Testing the Incremental Validity of the Vroom±Jago

advertisement

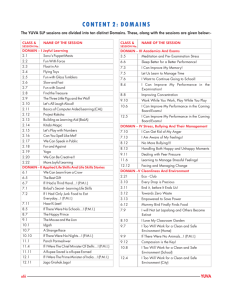

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) Testing the Incremental Validity of the Vroom±Jago Versus Vroom±Yetton Models of Participation in Decision Making RICHARD H. G. FIELD* and J. P. ANDREWS University of Alberta, Canada ABSTRACT In three samples of manager-reported decisions the Vroom±Jago model's predictions were supported. Decisions that more closely ®t the recommended decision method were rated as higher in eectiveness. The model was also found to account for more variance in decision eectiveness than the prior Vroom± Yetton model. It was also found that the Vroom±Jago model's greater precision in situational assessment and derived prescriptions allow for greater discrimination in choice of decision method across all situations. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 11: 251±261 (1998) KEY WORDS Vroom±Yetton; Vroom±Jago; participation; participatory management; leadership Since Tannenbaum and Schmidt's classic 1958 article titled `How to Choose a Leadership Pattern' made explicit that dierent decision methods vary in the amount of participation allowed subordinates, organizational scholars have considered how subordinate decision participation is related to decision eectiveness. At the forefront of this line of inquiry have been the normative models of Vroom and Yetton (1973) and Vroom and Jago (1988a, 1995). The model of Vroom and Yetton took both a situational and a prescriptive stance. In their role as organizational decision makers, leaders were advised to examine the characteristics of each decision situation before making a predecision (Wedley and Field, 1984) of what decision method to select for solving the problem. In its prescriptive form as a decision tree, the Vroom±Yetton model is familiar to most organizational behavior teachers and researchers. In addition to the initial presentation in Vroom and Yetton's book, the model has been tested and studied many times and has been widely reproduced in introductory management and organizational behavior textbooks. Many managers have also become aware of the Vroom±Yetton model through articles in management journals (e.g. Biggs, 1978; Vroom, 1973, 1974, 1976, 1984) and via decision making and leadership workshops (see descriptions in Vroom, 1976; Vroom and Jago, 1988b). * Correspondence to: Richard H. G. Field, Faculty of Business Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R6, Canada. E-mail: Richard. Field@ualberta.ca CCC 0894±3257/98/040251±11$17.50 # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Accepted 20 April 1998 252 Journal of Behavioral Decision Making Vol. 11, Iss. No. 4 Exhibit 1. Attribute questions of the Vroom±Yetton and Vroom±Jago models QR: CR: LI: ST: CP: GC: CO: SI: TC: GD: MT: MD: How important is the technical quality of this decision? How important is subordinate commitment to the decision? Do you have sucient information to make a high-quality decision? Is the problem well structured? If you were to make the decision by yourself, is it reasonably certain that your subordinates would be committed to the decision? Do subordinates share the organizational goals to be attained in solving this problem? Is con¯ict among subordinates over preferred solutions likely? Do subordinates have sucient information to make a high quality decision? Does a critically severe time constraint limit your ability to involve subordinates? Are the costs involved in bringing together geographically dispersed subordinates prohibitive? How important is it to you to minimize the time it takes to make the decision? How important is it to you to maximize the opportunities for subordinate development? Source: Adapted from Vroom and Jago (1988a, pp. 111±112; 229±230). Note: Attributes SI, TC, GD, MT and MD were added to the seven attributes of the Vroom±Yetton model. Exhibit 2. Decision methods AI AII CI CII GII You make the decision yourself using the information available to you at the present time. You obtain any necessary information from subordinates then make the decision yourself.You may or may not tell subordinates about the problem you face. The input provided by them is clearly in response to your request for information. They do not assist in de®ning the problem nor generating or evaluating alternatives. You consult with relevant subordinates individually, getting their ideas and suggestions.You then make the decision. This decision may or may not re¯ect the subordinates' in¯uence. You consult with relevant subordinates in a group meeting, getting their ideas and suggestions. You then make the decision. This decision may or may not re¯ect the subordinates' in¯uence. You share the problem with your subordinates in a group meeting. Together you generate and evaluate alternatives and attempt to reach consensus on a solution. Your role is to facilitate and coordinate the meeting, making sure that critical issues are discussed. You can provide information but must ensure that your views are not given greater weight because of your position. You are willing to accept and implement any solution that has the support of the group. Source: Adapted from Vroom and Jago (1978, p. 152). One key component of the Vroom±Yetton model is that managers are advised to examine seven factors in the decision situation before deciding how much participation to allow subordinates in the making of that particular decision (see Exhibit 1). The other key component is that ®ve decision methods are anticipated, ranging from autocratic to consultative to group decision. These methods are described in Exhibit 2. By answering each of the ®rst seven questions in Exhibit 1, a manager follows a path on the Vroom±Yetton decision tree. At the end of each branch is the feasible set of one or more recommended decision methods for that situation. Decisions that are made using methods that fall within the feasible set prescribed by the model are predicted to result in higher decision quality, subordinate acceptance, and overall eectiveness than decisions that are made with methods that are not within the feasible set. Considerable research has investigated the validity of the Vroom±Yetton model. Field studies (Margerison and Glube, 1979; Paul and Ebadi, 1989; Thomas, 1990), laboratory studies (Field, 1982) and managerial self-reports (Vroom and Jago, 1978; Tjosvold, Wedley and Field, 1986; Field and House, 1990; Brown and Finstuen, 1993) have generally supported the model. In reviewing this literature Vroom and Jago (1988a) estimate that the rate of success of manager behavior conforming to the # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) R. H. G. Field and J. P. Andrews Models of Participation in Decision Making 253 Vroom±Yetton model was 62% whereas it was only 37% when the decision behavior failed to conform to the model. On the basis of this empirical examination of the Vroom±Yetton model, Vroom and Jago (1988a) presented a revised form of the model. These revisions extend the model by allowing a more detailed analysis of the decision situation. The breadth of the situation analysis is increased as twelve situational characteristics are considered rather than seven (see Exhibit 1). The precision of the evaluation of the situation is also increased as ten of these characteristics are ranked on a 5-point scale rather than the yes/no question used in the Vroom±Yetton model. Finally, the Vroom±Jago model is more detailed in its prescriptions. Rather than the decision rules used by the Vroom±Yetton model to produce a feasible set, situational attribute measures are combined in the Vroom±Jago model by a series of structural equations to derive an Overall Eectiveness score for each decision method in the given situation. Overall Eectiveness (Oe ) is de®ned as equal to Decision Quality (Dqual) plus Decision Commitment (Dcomm) less any penalty due to the time taken to make the decision(Dtp), less the cost of making the decision (Cost), plus any developmental bene®ts to subordinates from engaging in the process of making the decision (Devpt), i.e.: Oeff Dqual Dcomm ÿ Dtp ÿ Cost Devpt 1 To use the Vroom±Jago model a manager would analyze the situation by responding to the 12 items listed in Exhibit 1. These responses would then be input into the equations and the overall eectiveness score would be calculated for each method in that situation. In this way the ®ve methods may be ranked from most eective to least eective. The model posits that the higher the Oe ranking, the more eective the decision process will be. Therefore the manager is advised to use the method with the highest score. Available research testing the revised model is scarce and the evidence mixed. In support of the model, Field, Read and Louviere (1990) found that the ®ve situation attributes added by Vroom and Jago all had a signi®cant eect on decision makers' choices of decision method. In addition, Pasewark and Strawser (1994) collected data from 41 audit managers about the decision style used to establish budgeted audit hours, the decision situation attributes, and decision eectiveness de®ned as the dierence in actual audit hours from planned audit hours. Results were supportive of the Vroom±Jago model. Decisions that were made with methods consistent with the recommendations of the model were more eective. Brown and Finstuen (1993) provide evidence that is less supportive of the model. Using self-report data from 36 active duty military ocers they collected information on 132 decision episodes. Each ocer was asked to describe the decision method and situation for two eective and two ineective decisions. They then determined if the decision method used was rated by the model as the best of the ®ve possible methods. Fifteen of the 31 decisions in which the highest rated decision method was actually used were rated as successful by the ocer. Of the remaining 101 decisions made with nonoptimal methods, 52 were rated as successful. The dierence between these two proportions was not signi®cant (w2 1 0.09, ns). This result fails to support the Vroom±Jago model. However, this is not an entirely appropriate test of the model, which provides, for a given situation, a ranking from best to worst of the ®ve decision methods. The better the rank, the better should be the predicted outcome of the decision. Brown and Finstuen's test compared decisions ranked ®rst to decisions ranked second through ®fth Ð a comparison not anticipated by the model. Further, because each ocer contributed multiple decisions, each data point was not independent of the others. This violation of the chi-square test's assumptions can serve to weaken the robustness of the results (Lewis and Burke, 1949). Exploring further, Brown and Finstuen noted that for many decision situations there were one or more other decision processes with Oe scores very close to that of the maximum for that situation. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) 254 Journal of Behavioral Decision Making Vol. 11, Iss. No. 4 They decided to create alternative decision sets for each situation by counting decision processes close to that of the best process as equally recommended by the model. The rule employed was that any decision method with an Oe score within 5% of the maximum score for that decision situation would be included in the alternative set. Retesting, Brown and Finstuen found that 34 of 56 decisions (61%) made with processes in the alternative set were successful, whereas 33 of 76 decisions (43%) made with processes outside the alternative set were unsuccessful. The test of these proportions was signi®cant (w2 1 3.86, p 5 0.05). Brown and Finstuen concluded that `the performance of the Vroom±Jago model is very comparable to that of the Vroom±Yetton feasible set model' (p. 215) when decisions within 5% of the recommendation are included in the recommended decision set. Overall, the Vroom±Jago model is more complex than its predecessor. It is an expert system for managerial decision making that codi®es theory about subordinate participation in decision making into a set of equations (see Vroom and Jago, 1988a, Appendix B). The more complex description of the decision situation may increase the face validity of the Vroom±Jago model as managers see the model as more closely resembling the complexity they face. However, in doing so it loses the intuitive feel that is a major bene®t of the Vroom±Yetton model. In addition, the model has only mixed empirical support. Evidence to date on the Vroom±Jago model indicates that the value of its complexity is not yet proven. Therefore, the purpose of this research is threefold. First, we wish to determine if the model can be supported empirically. Second, we aim to determine whether the additional diagnosticity of the Vroom±Jago model over the Vroom±Yetton model warrants its additional complexity. Third, we seek to determine why the model may outperform the Vroom±Yetton model; that is, whether any increase in the power of the Vroom±Jago model is due to discrimination in ranking alternatives within the feasible set, or whether it is independent of feasible set classi®cation. METHOD Sample 1 Ð Telephone interviews Following previous research we sought data from managers about real organizational decisions. Managers selected at random from organizations in the local white pages telephone directory were asked to `think of a problem that you faced and a decision that you and/or your subordinates made which potentially aected two or more of your subordinates, and that you know the outcome'. Since it has been reported that managers are likely to describe an eective decision (Field and House, 1990), in order to increase the variance of the dependent variable of decision eectiveness half the managers interviewed were asked to describe decisions that turned out to be ineective, that `didn't work out as well as you had hoped'. The manager was asked ®rst to choose which of the ®ve Vroom±Yetton±Jago decision methods was closest to that used to make the decision. The ®ve decision methods were named and described to the manager. Second, the manager was asked to rate the decision situation on the twelve Vroom±Jago situation attribute questions. Each of the twelve Vroom±Jago questions was asked and the scale used for the answer was given. Managers who had diculty with a question were provided a more detailed description of the attribute. The questions, answer scales and attribute descriptions were taken from Appendix A of Vroom and Jago (1988a). Third, managers rated the overall eectiveness of the decision on a 7-point scale where 1 very low, 2 low, 3 somewhat low, 4 average, 5 somewhat high, 6 high, and 7 very high. Finally, several demographic questions were asked. The interview schedule was pretested with 11 managers. These data were not used in later analyses. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) R. H. G. Field and J. P. Andrews Models of Participation in Decision Making 255 Exhibit 3. Decision and demographic descriptive data Demographics: Years as manager Hierarchical level of managera Number of subordinates supervised Percent female managers Decisions reported: Number of subordinates aected Decision methodb Overall eectiveness a Sample 1 Telephone interviews Sample 2 Mail questionnaires Sample 3 Large organizations 13.48 6.17 15.57 23 12.69 5.90 11.99 21 12.71 4.71 17.85 18 5.00 2.96 5.15 7.61 3.86 5.13 8.72 4.15 5.76 Reported on a 7-point scale where 1 is the lowest and 7 is the highest. Decision method is coded as AI 1, AII 2, CI 3, CII 4, GII 5. b In this ®rst sample the rate of agreement to participate was 40%. Interviews were conducted over the telephone at the time of the ®rst contact or with a later call-back and 52 telephone interviews were completed. Descriptive and demographic data are shown in Exhibit 3. The average number of years as a manager was 13.48, average hierarchical level was 6.17, and the mean number of subordinates supervised was 15.57. It was found that the 12 female managers reported a signi®cantly lower hierarchical level than the 40 male managers, a mean of 5.42 versus 6.40 (p 5 0.01). Sample 2 Ð Mail questionnaires After completing 52 telephone interviews, it was decided to create a questionnaire similar to the script for the telephone interviews, and mail it to managers. The questionnaire asked managers to `think of the most recent decision that you and/or your subordinates made which potentially aected two or more of your subordinates, and that you know the outcome was ineective/(eective)'. Half of all the questionnaires mailed asked for an ineective and half asked for an eective decision. A total of 326 managers agreed to be sent a questionnaire. Of these, 108 usable returns were received, a response rate of 33%. It was found that the response rate for the report of an eective decision was higher, at 40% (65 of 163), than for questionnaires asking for an ineective decision report, at 26% (43 of 163). Managers may have found it more dicult to recall ineective decisions or were less willing to invest eort in the description of a failure. It was also found that when an eective decision was asked for, it was so rated (5 or higher on the measure of overall eectiveness) in 64 of 65 decisions reported. A dierent result was found when an ineective decision was requested. Of 43 reported, only 20 decisions were evaluated by the manager as less than or equal to average eectiveness. As a manipulation check of the instructions to report a successful or an unsuccessful decision, selfreported eectiveness was 5.67 in the `eective' condition and 4.30 in the `ineective' condition, a statistically signi®cant dierence (t60 5.41, p 5 0.01). The manipulation therefore served to increase variance on the dependent variable of decision eectiveness. In order to test for possible bias caused by managers rating decision eectiveness in a self-serving manner, the data in Sample 2 were analyzed using initial instructions to recall an eective or ineective decision as the rating of decision eectiveness. It was found that managers asked to recall an eective decision were more likely to report one in which the decision method used fell within the feasible set, and those asked to recall an ineective decision were more likely to report using a method not within the feasible set (w2 1 4.73, p 5 0.05). As in Brown and Finstuen (1993), the data in Sample 2 analyzed # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) 256 Journal of Behavioral Decision Making Vol. 11, Iss. No. 4 in this way did not support the Vroom±Jago model (w2 1 2.11, p ns), unless decision methods that scored within 5% of the maximum Oe were included. In this case subjects asked to recall an eective decision were more likely to report using the maximum (or near maximum) Oe method, and those asked to report an ineective decision were more likely to report using a non-maximum Oe method (w2 2.77, p 5 0.10). These results are very similar to the data collected for previous tests of the models. The conclusion is that managers' ratings of decision eectiveness are not biased. Of the 108 decisions, 79% were reported by males and 21% by females (Exhibit 3). The average number of years as a manager was 12.69, average hierarchical level was 5.90, and the mean number of subordinates supervised was 12. Female managers reported signi®cantly fewer years as a manager than did male managers (10 versus 13, p 5 0.05). Sample 3 Ð Large organizations At this point in the research, the decision was made to approach two large organizations to ask for permission to distribute the decision-making questionnaire to managers within the organization. A total of 122 questionnaires were delivered to the two companies, and 34 completed returns were received, a response rate of 28%. Of the decisions reported, 82% were by males, 18% by females (Exhibit 3). Average number of years as a manager was 13, average hierarchical level was 4.71, and mean number of subordinates was 18. The six female managers had signi®cantly fewer years experience as a manager (7 versus 14 for males, p 5 0.05). RESULTS To allow comparison of the Vroom±Jago model with the Vroom±Yetton model, decision attributes were used to determine the feasible set of decision methods for the particular decision. Because managers rated the seven Vroom±Yetton situation attributes on the 5-point scales used by Vroom± Jago, a manager's answers had to be recoded into the Yes/No format of the Vroom±Yetton model. Answers of `1' or `2' were recoded as `No', `4' or `5' were recoded as `Yes'. Midpoint responses of `3', however, require a judgment. Midpoint scale responses were coded as follows: Quality Requirement Yes; Commitment Requirement Yes; Leader Information No; Problem Structure No; Commitment Probability No; Goal Congruence Yes; Subordinate Con¯ict Yes (Jago, 1993). Then the actual method used was compared to this feasible set and coded as inside or outside (0 Out, 1 In). The Vroom±Jago model was tested by entering manager rated decision attributes into the expert system software (as done by Pasewark and Strawser, 1994) called Managing Participation in Organizations, designed by Vroom and Jago. For each decision, the decision methods were ranked as follows: best 5, second best 4, third best 3, fourth best 2, ®fth best 1. The prediction of the Vroom± Jago model is that the better the ranking, the more eective the decision should be. It is possible to pool the data from the three samples if they are similar enough to be considered as coming from the same population. It would be expected that the ®rst two would be similar, given their method of selection. Managers in Sample 3 were selected from two large organizations in the same city and therefore might share attributes less commonly represented in the wider pool of managers in general. The managers in Sample 3 did not dier from those of Samples 1 and 2 on years as a manager, number of subordinates supervised, percent of female respondents, and number of subordinates aected by the decision (Exhibit 3). Sample 3 managers were of lower hierarchical level than the managers of Samples 1 and 2. This likely re¯ects the fact that they worked in a large organization with # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) R. H. G. Field and J. P. Andrews Models of Participation in Decision Making 257 Exhibit 4. Results of samples 1, 2, and 3 Sample number Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Samples 1 and 2 pooled Samples 1, 2 and 3 pooled Variance explained n Ineective/ eective decision ratioa 52 108 34 160 194 14/38 28/80 3/31 42/118 45/149 rVroom±Yettonb rhoVroom±Jagob 0.05 0.28c ÿ0.06 0.21c 0.19c 3.6% 0.34c 0.18d 0.32d 0.22c 0.25c 6.25% Signi®cance of the dierence ns ns ns ns c a For the purpose of this comparison, eective decisions coded as 5, 6, or 7 on a 7-point scale. Pearson correlations and Spearman rank order correlations for each study are not materially dierent. c p 5 0.01. dp 5 0.05. b many levels and their more middle management status in the organization. In Samples 1 and 2, managers were more likely near the top of smaller organizations. Sample 3 managers also reported decisions that were on average signi®cantly higher in overall eectiveness. This most likely re¯ects the fact that of the 34 questionnaires returned, only 10% were about ineective decisions. The managers of Sample 3 are similar in some ways to the managers of Samples 1 and 2, and dierent in others. Overall, managers in the three samples are similar enough that the data may be studied as a whole. Pooling the data from the three samples, there are a total of 194 decisions. Decision method AI was used 14 times, AII 25 times, CI 44 times, CII 39 times, and GII 72 times. Results for the study are shown in Exhibit 4. Overall, there is support for the Vroom±Yetton model. Decisions made with methods in the recommended feasible set were more eective (r 0.19, p 5 0.01). This ®nding was expected, based on the cumulative research evidence that upholds the model's validity. The data is also supportive of the validity of the Vroom±Jago model. Decisions made with methods ranked as better by the model were more eective (rho 0.25, p 5 0.01). Further, it was found that the Vroom±Jago model added signi®cant variance to that explained by the Vroom±Yetton model. In a hierarchical regression analysis the multiple R of decision eectiveness explained by Vroom±Yetton feasible set agreement was 0.19 (F1,189 7.17, p 5 0.01). The multiple R when the Vroom±Jago ranking was added was 0.27 (F2,188 7.55, p 5 0.01). Examining the mean decision eectiveness scores displayed in Exhibit 5 provides additional support for both models. On average, managers reported signi®cantly higher decision eectiveness when the method used fell within the Vroom±Yetton feasible set than when it did not. Similarly, the mean Exhibit 5. Mean decision eectiveness scores Vroom±Jago Decision set1 Max Oe used Sets 1 and 2 Set 1 Set 2 a 5.73 5.82b 5.64c Vroom±Yetton Max Oe not used a 5.04 4.76b 5.21c Inside feasible set d 5.35 5.45e na Outside feasible set 4.67d 4.67e na a,b,d Signi®cantly dierent at p 5 0.01. Signi®cantly dierent at p 5 0.05. cSigni®cantly dierent at p 0.10. 1Decision set 1 contains those decisions in which the Vroom±Yetton feasible set did not include all ®ve possible methods (n 115). Decision set 2 contains those decisions in which the Vroom±Yetton feasible set included all ®ve possible methods (n 79). e # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) 258 Journal of Behavioral Decision Making Vol. 11, Iss. No. 4 decision eectiveness rating when the method with maximum Oe score is used is signi®cantly higher than when the method used is not the maximum Oe score. Given that the Vroom±Jago model explains signi®cantly more variance in decision eectiveness than the Vroom±Yetton model it is of interest to question the source of that increased prescriptive power. Speci®cally, is the gain due to better discrimination within the feasible set or is it independent of feasible set classi®cation? Of the 194 decision descriptions collected for this research, the method with the highest Oe score fell within the feasible set as determined by the Vroom±Yetton model 168 times. The gain in decision eectiveness associated with the Oe score of the method used was not signi®cantly moderated by the feasible set classi®cation (F4,190 0.391, p ns). However, it is worth noting that in 115 of the decision situations the Vroom±Yetton feasible set included all ®ve decision methods. Clearly, in 59% of the decisions that we sampled the Vroom±Yetton model did not discriminate among decision methods. For the 79 decision situations in which the feasible set did not include all methods, both membership in the Vroom±Yetton feasible set and Vroom±Jago eectiveness rank were signi®cantly correlated with rated decision eectiveness (r 0.27, p 5 0.05 and rho 0.33, p 5 0.01 respectively). But for the 115 decisions in which the Vroom±Yetton feasible set included all ®ve decision methods the Spearman rank-order correlation between the Vroom±Jago method ranking and decision eectiveness was rho 0.23, signi®cant at p 5 0.05. This suggests that decision eectiveness is rated higher when the Oe score is higher and that the Vroom±Jago model provides greater diagnostic power than the Vroom± Yetton model. Further, the data of Exhibit 5 indicates that the mean decision eectiveness score is greater when managers use the maximum Oe method than when they do not, even for those decisions in which the Vroom±Yetton model does not discriminate between the ®ve possible methods (see Exhibit 5, Set 2 data, p 0.10). DISCUSSION This test of the Vroom±Jago model shows that for three separate samples of manager-reported decisions the Vroom±Jago model's ranking of the decision method used correlated signi®cantly with rated overall eectiveness Ð the better the ranking, the higher was the decision's overall eectiveness. Therefore, unlike the result of Brown and Finstuen (1993), this study found evidence for the prescriptive validity of the Vroom±Jago model. We speculate that this is due to using a more appropriate test of the model. The Vroom±Jago model proposes that the higher the Oe score, the more eective the decision. Slight dierences in Oe scores will be re¯ected in slight dierences in rated eectiveness. Hence, it is possible to report highly eective decisions when not using the recommended method. Therefore, classifying methods as optimum/not optimum and eective/not eective does not provide an appropriate test of the model's prescriptions. The amount of variance in decision eectiveness accounted for by the Vroom±Jago model was a relatively low 6.25% (Exhibit 4). This can be cause for concern when it is considered that this model is meant to be a prescriptive tool for managers to help them make better decisions. If only 6.25% of decision eectiveness is explained, then perhaps the model is not powerful enough to warrant its use. There are two arguments that counter this objection. The ®rst is that even small amounts of variance explained can prove important (Prentice and Miller, 1992). The Vroom±Jago model can be used as an expert system to provide advice to a decision maker about how to go about making a particular decision. In this practical use as a programmed decision tool, a small improvement in decision success could translate into large bene®ts for an organization when decisions are of such importance that any small improvement in success rate is crucial. Or, when the model is used routinely, small incremental improvements can add up to large bene®ts over a # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) R. H. G. Field and J. P. Andrews Models of Participation in Decision Making 259 number of decisions. Abelson (1985) has shown that baseball batting skill accounts for less than 1% of the variance in performance in any one at-bat, yet is an important attribute since players bat over 600 times in one season. Similarly, the eect of the Vroom±Jago model might account for a low proportion of decision eectiveness on any one decision, but when manager decisions are accumulated over a year or a career, a small increment in performance is likely to be of great practical importance. The second argument is that the models of Vroom±Yetton±Jago are useful as training tools and as diagnostic devices, without necessarily being used as decision aids. Workshops conducted to explain the theory behind the models can help managers to become more aware of situational contingencies and the possibility of using decision processes that vary in the amount of subordinate participation in dierent situations. With this perspective on the models, it is less important how well they actually predict decision eectiveness. The results reported herein also provide some insight into the source of the increase in variance explained by the Vroom±Jago model over the Vroom±Yetton model. While both models' prescriptions were signi®cantly related to reported eectiveness overall, in 59% of the scenarios reported the Vroom± Yetton model did not discriminate amongst methods. However, for those decisions the Vroom±Jago model's prescriptions were signi®cantly related to reported eectiveness, albeit with less variance explained than for the remaining 41% of decisions. This, combined with the fact that the highest ranked method as determined by Vroom±Jago fell within the Vroom±Yetton feasible set in 87% of the decisions reported, suggests that the Vroom±Jago model provides guidance to managers in selecting from within the feasible sets. Further, both models were more eective when prescribing action in cases in which the feasible set did not include all methods. This suggests that neither model is equally eective across all situations, but that there exists a subset of contexts in which they have greater prescriptive ecacy. There are several issues that must be explored that arise from the nature of this test. First, all data collected was retrospective self-reports by managers. The models are prescriptive in nature, asking the decision maker to consider the situation as it is currently faced, and then to choose an amount of participation by subordinates to use when making the decision. In these tests the decisions had already been made and managers were looking back in time to report how they thought the decision situation existed. It is possible that bias is introduced into these tests of the model if managers, in their retrospections, can not or do not accurately recall the state of the decision situation attributes. A decision maker could, for example, determine that subordinates would accept his autocratic decision, and then be autocratic when solving the problem. If troubles occurred when implementing the decision and subordinates did not accept the decision made, the manager may recall the situation as one where subordinates would not accept his autocratic decision. The passing of time may lead to errors in recall. Further, there may be a recall bias such that managers selectively recalled information that would support the model. However, the model is complex both in the number of situational attributes considered and in the equations that are used to create the model's prescriptions. Even with a good deal of familiarity with the model it is not clear how to respond to the situation attribute questions in order to manipulate Oe scores for decision methods. Second, similar to previously published studies of both Vroom±Yetton and Vroom±Jago models, there is the possibility in these tests of single-source bias, in that decision makers reported both the attributes of the decision situation and the eectiveness of the decision. Independent and dependent variables supplied by the same individual can raise questions about possible percept-percept in¯ation (Crampton and Wagner, 1994). If this were the case then the correlation between the model's prediction and decision eectiveness might be too high. In their review of the Vroom±Yetton model, Vroom and Jago (1988a) noted that the eectiveness of behavior conforming to the model was consistent across studies using ®eld data, laboratory data and self-report data. This suggests that, in this type of study, single source self-report data does not unduly bias the results. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) 260 Journal of Behavioral Decision Making Vol. 11, Iss. No. 4 Third, one must consider the high level of eectiveness of the decisions reported. Earlier self-report tests of the Vroom±Yetton model (e.g. Vroom and Jago, 1978; Brown and Finstuen, 1993) have typically asked a decision maker to categorize decisions as eective or ineective, and to report at least one from each category. This procedure serves to provide required variance on the dependent variable of decision eectiveness. In the tests reported here, managers were asked to report only one decision and to rate its eectiveness on a 7-point scale. Decisions reported tended to be much more of the eective than ineective kind. Average overall eectiveness ranged from 5.15 and 5.13 in the ®rst two samples to 5.76 in Sample 3 (Exhibit 3). Recall bias could be in play here, as managers recall more easily those decisions that were well made and worked out. In addition, we believe that managers are less likely to return the questionnaire if they have to report an ineective decision. Also likely is a time eect. A decision might be ineective through several cycles of being reworked and retried before ®nally being implemented successfully. This decision can be seen to have been ineective several times before ®nally being eective. Looking back allows the manager to recall it as ®nally eective. In sum, these biases serve to reduce the variance of reported decision eectiveness, making it more dicult to ®nd an eect of the models. Our test is therefore a conservative one. If the Vroom±Yetton±Jago models were used in real time by managers, their recommendations might more precisely predict when decisions are ineective. Fourth, in this study managers were not trained in the interpretation of the model's decision situation questions, which may have reduced their understanding of the model's questions and thereby reduced the validity of this test. However, training managers in the models could lead to results supporting them because of a shared understanding of what problem situations are likely to be eectively solved by which decision methods. Previous results using manager self-reports and various levels of manager training (e.g. Vroom and Jago, 1978; Tjosvold, Wedley and Field, 1986; Brown and Finstuen, 1993) supported the validity of the Vroom±Yetton model, as did this study. Therefore, level of training does not appear to determine the results found. Finally, managers were asked which of the ®ve methods were used to make the decision. This misses the point that a decision may involve multiple decision methods and procedures, but was required to test the model as currently prescribed. Future tests could more fully examine the dierent decision methods and combinations of methods used by managers as they go about ®nding solutions to problems. In conclusion, using methods similar to those used earlier to test the Vroom±Yetton model, statistically signi®cant support was found for the Vroom±Jago model in three manager samples. While the Vroom±Jago model is more complex, it accounts for more variance in decision eectiveness. It was also found that the greater precision in the situational assessment and prescriptions derived by the Vroom±Jago model allows for greater discrimination in choice of decision method across all situations. REFERENCES Abelson, R. P. `A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot', Psychological Bulletin, 97 (1985), 129±133. Biggs, S. F. `Group participation in MIS project teams? Let's look at the contingencies ®rst!'. MIS Quarterly, March (1978), 19±26. Brown, F. W. and Finstuen, K. `The use of participation in decision making: A consideration of the Vroom±Yetton and Vroom±Jago normative models', Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 6 (1993), 207±219. Crampton, S. M. and Wagner, J. A., III `Percept-percept in¯ation in microorganizational research: An investigation of prevalence and eect', Journal of Applied Psychology, 79 (1994), 67±76. Field, R. H. G. `A test of the Vroom±Yetton normative model of leadership', Journal of Applied Psychology, 67 (1982), 523±532. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998) R. H. G. Field and J. P. Andrews Models of Participation in Decision Making 261 Field, R. H. G. and House, R. J. `A test of the Vroom±Yetton model using manager and subordinate reports', Journal of Applied Psychology, 75 (1990), 362±366. Field, R. H. G., Read, P. C. and Louviere, J. J. `The eect of situation attributes on decision method choice in the Vroom±Jago model of participation in decision making', Leadership Quarterly, 1 (1990), 165±176. Jago, A. G. Personal communication. 10 September, (1993). Lewis, D. and Burke, C. J. `The use and misuse of the chi-square test', Psychological Bulletin, 46 (1949), 433±487. Margerison, C. and Glube, R. `Leadership decision making in a service organization: A ®eld test of the Vroom±Yetton model', Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62 (1979), 201±211. Pasewark, W. R. and Strawser, J. R. `Subordinate participation in audit budgeting decisions: A comparison of decisions in¯uenced by organizational factors to decisions conforming with the Vroom±Jago model', Decision Sciences, 25 (1994), 281±299. Paul, R. J. and Ebadi, Y. M. `Leadership decision making in a service organization: A ®eld test of the Vroom± Yetton model'. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62 (1989), 201±211. Prentice, D. A. and Miller, D. T. `When small eects are impressive', Psychological Bulletin, 112 (1992), 160±164. Tannenbaum, R. and Schmidt, W. H. `How to choose a leadership pattern', Harvard Business Review, March± April (1958), 95±101. Thomas, J. C. `Public involvement in public management: Adapting and testing a borrowed theory', Public Administration Review, 50 (1990), 435±445. Tjosvold, D., Wedley, W. C. and Field, R. H. G. `Constructive controversy, the Vroom±Yetton model, and managerial decision making', Journal of Occupational Behavior, 7 (1986), 125±138 Vroom, V. H. `A new look at managerial decision making', Organizational Dynamics, 1(4) (1973), 66±80. Vroom, V. H. `Decision making and the leadership process', Journal of Contemporary Business, Autumn (1974), 47±64. Vroom, V. H. `Can leaders learn to lead?' Organizational Dynamics, 4(3) (1976), 17±28. Vroom, V. H. `Re¯ections on leadership and decision making', Journal of General Management, 9 (1984), 18±36. Vroom, V. H. and Jago, A. G. `On the validity of the Vroom±Yetton model', Journal of Applied Psychology, 63 (1978), 151±162. Vroom, V. H. and Jago, A. G. The New Leadership: Managing participation in organizations, Englewood Clis, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1988a. Vroom, V. H. and Jago, A. G. `Managing participation: A critical dimension of leadership. Journal of Management Development, 7(5) (1988b), 32±42. Vroom, V. H. and Jago, A. G. `Situation eects and levels of analysis in the study of leader participation', Leadership Quarterly, 6 (1995), 169±181. Vroom, V. H. and Yetton, P. W. Leadership and Decision Making, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973. Wedley, W. C. and Field, R. H. G. `A predecision support system', Academy of Management Review, 9 (1984), 696±703. Authors' biographies : Richard H. G. Field is a Professor of Organizational Analysis in the Faculty of Business at the University of Alberta. His PhD is in Organizational Behaviour from the University of Toronto. His interests are in leadership and decision making. J. P. Andrews is a PhD candidate in the Organizational Analysis Department at the University of Alberta's Faculty of Business. His interests are in managerial decision making, policy formulation and leadership processes. Authors' address : Richard H. G. Field and Julian Andrews, Faculty of Business Building, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R6 Canada. # 1998 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, Vol. 11, 251±261 (1998)