standing water (lakes and ponds, swamps, marshes and bogs) and running water (streams and rivers). The volume of water in these biomes is much smaller than that of the marine biome. As a result, the temperature variations are larger. Organisms living in freshwater must be able to adapt to greater seasonal variations than those living in the ocean. They also have the problem of maintaining water balance. In a freshwater environment, water enters living cells by osmosis. (Osmosis is the movement or diffusion of water molecules through a semipermeable membrane from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration.) Freshwater organisms usually need a mechanism for removing excess water by active transport. The contractile vacuoles of the ameba and paramecium are examples of such mechanisms. Lakes. Lakes have three layers of water that differ as to temperature. In summer, the upper surface layer is warm, the middle layer has an abrupt drop in temperature, and the lowest layer is cold. This difference in temperature prevents mixing; the top layer lacks nutrients found in the lowest layer, and the lowest layer lacks oxygen found in the top layer. Some mixing does occur, however, during the fall when the top layer cools and again in the spring when the top layer warms; phytoplankton growth is most abundant at these times. Phytoplankton, especially algae, are the main producers of the lake ecosystem. Lakes can be divided into three life zones: the littoral zone is closest to the shore, the limnetic zone forms the sunlit body of the lake, and the profundal zone is below the level of light penetration. Aquatic plants are of four types: (1) emergents, like cattails and bulrushes, which are rooted in the shallow littoral zone of the lake; (2) surface plants, such as waterlilies and pondweeds; (3) watermilfoils, which are underwater plants; and (4) phytoplankton, such as algae and diatoms, which are microscopic drifting (pelagic) plants. Nonproducers of the lake ecosystem are divided into five groups according to their habitats: (1) zooplankton, which are very small animals like rotifer, copepods and water fleas, that feed on phytoplankton; (2) surface insects, like the water strider and water scorpion, that can literally walk on water; (3) subsurface-dwelling insects, like the whirligig beetles and mosquito larvae, that prefer a location just beneath the surface of the water; (4) free-swimming organisms called nekton, including fish, diving beetles and water boatmen, frogs, turtles, snakes and salamanders; and (5) bottomdwelling animals called benthos, such as crayfish, hydra, snails, clams, worms and many kinds of insect larvae. Rivers and Streams. At first, rivers and streams have rapidly flowing water as they move down out of the mountains. In fast-moving streams, the bottom is made of rocks and gravel. Here insect larvae and water plants are adapted to clinging to rocks as the water passes by. Most organisms are found in calmer, shallow areas near the banks of the stream. Here, algae grow on rocks, and there are many insects and insect larvae. Fish and microscopic floating algae are found both in running water and in the calmer pools. As the river nears the ocean, water flows much slower. Where streams are slow-moving, muddy sediment accumulates on the bottom. Plankton can now accumulate, and the community begins to resemble that of a lake or pond. Freshwater Inland Wetlands: Marshes, Swamps and Bogs. Wetlands are areas where water is the primary factor controlling the environment and the associated plant and animal life. These habitats occur where land is covered by shallow water that may be up to 2 m deep or where groundwater is at or near the surface of the land. Most wetlands are dominated by hydrophytes, or wetland plants; hydrophytes can tolerate various degrees of flooding (or living in fluctuating water levels) and soils that are distinctly different from those of dry, upland areas. Wetlands support many types of plants and animals and are important nesting sites for water birds and migrating bird species. Marshes. Marshes are characterized by soft-stemmed herbaceous plants such as cattails and pickerelweed. These plants, called emergents, grow with their stems partly in and partly out of the water. Shallow marshes are those with up to 15 cm of water; deep marshes have as much as 60 cm to 1 m of water. In the deeper marshes, floating and submerged aquatics — such as waterlilies, pondweeds and carnivorous bladderworts — may be closely associated with cattails, arrowheads and other emergents common in shallow areas. Seasonal fluctuations in the water level may occur: water may rise in the spring and recede somewhat in drier periods; some marshes dry out completely for a few months. Some marshes begin as shallow lakes and depressions that gradually fill in with decomposed vegetation. Others occur in the shallow water along the edges of lakes and rivers. Swamps. Unlike marshes, swamps are dominated by woody plants — namely, trees and shrubs. Some are forested with hardwood trees like red maple, gums and ashes; others by evergreens such as cedars, firs and spruces. In the Northeast, swamps dominated by red maple are most common. Beneath the maple, a variety of wetland shrubs, including highbush blueberry, spicebush and sweet pepperbush, may be present. On the forest floor, which is periodically flooded, skunk cabbage is the first plant to appear in the spring, followed by marsh marigolds, orchids and cardinal flowers. Willows, alders, shrubby dogwoods and buttonbush form shrub swamps. Some of these shrub wetlands are relatively permanent; others are transitional and will eventually be replaced by forested wetlands. Some wooded swamps develop from marshes, while others originate directly in poorly drained depressions. Swamp soils are saturated during the growing season, and standing water (from 5 cm to more than 30 cm deep) is not uncommon at certain times of the year. In both marshes and swamps, highly organic soils commonly form a black muck. The underlying mineral soils are usually fairly close to the surface. Bogs. Some of the most interesting wetlands in North America are bogs. They occur primarily in formerly glaciated areas of the Northeast, the north-central states and Canada. Bogs are peatlands, usually lacking an overlying layer of mineral soils. The peat is formed by the building up and gradual decomposition of plant material; this accumulation is especially favored in highly acidic, poorly drained areas where bacteria and other decomposers cannot thrive. Peat forms a floating mat of vegetation over water, and may accumulate in deposits of 7 m to 14 m thick. Bogs often develop in deep glacial lakes. They are characterized by evergreen trees and shrubs, and are often blanketed with a carpet of sphagnum moss. Typical bog shrubs include leatherleaf, bog rosemary, Labrador-tea, sheep laurel, cranberry, and bog laurel. Also present are insectivorous plants, such as sundews and pitcher plants, orchids, larch and black spruce. Bogs offer an unusual source of information for biologists: the underlying peat preserves a record, in the form of fossil pollens, of the kinds of plants that have grown in the area over the last 10,000 to 15,000 years. MARINE BIOMES Since all the oceans of the earth are interconnected, they are said to form a single marine, or saltwater, biome. Conditions and life forms vary from one region of the marine biome to another but without the clearcut differences of the terrestrial biomes. The marine biome covers more than 70 percent of the earth’s surface. Because of the heat capacity of water, the oceans absorb solar heat energy during warm seasons and hold it during cold seasons. As a result ocean temperatures remain fairly stable, though of course, deep areas are much colder than shallow ones. The oceans also have a stabilizing effect on average temperatures of land areas. Temperatures on the earth would vary much more than they do if the oceans did not exist. The aquatic environment of the oceans is stable in other respects too. In any given region (with the exception of estuaries), the supply of nutrients and the concentration of dissolved salts remain relatively constant although they vary from region to region. Although temperatures remain fairly constant in any given part of the marine biome, there is variation with latitude. Ocean temperatures vary from near 0°C in the polar regions to 32°C near the equator. The oceans can be divided into several major life zones: the intertidal zone (including estuaries), the neritic zone, and the open sea (or oceanic) zone. Intertidal Zone. The intertidal zone is the most difficult zone for marine organisms to live in. It is the area along the shoreline that is covered by water at high tide and uncovered at low tide. Organisms in this zone are adapted to periodic exposure to the air. Crabs prevent dehydration by burrowing into sand or mud. Clams, mussels and oysters filter plankton from the water during high tide, then retreat into their shells at low tide. These animals are also adapted to the force of waves crashing onto the shore. Sea anemones cling to rocks with a muscular basal disk. Sea stars gain footing with the aid of tube feet. The streamlined shape of most chitons and bivalves helps protect these mollusks from the pounding waves. Various types of seaweeds — red and brown algae — are abundant in this zone. Estuaries. An estuary is an intertidal habitat found throughout the world where freshwater rivers and streams flow into the sea. Mixed saltwater and freshwater is called brackish water. Examples of estuarine communities include bays, mud flats and salt marshes. Organisms living in an estuary must be able to withstand constant mixing of waters and rapid changes in salinity (amount of salt) and temperature. Also, organisms are periodically exposed to the air during low tide. For organisms that are suited to the estuarine environment, there is an abundance of nutrients. An estuary acts as a nutrient trap because the tides bring nutrients from the sea and at the same time prevent the seaward escape of nutrients brought by the river. In addition, the shallow waters ensure plenty of light, and photosynthesis takes place at all levels. Because of this, estuaries produce much organic food. The abundance of aquatic plants supports many types of fishes, shrimps and crabs. Several species of birds use estuaries for nesting, feeding and resting. Although only a few small fish permanently reside in an estuary, many fish begin their lives in estuaries. It has been estimated that well over half of all marine fishes develop in the protective environment of an estuary, which explains why estuaries are called the “nurseries of the sea.” Even so, many estuaries are becoming victims of pollution because of construction and development along the seacoast and pollution of our rivers. Neritic Zone. Marine life is most concentrated above and on the continental shelf in the neritic zone. This zone extends over the continental shelf from the low tide line to a depth of about 200 m. Here, seaweed, after it is partially decomposed by bacteria, is a source of food for benthic clams, worms and sea urchins, which are preyed on by starfish, crabs and brittle stars, all of which are, in turn, eaten by bottom-dwelling fish. More important, the shallow, sunlit neritic waters, which receive nutrients from the sea and estuaries, produce abundant phytoplankton that grow larger than they would in the open sea. The phytoplankton provide food for zooplankton. These, in turn, are food for the commercial fishes — herring, cod and flounder, for example. Coral Reefs. Coral reefs are areas of biological abundance found in the neritic zone in shallow, warm tropical waters that have a minimum temperature of 21°C. Coral reefs occur only in tropical waters because they form their exoskeletons of calcium carbonate, which will dissolve in cool waters. Corals do not occur individually; rather, they form colonies. Corals are not found at depths below 200 m because they provide a home in their body tissues for a microscopic dinoflagellate called zooxanthellae, a type of algae, which must have light to grow. This is a mutualistic relationship because the zooxanthellae live off the waste products (carbon dioxide, nitrogen compounds and phosphorus) of the cells of the coral animal and, at the same time, release nutrients through photosynthesis to the host coral. Without the zooxanthellae, the coral dies. A coral reef is densely populated with animal life, including butterfly fish, damsel fish, clown fish, sturgeon, sponges, sea squirts, fan worms, barracuda, crabs, sea urchins, shrimps, sea anemones, sea stars, moray eels, sharks, rays and many others. Open Sea Zone. The open sea zone, which includes 90 percent of the ocean waters, is not very productive because the surface waters are nutrient poor. Animals of the oceanic zone feed primarily on sinking plankton and detritus (dead organisms). Few organisms live between 200 m and 2000 m in the bathyal zone. There simply is not enough food to support a large community of organisms. Most of the bathyal zone has no bottom, so no benthic organisms live here. Also, since it is below the photic zone, no plants grow here either. Abyssal Zone. Organisms living below 2000 m are called abyssal organisms and are some of the strangest on earth. Deep-sea fish have slow metabolic rates and reduced skeletal systems that are adaptations to near-freezing temperatures and tremendous pressure. Typical adaptations are large jaws and teeth and expandable stomachs to accommodate any prey that they can catch at these depths. Many organisms in the abyss are bioluminescent — that is, they are able to produce light within their own bodies. Even more unusual organisms inhabit thermal vent communities. Near these areas seawater and sulfur gases seep through vents in the earth’s crust. These hot springs, rich in minerals and often exceeding 700°C, support about 200 species of bacteria in the surrounding area. The bacteria are chemosynthetic — that is, they manufacture food with chemical energy rather than with energy from the sun! Most convert sulfur compounds to usable energy. An assortment of unique clams, crabs and worms feed on these bacteria. No plants reside in the abyssal zone since plants need light to survive. QUESTIONS: Answer the following questions using complete sentences, or read and prepare (take notes in your composition book) for the HW Starter. 1. State two examples each of benthos, plankton and nekton. 2. In what ways are the plant and animal life of streams different from those of lakes? 3. Explain why temperature variations (from season to season) are larger in freshwater biomes; like lakes, than in the marine biome like oceans. 4. In what ways are conditions for marine algae that live in the intertidal zone different from those for marine algae in the neritic zone? In what ways are they similar? 5. Describe what is unique about the ecosystem of sea vents in the abyssal zone.