History - Higher - Blast and Counterblast

advertisement

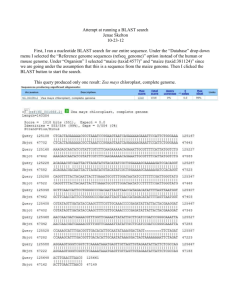

BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST I.B. Cowan, Blast and Counterblast: Contemporary Writings on the Scottish Reformation (The Saltire Society, 1960) Student Guide Issue 1: The Reformation of 1560 The nature of the Church in Scotland; attempts at reform; the gr owth of Protestantism; the Reformation of 1560 The Pre-Reformation Church These sources describe the decline of the pre -Reformation Church, morally and spiritually, in the words of authors who were staunch supporters of the Catholic Church. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 1–3 The Policy of Reform From Within Strenuous efforts were made to reform the Church in Scotland from within. Three provincial councils were held in the decade before the Reformation at which efforts were made to correct abuses. Archbishop Hamilton’s ‘Catechism’ (1552) and a ‘Godlie Exhortation’ on the Eucharist (1559), also known as the ‘Twapenny Faith’, also indicate the desire of certain sections of the clergy not only to set their house in order, but also to effect a moderation in doctrine. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 4–7 The Growth of Protestantism Efforts at reform from within the Church were largely ineffective. The Church’s financial structure meant that too little income reached or remained in the parishes. At the same time, the poverty of parish priests made the ideal of an educated priesthood no more than a pious hope. When coupled with a genuine growth in Protestantism, despite legislation and trials for heresy, the failure of the Church to reform itself made the Reformation more likely. The records of the period describe the steady growth of Protestantism, culminating in the events of 1559–1560. The sources illustrate the efforts to suppress the Protestants by an authority whose efforts were constantly hindered by the political entanglements resulting f rom growing support for an English rather than a French alliance. Contemporary accounts also THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 1 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST illustrate positive support for the Protestants as seen in iconoclasm and the popularity of contemporary religious songs and ballads. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 8–14 The Reformation of 1560 A combination of religious, economic, and political motives assured sufficient support for the Protestants in 1559, although their success was only assured when Elizabeth of England intervened in 1560. The French, whose pr esence had encouraged many Scots to side with the pro -English Protestants, were expelled from Scotland. On religious and economic issues no such firm conclusion was reached. The Mass and the exercise of authority from Rome were forbidden, but little was done to endow the new Protestant Church or disendow the Catholic Church. One practical difficulty in this respect was the nobles’ possession of most monastic lands and revenues. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 15–16 Issue 2: The Reign of Mary, 1561–1567 Mary’s difficulties in ruling Scotland: religion The Triumph of Protestantism Opinions vary as to the strength of the Protestant movement in Scotland in 1560 but what is certain is that the Catholic Church put up little formal resistance to its rival. Some Catholics remained firm in their faith and tried to stem the Protestant tide but to no avail. Individuals maintained their beliefs while examples of group activity can be observed in various places e.g. some inhabitants of Orkney had Mass said within earsho t of the Reformed Bishop who was too ill to interfere with their actions. Lack of leadership weakened the cause of those Scots who would have preferred the continuance of Catholicism. The enthusiasm aroused by the Protestant Church in many areas is recorded in contemporary sources. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 17–19 Moderation in Reform Church Buildings The moderation of the Scottish Reformation was one of its most striking features. The destruction of religious houses, in most but not all cases, was not due to the Protestants but due to English military operations, neglect in the pre-Reformation period, and the indifference of later times. The policy of 2 THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST the Protestants was to purge the churches of all signs of idolatry while preserving and utilising existing buildings which were necessary for religious uses. While ecclesiastical ornaments were destroyed or sold, the proceeds of sales were frequently used to repair churches or to increase the comfort of parishioners. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 20–26 Personnel The Protestants showed considerable tolerance in their treatment of Catholic clergy. Isolated cases of ill-treatment can be found, but the evidence of cruelty is often more apparent than real, as in the case of the order for all adherents of the old faith to be banished from Edinburgh, which was rescinded almost at once. It proved impracticable to dispossess the Catholic clergy of their benefices so they were allowed to retain two-thirds of their revenues for life, while the Protestant Church was to be maintained from some portion of the remaining one-third. Monks and friars were equally well treated, being allotted pensions and allowed to utilise their quarters for rest of their lives. Concessions made to Catholic clergy on the grounds of old age or ill-health are frequently recorded in contemporary records. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 26–29 Issue 3: James VI and the Relationship between Monarch and Kirk The struggle for control of the Kirk; from regency to personal rule; differing views about the roles of the monarch and Kirk The Programme of 1560 The ‘First Book of Discipline’, although neve r officially approved, indicated the programme which the Reformers would have liked to have seen implemented, in terms of both organisation and discipline in the Protestant Kirk, as well as in their ideals of organised education, and poor relief. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 30-36 The Organisation of the Church General Assembly Little is said in the ‘First Book of Discipline’ about any body comparable to the General Assembly. As far as Knox was concerned, had it not been for the Scots having a Catholic queen, England’s example would have been followed and the Godly prince accepted as head of the Church of Scotland. Instead the THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 3 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST idea of a General Assembly which, on behalf of the whole Christian community, would mirror in its composition the Three Estates or godly magistracy, appears to have met the requirements of the Protestant reformers. With the rise of extreme or ‘Melvillian’ Presbyterianism and its division of church and state the composition of the General Assembly became essentially clerical and claims were made that the authority of the Church was greater than that of the state in ecclesiastical matters. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 37–39 Bishops and Superintendents The ‘First Book of Discipline’ placed the organisation of the Protestant Church in the hands of superintendents. What is disputed is whether or not the office of superintendent was intended to be a permanent one or not. Contemporary evidence suggests that either the office was to be permanent or a short term measure until bishops were appointed. Knox does not appear to have objected to the office of superintendent as such, and his later objections to bishops, in place of superintendents, appe ar to have arisen from his doubts about the suitability of the proposed holders of the office, rather than any antipathy to the office of bishop. Knox eventually agreed to the restoration of bishops, following the settlement at Leith in 1571–1572, and it was not until the acceptance of the ‘Second Book of Discipline’ that the office of bishop was condemned by many Protestants. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 40–44 The Kirk Session Before the Reformation was effected the Protestants possessed a rudimentary organisation at congregation level and with the success of the movement it was decided that this organisation should be extended to all reformed parishes. This body, known as the Kirk Session, consisted of elders and deacons who were to be elected annually (the doctrine of once an elder, always an elder, only appeared with the ‘Second Book of Discipline’). The Session punished moral lapses, especially those not normally punishable by civil courts, and while the Protestants would have welcomed the support of the secular authorities in this respect, they exercised the right of fining, imprisoning and excommunicating offenders against their authority. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 44–46 The Ministry The Admission of Ministers The Protestants laid great stress on the consent of the elders and congregation in the admission of Ministers to office. Equal emphasis was given to the necessity for thorough examination of candidates for the Ministry. 4 THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST The ‘First Book of Discipline’ suggested that the laying on of hands at the ordination of a Minister was to cease. In practice the ceremony appears to have been retained, although some Protestants continued to contend that the laying on of hands was not essential, ‘but ceremonial and indifferent’. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 47–48 The Sustenance of the Ministry The poverty of ministry in the immediate post-Reformation period is one of the most striking features of the new Church. However, not all ministers were poverty-stricken. By the end of the sixteenth century most ministers were reasonably well off. Also, a minister’s means could not be measured in terms of money alone, and the produce of the glebe ensured that the minister would not go hungry. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 49–50 Ecclesiastical Dress Protestant ministers managed to dress to advantage and the General Assembly’s concern over this matter shows that the Protestant Church had not entirely escaped from the problems which had beset the Catholic Church. Blast and Counterblast, p. 51 Issue 4: The Impact of the Reformation on Scotland to 1603 The social, cultural and educational impact of the Reformation on Scotland to 1603 The Programme of 1560 The ‘First Book of Discipline’, although never officially approved, indicates the programme which the Protestants would have liked to have seen implemented, both in terms of organisation and discipline in the new Church, and their associated ideals of organised education and poor relief. Practical considerations largely prevented its implementation and the achievement of its ideals was to prove in many areas incapable of realisation. Education One of the most serious criticisms levelled against the pre -Reformation Church was its failure to provide an educated priesthood. Therefore it is not surprising that the Protestants laid great stress upon education and insisted that all Ministers should be examined as to their qualifications. Particular emphasis was laid upon literacy and the use of books. The Protestants had ambitious plans for the provision of educational facilities. Although Medieval Scotland possessed three universities there was much room for improvement in the provision of schools, while university THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 5 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST education urgently required an overhaul. Lack of finance proved to be an insurmountable obstacle to the realisation of these ambitious plans. Most of the funds the Protestants had earmarked for education fell into other hands, although certain revenues from friaries and prebends were utilised by schools and universities, eventually. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 30–34 Poor Relief One of the many duties largely neglected by the pre -Reformation Church had been that of provision for the poor, while many of the Catholic clergy and religious appeared to grow wealthy. The element played its part in the growth of Protestant opinions and one of the most significant acts of 1559 had been the appearance of the ‘Beggars’ Summons’ which threatened the dispossession of the friars. The Protestants had ambitious plans to provide for the poor from the revenues of the old church but vested interests thwarted their ambitions. All that was achieved in this direction was largely due to piecemeal arrangements, and while the revenues from some friaries were used to meet this necessity this proved to be totally inadequate. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 34–36 Divine Service The Protestants expected that Divine Service would be conducted on week days as well as Sundays, but the principal services would be held on Sundays. Morning and afternoon were to be devoted to worship, but the second session would be primarily devoted to teaching the catechism. Every effort was made to ensure that no possible diversions existed that could prevent congregations from attending weekday and Sunday services. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 52–54 Psalms and Music The Protestants decided to remove all organs from places of worship in order to cleanse parish churches of all ‘monumentis of idolatrye’. However, there is evidence that instrumental music continued to play a part in services, on more than one occasion. Congregations undoubtedly knew their psalter and its harmonies, and this knowledge was increased by the enforcement of acts relating to the possession of Psalm Books and Bibles. The General Assembly exercised strict supervision over the printing of these books. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 55–58 6 THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST Communion The Protestants insisted that the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper was a feast rather than a sacrifice and that the celebration was to take place only on Sundays and then only when there was a preacher present. Th e Sacrament was not to be distributed in any place apart from a parish church. The Catholic practice of Morning Communion was retained with celebrations taking place at a very early hour. As a reaction against the Catholic practice of taking Communion at Easter alone, the Protestants advocated more frequent celebrations of the feast. The large quantities of wine used indicate that large numbers of communicants participated in these celebrations. Congregation members were only admitted to these celebrations on the production of a token. On occasions the large number of communicants meant that the distribution of Communion was spread over two Sundays. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 58–63 Baptism All baptisms in the new church had to be held in parish churches . The Catholic Church had admitted the validity of lay baptism in exceptional circumstances but the Protestants would not allow this under any circumstances. All baptisms had to be administered in church at a time of public preaching. Godfathers were very much in evidence in these baptismal services, and Godmothers were not unknown in the earliest days of the Reformed Church. Blast and Counterblast, pp64–65 Marriage As in the Catholic Church marriages in the Protestant Church were always celebrated in parish churches. Banns continued to be published three times in the parish church(es) of both parties before the marriage but certain relaxations were allowed on the question of marriage within the forbidden degrees. Marriages were solemnised mostly on Sunday mornings, although there were exceptions so long as ‘preaching was joined thereto’. Marriage celebrations resulted in a great deal of merrymaking and Kirk Sessions were constantly occupied in their attempts to keep the festivities within bounds. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 66–67 Burial The Protestants forbade burials within churches and the burial of the dead was to be carried out without any kind of ceremony. Neither reform appears to have been immediately successful. The proposal that Ministers keep death registers met with limited success. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 68–69 THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009 7 BLAST AND COUNTERBLAST Festivals Plays The Protestant banned the celebration of Festivals and Saints’ Days as they believed that they had little or no scriptural authority. However, the opinion of the people was not in step with that of the Church and many traditional festivals continued to be observed, although not necessarily from religious motives. The continued abstention from meat in Lent and on Fridays is worth noting, although the motivation was now economic rather than religious. Blast and Counterblast, pp. 70–76 8 THE AGE OF THE REFORMATION, 1542–1603 (H, HISTORY) © Learning and Teaching Scotland 2009