Economic Superpower Sweepstakes: Can China Succeed Where

advertisement

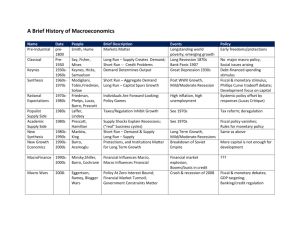

Economic Superpower Sweepstakes: Can China Succeed Where Japan Failed? By Ren Xiang (Paul) Tan University of London (UK): School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Introduction Although close neighbours, throughout history China and Japan competed against each other for dominance in the region. Being different in many respects, the two countries each took a very different path when it came to economic development after World War II. Their divergent political systems would play an influential part in their post-war economic development: at that time Japan became a constitutional monarchy, where its people acquired representation through democratically elected governments, and by contrast China adopted communism after its civil war. Since then, both China and Japan have striven to attain the status of economic superpower. The comparative analysis that follows yields two conclusions (i) while Japan has not yet succeeded in achieving this status, it is unlikely to do so before China due to its lack of resilience, and (ii) between China and Japan, China is better positioned to become a global economic power, not only because of its own resilience to global economic challenges, but also because the underpinnings of its economy. The paper start with a description of Japan’s bid to become a world superpower since the 1970’s and the factors leading to its decline. A comparison is then made to the different economic path China chose to take. The comparison will show that although Japan and China may have similar patterns of economic development, the differences are in China’s favour. 1 Japan: A Promising Start Leads to One Falter after Another From 1970s to the 1980s, Japan enjoyed double-digit growth, above the 2% benchmark, and was being considered as a prospective superpower (Hayashi and Prescott, 2001; Agnese and Sala, 2009). In hindsight, many factors undermined Japan’s bid to achieve that status. strong economic growth in the 1980s, Despite its the effects of deflation, its growing fiscal debt, and a liquidity trap all worked to reduce any flexibility it might have had with its monetary policy, and further tightened its dependency on its Western allies, notably the United States (Bayoumi, 2001). During the 1990s, now known as its ‘lost decade’, Japan’s economy was the worst-performing one among industrialised nations, with its GDP ranging from 1.2 percent down into negative digits (Horioka, 2006). The period of deflation that resulted from this stagnant and negative growth devalued domestic assets even though both government and consumer spending continued to grow. In addition, its unemployment rate began to rise, worsening the decrease in GDP growth. One could argue that the change in work hours, from 44 to 40 hours a week, did not contribute to the decrease in productivity from 1988 to 1993 (Hayashi and Prescott, 2001). This is based on the reasoning that the productivity rate would be offset by increase in employment where the labour input would remain equal, though it reduces the rate of return to capital and also discourages private investments (Fukao and Kwon, 2005). As well, in the early 1990s other developed economies around the world, including superpowers, were in a recession. Overall productivity was beginning to contract and consumer spending levels were dropping. Since Japan’s economic model is export-driven, companies were forced to shrink operations, and national output/productivity was also cut back as a result (Boltho, 1996). To make matters worse during that 2 widespread recession, Japan was hit with its own, and first, recession since the 1970s (Bayoumi, 2001). It is widely accepted that the decline of Japan’s high growth hitherto that began in 1990 is credited to two factors: the burst of the bubble that drove its growth in the 1980s and an unsuccessful attempt by the government to implement a Japanesestyle Big Bang in its domestic financial markets (Reszat, 2003). From 1990 to early 1998, Japan’s growth averaged only ¾ percent per annum, while its output gap declined from a positive 4½ percentage points in late 1990 to a negative 7½ percentage points by early 1998 (Bayoumi, 2001). Some have argued that it was the government’s fiscal and regulatory policies of the time that led to a decrease in, if not a halt to, government spending, and a credit-crunch (Griffin and Odaki, 2009). However, although the government’s fiscal and regulatory policy may have contributed to the drop in investment by the private sector, it was not the cause: Japan’s domestic financial institutions were being stretched, it did not prevent businesses from seeking alternative sources of funds and investments beyond its borders, if they chose, since other financial institutions in the world had the ability to provide financing to them (Hayashi and Prescott, 2001). Aside from the effects of the global recession at the time, the government itself was financially constrained. As a direct result of being heavily in debt, the government was unable to provide stimulus funding, unlike the governments of other industrialized economies, who were able to do so in their respective economies (Bayoumi, 2001; Iida and Matsumae, 2009). Despite the size of Japan’s population and the country’s economic growth between 1970s and 1980s, the global recession, inflation, and fiscal issues all had an indisputable influence on slowing its growth. It would take another decade for it to recover. And if that weren’t enough, the stock and land value to boom that Japan 3 experienced in the 1980s, and the resulting bubble burst compounded by the 1997 financial crisis, have left its financial infrastructure in shambles (Reszat, 2003). China – The Metamorphosis of an Economic Dark Horse into a Galloping Elephant China has undertaken numerous changes to modify its economic structure, from opening up its market to a wide range of domestic reforms, all of which have contributed to its economic growth (Demurger and Berthelemy, 2000; Goodhart and Xu, 1996). These reforms have also enabled China to benefit from rising globalisation. As it began its economic reforms in 1978, China’s GDP averaged 9.7% per year up to 1998, even though its legal and financial infrastructures were not as developed as those of other industrialised countries (Chow and Li, 2002). Despite its economic reforms are still in progress and have yet to mature, the growth of China’s private sector is much stronger than most other domestic sectors as well as those of developed countries (Allen et al, 2005). Even though China, by the nature of its political structure, is a controlled economy, its government has allowed some degree of capitalism to permeate and benefit its economy. There is a considerable spectrum of views in the literature about the actual causes behind the strong economic growth enjoyed by China and rest of East Asian countries (excluding Japan). Still, there is a broad recognition that high-growth Asian economies benefited from selective or strategic government interventions and regulation, which ranged from extreme laissez-faire to extreme regulation (Collins and Bosworth, 1996). China’s growth has also been credited to the incentives offered to attract foreign technology and capital investment (Demurger and Berthelemy, 2000). 4 Although, historically, economic reform has usually been accompanied by a deep decline in output, such as has happened more recently in the economies of Eastern Europe, China has managed a successful transition from a centralised system to a more open and market driven economy, giving its economy in an immediate boost (Boresnztein and Ostry, 1996). In contrast to Japan’s post-war economic path, China’s direction is more promising, for two reasons. First, China has been able to attract direct foreign investment; it was the first nation to do so among the developing economies and the second in the world after the United States. Globally, direct foreign investment has facilitated the transfer of technology from developed to developing countries, effectively narrowing the technological gap between them (Demurger and Berthelemy, 2000). On the other hand, Japan’s post-war experience did not include direct foreign investment, much to its detriment. Second, China has a more diversified group of trading partners than Japan had at the time. During Japan’s post war economic reconstruction, its main trading partners are the United States, Britain and France. In comparison, China is essentially the main nexus for the world’s manufacturing and production facilities (Prasad, 2009). Beyond those advantages, China maintains a tight control over its fiscal policy, and as a result, and it is not as heavily indebted as Japan was at the time. Collins and Bosworth (1996) assert that the high growth rates of the Chinese and other East Asian economies were driven by effective government policies, and their maintenance of high rates of savings and investment. These factors helped ensure China was in a more resilient position when it, like others around the globe, faced the collapse of the global financial markets of 2008-2009 in the wake of the housing crisis. 5 Compare this with Japan, which was vulnerable to the effects of its recession, and from which it could not emerge until a decade later (Hoshi and Kashyap, 2005). China’s response to this last financial crisis was to initiate spending programs to stimulate its economy, while holding down inflation, and preventing deflation. But perhaps most importantly, because China has a strong base of direct foreign investments within its borders, it was able to accumulate substantial domestic and foreign currency reserves (Collins and Bosworth, 1996). This is notwithstanding the other benefits from having encouraged foreign investment, namely the creation of jobs and building of infrastructure, relieving the central government from having to use its own reserves for such investment. Weighing in on the Bets for China It would not be a stretch to suggest that, when Japan’s economy began to surge in the 1980s, it did not go unnoticed by the Chinese, who then initiated their reforms. Japan was attempting to tighten regulation of its own financial sector, while China was going in the oppose direction, fiscal decentralisation (Lin and Liu, 2000; Baskaran and Feld, 2009). Yet the two neighbours have shared a similar pattern of economic growth that is starting out as a small-scale economy to becoming one of the largest in the world. Should one then conclude that China risks the same fate in the face of financial crisis as Japan when it suffered the fallout from the burst of its own economic bubble? Not when factoring in the differences in their respective approaches and economic constituents. China has been largely successful in keeping its inflation rate steady, regardless of the boom in land values that resulted from its economic success, as Japan experienced during the 1980s. It is therefore notable that, at the time as well as today, China’s legal and financial systems 6 were still a ‘work in progress’ and yet to be fully developed (Hasan et al, 2009). In contrast, when Japan experienced its economic boom and bust, its legal and financial structure were much more established (Reszat, 2003). However, China is endowed with three advantages that Japan did not have. First, the fact of having a centralized government enables China to make policy and regulatory changes that may go against market demand and restrict uncontrollable growth. Second, China’s is a two-way economy. On one hand, it exports manufactured goods and products, but on the other it imports investment and advanced technology to develop and sustain its economy. Compare with Japan which, during the 1980s and to some degree today still, remains an export driven and protectionist economy. Third, China is much more diversified in terms of trading partners than Japan was during the 1980s. Beyond that, the size of China’s population cannot be discounted, even with the large income disparities. China will always attract global investment by virtue of its massive domestic market (Fleisher et al, 2009; Woo, 1998). Future Studies & Synthesis Given with such strong prospect of becoming an economic superpower, China currently feels powerful, but it is still weak in terms of economic development. Therefore, it would be beneficial to re-examine China’s legal and financial structure within the coming decade to assess the flexibility and adaptability of its infrastructure to withstand economic typhoons. Nonetheless, with all of its advantages and continuing initiatives, China has positioned itself to reach the coveted status of economic superpower ahead of Japan in the coming decades, and likely sooner than later. 7 References Agnese, P., & Sala H. (2009) The fading 1990’s in Japan: Driving forces behind the unemployment upsurge. [online version]. International Review of Economics and Finance, 18: 428-439 Allen, F., Qian, J., & Qian, M. (2005) Law, finance andeconomic growth in China. [online version] Journal of Financial Economics, 77: 57-116 Baskaran, T., & Feld, L. P. (2009) Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth in OECD Countries: Is there a Relationship? [online version] CESifo Working Paper No. 2721 Category 1: Public Finance Bayoumi, T. (2001) The morning after: explaining the slowdown in Japanese growth in the 1990s. [online version] Journal of International Economics, 53: 241-259 Boltho, A. (1996) Was Japanese growth export-led? [online version] Oxford Economic Papers, 48: 415-435 Borensztein, E., & Ostry, J.D. (1996) Accounting for China’s Growth Performance. [online version] The American Economic Review, 28(2): 224-228 Chow, G.C., & Kui-Wai, L. (2002) China’s Economic Growth: 1952-2010. [online version] Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51: 247256 Collins, S.M., Bosworth, B.P., & Rodrik, D. (1996) Economic Growth in East Asia: Accumulation versus Assimilation [online version] Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1996(2): 135-203 Berthelemy, J-C., & Demurger, S. (2000) Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth: Theory and Application to China. [online version] Review of Development Economics, 4(2): 140-155 8 Fleisher, B., et al. (2009) Human capital, economic growth, and regional inequality in China. [online version] Journal of Development Economics Fukao, K., & Kwon, H.U. (2005) Why Did Japan’s TFP Growth Slow Down in the Lost Decade? An Empirical Analysis of Firm-Level Data of Manufacturing Firms. [online version] REITI Discussion Paper Series 05E-004 Goodhart, C., & Xu, C. (1996) The Rise of China as an Economic Power [online version] National Institute Economic Review, 155: 56-80 Griffin, N.N., & Odaki, K. (2009) Reallocation and productivity growth in Japan: revisiting the lost decade of the 1990s [online version] Journal of Productivity Analysis, 31: 125-136 Hasan, I., Wachtel, P., & Zhou, M. (2009) Institutional development, financial deepening and economic growth: Evidence from China. [online version] Journal of Banking & Finance, 33: 157-170 Hayashi, F., & Prescott, E.C. (2002) The 1990s in Japan: A Lost Decade. [online version] Review of Economic Dynamics, 5: 206-235 Horioka, C.Y. (2006) The causes of Japan’s ‘lost decade’: The role of household consumption. [online version] Japan and the World Economy, 18: 378-400 Hoshi, T., & Kashyap, A. K. (2004) Japan’s Financial Crisis and Economic Stagnation. [online version] Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1): 326 Iida, Y., & Matsumae, T. (2009) The Dynamic Effects of Japanese Macroeconomic Policies: Were There Any Changes in the 1990s? [online version] ESRI Discussion Paper Series No. 209 9 Lin, J.Y., & Liu, Z. (2000) Fiscal Decentralization and Economic Growth in China. [online version] Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49: 1-21 Prasad, E.S. (2009) Is the Chinese growth miracle built to last? [online version] China Economic Review, 20(1): 103-123 Reszat, B. (2003) Japan’s Financial Markets: The Lost Decade. [online version] HWWA Discussion Paper No. 231 Woo, W.T. (1998) Chinese Economic Growth: Sources and Prospects. [online version] The Chinese Economy. London, U.K.: Economica. 10