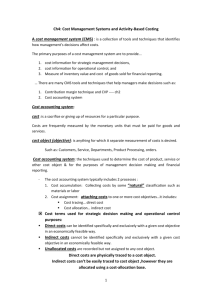

CHAPTER 5

advertisement