Harvey

advertisement

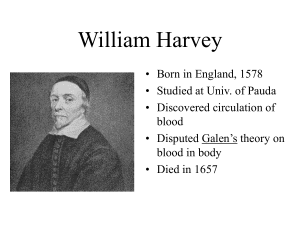

William Harvey was born in England in 1578. He studied medicine at Padua University between 1598 and 1602. He was very interested in anatomy, particularly the work of Vesalius. After leaving university he worked as a doctor at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, and then as a lecturer in anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was also physician to both James I and Charles I. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Where and when was William Harvey born? Where and when did Harvey study medicine and what did he become interested in? What was his first job? What was his second job? What other job did he have? Although Vesalius had proven that some of Galen’s ideas were incorrect, Galen’s explanation of the function of the heart was still accepted. Galen said that blood was made in the liver, and got into the arteries through holes in the septum of the heart. He said that blood was continually being made to make up for the fact that it was used up by the body. 6. Whose explanation of the function of the heart was accepted at this time? 7. Describe this explanation. Like Pare and Vesalius, Harvey believed in the importance of careful observation, dissection and experiments in order to improve his knowledge of how the body worked. In 1615 Harvey began to work on the idea that blood circulated around the body. Around this time, water pumps were invented. This gave Harvey the idea that perhaps the heart worked in the same way as a water pump, and pumped blood around the body. 8. What ideas were important to Harvey? 9. What idea did Harvey begin work on in 1615? 10. What new invention helped Harvey, and how? Harvey wanted to study the body as a living system, so he needed to dissect things which were still alive. He chose to study cold-blooded animals like frogs because their hearts beat slowly. This enabled him to see each separate expansion and contraction of the heart. He also dissected the bodies of dead criminals to ensure that the human heart was the same as that of the live animals he had studied. 11. Why did Harvey need to dissect things that were still alive? 12. Why did he use cold blooded animals like frogs? 13. Why did he then dissect dead criminals? Harvey’s study of beating hearts showed him that the heart was pushing out large volumes of blood. He proved that each push happened at the same time as the pulse which could be felt at the neck and at the wrist. He realised that so much blood was being pumped out by the heart, that it could not be used up and replaced by new blood as Galen had said. This suggested that there was a fixed amount of blood in the body, and that it was circulating. 14. What did Harvey’s experiments show him, and how was this linked to the pulse? 15. How did Harvey know Galen was wrong, and what alternative theory did he give? Harvey now needed to prove his theory. By trying to pump liquids the wrong way past the valves in veins and arteries, Harvey proved that they were all ‘one-way’ systems. This proved his theory that blood flowed out from the heart through the arteries, and it flowed back through the veins to the heart where it was recycled again. He also devised a simple experiment that anyone could use on themselves to prove that blood only flows one way through the veins. By bandaging the upper arm, the valves show up as nodules on the vein. If your finger is pushed along the vein from one valve to the next, away from the heart, the section of vein will be emptied of blood. It will stay empty until you take your finger off. Harvey published his theory of the circulation of blood in his book, On the Motion of the Heart, in 1628. He included a sketch of how to perform this simple experiment, to prove his theory to readers. 16. Describe the first experiment Harvey used to prove his theory. 17. Describe the second experiment Harvey used to prove his theory. 18. When did Harvey publish his ideas, and what was his book called? Harvey’s theory met with opposition because it suggested that if there was a fixed amount of blood in the body, then there was no need for the practice of blood letting. Blood letting was a very common and well respected medical practice, which had been used ever since ancient times, (e.g. in the Four Humours). After his book was published he actually lost patients, as his ideas were considered strange for the time. Despite this, soon after his death, his theory was soon widely accepted. Over the next 300 years his theory was used to build up knowledge of what the blood did in various parts of the body as it circulated. Harvey made a great contribution to medical knowledge, but it was not until the 1900’s that the knowledge was used in medical practices. Medical practices in the Renaissance were not changed by Harvey’s work. Blood letting still continued to be a popular practice, and it was only in the 1900’s that doctors realised the importance of checking a patient’s blood flow by checking their pulse. 19. Why did Harvey’s theory meet with opposition? 20. How did this opposition affect Harvey’s career? 21. How valuable was Harvey’s work to medical practice during the Renaissance? Explain your answer. Factors in Harvey’s success 24. Join up the following statements to provide the factors that enabled Harvey to succeed. HEADS An enquiring attitude Belief in the importance of careful observation, dissection, and experiments. Education Technology Art The role of the individual TAILS The invention of the water pump gave him a new comparison which he could use to think about how the heart could work. Like Vesalius, Harvey used illustrations to prove his points in his book. One famous drawing of an arm showed people how to prove that blood only flows one way. Harvey was a determined individual. He was not be put off by the opposition to his theories, even though he lost many patients because of it. Like Vesalius and Pare, Harvey was not satisfied with existing medical ideas, he wanted to investigate things for himself. Like Vesalius, Harvey observed the body closely, dissected humans and animals, and carried out many experiments to prove his theory beyond reasonable doubt. Like Vesalius, Harvey was a well educated Renaissance man, familiar with the works of the great medical authors, but also educated in the spirit of challenging accepted ideas.