Complete Ballads Introduction

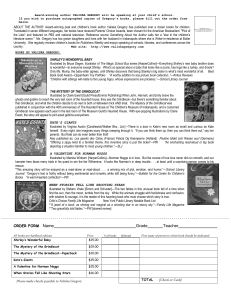

advertisement

PADRAIC GREGORY, COMPLETE BALLADS Introduction Eamonn Hughes Padraic (Patrick Bernard) Gregory 1886 - 1962 When we think about the Irish Literary Revival our tendency is to look to Dublin, but late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Belfast had its own flourishing cultural revival which spread across sectarian and other boundaries. While Irish nationalism, in some degree, was shared by most of the figures associated with it, there was also a strong sense of the need to preserve and celebrate the particular culture of the North: its folklore, music, and language. The result was what could be called Irish nationalism in an Ulster-Scots accent. This was certainly the case in much of the work of Padraic Gregory. The facts, as we know them, of Padraic Gregory’s life are easily enough summarised. He was born in Belfast in 1886, and educated there and in America where his parents emigrated. Gregory himself returned to Belfast to live with aunts while still a boy and completed his education with engineering and architectural apprenticeships, during which he met David Parkhill who would also go on to be a writer. By 1906, Gregory was established in his first architectural practice and worked as an architect for the remainder of his life. For much of that life he was also prolific as a writer, mostly of poetry, though he also published critical work on poetry and painting, anthologies, editions and sacred drama, and was also a dedicated folk-song collector. Despite the fact that he has faded from view to a large extent, many people see his work every day without necessarily realising it. Gregory has left a significant mark in Belfast and beyond. He was the architect of St Anthony’s Catholic Church on the Woodstock Road, of the extensions to Garron Tower in Carnlough when it was converted into St McNissi’s boarding school, and was also responsible for additions to the Dominican Convent on the Falls Road, St Malachy’s Church in Alfred Street, and St Mary’s Chapel, Chapel Lane. The firm of P & B Gregory Architects, which he later set up with his son Brian, was responsible for the design of the Cathedral Church of Christ The King in Johannesburg.1 From this account of his architectural work it is easy enough to see that Gregory was a committed Catholic throughout his life. In turn, the fact that he was also a supporter of Irish nationalism is not that surprising. But getting to grips with Padraic Gregory is not as easy as the bare facts of his life would suggest. There is for a start his forename which exists in a number of different variants (Padraic, Padric, Patric, Padraig, and Pádraic) at least a couple of which he seems to have been happy with since they appeared on the title pages of his books. Gregory seems more secure as a name, but we should still pause on it. He was born and christened Patrick Bernard Gregory, and the change to Padraic (or Padric) would have been a common enough gesture to Irish Information on Gregory’s work as an architect is largely drawn from Paul Larmour, Belfast: an illustrated architectural guide. Belfast: Friar's Bush Press, 1987, and Marcus Patton, Central Belfast: An Historical Gazetteer. Belfast: Ulster Architectural Heritage Society, 1993. On this, and other matters, I am also grateful to Patrick Gregory, the poet’s grandson, who made his own researches available to me. More information about Gregory can be found at http://www.padraicgregory.com. 1 nationalist sentiments, though we should bear in mind that others went much further and a number of his better-known contemporaries took pseudonyms for reasons separate from nationalism, as in the case, for example, of David Parkhill who wrote as Lewis Purcell and Rutherford Mayne, the pen-name of Samuel Waddell. It seems that Gregory’s support for Irish nationalism was largely in the area of culture. He contributed to the 1918 volume Poets of the Insurrection which surveyed the work of Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, Joseph Plunkett and (Gregory’s subject) John Francis MacEntee, whose work he had also edited as The Poems of John Francis MacEntee in the previous year. (Throughout his long political career in the south of Ireland, MacEntee was himself better known as Sean MacEntee.) In that same year, Gregory had himself published a volume of poems, Ireland: A Song of Hope and other poems (1917), and while the sentiment of the title poem (see p. 118 below) is transparent enough, it’s worth noting that the original volume also contains ‘The Healer’, a poem dedicated ‘In memory of my friend Francis Wisely, M.D., who died of wounds received at Gallipoli, Sept. 14th, 1915’. This begins to question whether Gregory’s nationalism was as single-minded as this flurry of attention to the men of 1916 appears to suggest. If there seems to be a faint Yeatsian echo in ‘The Healer’ (of ‘An Irish Airman Foresees his Death’, similarly an elegy for a World War 1 casualty) that too is somewhat misleading for reasons which allow us to begin to understand Gregory not simply as an Irish Catholic nationalist but as someone both narrower and broader than that label would suggest. This is where Gregory the writer begins to be interesting and deserving of more attention than he has received. Sam Hanna Bell’s The Theatre in Ulster (1972) starts with the establishment of the Ulster Literary Theatre. According to Bell, in the autumn of 1902 David Parkhill and Bulmer Hobson returned to Belfast by train from Dublin where they had gone with the aim of getting W.B. Yeats’s agreement to establish a northern branch of the National Theatre Society. Having been rebuffed in some manner by Yeats, Hobson, in frustration, is supposed to have exclaimed ‘Damn Yeats, we’ll write our own plays!’ Regardless of the truth of this story, the foundation of the Ulster Literary Theatre was a crucial event in the often-overlooked Ulster Literary Revival which was not simply a northern branch of the Irish Literary Revival. Though there are obvious points of overlap between the two enterprises – both were committed to an idea of a cultural revival in Ireland – the northern version tended to a satirical view of what was seen as Dublin idealism, and was also rather more attentive to some of the actualities of life in the north. Gregory was very much a part of the Ulster Revival. His first published volume, The Ulster Folk (1912), states as much in its title, and its dedicatees were Lewis Purcell and Rutherford Mayne, who were by this stage (along with Gerald Macnamara) the key dramatists of the Ulster Literary Theatre. If Purcell, Mayne and Macnamara were largely responsible for the satirical edge of the Ulster Literary Revival, Gregory’s ‘Introductory Note’ to The Ulster Folk demonstrates his commitment to the actualities of life in Ulster, and in particular to its language: In the Country districts of Antrim and Down I have collected – during the past few years – the words and airs of many fine old folk-songs, which I hope to publish at some future time, properly arranged, with suitable pianoforte accompaniments, notes, &c. Besides these, I have obtained some fragments – the beginnings, endings, and odd verses of many other songs … (The Ulster Folk, vii) He would eventually and handsomely fulfill the ambition to publish the songs he had collected in the two volumes of Anglo-Irish Folk Songs (Volume 1, with Traditional Airs arranged by the late Dr Charles Wood, 1931; Volume 2, with Traditional Airs arranged by Carl Hardebeck, 1935), but he worried too about the fragments he had gathered. He goes on to explain how he has used these fragments in poems such as ‘Shaun O’Neill’ (23), ‘The Wee Wee Man’ (54) or ‘The Girl That Loved a Fairy’ (59): I LOVE a wee, wee lochrie-man, For he’s a rantin’ Irish man, An’ I’ll dae all I iver can Tae get that wee, wee lochrie-man. I’ll sell my rock, I’ll sell my reel, I’ll sell my Granny’s spinnin’ -wheel, An’ I’ll bring all the goold I can Tae gi’e that wee, wee lochrie-man. I’ll work from dawn till even-dim, I’ll wash, an’ scrub, an’ scour, for him, I’ll shine the delph till all’s nae more, I’ll rid the hearth, an’ brush the floor. O I’ll dae all I iver can, If I get that wee lochrie-man. His notes are partly to avoid the charge of plagiarism (and he comments disparagingly on the habit of others who present such fragments and folk-songs as if they were all their own work), but they also reflect his clear belief that ‘There are many of our old folk-songs worthy of being collected, properly patched, if absolutely necessary, and preserved…’ (x). It is better, in other words, for someone like him to use such fragments (with acknowledgement) rather than run the risk of them being lost. The upshot of this is that his writing, particularly that collected in this volume which is based on the Complete Collected Ballads published in 1935, is largely in what these days is referred to as Ulster Scots or related dialects. He also wrote more linguistically conventional poetry, but it can be rather stilted and overly given to a ‘poetic’ register full of terms which no one ever uses in speech and very few, even in Gregory’s day, use in poetry: ‘and lo’ ‘silvern’, ‘ere’, ‘gentlewise’, ‘oft’. Such terms are not always a problem in his writing, however, since the dialect and historical aspects of much of his poetry, especially the ballads, often provide a context which neutralises the selfconsciously ‘poetical’ nature of such terms. His writing in Ulster Scots is also not without fault: it can, as is often the case with ‘dialect’ writing incline to a soft-focus folksiness, in poems such as ‘The Sweetie-Shop’, or ‘Granny’s Advice’. Like many in his time, Gregory took an interest in language issues, particularly the use of English in Ireland. The Introduction to Modern Anglo-Irish Verse (1914), subtitled ‘An Anthology selected from the work of Living Irish Poets’ contains his most direct statement on language: It would be impossible, in my opinion, to compile a volume of the present dimensions consisting of unimpeachably great poems from the English verse of living Irish writers: I do not even think it would be possible to compile such a book from the work of Irish poets living and dead. For, though Ireland has given to the world the work of many men and women since first the English language was forced on our forebears, not one of her poets, expressing himself in English, can compare with the world’s great masters; and the work of but very few can compare favourably in sublimity of thought, in beauty of expression, or in subtlety of craftsmanship with that of the major English poets. (xii) There is an implicit argument with Yeats here, given the effort that Yeats had put into establishing an English-language literary tradition in Ireland (and Yeats, with only three poems, is by no means the best represented poet in the anthology). Where writers like Yeats or Joyce set out to resolve the problem of language in Ireland at a national or even international level, Gregory moves closer to the regional level, closer to language as he has actually heard it spoken in Ulster. This suggests that Gregory’s way round the problem of language was to use dialect, and to do so particularly in ballad form. If many of his ballads, like his other poems, have a nationalist aspect, they also exemplify the earlier statement about him being both narrower and broader than that label would suggest. His interest in ballads is very much rooted in Ulster but he is also aware of both Scots and English traditions as well: his second collection, Old World Ballads (1913), is divided into Scots, Irish and English sections. His ballads then take many forms and range widely across subjects. If dialect enables him to write outside the difficulties of conventional English for an Irish writer, his ballads in turn, like his folk-song collecting, can let us hear otherwise silenced voices. This is literally the case in ‘A Rebel’s Wife, Kilroot, Co Antrim, AD 1798’: I WAS roped, an’ gagged, an’ cudnae speak, O my heart an’ sowl wi’ loathin’ filled! As my brither’s wife – nae blush on her cheek Standin’ furnenst the bedroom door, Spoke tae the Captain o’ the Yeos who’d killed Her husband, a while before. (And as with all the best ballads, you’ll have to read on to find out what happens next.) There is a tendency in his work to see the other side of things; so a sequence of poems about the heroism of those fighting for Ireland in the Easter Rising of 1916, contains ‘Easter Week (AD 1916)’ which one might expect to be the focus of the sequence, but instead of further celebration of heroism we are given instead a mother’s lament. These examples of voices that we might not normally hear are part of Gregory’s larger project: his work is driven by the need to rescue and record Ulster folk culture in recognisably Ulster voices. This leads to the characteristic combination of the ballad form and the use of Ulster dialects which sees Gregory at his best. The often grim subject matter traditionally found in ballads cuts across the tendency to sentiment and folksiness which can mar his writing. In such ballads, Gregory can hold the attention and supply what one contemporary reviewer called ‘concrete grisliness’. This phrase was used in reference to ‘The Ballad of Mr Fox’, which is Gregory at his best; the reader is propelled through some 500 lines by breakneck narrative, rhythm and rhyme. ‘The Ballad of Mr Fox’ was greeted as special by a number of reviewers on its first appearance in 1913. By the time Gregory included it in his Collected Ballads of 1935, however, the energies of the Ulster Literary Revival had long since dissipated. His Anglo-Irish Folk Songs, the collecting of which seems to have provided his start as a writer, and to have been his major contribution to the Ulster Literary Revival, had been published in two volumes. By the early 1930s, Gregory had turned his hand to religious drama in the shape of Bethlehem and Calvary which were never published, and The Coming of the Magi (1932) which, while by no means giving the devil the best tunes, has an interestingly sympathetic characterisation of Herod at its core; despite this it also has an approving introduction by Cardinal MacRory. Gregory had also by the early 1930s acquired the reputation of being ‘the Irish Poet of Christmas’ as he was called in 1933 and a number of his Christmas Carols and Ballads are included here. In that same year his Selected Poems were edited ‘for use in Schools and Colleges’ by J. J. Campbell of St Malachy’s College. At this stage his writing life seems to come to an end. He would publish a work of criticism on painting, When Painting Was in Glory, 1280-1580, in 1941, and composers continued to set some of his ballads and carols to music. ‘Padraic the Fiddiler’ was set by both John Larchet, director of music at the Abbey Theatre from 1907, and Armstrong Gibbs. Larchet’s version was recorded by John McCormack and the violinist Fritz Kreisler in 1925. Gregory’s Complete Collected Ulster Ballads was published in 1959, just three years before his death. There seems to be a sense of completion in this. Gregory was part of the Ulster Literary Revival and flits in and out of various accounts of the early decades of the twentieth century in the North of Ireland. His part in that Revival was to document an Ulster folk culture, particularly as he found it in Counties Antrim and Down, and he stayed true to that aim even after the revival itself had died away. John Hewitt’s brief mention2 of him implies that he was overshadowed by Joseph Campbell as a lyrical writer and by Richard Rowley as a narrative and vernacular poet, but Hewitt may not in the end be the best judge. We might want to note that Gregory himself could on occasion strike a satirical note as in ‘The Poor Gleaner’. Here, Gregory, by way of a joke at the expense of Yeats’s much more grandiose ambitions in ‘To Ireland in the Coming Times, realistically and modestly acknowledges his own ambition and achievement: Let Moore, Mangan, Davis and Ferguson Be honoured, both now an’ in comin’ times; I only ax folk for tae say o’ me: ‘His love o’ the North folk filled all his rhymes.’ (‘The Poor Gleaner’) I think it’s fair to say that Gregory succeeded in this ambition; as we read these poems we can hear the echoes of Northern voices from a century and more ago. John Hewitt, ‘“The Northern Athens” and After,’ in J.C. Beckett et al., Belfast: The Making of the City. Belfast: Appletree Press, 1988, 71-82, 78. 2