Evaluating Leadership Outcomes

1

Evaluating Leadership

By Gregory H. Schultz

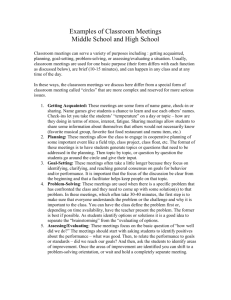

Researchers do not agree on a concise

definition of leadership but concur the definition

is framed by the context in which leadership

exists (Bass, 1990; Kreitner, 1995; Vroom &

Jago, 2007). Many researchers agree that a

compromise of definitions found in the literature

includes some form of social influence that

enables voluntary action in an effort to produce

organizational outcomes (Drucker, 2004;

Kreitner, 1995; Vroom & Jago, 2007). Thus, the

outcome of this article is to describe and

evaluate a methodology to evaluate leadership

outcomes.

An important element of measuring

outcome is to make sure the “right things” are

measured. Leadership evaluation should begin

with the end in mind, including a definition of

what and how leadership outcomes will be

measured (Hannum, 2004; Martineau, 2004).

The outcome of measuring leadership is to

establish a point from which leaders can

improve. Two forms of evaluation exist. The first

form is to collect quantitative information. A

survey instrument makes quantitative

information collection easy. A second form of

data collection is qualitative research. A

highbred approach is to use a mixed method,

which provides the best information since

quantitative data can provide a springboard for

further in-depth information in the form of

interviews (Creswell, 2003).

Before developing a methodology to

evaluate leadership, it is necessary to

understand what leadership is and what may be

worth evaluating. To frame a slightly different

definition then what was provided above, Vroom

and Jago (2007) defined “leadership as a

process of motivating people to work together

collaboratively to accomplish great things” (p.

18). In order to examine what to measure, the

methodology will need specific components

beyond what the definition offers. Vroom and

Jago further established that a) leadership is a

process not a possession, b) leadership

influence is motivation, c) the motivating

components of extrinsic and intrinsic are not

involved, d) the outcome of influence is goal

consensus, and e) “great things” (p. 18) are

outcomes shared by the team and not

necessarily other organization members. The

above definition provides a framework and

implications for leadership evaluation. When

framing leadership outcomes, it may also be

necessary to understand the situational

environment where leadership takes place. A

major component of Vroom and Jago’s research

was to define the position of leadership framed

by the context or situation. The context or

situation enacts a mediating role in the

determination of the optimal leadership process.

Now that a workable understanding of

leadership is established, the context of change

will be examined as function for deploying a

leadership process.

Leading Change and Evaluation

One of the primary outcomes for a

leader is migration to a new end state or the

successful culmination of innovation (Wren &

Dulewicz, 2005). The outcome of innovation is

some incremental difference based on a

reference or starting point. Many change models

provide a recipe of processes or steps that

enable successful change. An examination of

two change models will follow. Each model

defines clarity to the elements or expectations

expected from leaders. Mento, Jones, and

Dirndorfer (2002) highlighted two change

models considered popular in organizational

change including Kotter’s change model and

Garvin’s GE model. Kotter’s model states

leaders should a) establish a sense of urgency,

b) form a guiding coalition, c) create a vision, d)

communicate the vision, e) empower others to

act on the vision, f) plan short-term wins, g)

consolidate improvements, and h) institutionalize

the change. Whereas Garvin’s model defines a

similar set of elements including a) leadership

behavior, b) the need for a shared vision, c) the

shape of the vision, d) commitment, e) making

change last, f) monitoring progress, and g)

change systems and structures.

Comparing both models, each offers a

roadmap for leading change. In contrast,

Kotter’s model examines change very distinct

phases and denotes that failure in any phase

could derail change. Garvin’s model used

Lewin’s theory of unfreezing and refreezing the

change process (Mento et al., 2002). Both

models emphasis organizational change is a

process with distinct inflection points. The

© 2008 by Gregory H. Schultz

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Evaluating Leadership Outcomes

leadership process outlined by Vroom and Jago

(2007) shares distinct characteristics with the

change models highlighted. These

characteristics provide insight for the context or

specific situations that might be used to evaluate

leadership effectiveness.

Measuring Leadership Outcome

Using feedback to evaluate leadership outcomes

Since change is a major function of

leadership and successful change should equal

successful outcome, this section will examine

360-degree feedback as a method of evaluating

leadership outcomes. 360-degree feedback, in

essence, provides a snapshot or depiction of

behavior for some continuum (Alimo-Mecalfe &

Alban-Metcalfe, 2005). The outcome of

successful change is a supporting culture that

has embraced the institutional components of

change. Alimo-Mecalfe and Alban-Metcalfe

pointed out that organizational transformation

enables and drives the norms of the resulting

culture and culminates with a shared vision held

by the culture. Thus, perceptions of followers

should provide feedback about the behaviors

possessed and exhibited by leaders during the

transformational process. 360-degree feedback

provides precise information about leadership

strengths and weaknesses by a cross-section of

organizational representatives (Conger &

Toegel, 2002). Leaders must realize that

feedback is individual perception of respondents

and any advantage is based on how leaders use

the information.

To understand what elements

contributed to successful change and what

dimensions of leadership enabled successful

change, Wren and Dulewicz (2005) explored the

use of 360-degree feedback within the Royal Air

Force. Wren and Dulewicz identified a set of

leadership dimensions and a set of leader

activities found to be most beneficial for

successful change. The high dimensions

include: a) managing resources, b) engaging

communication, and c) empowering teams.

Whereas the most important leadership activities

included: a) a vision of the future state, b)

nurturing the culture, c) establishing early wins,

d) taking responsibility, e) not losing sight of the

big picture, and f) motivating the team. Wren

and Dulewicz were careful to point out that

successful change contains the most important

leadership dimensions and 360-degree

2

feedback offers rater input on the strengths and

weaknesses of each dimension.

Drucker (2004) stated the modern view

of leaders may be single dimensional given the

research in areas of charismatic leaders but

warned that great leaders are not from the same

mold. Thus, evaluating leadership outcome may

require some level of qualitative feedback. As

pointed out earlier, 360-degree feedback is a

good form of qualitative feedback. Martineau

(2004) stated the first critical step in any

evaluation process is to identify key

stakeholders. The right stakeholders for

leadership evaluation are people who have a

stake in the appropriate outcome. The right

stakeholders understand the context or situation

of the applied leadership process. Therefore,

stakeholders are the most relevant players in

defining outcome of the leadership application.

Organizational innovation as an outcome

Drucker (2004) stated leaders must ask

tough questions such as what needs to be done

in the organization. Doing the right things for the

organization does not take into account what the

leader would like to do; rather it focuses on what

makes the organization successful. For

organizations on the technology frontier,

innovation may be a way to measure leadership

success. Profitable innovations may be an

indication that leadership focus is on the future

and that leaders understand the external forces

acting upon their organization.

Researchers agree that measuring

revenue streams offers a tangible method of

evaluating innovation (Lanjouw & Schankerman,

2004; Shapiro, 2006). Shapiro posited,

"[p]ercent of revenue from new products is the

most commonly used measure of innovation" (p.

43). Examining the amount of patents filed

based on the level of research and development

provides a second method to measure

innovation. Patent submission is indicative of the

level or quantity of organizational innovation. In

their research, Lanjouw and Schankerman found

that patent release timing and product demand

had a strong correlation to organizational stock

price variation. The outcome of stock price

variation over time may mean that for some

firms, stock valuation could be a way to measure

periods of innovation. Therefore, organizational

growth and decline may be indicative of the

quality of leadership continuum. Historical

organizational growth and decline based on

stock valuation are tangible quantitative

© 2008 by Gregory H. Schultz

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Evaluating Leadership Outcomes

measures that are easy to located and

manipulate using mathematics.

Evaluating Leadership

Taking qualitative measures like 360degree feedback together with pre-defined

quantitative measures such as profit or stock

valuation offers a well-rounded view of

leadership outcome. Comprehending

perceptions of peers and followers aids in

understanding leadership behavior within the

organization. A multi-rater instrument or 360degree feedback develops a perspective of

leadership behavior from an external

perspective (Conger & Toegel, 2002). In order to

improve, leaders must know how to change

behavior and multi-rater feedback transfers

perceptions about self-knowledge (Conger &

Toegel). However, leader’s willingness to accept

feedback and apply the feedback to appropriate

areas of professional development defines

feedback effectiveness.

Vectors to rate during feedback

sessions include leadership strengths and

weaknesses based on the outcome of the

leadership process. 360-degree feedback

provides precise information about leadership

strengths and weaknesses in a cross-section of

organizational areas (Conger & Toegel). Each

area of feedback should be laden with actual

events that occurred, which will help define the

context.

A problem with 360-degree feedback

includes leadership acceptance of the feedback.

Facteau and Facteau (1998) found that less

3

than perfect scores affected leadership

acceptance of feedback by bringing into

question the leader’s perception of self. The

outcome of leadership evaluation is

developmental in nature. Developmental areas

highlight areas for improvement where leaders

are deficient. Conger and Toegel (2002) found

that leadership improvement resides in the

region between leader self-perception and the

perception of raters. Evaluating leadership

should provide a core understanding of the

qualitative components of leadership processes

including the application of influence coupled

with the quantitative measure of tangible

outcome such as innovation and stock valuation.

Conclusion

Researchers agree that the definition of

leadership is not concise but many frame the

definition within the context in which leadership

exists (Bass, 1990; Kreitner, 1995; Vroom &

Jago, 2007). Using stakeholders that understand

the context aids in leadership evaluation. 360degree feedback provides a qualitative method

to gather information about the leadership

process. Another technique uses quantitative

methods to collect information about

organizational growth and decline by examining

stock variation over time. Qualitative and

quantitative measures together offer a broad

perspective to evaluated leadership. The

evaluation provides correlation to tangible and

intangible components described by Vroom and

Jago’s (2007) perspective on leadership as a

process.

© 2008 by Gregory H. Schultz

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Evaluating Leadership Outcomes

4

References

Alimo-Metcalfe, B., & Alban-Metcalfe, J. (2005). The crucial role of leadership in meeting the challenge of

change. Vision-The Journal of Business Perspective, 9(2), 27-39.

Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Strogdill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research & managerial

applications. (3rd ed.). New York: The Free Press.

Conger, J., & Toegel, G. (2002). Action learning and multi-rater feedback as leadership development

interventions: Popular but poorly deployed. Journal of Change Management, 3(4), 332-348.

Creswell, J. W. (2003). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and

qualitative research (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Drucker, P. F. (2004). What makes an effective executive. Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 58-63.

Facteau, C. L., & Facteau, J. D. (1998). Reactions of leaders to 360-degree feedback from subordinates

and peers. Leadership Quarterly, 9(4), 427-448.

Hannum, K. (2004). Best practices: Choosing the right methods for evaluation. Leadership in Action,

23(6), 15-20.

Kreitner, R. (1995). Management (6th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Lanjouw, J. O., & Schankerman, M. (2004). Patent quality and research productivity: Measuring

innovation with multiple indicators. The Economic Journal, 114(495), 441-465.

Martineau, J. (2004). Laying the groundwork: First steps in evaluating leadership development.

Leadership in Action, 23(6), 3-8.

Mento, A. J., Jones, R. M., & Dirndorfer, W. (2002). A change management process: Grounded in both

theory and practice. Journal of Change Management, 3(1), 45-59.

Shapiro, A. R. (2006). Measuring innovation: Beyond revenue from new products. Research Technology

Management, 49(6), 49(6), 42-51.

Vroom, V. H., & Jago, A. G. (2007). The role of the situation in leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1),

17-24.

Wren, J., & Dulewicz, V. (2005). Leader competencies, activities and successful change in the royal air

force. Journal of Change Management, 5(3), 295-309.

© 2008 by Gregory H. Schultz

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED