to read paper - Keating Chambers

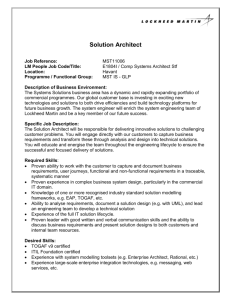

advertisement

THE DESIGNER’S DUTY – TIME FOR REVIEW A paper presented to a meeting of the Society of Construction Law in London on 4th November 2008 Alexander Nissen QC December 2008 151 www.scl.org.uk THE DESIGNERS’ DUTY – TIME FOR REVIEW Alexander Nissen QC Introduction To understand their risk exposure fully, architects, engineers and other construction professionals engaged in design work need to know the extent of their design liability. ‘Extent’ for these purposes means two things: what they are obliged to do, and for how long that obligation continues. By its very nature, design is not a static concept. The notion of design development is well-understood. Sometimes, the need to alter the design exceeds mere development and involves a reappraisal of aspects of the original design concept. On an ongoing project, a variety of matters can occur which require reconsideration of the original design. Sometimes these events can occur after completion. This paper is concerned with the extent of the duty to revisit or review the original design and seeks to examine the following questions in the light of recent developments in case law: 1. What does the duty to review a design comprise? 2. How long does the duty to review a design last? 3. What are the legal consequences of breach of the duty to review a design in the sense of damages claimable? For simplicity, the notional designer selected in this paper is the architect, though the same considerations apply equally to engineers and other construction professionals undertaking design. 1. What does the duty to review a design comprise? It has long been established that an architect has a duty to review his design. The writer has previously analysed the cases which established this principle.1 The Court of Appeal in Brickfield Properties v Newton held that, ‘The architect is under a continuing duty to check that his design will work in practice and to correct any errors which may emerge.’2 This principle has been applied in a number of well known construction cases since. HHJ Stabb QC in London Borough of Merton v Lowe declared himself 1 2 Alexander Nissen, The duty to review a design – is it real or artificial? Const LJ 1997, 13(4), pages 221-6. Brickfield Properties v Newton [1971] 1 WLR 862, CA, per Sachs LJ at page 873F (also [1971] 3 AllER 328). 1 ‘… now satisfied that the architect’s duty of design is a continuing one’,3 while HHJ Newey QC in Equitable Debenture Assets Corporation v William Moss Group stated that, ‘Morgan’s obligation to design International House was not, I think, a once and for all obligation, performed when a complete set of working drawings, which included Alpine’s, was sent to Moss [the main contractor]. Morgan had both the right and the duty to check their initial design as work proceeded and to correct it if necessary.’4 In University of Glasgow v William Whitfield, HHJ Bowsher QC also spoke of the duty to design as ‘a continuing duty.’5 What obligations are comprehended in the duty to review must, in part, depend on what the architect has agreed to do within the envelope of his professional duty. What he has been originally engaged to do must be expected to have an effect on the nature of the continuing duty, if only because the opportunities for review will be so different. In the early cases, the judges still spoke routinely of ‘supervision’ of the project. Thus in Victoria University of Manchester v Hugh Wilson HHJ Newey QC explained the architect’s contractual and tortious duties as: ‘… to exercise the skill and care to be expected of a competent architect in designing the Centre, in supervising its construction and, when and if necessary, reviewing and amending the design.’6 [emphasis added] More recently, it could not be taken for granted that the architect would have undertaken a duty of supervision. In the RIBA standard form conditions of engagement, the word ‘supervision’ has been conspicuously absent for some 25 years. It is true that in some more modern cases like Alexander Corfield v David Grant, HHJ Bowsher QC could still be found referring to ‘supervision’.7 However, that appears to have been based on implied terms of engagement. More typical today would be Consarc Design v Hutch Investments, where the same judge observed that while ‘The older forms of contract required the architect to “supervise”. The more recent contracts including the contract in this case, require the architect to “visit the Works to inspect the progress and quality of the Works”.’8 3 4 5 6 7 8 London Borough of Merton v Lowe (1981) 18 BLR 130, CA, noted in the Commentary, page 133. Equitable Debenture Assets Corporation Ltd v William Moss Group Ltd (1984) 2 Con LR 1, TCC, at page 24. University of Glasgow v William Whitfield (1988) 42 BLR 66, QBD(OR), at page 78 (also (1989) 5 Const LJ 73). Victoria University of Manchester v Hugh Wilson (1984) 2 Con LR 43, at page 73. Alexander Corfield v David Grant (1992) 59 BLR 102, QBD(OR), at page 119 (also 29 Con LR 58). Consarc Design Ltd v Hutch Investments Ltd (2002) 84 Con LR 36, TCC, at para 88 (also (2003) 19 Const LJ 91). 2 His conclusion was that, ‘It seems to me that inspection is a lesser responsibility than supervision.’9 It may be readily conceded that engineers do still undertake supervision,10 that architects in many jurisdictions have statutory obligations of supervision11 and that UK architects could still undertake supervision expressly or by implication.12 But it seems logical that the ‘lesser responsibility’ of inspection would afford fewer opportunities for a review of the design than a full supervision obligation. It is surely beyond question that an architect who undertook design services only and had no part in the construction phase must be regarded differently in terms of ongoing responsibility. If that is right, it would follow that different levels – and different durations – of a duty to review would attach to different packages of professional services to be supplied. In Tesco Stores v The Norman Hitchcox Partnership,13 the architect had been engaged to design shell works but was not involved in the site-based phase of the works whilst the building contract was in progress. Later he was engaged by Tesco in respect of the fitting out works of the completed development. HHJ Esyr Lewis QC said that such latter engagement could not enlarge the contractual duties under the original retainer to design the shell works. As to the latter, he had a continuing contractual obligation to answer reasonable queries about his drawings which might have arisen during the construction period and to draw attention to and, if necessary, correct any deficiency of which he became aware during that period. Precisely what it is that the architect must do as part of his obligation to review was addressed in the Technology and Construction Court in New Islington and Hackney Housing Association v Pollard Thomas and Edwards.14 In that case, Dyson J (as he then was) found that the extent of the duty would indeed depend upon what the designer had originally undertaken. The case concerned serious noise disturbance experienced by tenants in a housing association development as a result of inadequate sound insulation between flats. Since it was in dispute whether the claim against the architects was out of time, it became crucial to establish when the cause of action accrued. Dyson J began his consideration, the most detailed undertaken of the issue, by accepting the proposition that ‘a designer who also supervises or inspects work will generally be obliged to review that design up until that design has 9 10 11 12 13 14 Consarc Design, see note 8, at para 88. See for example Department of National Heritage v Steenson Varming Mulcahy (1998) 60 Con LR 33. Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong SAR, for example. For a full consideration of the duties involved in inspecting the quality of work, see McGlinn v Waltham Contractors Ltd (No 3) [2007] EWHC 149, TCC (111 Con LR 1). Tesco Stores Ltd v The Norman Hitchcox Partnership Ltd (1997) 56 Con LR 42, QBD(OR). New Islington and Hackney Housing Association Ltd v Pollard Thomas and Edwards Ltd [2001] BLR 74, TCC (also 85 Con LR 194, 17 Const LJ 55). 3 been included in the work’, and noting that, ‘In a number of cases, it has been held that this duty continues until practical completion.’15 Even at this stage Dyson J added the caveat that, ‘… it is necessary to look at the circumstances of each engagement …’16 His view of the Sachs LJ dictum in Brickfield Properties17 is enlightening: ‘But Sachs LJ was not concerned to explore the scope of an architect’s continuing duty to review his design. In my judgment, the duty does not require the architect to review any particular aspect of the design that he has already completed unless he has good reasons for so doing.’18 [emphasis added] Dyson J also took a restrictive view of Judge Bowsher’s comments in the University of Glasgow case19 stating: ‘I do not believe that Judge Bowsher was stating a general principle that an architect is usually under a duty to review his design even after practical completion. I think that his decision was heavily coloured by the special facts of the case. In my view, that case should be regarded as an example of an architect agreeing to investigate the cause of defects in a building outside the terms of his original retainer, and not as an example of the performance of a continuing duty to review his design under the original contract of engagement.’20 [emphasis added] So what are the circumstances in which the architect must review his design? The earlier cases had led the writer to conclude that some form of trigger event was necessary and it was not sufficient merely to point to the fact of the architect’s continuing involvement in the project. Thus HHJ Stabb QC in Merton v Lowe, while describing the duty of design as ‘a continuing one’, qualified this by reference to ‘… the subsequent discovery of a defect in the design, initially and justifiably thought to have been suitable’ the effect of which was that it ‘reactivated or revived the architect’s duty in relation to design and imposed upon them the duty to take such steps as where necessary to correct the results of that initially defective design.’21 [emphasis added] It is true that HHJ Newey QC in Equitable Debenture Assets Corporation had referred to an obligation to design by the architects which included ‘the duty to check their initial design as work proceeded and to correct it if necessary’22 [emphasis added]. However it should be recalled that on the facts, the sealant 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 14. He cited Equitable Debenture Assets Corporation and Victoria University of Manchester, see notes 4 and 6. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 14. Brickfield Properties, see note 2. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 20. University of Glasgow, see note 5. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 21. Merton v Lowe, see note 3, at page 133. Equitable Debenture Assets Corporation, see note 4, at page 24. 4 of the curtain walling (whose erroneous specification lay at the heart of the problem) had failed from the start, so that the ‘buildability’ difficulties experienced by the contractors had been known to the architect for many months. In other words, it should not be assumed that HHJ Newey QC was suggesting the duty to review the design arose automatically in the absence of a trigger event. More obviously consistent with Merton v Lowe23 was the qualification of HHJ Newey QC in the Victoria University of Manchester case to the effect that the architect’s duties included ‘when and if necessary, reviewing and amending the design.’24 Similarly, HH Judge Bowsher QC in the University of Glasgow case was concerned with the situation ‘… where, as here, an architect has had drawn to his attention that damage has resulted from a design which he knew or ought to have known was bad from the start ...’25 In such circumstances, the designer would have ‘a particular duty to his client to disclose what he had been under a continuing duty to reveal, namely what he knows of the design defects as possible causes of the problem.’26 The writer previously concluded that it would be wholly artificial to suggest that, absent a trigger event, the architect should be under a continuing duty to look at and review his design. This conclusion was consistent with that subsequently reached by Dyson J in New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, where he considered the practical implications with a hypothetical example of negligent foundation design: ‘But in what sense and to what extent is the architect under a duty to review his negligent design once the foundations have been designed and constructed? In my view, in the absence of an express term or express instructions, he is not under a duty specifically to review the design of the foundations unless something occurs to make it necessary, or at least prudent, for a reasonably competent architect to do so.’27 Dyson J gave examples of ‘triggers’ of the duty such as if: ‘… before completion, the inadequacy of the foundations causes the building to show signs of distress; or if the architect reads an article which shows that the materials that he has specified for the foundations are not fit for their purpose; or if he learns from some other source that the design is dangerous.’28 23 24 25 26 27 28 Merton v Lowe, see note 3. Victoria University of Manchester, see note 6, at page 73. University of Glasgow, see note 5, at page 78. University of Glasgow, see note 5, at page 78. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 15-16. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 16. 5 In such circumstances of actual knowledge, Dyson J was in ‘no doubt that the architect would be under a duty to review the design and, if necessary, issue variation instructions to the contractor to remedy the problem.’29 On the facts, Dyson J rejected the suggestion that a trigger event had actually occurred. All that had happened was that, once the problem of soundproofing had become apparent after practical completion, the employer had asked two discrete questions about the soundproofing specification which the architect had answered. Given that the architect’s engagement was over, it was not incumbent on him to do anything else, such as revisit the quality of his original design. In summary, Dyson J’s analysis resolves two questions and leaves one unresolved. First, it shows that the absence of a trigger would be fatal to the claim: ‘But in the absence of some such reasons as this [the examples set out above], I do not think that an architect who has designed and supervised the construction of foundations is thereafter under an obligation to review his design.’30 Second, it is now clear that the existence of a duty to review must depend upon some continuing involvement with the project after the design stage, at least in contract: ‘Whether he is in fact under such a duty when he has actual or constructive knowledge of his earlier breach of contract will depend on whether the contract is still being performed. If the contract has been discharged (for whatever reason), then the professional person may be under a duty in tort to advise his client of his earlier breach of contract, but it is difficult to see how he can be under any contractual duty to do so.’31 [emphasis added] This latter proposition is supported by the views of Ramsey J in Oxford Architects Partnership v Cheltenham Ladies College (discussed further below) in which he said: ‘If an architect merely carries out a design which is issued to a contractor for construction then it is difficult for a continuing duty to arise during the period of construction.’32 The point which Dyson J did not, it is submitted, resolve conclusively is whether an architect is liable for breach of duty where he is actually wholly unaware of the trigger event and therefore genuinely fails to realise that there was a design problem when reasonable skill and care would have enabled him to do so. An example might be the architect who subsequently should have become aware of an article in a journal condemning the use of certain 29 30 31 32 New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 16. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 16. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 18. Oxford Architects Partnership v Cheltenham Ladies College [2006] EWHC 3156, TCC, at para 24 (also [2007] BLR 293). 6 materials which he had specified in the past, in circumstances where the architect had no actual knowledge of the article. The nearest Dyson J came to expressing a view on this point was in holding: ‘In my judgment, the duty does not require the architect to review any particular aspect of the design that he has already completed unless he has good reason for so doing. What is a good reason must be determined objectively, and the standard is set by reference to what a reasonably competent architect would do in the circumstances.’33 The importation of the Bolam34 standard of reasonable skill and care suggests the likely answer, but the previous cases had dealt only with situations where a trigger had occurred to the architect’s knowledge, not circumstances where the architect was completely unaware of the trigger event. It may be that HHJ Humphrey LLoyd QC’s decision in Payne v Setchell took this last point closer to conclusion. The formulation of his finding was that: ‘… a designer’s continuing duty of care only requires a reconsideration of the design if the designer becomes aware or should have been aware of the need to reconsider the design’.35 [emphasis added] That said, the point does not appear to have been fully argued in that case. In Oxford Architects Partnership, Ramsey J also applied the standard of reasonable care to the duty to review, once it had been triggered: ‘In terms of a breach of contract, if an architect has good reason to review any aspect of the design then a breach will occur if the architect fails to review the design or if the architect reviews the design but fails to do so properly in accordance with the terms of engagement.’36 Whilst this relates to the standard to be applied once the duty arises, these words might also be extended to the test for determining whether the duty arises. The indications are, therefore, that a duty to review can arise even if the architect has no actual knowledge of the trigger event, although in practice he usually will. Many of the previous cases, including New Islington and Hackney Housing Association37 in particular, were concerned with trigger events which occurred after the original design had been fully implemented. In Oxford Architects Partnership, it became relevant to consider when the duty to review a design arose during the normal RIBA stages. 33 34 35 36 37 New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 20. Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 1 WLR 582, [1957] 2 All ER 118, QBD. Payne v John Setchell Ltd [2002] BLR 489, TCC, at para 21. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 27. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14. 7 In that context, Ramsey J attempted to dispel what he called ‘some confusion’ over the effect of the continuing duty to review as a cause of action. Part of this confusion lies in the ambiguous terminology of a ‘continuing duty to review a design’ when, in truth, it is no such thing: ‘If an architect produces a design which is in breach of the terms of engagement and issues it to the contractor who constructs the work to that design, then a breach of contract will occur when, for instance, the architect under Stages F to G “prepares production drawings” or under Stage J “provides production information” as required by the building contract, a cause of action will then accrue based upon that breach of contract.’38 However, the so-called ‘continuing duty’ would not ‘… give rise to a single and continually accruing cause of action. Rather, a different cause of action accrues at various stages. Thus, the cause of action for a failure properly to review the design is a different cause of action from a failure to provide a proper design in the first place. The causes of action will therefore accrue on different dates.’39 As the editors of the Building Law Reports point out in their Commentary, this may present practical difficulties in determining whether the architect is under a continuing duty to review the design up until the date of completion of the negligently designed work. ‘Once an architect has completed his design, an obligation to ‘review’ might well occur at various stages of the architect’s engagement. For example, the design may be submitted for regulatory approval, will be issued for construction and may be passed to a specialist sub-contractor to enable that specialist to prepare a more detailed design and working drawings. Whilst there may be many opportunities for reconsidering the design, the relevant question is whether the architect is under some obligation to review the design.’40 In other words, is a trigger event required to activate the duty to revisit the original design at each of these stages? Despite these difficulties in individual cases, Ramsey J’s analysis should be seen as an advance in understanding the nature of the designer’s duty to review his original design. 2. How long does the duty to review a design last? When considering the question of whether, at a given point in time, the architect still has ‘responsibility’ for the design, it is important to distinguish between duty and liability. In other words, the term ‘responsibility’ must be used with caution because it can be used synonymously with either of those terms. As a matter of practicality, the architect will wish to know the duration of his duty, ie the period during which he must be active to protect the client’s interests (and in principle those of third parties within the more limited scope 38 39 40 Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 28. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 29. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, [2007] BLR 293, at page 295. 8 of the tort of negligence). One might speak commonly of his ‘responsibilities’ continuing during this period. But, as should be apparent to a lawyer, at least, this is potentially quite different from the duration of the architect’s responsibility for review of design, in the sense of duration of liability. The early cases sought to address the issue of duration in the first sense described, but must now be seen in the light of the most recent judicial pronouncements. HHJ Bowsher’s view in University of Glasgow was that the continuing duty of design extends until the building is complete.41 HHJ Hicks QC, in Chesham Properties Ltd v Bucknall Austin Project Management Services approved ‘… what I take to be the thrust of Judge Bowsher’s views, as expressed in the University Court of Glasgow case’ and said that ‘I consider that such a duty would continue until the relevant defendant’s engagement on the project came to an end.’42 As set out above, in New Islington and Hackney Housing Association43 Dyson J observed that the designer who supervises or inspects will be advised to review his design up until that design has been included in the work, although he noted that the duty has in some cases continued until practical completion. From a lawyer’s perspective, the issue of importance is the duration of liability in respect of the duty to review. This is a matter of limitation and specifically when the cause of action occurs. In this respect, different considerations apply in contract and tort. In contract, the limitation period runs from the date of breach. As Ramsey J said in Oxford Architects Partnership, there may be several different breaches of a failure to review, each occurring on different dates.44 Dyson J was very clear about a claim in tort in the New Islington case: ‘In my judgment, the Association’s cause of action in negligence accrued at the latest at the date of practical completion.’45 His reasoning was based on what he called ‘interpretation’ by the Court of Appeal46 of the difficult decision of Pirelli General Cable Works Ltd v Oscar Faber & Partners.47 As applied to the case before him, this led to the following result: ‘In the present case, the sound insulation was inadequate from the date of handover. It was never capable of being fit for the purpose … From the outset, the building suffered from lack of adequate sound insulation, just as the building in Tozer Kemsley suffered from an inadequate heating and air-conditioning plant from the outset. In neither case is it necessary to identify a date when an occupant actually suffers from the 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 University of Glasgow, see note 5. Chesham Properties Ltd v Bucknall Austin Project Management Services Ltd 82 BLR 92, QBD(OR), at page 128E (also 53 ConLR 1). New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 41. In London Congregational Union Inc v Harriss & Harriss [1988] 1 All ER 15, CA, approving Tozer Kemsley and Millbourn Holdings Ltd v J Jarvis & Sons Ltd (1983) 1 Const LJ 79, QBD(OR). Pirelli General Cable Works Ltd v Oscar Faber & Partners [1983] 2 AC 1, HL. 9 defect. It is the building that suffers from the defect, and that is what is required to enable the owner to complete his cause of action in negligence.’48 The conclusion was that ‘the Association’s cause of action accrued when the buildings were handed over’,49 ie at practical completion. In the Building Law Reports Commentary to Oxford Architects Partnership,50 we are reminded that the first question which has to be answered is whether the loss is properly describable as physical damage or pure economic loss.51 In all tort cases, the limitation period runs from the date of damage and it is in this context that the question arises. Ramsey J reviewed the cases, including Abbott v Will Gannon & Smith,52 in which the case of Pirelli53 was stated to remain good law. On the facts, Ramsey J concluded that relevant damage in respect of the defects with which he was concerned occurred during the course of construction. He noted that although the employer does not obtain possession of the building until practical completion there is a complete cause of action when and if physical damage occurs before that date. An unusual feature of the Oxford Architects Partnership case concerned Article 5 of the RIBA Conditions of Engagement,54 which provided that: ‘No action or proceedings for any breach of this Agreement or arising out of or in connection with all or any of the Services undertaken by the Architect in or pursuant to this Agreement, shall be commenced against the Architect after the expiry of [six] years from completion of the Architect’s Services, or, where the Services are specific to building projects Stages K-L are provided by the Architect, from the date of Practical Completion of the Project.’55 It was argued that this clause permitted the College to bring a claim that was otherwise time barred provided it did so within six years of practical completion. On this point, Ramsey J’s conclusions were very clear: the clause ‘… provides a contractual time limit on the College’s ability to commence proceedings. It does not seek to prevent the Architects from relying on a statutory limitation defence, rather it is concerned with 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 41. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association, see note 14, at para 42. Oxford Architects Partnership , see note 32. The distinction will be well understood by lawyers. In basic terms, if the only loss is the cost of repairing the item which suffers from the defective design (including for these purposes any repairs to the building consequent thereupon) the loss is purely economic. If the defective design results in physical damage to person or other property, it is a physical damage case. An example would be a flood or fire causing damage to contents or neighbouring properties. Abbott v Will Gannon & Smith Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 198, CA, (also [2005] BLR 195, 103 Con LR 92). Pirelli, see note 47. RIBA Conditions of Engagement for the appointment of an Architect, CE/95. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 3. 10 providing an additional contractual limitation on the ability of the College to bring a claim.’56 Ramsey J has usefully clarified the relationship between contract and statute. Article 5 did not have the effect of allowing the client to sue up to six years after practical completion in circumstances where the claim would otherwise have been statute barred. He agreed that a limitation period could be extended by contract, which is a welcome confirmation of the principle that has always been understood, namely that parties can agree by contract whatever they want, but ‘To do that I consider clear words would be needed.’57 Equally, he noted that it is possible by contract to reduce the limitation period, and in this case Article 5 provided ‘an additional contractual limitation on the ability of the College to bring proceedings.’58 3. What are the legal consequences of breach of duty to review design in the sense of damages claimable? The writer’s original article in 1997 concluded that: ‘The damages recoverable from the architect or engineer are not those which flow from any original error in design, but from the failure to review the design. Such damages are likely to be more limited than appears at first sight.’59 If this was right, it would have serious consequences for a claimant, since the loss and damage might be held to have been caused by the original design error, potentially a time-barred claim, while the later breach of the continuing duty would not be causative of loss, although the claim in respect of it was still within the limitation period. A similar view was expressed by Jackson and Powell in their leading work on Professional Negligence which stated: ‘It is submitted that the contractual measure of damages for failure to review a design where a claim in respect of the original design obligations is Statute barred should be such as to put a claimant into the position that he would have been in if the design had been properly reviewed. Thus if the failure to review occurred after practical completion a claimant should be obliged to give credit for the (possibly substantial) costs which would have been incurred at that stage in correcting the design.’60 56 57 58 59 60 Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 16. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 19. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32, at para 21. See note 1, at page 226. Jackson and Powell on Professional Liability, 6th edition, John Powell QC and Roger Stewart QC (eds), 2007, Sweet & Maxwell, at para 9-032. 11 That paragraph was approved by HHJ Toulmin CMG QC in London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority v Halcrow Gilbert Associates.61 It therefore seems that damages following a failure to review a design are likely to be relatively small, save for cases where there is damage to other property. Conclusions This paper set out to consider three questions relating to the designer’s duty to review design. 1. What does the duty to review a design comprise? There is unlikely to be a duty without a ‘trigger’, such as knowledge of a structural problem or other reason to doubt the design’s adequacy in hindsight. Whether failure to even appreciate the existence of a problem could be sufficient is not conclusively decided. The better view is that it could, given lack of reasonable care and skill in assessment or omission to assess (Payne v Setchell62). Following the trigger, the duty is to check the initial design, correct it if possible and issue any necessary instructions to the contractor for remedial works. The standard to be met in this further work would be that of the ordinary competent practitioner. New Islington and Hackney Housing Association63 contains the most detailed consideration of this aspect. Following Oxford Architects Partnership,64 it can be stated clearly that a ‘continuing’ duty will almost never exist where the original services undertaken were limited to design. Services equating to RIBA Work Stages K-L would be required in order to found the duty. A duty to review design is separate from the original design obligation; the description of a ‘continuing’ duty may be unhelpful. Breach of the review duty is a separate cause of action, depending on what the architect has been asked to do. 2. How long does the duty to review a design last? The duty to review would not continue beyond practical completion, in the absence of special facts. After that, a trigger event would be required. The duration of liability (as opposed to duty) is governed by the limitation legislation. The Oxford Architects Partnership case confirms that the parties can vary the limitation periods upwards or downwards by agreement, although very clear express words would be necessary to permit a longer period than is provided by the statute. 61 62 63 64 London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority v Halcrow Gilbert Associates Ltd [2007] EWHC 2546, TCC, at para 98 (also (2008) 24 Const LJ 103). Payne v Setchell, see note 35. New Islington & Hackney Housing Association, see note 14. Oxford Architects Partnership, see note 32. 12 3. What are the legal consequences of breach of duty to review design in the sense of damages claimable? In most cases, where the claim is based on the cost of repair of the defectively designed item itself, quantum is likely to be small if the duty to review accrued after the construction work has been completed. That is because the cost of the work will already have been incurred: see London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority.65 The position will be different if damages are claimed not merely in respect of the building itself but also in respect of other property, for example following a flood or fire caused by a failure to review the design. Alexander Nissen QC, LLB Hons, FCIArb is a member of Keating Chambers, London; he is also a contributing editor to Keating on Construction Contracts and one of the commentators for the Construction Law Reports. © Alexander Nissen and the Society of Construction Law 2008. The views expressed by the author in this paper are his alone, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Society of Construction Law or the editors. Neither the author, the Society, nor the editors can accept any liability in respect of any use to which this paper or any information or views expressed in it may be put, whether arising through negligence or otherwise. 65 London Fire and Emergency Planning Authority, see note 61. 13 ‘The object of the Society is to promote the study and understanding of construction law amongst all those involved in the construction industry’ MEMBERSHIP/ADMINISTRATION ENQUIRIES Jackie Morris 67 Newbury Street Wantage, Oxon OX12 8DJ Tel: 01235 770606 Fax: 01235 770580 E-mail: admin@scl.org.uk Website: www.scl.org.uk 14

![(NPD-60) []](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007320126_1-47edb89d349f9ff8a65b0041b44e01a8-300x300.png)