1932 - 1938: Wassily Leontief´s Early Papers

advertisement

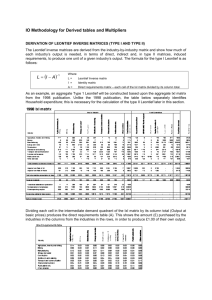

1932 - 1938: Wassily Leontief´s Early Papers. Besides the Input-Output Model. Fidel Aroche1 First Draft. Please do not quote Abstract: W. Leontief moved to the U.S. in the early 1930’s with an offer to work at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and would later accept a position in Harvard University, where he would develop his 1936 and 1937 papers presenting the Input-Output model. At arrival at the U.S. however, Leontief would publish a (large) number of papers dealing with various other issues, mainly methodological and also theoretical. These articles are interesting and useful for understanding the theoretical background and Leontief’s preoccupations had at the time, which would also influence the development of the IO model. This paper analyses a few of such early papers, which appeared in journals nowadays included in JSTOR, searching for possible connections and extension to the main creation of Leontief’s. Fidel Aroche, e-mail: aroche@servidor.unam.mx, Postgrado, Facultad de Economía, UNAM, Av. Universidad 3000, Ciudad Universitaria, 04510 México, D. F. MEXICO. I am thankful to Adrián Hurtado for his assistance in the elaboration of this paper. 1 1 1932 - 1938: Wassily Leontief´s Early Papers. Besides the InputOutput Model. In 1936 W. Leontief published an article, “Quantitative Input and Output Relations in the Economic System of the United States” and in 1937 he published “Interrelation of Prices, Output, Savings and Investment” both in the Review of Economics and Statistics (Vol. 18 pp. 105-125 and Vol. 19 pp. 109-132 respectively), while being a professor at Harvard University. These papers present what would become the Input-Output (IO) model, which would also be later completed and extended. Besides these fundamental pieces, though W. Leontief published also a number of articles along the 1930’s both in German and in English which were not directly related to the IO model, but reveal the academic discussions in which Leontief was involved at the time, as well as his interests on other aspects of the profession. Investigating these issues might be useful to understand the theoretical interests Leontief held at the time he developed his IO model, which could also allow a more thorough discussion on the grounds the model was developed. This paper overviews those articles by W. Leontief that appeared during the decade of the 1930’s in English, stressing also the authors with whom Leontief maintains discussions and the main ideas about. 1. - The published papers Between 1932 and 1938 Leontief published the following papers in English in nowadays journals included in JSTOR, chronologically organised: 1. A comment to the book Der Sinn des Monopols in der gegenwärtigen Wirschaftsordnung by Erich Egner. Berlin: Paul Parey (1931). Published in The Journal of Political Economy Vol. 40, No. 5 (October, 1932) pp. 714-716. 2 2. “The Use of Indifference Curves in the Analysis of Foreign Trade”, published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 47, No. 3 (May, 1933) pp. 493503. 3. “Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: A Reply” published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol . 48, No. 2 (February, 1934) pp. 355-361. 4. “More Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: A Final Word” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 2 (August, 1934) pp. 755-759. 5. “Interest on Capital and Distribution: A Problem in the Theory of Marginal Productivity” published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol . 48, No. 2 (November, 1934) pp. 147-161. 6. “Price-Quantity Variations in Business Cycles” published in the Review of Economics and Statistics Vol. 17, No. 4 (May, 1935) pp. 21-27. 7. “Composite Commodities and the Problem of Index Numbers” published in Econometrica Vol. 4 No. 1 (January, 1936) pp. 39-59. 8. “Stackelberg on Monopolistic Competition” published in The Journal of Political Economy Vol. 44, No. 4 (August, 1936) pp. 554-559. 9. “The Fundamental Assumption of Mr. Keynes’ Monetary Theory of Unemployment” published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol . 51, No. 1 (November, 1936) pp.192-197. 10. “Implicit Theorizing: A Methodological Criticism of the Neo-Cambridge School” published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol . 51, No. 2 (February, 1937) pp. 337-351. 11. “The Significance of Marxian Economics for Present-Day Economic Theory” published in the American Economic Review Vol. 28, No. 1 Supplement, Papers and Proceedings of the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (March, 1938). 3 Out of these eleven papers, in the first one, of 1932 Leontief signs as a member of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER); from the second paper (of 1933) onwards he signs from Harvard University, although in the fifth paper, “Price-Quantity Variations in Business Cycles”, Leontief mentions the NBER as the place he started a research project conducting to this result. Papers number 1 and 7 are comments to books published in Germany and both refer to the analysis of non competitive market structures. In the 1932 publication Leontief makes a methodological analysis and underlines that German economics were at the time opening new fields to the theory, while recovering some features of the older economists, like Quesnay, seeking for the final causes and meanings –a theolological vision- supported by a philosophy derived from Husserl and Heidegger and following the methodological principles of earlier German economists as Rodbertus and von Stein, an attitude that Leontief recognises to be quite extended among German economists. So the author of the book in question, Erich Egner, explains the rationality of monopolies in the “modern” capitalistic economy, not only its behaviour as it had been dealt with to that date –presumably in the Anglo Saxon literature. The rôle of a monopoly would be close to that of an entrepreneur in Schumpeter’s theory of economic dynamics for which monopolies are seen as beneficial for the strength of the national economy. The comment on von Sackelber’s book Marktform und Gleichgewicht (Market Structure and Equilibrium), published in Vienna in 1934 by J. Springer, appeared in 1936, when no English translation of the book was available; later on von Stackelberg’s oligopoly models would become standard in text books on microeconomics. In this comment Leontief also makes a thorough comment on the methodology von Stackelberg employed in the book, devoted to explain the theory of oligopolistic competition (called by Leontief “monopolistic”), including a critical survey on the developments by other authors, from Cournot to their contemporaries, J. Robinson and E. Chamberlin2. This is a text developed on strong analytical foundations, although as many books of the time, do not present any mathematical formulation in the main text, reserving those to appendices. Robinson J. The Economics of Imperfect Competition. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1933 and Chamberlin E. Theory of Monopolistic Competition. Cambridge(Mass.): Harvard U.P., 1933. 2 4 Paper No. 3 “Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: A Reply” is in fact a part of a controversy Leontief held with Ragnar Frisch on the statistical evidence and analysis of supply and demand functions; this paper followed a booklet by Frisch "Pitfalls in the Statistical Construction of Demand and Supply Curves" (1933) in Veröffentlichungen der Frankfurter Gesellschaft fur Konjukturforschung , edited by Eugen Altschul, Neue Folge Heft 5, Leipzig, Hans Buske (39 pp.) where the latter criticizes a paper by Leontief (Ein Versuch zur statischen Analyse von Angebot und Nachfrage or An Attempt for a Statistical Analysis of Supply and Demand, in Welwirtschaftliches Archiv Vol. 30, No. 1, 1929) that presents a method developed together with R. Schmidt to derive supply and demand curves from empirical data on price and quantity variations. This paper received a long comment by Elizabeth W. Giloboy (1931). The reply by Leontief is tidy and thorough, analyzing every bit of Frisch’s argument to conclude that Frisch’s work deserves his own observation to Leontief’s. The controversy however would continue in Ragnar Frisch’s reply “More Pitfalls in Demand and Supply Curve Analysis” that appeared in The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol . 48, No. 4 (August, 1934), pp. 749-755. Where Frisch states that Leontief is one example of the fact that the empirical analysis on the demand and supply analysis is a field where mistakes and confusion thrives. Frisch claims that data contradicts Leontief’s assumptions and method of analysis of the phenomena in question; namely, that the shifts of the supply and demand curves are independent, whereas in fact there was quite a lot of research on the correlation of those. Assuming the inexistence of a fact (as Leontief seems to have done) is not enough to validate a hypothesis. Later on, Frisch goes through the implication of some of the conclusions Leontief reaches in the earlier paper. Finally, Frisch concludes, Leontief’s paper did not bring any further valid result, besides that his analysis is mistaken and fails to prove that Frisch’s work is incorrect (p. 755). Leontief replies in the paper “More Pitfalls in Demand and Supply Curve Analysis: A Final Word” in the same issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol . 48, No. 4 (August, 1934), pp. 755-759; he begins to examine the theoretical implications of the interdependence of the shifts of the supply and demand curves: the cases of 5 pure demand or supply shifts would be impossible (p. 756). Moreover, Leontief charges, Frisch fails to single out cases where empirical data contradicts his hypothesis. Jacob Marschak -at that time at the Universisty of Oxford- intervenes in the discussion with “More Pitfalls in Demand and Supply Curve Analysis: Some Comments” in the same issue of The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol . 48, No. 4 (August, 1934), pp. 759-766. Here Prof. Marschak begins by explaining the theoretical environment in which this discussion took place. First of all the statistical research on price theory was not as meticulous as the theoretical one, then theoretical researchers had to adjust the data in order to isolate the different sources of variations in the shape of the curves. Leontief attempted to derive method to eliminate time-shifts assuming they are of random nature. Frisch introduced notions to Leontief’s method which enabled him to develop E. Working’s statements (1927) and simplify the latter method. Marschak continues explaining Leontief’s method using Frisch’s terminology, finding the points of controversy and the theoretical grounds of the discussion and although Marschak acknowledges Leontief’s method value, but points out that the conclusions and implications derived from the analysis are mistaken. 2. - Papers on applied research. In 1933 Leontief published “The Use of Indifference Curves in the Analysis of Foreign Trade” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (Vol. 47 No. 3 pp. 493-503). This article suggests ways to study international trade using indifference curves as theoretical tools as “… had been used by Marshall, Edgeworth or Pareto” (p. 493). The suggestion is advance theoretical discussion making use of such devices, instead of numerical examples, which would be more cumbersome. Leontief considers diagrams useful tools to disclose the relationships between national and international equilibrium and shows how trade between two countries exchanging two commodities can be plotted in a two-dimensional diagram and how equilibrium is attained under different circumstances, including changing relative prices and the terms of trade. The paper is written in a language and style that 6 assumes the reader is familiar with indifference diagrams in the neoclassical consumer theory, as well as with the neoclassical theory of international trade, so much that there is no explanation of either. Knowledge of the former also assumes familiarity with the theory of utility and demand in order to follow the argument, it is also required that the reader has more than an elementary grasp on the neoclassical production theory, which is assimilated to the indifference graph. In the end of the article our author suggests ways to include in the analysis further commodities and countries, capital movements and transfer problems and even monetary aspects of international trade. All those extensions would be feasible using indifference curves, changing or extending the dimensions of the diagrams. Professor Leontief of Harvard University published the article “Price-Quantity Variations in Business Cycles” in The Review of Economics and Statistics Vol. 17, No. 4, May, 1935, pp. 21-27. As we learn in the publication itself, this is a result of a long research which he had started at the NBER and continued at Harvard University under a grant by the Harvard University Committee on Research in the Social Sciences to continue that project. The paper deals with the construction of supply and demand curves using statistical data, in connection to the study of price and quantity variations. Apparently at that time empirical and statistical price analysis was concerned with finding the shapes of those functions, which seemed to work according to the theory for agricultural commodities, but that was not so when applied to industrial products. Leontief cites Professor Henry Ludwell Moore (but no exact quotation appears in the text) who wrote among other books Economic Cycles: Their Law and Cause, New York: The Macmillan Company (1914) and Forecasting the Yield & the Price of Cotton, New York: The MacMillan Company (1917). Professor Moore had been a student of Menger and Walras in Europe and attempted an empirical examination of the marginalist propositions, particularly he tried to derive statistically demand curves, as well as investigating the connections between business cycles and equilibrium theory and in his 1929 Synthetic Economics (1929), Moore attempted to estimate Walras’ general equilibrium system (http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/moore.htm). Professor Moore concluded 7 that both general prices cycles (by virtue of agricultural supply) and the business cycles were driven by rainfall cycles (Moore, 1914: p. 124). Leontief acknowledges that in spite of theoretical expectations (from a partial equilibrium viewpoint) that supply and demand are independent, all parts of the economic system are interrelated3, as any theory on the business cycle would state and thus as stated in footnote 3 (p. 21) any attempt to approach the analysis of a particular market from a partial equilibrium perspective is doomed to failure. Nevertheless the complexities of the general equilibrium model are such that it would not be possible to fill the Walrasian supply and demand functions with statistical data. Yet Leontief analyses the behaviour of price and quantity of cotton and pig iron in the United States for a period raging from 1880 to 1923 and 1926 (for different variables) and comes to the conclusion that the price quantity patterns of pig iron are connected with long “trend cycles”, while the cotton-textile production had been independent of the general economic development trends, for which the structural position of this industry changed. Interestingly, one of the few authors that Leontief mentions and quotes extensively is Arthur Burns, from whose book Production Trends in the United States since 1870 (National Bureau of Economic Research, New York, 1934) Leontief acknowledges taking some data to carry on his analysis on the pig iron behaviour. Burns is one of the academics in the US studying the business cycle at that time and would later take public office (http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/burns.htm). The third paper Leontief published in English between 1932 and 1938 dealing with methodological criticism is “Composite Commodities and the Problem of Index Numbers” in Econometrica Vol. 4 No. 1 (January, 1936) pp. 39-59. Here again Leontief expresses his interest in the development of quantitative analysis in economics, as well as his interest to study supply and demand functions. Besides the problem of index numbers, this article deals mainly with the treatment of composite commodities, which pose practical problems when they are According to Marschak (1934), this is an assumption Leontief advances in the controversy with R. Frisch on the construction of supply and demand curves. 3 8 encountered in empirical work and the construction of statistical databases, for instance, those concerned with measuring quantities, prices and utility, among others. Leontief begs the attention of the economists to these problems, which are normally left to the statistician. Apparently at the time there was a vivid discussion about index numbers and also at the NBER, the institution that housed Leontief at arrival in the U.S., which was founded by Wesley C. Mitchell, an influential researcher on the index number issues, as well as on the business cycle. The study of price indices was therefore a prominent part of the measurement activities of the Bureau (Benzhaf, 2004). Besides, index number contributions can also be found in contemporary European publications as well; for example, John M. Keynes includes a survey on the discussion on index numbers in Chapter VIII of his A Treatise of Money. A Pure Theory of Money, first published in 1930; also G. Harbeler produced in 1927 his Der Sinn der Index-Zahlen, Tübingen (The Meaning of the Index-Number) and in 1935 “Composite Commodities and the Problem of Index Numbers” by Hans Staehle appeared in the Review of Economic Studies (Vol. 2 No. 3, June, pp. 163-188). This author published the book The International Comparison of Food Costs. A study of Certain Problems Connected with the Making of Index Numbers (International Labour Office Studies and Reports, Series N, No. 20, 1934), as well. Arthur Bowly, the professor of the London School of Economics commented this publication in 1935 in The Economic Journal Vol. 45. Leontief claims to have completed his paper earlier and communicated to Schumpeter’s Discussion Group at Harvard University in the autumn of 1933; in 1935 it was presented at the meeting of the Econometric Society. Nevertheless in the same footnote Leontief recognises that his paper is similar to that by H. Saehle, (up to sharing the title). It is known that the latter was interested in the comparison of standards of living between different social groups within one country or between similar groups in different countries, as well as the relative purchasing power of different currencies, among other subjects (Carré, 1961). The index number discussion is related to the problem of maintaining the utility fixed for a given individual (or individuals with identical tastes) under different price regimes. Thus the index number can be written as a ratio of two expenditure 9 functions with identical utility level (u*) and different price levels (p1, p2): E1(p1, u*)/E2(p2, u*). This approach is attributed to Alexander Alexandrovich Konüs (Banzhaf, 2004), who worked at the Institute of Conjuncture in Moscow, founded by Nikolai Kondratief as a center for the study of business cycles in 1923, where also E. Slustky worked for a while as well (Diewert, 1993). One of the problems approached by the latter is also the effects on demand when prices change (Mas Colell, Whinston and Green, 1993), although Slutsky’s problem is more complex, since it might be about a change in relative prices, which also imply a change in income and the index number problem is only concerned with changes in the general price system. One of the assumptions in the theory is that demand is homogeneous in prices: if they change, demand remains intact. In the first sections of article Leontief remains close to Keynes’ survey on the index number discussion (Keynes 1930) and later discusses the two formulas that Keynes picks as “… theoretical and practically eligible for use in the measurement of composite prices…” (p. 46); later on proceeds to analyse them critically, finding their weaknesses and possible applications, as well as connections with other theoretical and empirical discussions. Perhaps the interesting element in respect to the purpose of this paper is noting the familiarity that Leontief shows to have with the discussion and the thoroughness displayed to analyse the issues that concern the piece of work. Another piece of critical survey on other economists work is that developed in “Implicit Theorizing: A Methodological Criticism of the Neo-Cambridge School”, published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 51 No. 2 (February, 1937) pp. 337-351. This is an interesting critical work against the theorizing method of the Cambridge School of Economics, although Lionel Robbins from the University of London is also mentioned as a practitioner of those methods that deserve such an article of analysis4. First of all, Leontief states that a comparison between the NeoLionel Robbins published An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. Macmillan and Company Limited. London, in 1932. 4 10 Cambridge and the orthodox theory should be made on methodological grounds, rather than on the discussion concerning theoretical issues, such as the equality between savings and investment or the significance of the multiplier (p. 337). In the end both schools of thought would agree on the phenomena to be studied: economic reality of common experience, as well as on the point of departure and the goals of analysis. Differences would lie on the intermediate path. The correct research procedure should reduce the chances of inconsistency and logical mistakes to the minimum. It is not, then a matter of picking “the correct” evidence or the truth content of any theoretical statement, but rather the problem is that of picking the right method of proof. The logical pattern of theoretical analysis used by Cambridge economists is liable to increase the danger of theoretical errors and fallacies (p. 339). Apparently Leontief locates the most salient characteristic of the Cambridge method of analysis on a peculiar use of definitions (p. 339). Leontief postulates the importance of an axiomatic construction of the theory, deducting theorems from basic postulates and definitions and warns against the introduction of new concepts and definitions at intermediate stages of that construction process, unless the analyst is skilful enough as to avoid formal inconsistencies and logical mistakes. Often implicit definitions are introduced as well as implicit theorems containing implicitly defined terms which are taken as solutions to the originally posed problem, which is of course a mistake leading to false conclusions. Apparently however, this is a common mistake, according to Leontief and the practitioners that use implicit solutions seldom offer explicit interpretations of those short-cut solutions. On the contrary, Leontief states, within the orthodox theory framework all definitions are explicit and unsolved problems cannot be hided (p. 344). It is thus possible to study how theory advances from its basic foundations. The implicit theories, however often offer propositions that have no relations whatsoever with their theoretical bases. 11 As an example of that short-cut reasoning Leontief proposes the concept of “Corrected Units”, by Joan Robinson, in her Economics of Imperfect Competition (1933) p. 332, which herself corrected in her article “Euler’s Theorem and the Problem of Distribution” (1934). Another example of those implicit solutions is Keynes’ (1936) definition of “labour units” and “wage units”, as well as “aggregate demand” and “aggregate supply” in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Richard Kahn defines also the “ideal output” in “Some Notes on Ideal Output” (The Economic Journal Vol. 45 No. 177 pp. 1-35) assuming implicitly that individuals show identical marginal utility for money and then proceeding with his argument in such a way that the whole concept of “ideal output” is in Leontief’s eyes, indefensible. Hicks proposed the concept of “elasticity of substitution” in his Theory of Wages, London: Macmillan, 1932, which caused a vivid controversy (Machlup, 1935) about which Leontief refers the existence of over twenty published comments and papers by eleven authors (both orthodox and from Cambridge) and the puzzlement of the author before the proposed concept (Hicks, 1936)5. Hicks’, being a neoclassical economist, is nevertheless a practitioner of the (English?) short-cut method of analysis and when explaining himself in the latter paper, he continues to introduce new implicit definitions. At the end of the article Leontief attempts to make it clear that even if he chose examples of this malpractice mainly from Cambridge economists, the error is not exclusive of them, there is even the Austrian concept of “period of production” and the Marxist one of “socially necessary labour”. These however, are occasional lapses, rather than a major analytical weapon that has become in the hands of “... a now conspicuous group of theorists ...” (p. 351). Theoretical discussions Hicks R.(1936) Distribution and Economic Progress in Review of Economic Studies Vol. 4 No. 1 October 1936 pp. 5 12 The article “Interest on Capital and Distribution: A Problem in the Theory of Marginal Productivity” appeared in the Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 49, No. 1 (November, 1934) pp. 147-161; it aims at discussing the theory of marginal productivity in relation to the rate of interest and distribution. The paper also criticises the book Theory of Wages by Paul H. Douglas (1934), the co-author of the well known Cobb-Douglas production function. Indeed, together with H. L. Moore (see above), among others, Douglas worked on the statistical estimation of various concepts of the neoclassical theory, in particular the marginal productivity theory, out of which he would formulate the commented book (http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/profiles/douglas.htm, Clark, 2008). Leontief presents a meticulous discussion on the neoclassical theory of production in a competitive environment and then concludes that on the one hand capital and labour are factors of production, which can be measured in physical terms and on the other, if “interest” and “wages”6 are their prices, these variables should equal the factorial marginal productivity, as Douglas and the theory conclude. It is not easy though to measure these production factors, as they are not homogeneous7. Then, Leontief wonders about what capital is and, as later on many other theorists have concluded, Leontief states that this is not a precise concept, as it includes first of all fixed capital and in a wider concept, at which Douglas dwells: capital should include intermediate inputs as well, but then, why would it not include the wage fund, whence labour should naturally be paid “wages”, while, the wage fund, as a part of capital, should earn interest (p. 149). Such remuneration is not included in either Douglas’ nor Clark’s production functions -Leontief notices. The production function determines labour productivity and either that equals wages or wagefund interest, but not both. Further, if the marginal productivity of capital determines interest, the price of machinery remains unexplained, because the wage-fund has been excluded from capital. Thus the whole theory of interest is not acceptable and more, Douglas’ position is not clear in this respect. Leontief however offers a solution that “... emerges from the writings of Jevons, Bohm-Bawerk, Wicksel and their successors... the problem in hand can be Quotation marks in the original The controversies on the nature of capital have been extensive and have had various origins (see Robinson J., 1953; Sraffa, 1926, Monza, 19) 6 7 13 narrowed down to the question: how does a firm adjust itself to a given rate of interest?” (p. 150). Leontief suggest to approach the issue from the perspective of production, which is a transforming process that takes time and where labour, raw materials and machinery enter in a constant stream. Time must be taken into account in the production function and the entrepreneur must advance lump sums before starting production. Then Leontief agrees with Frank W. Taussig, who attempted to include the theory of the wages fund within mainstream economics, and who also proposed that the relative prices of production factors are equal to their discounted marginal productivities. Moreover, the interest rate is proportional to the marginal time productivities of the factors “discounted” by the values of the current expenditures for each factor. Nevertheless, if production time is constant, the marginal productivity of the turnover periods of each factor becomes senseless and, for two factors, there will be at least three unknowns: the price for each factor and the interest rate. Then a distinction between the prices and the interest rate is not possible, unless a capital supply function was obtainable. In Douglas’ theory, however, it would seem the turnover of the wage fund is infinitely fast and thus its interest rate is null or, alternatively, as time factors are constant, time derivatives become zero. In any case, according to this author, time does not influence production, and does not accept the existence of a wages fund. Thus, Leontief reminds the reader, Douglas differs from Jevons, Bohm-Bawerk, Wicksell and also from Marx and Mill. More important, Leontief concludes Douglas’ theory is unrealistic, even if he claims to derive it from statistical evidence. In November 1936 Leontief published “The Fundamental Assumption of Mr Keynes’ Monetary Theory of Unemployment” in the Quarterly Journal of Economics (Vol. 51 No. 1 pp. 192-197), commenting on Keynes’ The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, that appeared in February. This paper’s purpose is to examine a few basic assumptions that make Keynes’ theory divergent with that referred to by Leontief as the “orthodox classical” scheme”, which incidentally seems to know quite deeply. The main difference between those, we read in the first paragraph, resides in the shape of the labour supply, which by all means, 14 involves a more general theoretical discussion. Leontief proceeds to examine the meaning of the discussion posed by Keynes to conclude that there are a number of open questions unanswered in the General Theory (pp. 196 and 197). Leontief reminds the reader about the orthodox assumption that the system is homogeneous of degree zero in prices, that is, if all prices (the price vector) are multiplied by some number (scalar), every real individual supply and demand for any commodity remains unchanged. According to Leontief, Keynes does not seem to accept this assumption, together with that of instantaneous and frictionless adjustment process of the economic system when any monetary phenomena happens; while the latter appears to be reasonable to Leontief and is not really accepted by orthodox theorists, the former assumptions has further consequences in Keynes’ analysis, because money is no longer a neutral factor and its quantity becomes an argument in every supply and demand function. In short, if money supply fails to be that of equilibrium, unemployment and disequilibrium appear in other markets. Thus Keynes postulates a monetary theory of unemployment as a result of the non-homogeneity condition. Leontief clearly stands from the quantitative monetary theory and therefore is at odds with the conclusions of The General Theory; the disagreement goes further, though. Leontief let the reader learn that he considers Keynes’ analysis on the labour supply as unsatisfactory as is his method of analysis and that of attack the orthodox theory: “… The most effective way of disputing their (orthodox) theory would be that of discrediting these initial assumptions. Mr Keynes has not resorted to this method of attack but has attempted to show directly that the contested postulate (the homogeneity condition) itself is at variance with facts… The nonhomogeneity of the labor (sic) supply function would be proven if, under these conditions and in absence of friction and time lags, the amount of labor (sic) employed would change (…) with the variation of the price level … No demonstration of this kind is given in the pages of the General Theory of Unemployment … Mr Keynes’ assault upon the fundamental assumption of the “orthodox” economic theory seems to have missed the target.” (p. 196). The attack 15 against the novel book continues for another page and concludes in page 197 that “… it appears that Mr. Keynes’ case has yet to be proven.” The final article by Leontief surveyed in this paper is “The Significance of Marxian Economics for Present-Day Economic Theory” included in The American Economic Review Vol. 28 No. 1, Supplement, Papers and Proceedings of the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association pp. 1-9 in March 1938. This is a somewhat surprising publication since most of the previous ones published in the 1930’s by W. Leontief relate to the neoclassical school of thought, even if they might be critical of some positions. In any case, our author in the paper in question shows a thorough understanding of the works by Marx and values them as a source of methodological learning, although, once again, our author is rather critical towards Marx from a rather neoclassical position. The paper begins with Marx’s charge of fetishism to the “vulgar” or neoclassical economists in respect to the orthodox theory of prices. This theory, however, Leontief argues, is in accordance with the agents’ (consumers and producers) perception of the price and markets mechanisms “... He (the theorists) explains their (agents’) actions in terms of their own beliefs and fetishes.” (p. 2) Nevertheless, Leontief reminds that there are other issues in the (neoclassical) theory that explain phenomena assuming the ignorance of the individuals involved. However the important question concerns the meaning of fetishism. That question however is left open in the paper, but it is suggested that Marx’s objections to include conscious reactions of individual entrepreneurs and households to explain prices should be taken as erroneous. Leontief would nevertheless rescue Marx’s theory of crisis and his explanation of the business cycles. This is based on the theory of underinvestment and the law of falling rate of profits on the one hand and on the theory of underconsumption, on the other. Yet Leontief praises the Marxian schemes of capital reproduction as the keystone of the relevance of this author for the “modern” theory. 16 Leontief fails to quote, but seems to recall Löewe’s explanation of the cycle (Löewe, 1926) as well as the contributions of the Kiel school that have been characterised as “structural theories of growth and the business cycle”, according to which the relationships between economic sectors and their changes give rise to growth and cycles (http: cepa.newschool.edu/het/school/kiel.htm). Leontief argues that the complexity and the non linearity of the economic system make it impossible to decompose any commodity into its constituent parts along a time succession of stages as suggested by Bohm-Bawerk. According to Leontief, perhaps the most salient feature of Marx’s theory however, is its ability to analyse the capitalist economy and predict its future. Together with Lange (1935), Leontief reminds the reader that such ability stems from the methodology employed, which includes the use of raw data and observation of facts. That comprises the institutional or historical environment in which phenomena happen, as well as the interrelations between theoretical propositions. As opposed to “modern economic theory”, which is often a derivative from other author’s propositions and theories, Marxian theory in the hands of its originator is about theorizing form direct observation of facts and characters. It is then most informative about capitalism than other approaches. In a word, the strength of the Marxian economics lies thus in its realistic empirical knowledge of the capitalist system. Nevertheless Leontief is not ready to adopt it as the guiding theoretical framework. References Allen R. G. D., (1950) “The Work of Eugen Slutsky” Econometrica, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 209-216. Banzhaf H. Spencer (2004) “The Form and Function of Price Indexes: A Historical Accounting” History of Political Economy Vol. 36 pp. 589-616. Bowley A. L. (1935) “International Comparisons of Cost of Living”, The Economic Journal Vol. 45, No. 178 (June) pp. 301-303. Burns Arthur (1934) Production Trends in the United States since 1870 New York: National Bureau of Economic Research. 17 Carré Philippe, (1961) “Brief Note on the Life and Work of Hans Staehle” Econometrica Vol. 29 No. 4 pp. 801-810. Chamberlin E. (1933) Theory of Monopolistic Competition. Cambridge (Mass.): Harvard U.P. Cox Edwin B. (1962) “Henry Moore and the Statistical Complement of Pure Economics” American Statistitian Vol. pp. 10-13. Diewert W. E., (1993), “Konüs, Alexander Aalexandrovich” in W. E. Diewert and A. O. Nakamura (Editors) Essays in index numbers theory Vol. I. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers. Douglas P. H., (1934) Theory of Wages New York: The Macmillan Company. Flatau Paul (2002) “Hicks’s the Theory of Wages: Its Place in the History of Neoclassical Distribution Theory” History of Economics Review Jun 22, pp. 44-65. Frisch Ragnar, (1933) Veröffentlichungen der Frankfurter Gesellschaft fur Konjukturforschung Eugen Altschul Neue Folge Heft 5. Leipzig. Frisch Ragnar (1934) “More Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 4 (August) pp. 749-755 Giloboy W. Elizabeth (1931) “The Leontief and Schultz Method od Deriving “Demand“ Curves“ The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 45 No. 2 (February) pp. 218-261. Harbeler G., (1927) Der Sinn der Index-Zahlen Tübingen. Hicks J. R. (1932) Theory of Wages. London: Macmillan. Kahn R. F., (1935) “Some Notes on Ideal Output”, The Economic Journal Vol. 45 No. 177 pp. 1-35. Keynes J. Maynard, (1930) A Treatise of Money. A Pure Theory of Money. Tratado del dinero: teoría pura y aplicada del dinero. España: Aosta, c1996. Keynes J. Maynard (1936) The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. Lange O. (1935) “Marxian Economics and Modern Economic Theory.” The Review of Economic Studies Vol. 2 No. 3 pp.189-201. Lerner A. P. (1935) “A Note on the Theory of Price Index Numbers” The Review of Economic Studies Vol. 3 No. 1, pp.50-56. Leontief W. (1929) “An Attempt for a Statistical Analysis of Supply and Demand” Welwirtschaftliches Archiv Vol. 30, No. 1, 1929. Leontief W. (1932) “Egner Erich, (1931) “Der Sinn des Monopols in der gegenwärtigen Wirschaftsordnung“ The Journal of Political Economy Vol. 40, No. 5 (October) pp. 714-716. Leontief W. (1936) “Quantitative Input and Output Relations in the Economic System of the United States” Review of Economics and Statistics Vol. 18 pp. 105-125. Leontief W. (1936) “Interrelation of Prices, Output, Savings and Investment” Review of Economics and Statistics Vol. 19 pp. 109-132. 18 Leontief W., (1933) “The Use of Indifference Curves in the Analysis of Foreign Trade” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 47 No. 3 (May) pp. 493503. Leontief W., (1934a) “Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: A Reply” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 2 (February) pp. 355-361. Leontief W., (1934b) “More Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: A Final Word” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 2 (August) pp. 755-759. Leontief W. (1934c) “Interest on Capital and Distribution: A Problem in the Theory of Marginal Productivity”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 2 (November) pp. 147-161. Leontief W. (1935) “Price-Quantity Variations in Business Cycles” Review of Economics and Statistics Vol. 17 No. 4 (May) pp. 21-27. Leontief W. (1936a) “Composite Commodities and the Problem of Index Numbers” Econometrica Vol. 4 No. 1 (January) pp. 39-59. Leontief W., (1936b), “Stackelberg on Monopolistic Competition” The Journal of Political Economy Vol. 44 No. 4 (August) pp. 554-559. Leontief W. (1936c) “The Fundamental Assumption of Mr. Keynes’ Monetary Theory of Unemployment” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 51 No. 1 (November) pp.192-197. Leontief W. (1937a) “Implicit Theorizing: A Methodological Criticism of the Neo-Cambridge School” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 51 No. 2 (February), pp. 337-351. Leontief W. (1938) “The Significance of Marxian Economics for Present-Day Economic Theory” American Economic Review Vol. 28, No. 1 Supplement, Papers and Proceedings of the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (March), pp. 1-9. Löwe A. (1926) „Wie ist Konjunkturtheorie überhaupt möglich?“ Welwirtschaftliches Archiv Vol. 24, pp. 165-197. Machlup Fritz, (1935) “The Commonsense of the Elasticity of Substitution” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 2, No. 3. pp. 202-213. Marschak Jacob (1934) “More Pitfalls in the Construction of Demand and Supply Curves: Some Comments” The Quarterly Journal of Economics Vol. 48, No. 4 (August) pp. 759-766. Mas-Colell A., Whinston M. and Green J. (1995) Microeconomic Theory, New York: Oxford University Press. Moore Henry Ludwell, (1914) Economic Cycles: Their Law and Cause New York: The Macmillan Company. Moore Henry Ludwell, (1917) Forecasting the Yield & the Price of Cotton New York: The Macmillan Company. 19 Monza Alfredo (1972) Nota introductoria a la reciente controversia en la teoría del capital” El Trimestre Económico Vol. XXXIX No. 155 (July-September) pp. 545-556. Robbins Lionel (1932) An Essay on the Nature & Significance of Economic Science London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. Robinson J. (1933) The Economics of Imperfect Competition. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. Robinson J. (1934) “Euler´s Theorem and the Problem of Distribution”, The Economic Journal Vol. 44 No. 175 pp. 398-414. Robinson J. (1953-1954) “The Production Function and the Theory of Capital”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 81-106. Staehle Hans, (1935) “Composite Commodities and the Problem of Index Numbers” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 2 No. 3, June, pp. 163-188. Staehle Hans (1934) The International Comparison of Food Costs. A study of Certain Problems Connected with the Making of Index Numbers, International Labour Office Studies and Reports, Series N, No. 20. Staehle Hans, (1935) “A Development of the Economic Theory of Price Index Numbers” The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 2 No.3, pp163-188. Working Elmer (1927) “What do Statistical Demand Curves Show?” Quarterly Journal of Economics 20