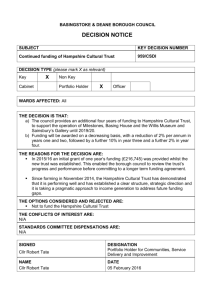

Infrastructure Synopsis 1015kb

Synopsis of Commissioned Evidence

Infrastructure Hearing

1 Section A : Principal Topics - Infrastructure

1.1

Water

1.1.1

Water Resources – Environment Agency

Water resources in Hampshire are based on groundwater stored in the chalk aquifer of the Hampshire Downs and replenished every year by winter rainfall. Hampshire’s water resources are historically resilient; however, they are now at risk from:

increased abstraction associated with: population growth, new development, rising personal consumption;

changes to groundwater recharge and river flows caused by climate change; and

environmental requirements of designated rivers and wetlands.

There is a risk that lower flows in summer will offer less dilution of effluent from sewage treatment works and contaminants from diffuse pollution. The use of grey water has associated health risks and environmental impacts and is not recommended.

The Code for Sustainable Homes provides a framework for house building practice which includes standards for water consumption at 120, 105 and 80 litres of each individual's use known as per capita consumption (pcc). Currently Hampshire’s population uses on average well in excess of these standards.

Water neutrality (no net increase in water consumption) could be achieved through further efforts on water efficiency. A consistent standard of 105 litres pcc for new development across Hampshire will help maintain Hampshire’s water resources.

1.1.2

The Future Of Water Resources In South East Hampshire And West

Sussex – Portsmouth Water

The Company's principal sources of water are derived from the South Downs Chalk via wells and boreholes, some from natural springs and a small proportion from river abstraction.

Portsmouth Water’s Water Resources Plan incorporates a review of the availability of its resources and forecast demands for the next 25 years this was last carried out in 2004. Commercial demands have been falling over many years and this trend is expected to continue as less manufacturing takes place in the UK. Total Demand from domestic sector is expected to rise partly due to the rise in population and households, and also because of a significant rise in pcc.

Comparing Supply and Demand Forecasts for the period through to 2030, it is apparent that during critical periods supply would fall short of demand. By 2019/20 the Company would need frequent hosepipe bans and in a peak demand dry summer of a drought year much more stringent measures might be needed. Portsmouth Water have developed a long term plan to alleviate pressures on demand.

The solution which was adopted incorporates a twin-track approach – generating new resources and improving efficiencies – the majority of which are not needed until after 2015 when the supply/demand deficit is likely to occur and incorporates a package of measures which ensures a positive

Supply/Demand surplus for the Company and its customers.

1.1.3

Water and Sewerage Needs – Thames Water

This paper discusses the potential effects for the water industry of SERPLAN’s predicted levels of housing growth on water resources, sewage treatment and the environment. The need for sustainable development with the competing pressures of water resource limitation, changing regulation, increasing demand and the environment are discussed. Thames Water describes a range of measures aimed at managing the demands of customers consistent with achieving sustainable growth.

Basingstoke is used as a wastewater case example, highlighting pressures on Thames Water in fulfilling the sewerage undertaker’s statutory duties. Basingstoke is located at the watershed of the River

Loddon in the Thames Basin and the southern groundwater catchments of the Rivers Test and Itchen.

There are strict limits on dilution of sewerage effluent from the sewage treatment works. The River is a designated a Sensitive Area (Eutrophic). Population predictions for Basingstoke exceed the threshold for which the River Loddon can provide.

Thames Water faces difficult decisions on how to deal with Basingstoke’s waste water and need to explore measures such as pumping sewerage to different catchments further downstream.

1.2

Built Environment

1.2.1

Climate Change implication on the Built Environment - Arup

This paper looks at the implications of climate change on the built environment in Hampshire.

Climate change is predicted to cause higher temperatures, flood risk, water quality and ground stability problems that threaten to destabilise aspects of the built environment. There is a particular focus on the implications of higher temperatures which are predicted to exceed 40°C in Hampshire by 2080 resulting in buildings overheating to levels that pose risks to human health and welfare especially for vulnerable members of the community such as the elderly. The paper suggests that scope exists to modify urban micro climates through:

reducing Solar Absorption of Materials;

reducing Solar Absorption through Improved Urban Design;

reduce Frictional Losses of Wind Energy through Urban Geometry;

enhance Evaporative Cooling through the Incorporation of Water Features;

strategic Green Space Provision;

encourage Green Roofs; and

complimentary Low Carbon Building Services to Assist Cooling.

Whilst a number of institutional, economic and policy barriers to realising this approach are identified, measures are suggested as to how public authorities can use their powers as catalysts, co-ordinators, procurers and regulators to bring about changes in their urban areas. These include the use of planning powers, whilst also using wider powers as regulators of air quality and urban transport.

Whilst the need to address the existing building stock is acknowledged, it is also recognised that the balance between different types of land uses may need to change in urban areas if these threats are to be successfully managed. Scope may exist to investigate how greenfield/ brownfield land swaps and urban – rural linkages might facilitate aspects of this agenda.

2 Section B : Additional Key Topics - Infrastructure

2.1

Energy

2.1.1

Energy Overview – the Environment Centre

The paper examines the national debate and policy initiatives in Hampshire aimed at reducing climate change impacts and enhancing local security of energy supply. Issues such as energy production, distribution and security of supply are key to Hampshire, especially in areas of high vulnerability in terms of energy distribution, such as Hayling island.

The Partnership for Urban South Hampshire are looking to deliver:

100MW of renewable energy by 2026; and

ensure all new residential dwellings deliver at least 10% of their energy needs from renewable sources.

Hampshire has a number of options available to diversify energy production and supply including: biomass, combined heat and power, and micro generation.

2.1.2

Energy Provider – Utilicom

Utilicom are a leading provider of District Energy Services (DES) in the UK. DES are usually community based projects providing electricity, hot water for heating and frequently, chilled water for air conditioning (this is known as Trigeneration). The efficiency of

DES is often as high as 85% to 90% compared to conventional power stations at approximately 35%. These efficiencies are usually achieved through the use of Combined Heat and Power

(CHP) generators providing electrical power and recovering the heat from lubricating fluids, cooling fluids and exhaust gases.

While many CHP DES are currently gas powered they have the flexibility of being upgraded to Integrated Energy Systems which use alternative energy sources such as biomass. For example,

Southampton uses Geothermal Energy and CHP and will be adding a bio-mass boiler using woodchip fuel late in 2007.

2.1.3

Biofuels – Hampshire Rural Pathfinder (HRP)

The paper examines the different types of biofuels which would be most appropriate for

Hampshire including: rape seed oil, biodiesel and bioethonol. While there maybe an economic case for Hampshire to produce biofuels, there are a number of underlying constraints which needs further examination. These limitations include current high fuel duty (regardless of sustainability), a lack of local case examples leading to reluctance from farmers and currently few market opportunities. The paper also highlights some of the wider shortcomings of biofuel production such as reduced food production, increased food prices along with risks to biodiversity.

Further research is needed to make the case for biofuels both economically and environmentally.

However there are a number of measures HCC could take to promote biofuels in Hampshire, including:

creating a local market for biofuels by working together with other public sector bodies to purchase biofuel;

considering biofuel tenders for HCC’s diesel contract renewal; and

using biofuels to replace diesel in heating boilers at HCC.

2.1.4

Future Energy Solutions – Southampton University

Microgeneration is the generation of heat or electricity by individual buildings or small groups of buildings. Thermal, electrical and combined heat and power (CHP) technologies are discussed and best practice used as examples. A comparison of a range of micro generation technologies in terms of cost

and environmental benefit per £ of capital investment shows that micro-CHP potentially offers the best and photovoltaic (PV) the poorest CO

2

savings and economic return on investment.

District-CHP can be applied as tri-generation where electricity, heating and cooling are generated from the same source. With increasingly hotter summers and the need for cooling of commercial spaces, integrated systems using biomass should be investigated because of their environmental as well as the economic benefit of qualifying for the Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs).

A dominant factor in determining energy use, user behaviour, was highlighted through a study of low energy eco-homes. Visible renewables such as PV were shown to help change behaviour. Achieving behaviour change in the work place is more difficult because the consequences of not being energy efficient do not directly affect users. It is important to increase the understanding of users about the principles of buildings and how they work. The study also showed that current electricity metering schemes are not fair to energy efficient eco-homes and policy changes are needed to help address these issues.

The current built environment with poor thermal performance in terms of winter heat loss and summer overheating will struggle to cope with rising temperatures and heat waves due to climate change. Predicted office temperatures will be close to ambient temperatures and strategies such as home working, flexible working to reduce peak occupancy and behaviour change will be needed to reduce difficulties.

2.2

Transport

2.2.1

Transport Overview - Highways &

Transport Policy, HCC

The effects of climate change on the county’s transport infrastructure are likely to be widespread and be both direct and indirect. It will be affected directly in terms of impacts on:

the performance and maintenance needs of the transport assets including selection of construction materials and associated vegetation;

higher levels of “failures” may have to be accepted in future alongside higher levels of contingency planning, as violent storms hit or prolonged dry periods occur; and

prudent expansion of the winter maintenance to cover weather emergencies with forecasting and modelling used to highlight emergency preventative maintenance works

Indirectly, national policies will start to address the future impacts of climate change – some are likely to reinforce the economic led arguments on reducing or halting the growth in car travel through demand management like road pricing.

The County Council will have to make difficult decisions on intervention levels in maintenance and asset management. It will not be possible to cover all eventualities. There are likely to be increased number of incidents and future operations will need to recognise this and plan accordingly. On the wider policy front the County Council will need to weigh its investment decisions carefully in terms of their long term as well as short-term effects. There is an opportunity for the County Council to develop and lead partnerships that promote its corporate objectives within the context of a climate change strategy.

2.2.2

Southampton International Airport – British

Airport Authority (BAA)

Aircraft and engine designs are expected to continue to set new energy efficiency standards (aircraft in 2020 expected to be 50% more efficient than new aircraft in 2000). BAA highlighted that key climate change impacts for Southampton

International Airport are energy usage and building design.

Issues of managing emissions and reducing energy consumption from airport equipment and buildings include:

constant monitoring of energy usage;

more energy efficient lighting systems being introduced, including “intelligent” lighting that adjusts to levels of natural light;

use of an electronic “Building Management System” to heat or cool the building in the most efficient way;

use of thermal imaging to help identify heat losses;

continued investigation into new energy sources (solar power is used for the airport roundabout lighting); and

continued adoption of accredited design practices and latest planning and government policies in future building work standards and climate change awareness.

In addition, the airport has:

a current “Surface Access Strategy” which continues to promote the excellent public transport links to the facility alongside walking and cycling improvements and the airport’s own Staff Travel Plan;

an “Airport Air Quality Strategy” which includes replacing older airside vehicles with more environmentally friendly ones; and

a role to play as part of BAA’s approach to supporting regional action for an open emissions trading scheme.

3 Section C: General Topics – Infrastructure

3.1.1

Emergency Planning – HCC

Hampshire County Council has a duty to prevent and plan a structured and coordinated response to emergencies.

The Hampshire and Isle of Wight Local Resilience Forum

(LRF) Risk Assessment sub-group has identified risks associated with climate change. Existing plans do not meet the requirements of the scale of involvement suggested by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat.

Further work is necessary to gauge climate change effects on Hampshire County Council services and a risk based approach needs to be adopted in assessing the potential impacts of climate change upon emergency planning and HCC services.

3.1.2

Coastal Defence – HCC

More than half of Hampshire’s coastline is defended by man-made structures such as seawalls and embankments, a large number of which are coming to the end of their residual life. The paper examines the short and long term threats and opportunities that a changing climate will have on coastal defences.

Threats include sea level rise and increased storminess which will add additional pressure to these structures putting people and property at risk from flooding and erosion.

At least 55,000 existing dwellings are at risk of flooding (within 5 metres of mean sea level). Hampshire County Council owns and manages nearly 30 coastal landholdings, roads and rights of way.

Impacts include:

loss of assets (e.g. land, buildings etc);

loss of amenity and recreational use;

increased health and safety risks;

coastal squeeze and habitat loss; and

risk of increased pollution.

Hampshire County Council will need to make some difficult decisions to adapt coastal landholdings to climate change.