Littorina subrotunda - USDA Forest Service

advertisement

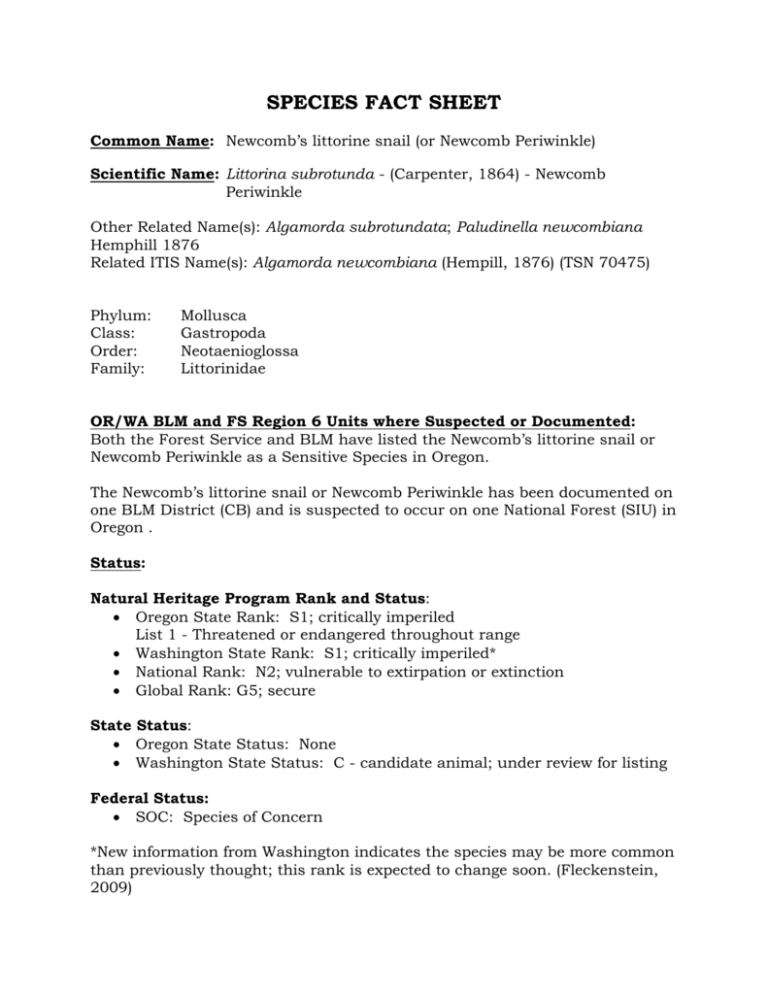

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: Newcomb’s littorine snail (or Newcomb Periwinkle) Scientific Name: Littorina subrotunda - (Carpenter, 1864) - Newcomb Periwinkle Other Related Name(s): Algamorda subrotundata; Paludinella newcombiana Hemphill 1876 Related ITIS Name(s): Algamorda newcombiana (Hempill, 1876) (TSN 70475) Phylum: Class: Order: Family: Mollusca Gastropoda Neotaenioglossa Littorinidae OR/WA BLM and FS Region 6 Units where Suspected or Documented: Both the Forest Service and BLM have listed the Newcomb’s littorine snail or Newcomb Periwinkle as a Sensitive Species in Oregon. The Newcomb’s littorine snail or Newcomb Periwinkle has been documented on one BLM District (CB) and is suspected to occur on one National Forest (SIU) in Oregon . Status: Natural Heritage Program Rank and Status: Oregon State Rank: S1; critically imperiled List 1 - Threatened or endangered throughout range Washington State Rank: S1; critically imperiled* National Rank: N2; vulnerable to extirpation or extinction Global Rank: G5; secure State Status: Oregon State Status: None Washington State Status: C - candidate animal; under review for listing Federal Status: SOC: Species of Concern *New information from Washington indicates the species may be more common than previously thought; this rank is expected to change soon. (Fleckenstein, 2009) Technical Description: Newcomb’s littorine snail is a medium-small marine Prosobranch snail with a thin, conical shell with four or five rounded whorls; operculum present; one pair of tentacles. The shell is smooth, pale in color; sometimes with irregular blotches (Hemphill 1877). The apex is sub-acute, last whorl somewhat inflated, subrimate, with or without three or four longitudinal brown bands; aperture ovate, outer lip thin, inner lip appressed to the columella and somewhat thickened; suture deep; epidermis greenish; operculum with nucleus subcentral with two and one-half whorls (Hemphill 1877). It is one centimeter in length (NatureServe 2009). Figure 1. Photo of Algamorda newcombiana by Nancy Duncan; used with permission. Life History: The biology and ecology of Newcomb's littorine snail are incompletely understood (Larsen et al., 1995). Range, Distribution, and Abundance: This cold-water North Pacific marine gastropod has a southernmost limit in North America in Humboldt Bay, California; but occurs from there north to the Gulf of Alaska. In the U.S. it has been documented in scattered locations along the coast of Washington, Oregon, and northern California (NatureServe 2009). Known sites include the north spit of Coos Bay and Siletz Bay in Oregon; Neah Bay, Mukkaw Bay, Grays Harbor and Willapa Bay in Washington, and Humboldt Bay in California (Jones 1977; Larsen et al., 1995). The current distribution and status of Newcomb's littorine snail is uncertain. Its current range is apparently more extensive and secure in Washington than in Oregon or California, the only other states in which it is found. The species is currently known from only two or three Washington areas and is now more localized in most of those areas than in the past (Larsen et al., 1995). Figure 2. Washington locations where Newcomb's littorine snail, Algamorda subrotundata, has been reported (Larsen et al., 1995) Habitat Associations: Newcomb's littorine snail is found within coastal environments, clinging to rocky shores. It inhabits a narrow zone of intertidal habitat on glasswort/pickleweed (Salicornia virginica) salt marshes at the edges of bays and estuaries where fresh and ocean waters mix (Hinde 1954). It resides above the mean high tide where it is inundated occasionally but infrequently (Hinde 1954, MacDonald 1969, Taylor 1981). Its optimal distribution within its ecosystem is at, or slightly above, mean high tide so that it is submerged in sea water only a few hours per year (NatureServe 2009). Talmadge (1962) reported that L. newcombiana, "...is neither a freshwater nor a true marine gastropod." MacDonald (1969) found it more abundant in less brackish environments. Though tolerant of both fresh and salt water, Newcomb's littorine snail will climb out of either when immersed, and will drown if forced to remain submerged (Larsen et al., 1995). This snail lives on the stems of Salicornia, and possibly other marsh plants. It also lives on substrate such as woody debris and rocks beneath vegetation, where it remains moist and protected from the sun and wind. It feeds on microscopic and macroscopic algae and the vascular plants on and under which it lives (Larsen et al., 1995). It presumably feeds on Salicornia vegetation by rasping the surfaces to remove small particles for digestion (NatureServe 2009). Newcomb’s littorine snail is present year round with possible decreased activity in winter (NatureServe 2009). Figure 3. Habitat for Algamorda newcombiana in Coos Bay, Oregon. Photo by Nancy Duncan; used with permission. Figure 4. Salicornia (pickleweed) microhabitat. Photo by Nancy Duncan; used with permission. Threats: Major threats to Newcomb's littorine snail are habitat loss, pollution, and invasive species. Habitat loss and pollution are primary threats to this species. Habitat in Oregon and California has been threatened by development and pollution, and may be similarly threatened in Washington. Populations and habitats are destroyed as suitable salt marshes are developed or used as dumps for fill, spoils, or waste (Larsen et al., 1995). By 1961, the population in Humboldt Bay in California was nearly extirpated due to habitat loss caused by the dumping and burning of sawdust (Keen 1970). The notice of review (USFWS 1977) concluded: “although recovering after closure of several sawmills, habitat around Humboldt Bay is still threatened by filling and dumping; in Coos Bay, Oregon, it is threatened by log storage on the mud flats, filling and dredging, and the effluent of treated sawdust chips which goes into the bay; in Grays Harbor, Washington, it is potentially threatened by oil spill, pulp mill waste, and municipal waste”. Another threat to the saltmarsh habitat of this species is the invasion and spread of cordgrass (Spartina spp.), a potential threat to the snail's habitat throughout its range. This large introduced grass is of concern due to its ability to displace native plants, degrade wildlife habitat, and alter the geomorphology of estuaries. This exotic plant is out-competing and destroying several native biotic communities (Larsen et al., 1995). Thought to live predominantly on Salicornia in Willapa Bay’s native saltmarsh, Newcomb’s littorine snail may already be experiencing habitat loss as a result of Spartinia alternaflora crowding out native vegetation (Species Account 2008). The ability of Spartina to convert Salicornia salt marshes may be the greatest threat to Newcomb's littorine snails. Conservation Considerations: (Larsen et al., 1995) Monitor and assess activities for impacts on Newcomb's littorine snails and associated habitat. Activities include construction, industrial and municipal uses, recreation, the storage and transport of toxic substances, forest practices, and agriculture. The use of insecticides or herbicides may negatively affect this species. If insecticide or herbicide use is planned for areas where this species occurs, utilize available resources that may be helpful when assessing the use of pesticides and any alternatives. The greatest challenge is to protect its habitat from further destruction and to restore it wherever opportunities are presented. Management Recommendations: (Larsen et al., 1995) Survey and map all Newcomb's littorine snail occurrences. Consider this species in shoreline management or development permits. Monitor the effects of habitat changes on colonies of this species, including grazing and irrigation; insecticide, herbicide, and fertilizer application. Avoid using chemicals where salt marsh habitats might be affected. If insecticide or herbicide use is planned for areas where this species occurs, refer to Appendix A (page A-1) for contacts helpful when evaluating pesticides and their alternatives. Avoid placing fill on habitats; avoid use of treated woods unless shown to have no impact. Avoid off-road vehicle activities that may compact, rut, or otherwise alter the soil, moisture, or vegetative regime on salt marsh habitats. If a spill jeopardizes a significant portion of the state's Newcomb's littorine snail population, collect individuals from threatened areas, along with enough vegetation and substrate to support them. These animals can then be moved to the nearest unoccupied (or underpopulated) area of safe, suitable habitat, or temporarily maintained in captivity until they can be returned to restored habitat. Assess the potential effects of toxic spill cleanup methods and their alternatives, on Newcomb's littorine snails. Assess Forest Practices permit applications for impacts to the Newcomb's littorine snail and its habitat. Avoid introducing exotic plants and animals into areas inhabited by Newcomb's littorine snails. Preparer: Theresa Stone Umpqua National Forest 02 September 2009 Edited by: Rob Huff FS/BLM Conservation Planning Coordinator January 2010 References: Fleckenstein, John. Washington Natural Heritage Program, Zoologist. Personal Communication, 2009. Hemphill, Henry. 1877. Description of a new California mollusk. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. Series 1, Vol 7(1):49. (Lib. note: actual date of publication may be 1876). Hinde, H. P. 1954. The vertical distribution of salt marsh phanerogams in relation to tide levels. Ecol. Monogr. 24(2):209-225. Jones, M. P. (ED.) 1977. 41 Taxa snails, fish, crustaceans proposed. Endangered Species Tech. Bull 11 (2): 1-5. Keen, A.M. 1970. Western land mollusks. American Malacological Symposium. "Rare and Endangered Mollusks." Malacologia 10(1):51-53. Larsen, E.M., E. Rodrick, and R. Milner. 1995. Management Recommendations for Washingtons Priority Species. Volume I: Invertebrates. Washington Department of Wildlife. Olympia, Washington. MacDonald, K. B. 1969. Molluscan faunas of Pacific Coast salt marshes and tidal creeks. The Veliger 11(4):399-405. NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. Talmadge, R. R. 1962. Random notes on Littorina newcombiana Hemphill. Ann. Rep. Amer. Malacol. Union (Pac. Div. 15th Ann. Meeting) (Bull. 29):29. [Abst]. Taylor, D.W. 1981. Freshwater mollusks of California: a distributional checklist. Calif. Fish and Game 67(3):140-163. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. 1977. Proposed endangered or threatened status for 41 U.S. species of fauna. Federal Reg. 42(8): 2507-2512 (1/12/77).