Informational Cascades in IT Adoption

advertisement

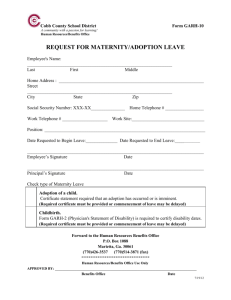

PAYOFF EXTERNALITIES, INFORMATIONAL CASCADES AND MANAGERIAL INCENTIVES: A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK FOR IT ADOPTION HERDING Robert J. Kauffman Professor and Chair, Information and Decision Sciences Co-Director, MIS Research Center Carlson School of Management University of Minnesota Minneapolis, MN 55455 Email: rkauffman@csom.umn.edu Xiaotong Li Assistant Professor of Management Information Systems Department of Accounting and MIS University of Alabama, Huntsville Huntsville, AL 35899 Email: lixi@uah.edu Last revised: May 11, 2003 ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT We have recently observed herd behavior in many instances of information technology (IT) adoption. This study examines the basis for IT adoption herding generated by corporate decisionmakers’ investment decisions. We propose rational herding theory as a new perspective from which some of the dynamics of IT adoption can be systematically analyzed and understood. We also investigate the roles of payoff externalities, asymmetric information, conversational learning and managerial incentives in IT adoption herding. By constructing a synthesis of the critical drivers influencing managers’ IT investment decisions, this study will help business researchers and practitioners to critically address the issues of information asymmetries and incentive incompatibility in firm- and market-level IT adoption. Keywords: Agency problem, asymmetric information, herd behavior, incentives, informational cascades, IT adoption, network externalities, reputations, signaling games. ______________________________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge Yoris Au for helpful discussions on related work. ______________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION 1 In the recent years, there have been many instances of information technology (IT) adoption in which we have observed “herd behavior,” as many investment decisionmakers lost touch with their own cautious value-maximizing approaches to investment decisionmaking, and decided to follow the advice of the many “smart cookies” in the Digital Economy. “Herd behavior,” such as we saw during the height of the DotCom days arises in the presence of differences in the information endowments of decisionmakers in different organizations. Bikchandani and Sharma (2001, pp. 280-281) define herd behavior in terms of three related aspects: (1) the actions and assessments of investors who decide early will be critical to the way the majority will decide; (2) investors may herd on the wrong decision; and, (3) if they do make the wrong decision, then experience or new information may cause them to reverse their decisions, and a herd will be created in the opposite direction. Examples that we have observed 1 The above cartoon was originally published by the New Yorker Magazine in 1972 and is reproduced from Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., and Welch, I. (1996), “Informational Cascades and Rational Herding: An Annotated Bibliography,” Working Paper, Anderson Graduate School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles; Fisher College of Management, Ohio State University; and School of Management, Yale University. Available on the Internet at welch.som.yale.edu/cascades/. 1 include the adoption of price-discriminating electronic auctions, wireless telecommunications technologies, business-to-business electronic market solutions, and enterprise systems software, among others. In other instances, however, considerable inertia seems to have stalled market adoption, as senior managers ask: “Should we wait?” (Au and Kauffman, 2001). Examples include the slow growth of electronic bill payment and presentment technologies and only modest adoption of powerful Internet-based corporate travel reservation systems. Herd behavior has long been studied in other fields, including Finance, Biology, Sociology and Psychology, and especially Economics, where the literature has reached an exceptional depth of coverage of the issues (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch, 1996). In some cases, such as stock market bubbles or the Internet and DotCom mania, herding is driven—in the words of Federal Reserve Bank Chairman, Alan Greenspan—by people’s “irrational exuberance.” Unfortunately, this can be exploited by other rational people in the economy, as Liebowitz (2002) and Schiller (2000) point out. However, recent theoretical and empirical studies suggest that in many other cases herd behavior is rather counterintuitively caused by the decisions of perfectly rational people. Unfortunately, such rational decisions at the individual level sometimes result in significant problems with information transmission, due to people’s unwillingness to pass on information that does not match other information which they have decided to herd on, and the associated welfare losses that arise for others in the marketplace and the economy. In the context of IT adoption, rational herding has the potential to generate several problems. First, valuable information about new technologies is most often lost (or at least poorly aggregated) when IT managers blindly follow the adoption decisions of others. Second, payoff externalities-driven herding makes early adopters’ decisions disproportionately important. It 2 gives other adopters little chance to compare and experience different technologies. Third, managers sometimes intentionally imitate others’ adoption decisions because of their career concerns, and those reputation-motivated decisions usually fail to maximize expected IT investment payoffs. The widespread mimicry in IT adoption and the resultant inefficiencies motivate us to investigate the basis for technology adoption herding generated by corporate managers’ decisions. A common and well-studied justification for IT adoption herding is positive payoff externalities like network externalities. Recent studies have indicated that many technology markets are subject to positive network feedback that makes the leading technology grow more dominant (Brynjolfsson and Kemerer, 1996; Gallaugher and Wang, 2002; Kauffman, McAndrews and Wang, 2000). Because positive network feedback makes a company’s IT adoption return rise as more companies adopt the same technology, it usually gives managers strong incentives to adopt the technology with the larger installed base of users. In addition to the studies of positive payoff externalities, recent research in the area of information economics demonstrates how rational herd behavior may arise because of “informational cascades” (Banerjee 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch, 1992 and 1998) or managers’ career concerns (Scharfstein and Stein, 1990; Zwiebel, 1995). Informational cascades occur when individuals ignore their own private information and instead mimic the actions of previous decisionmakers. Those mimetic strategies are rational when private information is swamped by publicly observable information accumulated over time. This is why informational cascading is sometimes referred to as “statistical herding” (Banerjee, 1992; Ottaviani and Sorensen, 2000). Like informational cascade models, career concerns models have information economics and Bayesian games as their theoretical 3 foundations, but they distinguish themselves by examining rational investment herding through the lens of agency theory (Holmström, 1999). The primary implication of those models is that managers concerned about their reputations may imitate others’ investment decisions to positively influence others’ inferences of their professional capabilities. Although reputational herding decisions are rational for individual managers, they are usually not in the best interests of those companies who hire their managers to maximize investment payoffs. Empirical evidence of herd behavior and imitative strategies has been recently documented in financial investment decisionmaking, stock analysts’ equity recommendations, emerging technology adoption and television programming selection (Hong, Kubik and Solomon, 2000; Hong, Kubik and Stein, 2003; Kennedy, 2002; Walden and Browne, 2002; Welch, 2000). There is also extensive experimental evidence of rational herding and informational cascades in the economics literature (Anderson and Holt, 1996 and 1997; Hung and Plott, 2001). Another recent experimental study of behavioral conformity is by Tingling and Parent (2002), who employ senior IT and business decisionmakers instead of college students are used as subjects. Despite the fast-growing rational herding literature and the pervasiveness of imitative behavior in IT adoption, systematic studies of IT adoption herding are still rare in the IS literature. By synthesizing previous rational herding models, this paper proposes an integrated research framework based on economic theory, and within which the dynamics of IT adoption herding can be better analyzed and understood. The next three sections discuss the underlying theories in greater detail. We investigate the relationship between payoff externalities and IT adoption herding in Section 2. We next demonstrate in Section 3 how the vagaries of information transmission and observational learning can lead to information cascades in technology investment. 4 The problem of managerial incentives in IT investment and adoption decisionmaking is the focus of Section 4. We discuss why agency problems predispose the market to reputational herding in IT adoption. Managerial compensation schemes designed to address those incentive issues are also discussed. Section 5 provides a synthesis of critical theoretical drivers of IT adoption herding and brings the ideas together into a single integrative framework. We provide preliminary thoughts about why stakeholders to IT adoption at different levels (e.g., business process or firm-level investor/decisionmaker, senior executive or member of the board of directors, industry sector promoters or regulators of the economy) may have distinctly different perspectives about , and briefly discusses its potential application. Section 6 concludes the paper with the contributions of this work to ongoing research in IS, and ideas for further research. PAYOFF EXTERNALITIES: DOES ADOPTION HERDING PAY OR HURT? One of a number of different types of payoff externalities that is commonly observed in the IT market is “network externalities” (Economides, 1996; Katz and Shapiro, 1994; Shapiro and Varian, 1999). Network externalities are sometimes referred to as demand-side economies of scale. ( For additional constructs related this area of theory, see Table 1.) 5 Table 1. Key Constructs in the Payoff Externalities Theory Relative to IT Adoption CONSTRUCT Rational IT adoption herding Network externalities Intrinsic and extrinsic network externalities Installed base Path dependencies Tipping equilibrium DEFINITION xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx COMMENTS xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx They stem from the presence of significant technology switching costs and the benefits associated with a large installed base of users of compatible technologies. These and other relevant findings that characterize the Economics literature on network effects and technology switching costs was recently surveyed by Farrell and Klemperer (2001). In the context of IT adoption, network externalities tend to reward herding decisions by increasing the payoffs to IT adopters who associate themselves with the majority. They also decrease the risks that an IT adopter will be stranded in its adoption of an IT that has too small an installed base of users. In technology markets subject to network externalities, IT diffusion processes are often characterized by path dependencies. They represent the situational specifics of irreversible 6 managerial decisions and their impacts on the decisions of others. Many managers believe that network externalities and technology switching costs work in tandem to justify imitative technology adoption. In some cases, strong network effects create a “tippy” technology market in which one technology very quickly emerges as the dominant product because of massive adoption imitation. Under such a winner-take-all tipping equilibrium scenario, the question most managers face is when to jump on the bandwagon, and whether to join the herd. Although herd behavior driven by positive network feedback can be easily justified by individual rationality, it usually leads to obvious information and welfare loss. Companies make their IT adoption decisions mainly based on the installed user bases of competing technologies. Consequently, managers do not concentrate on the intrinsic merits and suitableness of competing technologies, and under many circumstances they do not even have enough time to compare all available technology choices because the technology competition could end very quickly in favor of a technology. So does network externality-driven IT adoption herding pay off? Or does it hurt those firms that adopt this way? At the individual level, each decisionmaker gains by joining the herd and taking advantage of the positive network feedback. However, most decisionmakers lose a chance to deliberate the associated opportunities. Very often, as some have claimed for the VHS video format winning out over the Sony Beta format (Shapiro and Varian, 1999), the market may end up adopting an inferior technology, which will hurt all adopters in the long run. Payoff externalities, as a stand-alone justification for rational IT adoption herding, has its limitations. Strong network externalities may not be so pervasive in the technology market as many IT and business strategists expected (e.g., see Liebowitz, 2002). As a result, imitative technology adoption strategies driven by those illusive network effects are not even individually 7 rational. Moreover, technology managers sometimes choose to adopt emerging technologies with superior performance instead of imitating others by using the dominant technology. Clearly, there is a tradeoff between the future potentials of superior new technologies and the network benefits of current technologies. Adoption herding may not persist or even exist if some firms find that the benefits of exploring new technologies outweigh those of exploiting the dominant technology with network benefits (Lee, Lee and Lee, 2003). It is also worth noting that payoff externalities can be either positive or negative. Unsurprisingly, negative payoff externalities play an important role in mitigating a technology market’s propensity to adoption herding. They are commonly seen in most competitive business environments where downward-sloping demand curves make a company’s IT adoption payoffs decrease as more companies adopt the same technology. Therefore, companies imitate others’ IT investment decisions may be punished by intense ex post competition in the downstream market. Both the fiber cable network glut and the e-commerce gold rush exemplify how severely IT adoption herding may have been penalized by negative payoff externalities. Interestingly, adoption herding sometimes still happens in those situations where negative payoff externalities are evidently present (Kennedy, 2002; Khanna, 1998). Because of these limitations for payoff externalities as a justification for rational adoption herding, we need to investigate other theoretical explanations of firm-level herd behavior in IT adoption. INFORMATIONAL CASCADES: TOO MUCH OR TOO LITTLE INFORMATION? The theory of payoff externalities-driven adoption herding does not sufficiently emphasize two important features that are present in IT diffusion. The first feature is that information asymmetries and information incompleteness are pervasive in emerging technology markets. 8 Different decisionmakers have their own judgments about the business value of a new technology based upon their own private information, and generally no one possesses perfect information in making an individual IT adoption decision. These information structure problems lead to the second feature: to improve the quality of their decisions, decisionmakers keep trying to learn valuable information by observing others’ IT adoption decisions. For those who make their adoption decisions earlier, their actions may reveal their private information to others, which generates information spillovers. These are often referred to as information externalities (Zhang, 1997). (See Table 2 for constructs related to information cascades-driven herding.) Table 2. Key Constructs in the Informational Cascades Theory Relative to IT Adoption CONSTRUCT Information asymmetry Information completeness Information spillover Informational cascade Observational learning Word-ofmouth learning DEFINITION xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx COMMENTS xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 9 Although observational learning can facilitate information conveyance, it also can result in an informational cascade in which most people adopt the same technology independent of their own private information. Similar to the decisionmaking process that appears to be operative in the judicial body depicted in the cartoon in the Introduction to this article, the reason why informational cascades occur with IT adoption is because the information revealed through others’ adoption actions may have accumulated enough to overwhelm a decisionmaker’s imprecise private information (Banerjee, 1992; Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer and Welch, 1992). The opinions of Supreme Court justices, just like the opinions that expressed in a marketplace in which buyers make IT adoption decisions, carry substantial weight with others. In this kind of situation (even with a single Supreme Court justice), the decisionmaker’s action may not depend on his private information. As a result, such decisions actually become incrementally uninformative to others. In fact, it may cause others to rationally disregard their own information and imitate the prevailing adoption decision. The outcome is that the valuable private information of individuals will be lost in such an informational cascade, which simultaneously reduces efficiency because of poor information aggregation in the market. So if informational cascades occur in the technology market, we are likely to observe inefficient outcomes. Some of the things that we frequently observes include IT overbuilding and systems over-investment, and the massive adoption of inferior and poorly understood new technologies. A related intriguing question is whether informational cascades result from too little or too much information. And, how much information is enough? Corporate decisionmakers frequently struggle with too little information to make sound IT investment decisions. That is why they want to gather valuable information from observing other’s adoption actions, and not be too sure about when to apply a stopping rule and decide on their own. Paradoxically, once 10 they engage in observational learning, they may get too much accumulated information, to the extent that it may be strong enough to swamp their private information. As a consequence, an informational cascade will occur and most people will imitate early adopters’ decisions that are rather unfortunately based upon limited information. As two possible mechanisms that cause rational IT adoption herding, informational cascades and network externalities are not mutually exclusive; in fact, they sometimes can be mutually reinforcing (Li, 2003). Informational cascades are generally fragile because they can be stopped or reversed by enough newly-arrived information. For example, many companies will be observed to adopt Technology A over Technology B in a herd when their private information is dominated in an informational cascade, even though everyone knows that the valuable information contained in such a cascade is limited. If some credible information is revealed (by governments or other authoritative agencies, for example) to support Technology B, the adoption cascade can be quickly stopped or reversed. However, informational cascades are far more resilient in the presence of network externalities. Once adoption cascades form, they will be reinforced by later IT adopters who intentionally jump on board to reap the benefits of positive network feedback. The interactive dynamics between the two herding mechanisms have recently been studied by Choi (1997), Hung and Plott (2001) and Li (2003). The strength of informational cascade theory as an explanation for rational IT adoption herding is its emphasis on social learning under information asymmetries. However, social learning can sometimes mitigate a market’s propensity to be influenced by informational cascades. Most informational cascade models assume that decisionmakers can only infer information from observing others’ actions. This assumption exacerbates the information aggregation problem of rational herding. In a simple world where every decisionmaker 11 truthfully tells public his private information, no valuable private information will be lost and the information aggregation problem disappears. In fact, prior innovation diffusion studies have recognized the significant role played by word-of-mouth learning in affecting technology diffusion, as noted by Rogers (1995). Nevertheless, the effectiveness of conversational information sharing in preventing informational cascades should not be overestimated. The major obstacle for effective word-ofmouth learning under many IT adoption scenarios is that each individual decisionmaker’s incentive for truthful information revelation. Potential adopters can benefit from talking with early adopters if what they are told is credible, but who can guarantee the truthfulness of the socalled “cheap talk” (Crawford and Sobel, 1982; Farrell and Rabin, 1996)? In competitive business environments where most IT adoptions occur, individuals may have strong incentives to misinform others through strategic lying or signal jamming, as pointed out by Crawford (2003) and Fudenberg and Tirole (1986). That’s why most researchers who believe that “actions speak louder than words” emphasize observational learning and downplay conversational learning in their informational cascade models. At the market level, informational cascades are more likely to occur when the incentive problems associated with information revelation block credible conversations. At the firm level, decisionmakers’ incentives sometimes cause agency problems that provide another explanation for rational IT adoption herding. MANAGERIAL INCENTIVES IN ADOPTION: PROFITS OR REPUTATION? Since a herd involves a group of decisionmakers, it is natural for researchers to concentrate on understanding the market-level interactive dynamics, such as payoff and information 12 externalities. However, significant developments in agency and incentive theory (Laffont and Martimort, 2002) over the last three decades have nourished a stream of research on rational herding that explores the role of managerial incentives in fostering investment herding. (See Table 3 for definitions of reputational herding and incentive compatibility, two key constructs that figure importantly in the managerial incentives theory literature.) Table 3. Key Constructs in the Informational Cascades Theory Relative to IT Adoption CONSTRUCT Reputational herding Incentive compatibility DEFINITION xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx COMMENTS xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Traditional capital budgeting theory suggests that profit-maximizing companies primarily look at the expected investment payoffs when they make their IT adoption decisions. However, corporate managers hired by a company’s owners or shareholders may have incentives to deviate from the company’s goals and to pursue their own interests when they make their IT adoption decisions. The conflicts of interest, coupled with information incompleteness, can lead to many inefficient outcomes. Some of these are frequently referred to as market-for-lemons problems, adverse selection or moral hazard. In a seminal paper in Economics, Holmström (1999) showed that reputation-concerned managers are very likely to make inefficient investment decisions in the absence of effective mechanisms to align their own interests with those of their companies. In some cases where managerial incentive problems are present, managers may herd solely for reputational purposes in investment decisionmaking. In the influential reputational herding model presented by 13 Scharfstein and Stein (1990), the authors make the case that managers tend to intentionally imitate others’ investment decisions. Intentional herding comes from the belief that managers do not wish to run the risk to be associated with those who are not identified as being in the highly-talented group. In a more specific context, reputation and career concerns are found to be important in promoting security analysts’ herd behavior commonly seen in their stock recommendations or earning forecasts (Graham, 1999; Hong, Kubik and Solomon, 2000). We believe that reputational herding theory has its distinctive advantages in helping us to understand IT adoption herding. Like other important corporate investment decisions, IT adoption decisions are usually made by senior managers. Because their adoption decisions are not immune to agency and incentive problems, they will imitate others’ decisions to enhance their professional reputations if the situation warrants. But unlike most other investment decisions, IT adoption decisions—especially strategic IT adoption decisions—are more susceptible to reputational herding. This is not because a good decisionmaking reputation is more valuable to IT managers like CIOs than to other mangers. Instead, it is because the informational problems are usually more severe. Under many IT adoption scenarios, managers have to make their IT adoption decisions quickly with very limited information. Because IT adoptions are highly specialized tasks that involve a lot of technical details, there are also significant information asymmetries between the decisionsmakers (IT managers) and their supervisors (the firms’s owners or board). Furthermore, the economic payoffs of many IT investments are notoriously difficult to observe or measure in the short run, which gives managers more room reputational gain at the expense of their companies. Most reputational herding studies use signaling (or signal jamming) games in which managers try to positively influence their supervisors’ and the labor market’s posterior beliefs on 14 their capabilities and reputations through their investment decisions. Because firms’ owners or the labor market usually lack concrete evidence to indicate whether an individual IT project will be successful or unsuccessful in the short run, IT managers’ professional reputations will heavily depend on the market consensus that is reached by peer managers or short-term reactions in the stock market. As a result, IT managers that are concerned with their reputations are more likely to exhibit herd behavior in their IT adoption decisions than those who are not. Furthermore, when IT managers are concerned about their career prospects, then imitating the IT adoption decisions of other will be fully rational, if doing so will result in a better reputation. The potential inefficiency and welfare loss stem from the conflicting interests among different parties. Therefore, the key to preventing inefficient reputational herding is to address the issue of incentive compatibility. By offering managers appropriate compensation contracts, firms can provide them with explicit incentives to maximize investment returns. Ideally, firms should make their managers’ compensation contingent on the returns of their investment projects, including those of IT managers who make decisions about IT project investments. Two difficulties arise in the context of IT adoption, however. First, it is usually hard to quantify IT investment payoffs, at least in the short run. Incentives from ambiguously designed performance-based contracts are easily subjugated by the implicit incentives from managers’ career concerns. For example, compensation contracts based on short-term stock price could actually exacerbate the efficiency loss caused by rational investment herding (Brandenburger and Polak, 1996). Second, long-term performance-based compensation, like an option on stock, is thought to be more effective in solving agency problems. However, many IT investments play an instrumental role in strengthening companies’ long-term competitiveness. So the quality of an IT manager’s decision, unlike a chief executive officer’s decision, generally will have less 15 impact on a firm’s overall performance. So long-term performance, when it is used as a basis for compensation, must be significant enough to dominate a manager’s gains from reputation building. However, this usually makes these compensation schemes very expensive to implement. This problem deserves the attention of IS researchers, who should study how to overcome these difficulties in designing optimal incentive contracts for managers who make IT adoption decisions. A SYNTHESIS OF CRITICAL DRIVERS IN ADOPTION HERDING One of the primary determinants of the value of the body of theoretical knowledge that we have proposed for explaining observed IT adoption phenomena is the extent to which we are able to identify when its application becomes effective. In this section of the paper, we provide the basis for a framework that permits us to evaluate the applicability and the quality of the insights that the theory offers for herding in different IT adoption settings. Our framework cuts the alternative theoretical perspectives with levels of analysis that represent the possible stakeholders in different IT adoption settings. Framework Preliminaries We need to address two issues in developing our theoretical framework for IT adoption herding. First, almost all the rational herding models in the literature study investment herding in generic investment settings. Although studying herd behavior in generic investments increases the generality of results, it sometimes fails to capture the distinctive features of certain types of investment like IT adoption. So our framework emphasizes the uniqueness of IT investments to provide more in-depth and relevant analysis of adoption herding. Table 4 shows how certain features of IT investments can increase the chances for rational investment herding to occur. [Insert Table 4 here] Second, our integrated framework recognizes the difference and 16 relationships among the three explanations for rational investment herding. As one major goal of our framework is to allow IT adoption herd behavior to be studied from appropriate theoretical perspective, it is important for us to understand the strength and weakness of each explanation under different IT adoption scenarios. We provide a comparison of the three theoretical explanations for IT adoption herding in table 5. [Insert Table 5 here] o 2nd paragraph: discussion of the stakeholder levels, motivation for that, what leverage looking at IT adoption problems at these levels of analysis creates for insights, why stakeholder level enable us to focus on different strategy perspectives relative to the different herding related theories xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 17 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxx An Evaluative Framework for Assessing Herding Theories of IT Adoption □ 3 paragraphs for this section o 1st paragraph: introduce the framework with a brief couple sentences and then give the table o 2nd paragraph: explain the contrasts that the framework depicts, answer question about why this framework provides a basis for figuring out which of the herding behavior theories is the most appropriate to use in the interpretation of the observed adoption phenomena in real world settings o 3rd paragraph: explain the structure of a mini-case analysis in general terms using the framework; provides an opportunity to tell reader how to think about our “results”— how we will sell the quality of the framework dimensions in terms of the insights it offers Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 18 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 19 Table 6. An Evaluative Framework for the Alternative IT Adoption Herding Theories THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE Payoff externalities Informational Cascades Managerial incentives BUSINESS PROCESS LEVEL/ IT ADOPTER, INVESTOR Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx FIRM LEVEL / BOARD OF DIRECTORS, SENIOR MGMT xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx INDUSTRY SECTOR / STANDARDS GROUP ECONOMY LEVEL / REGULATOR xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 20 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Four Applications of the Evaluative Framework for IT Adoption Herding Behavior xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx (1) Payoff Externalities-Focused IT Adoption: The Case of Wi-Fi Hotspot Adoption. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 21 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx (2) Informational Cascades-Influenced IT Adoption: ICQ and Microsoft Messenger. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 22 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx (3) Managerial Incentives-Influenced IT Adoption: Morgan/Reuters and Riskmetrics. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 23 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx (4) A Mixed Theoretical Interpretation: Micropayment Solutions on the Internet. xxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 24 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Discussion Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxx Xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx 25 xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx CONCLUSION This study provides a new theoretical framework for rational IT adoption herding as basis for understanding some observed forms of IT adoption and the related fundamentals of managerial decisionmaking for IT investments. Herding, as a type of human imitative behavior, tends to result rather naturally from an individual’s imperfect reasoning and cognitive capabilities with respect to the costs, benefits and risks associated with an IT investment. Au and Kauffman (2003) have argued that many inefficient IT adoption decisions can be attributed to the adopters’ bounded rationality. Thus, it will be helpful to explore some of the potential behavioral justifications of observed investment decision herding under certain circumstances (Schiller, 1995). We also believe that the rational herding theory synthesized in our framework is likely to be very useful in many settings where bounded rationality plays a significant role. In fact, many problems associated with bounded rationality can be studied in fully rational models with imperfect information and vice versa (Conlisk, 1996). By formally analyzing IT adoption herding in a somewhat simplified rational world, we are able to pay attention to the relevant information and incentive problems, without sacrificing the real world applicability of most of the managerial insights that will be generated. 26 The reader should not interpret our exposition in this article as a basis for rationalizing the herd behaviors that are commonly observed in IT investment decisionmaking. Nevertheless, our rational herding framework suggests payoff externalities, informational cascades and managers’ career concerns as three interrelated explanations for the kinds of imitative decisionmaking behaviors that are observed in IT adoption. We investigated network externalities, observational learning and managerial incentives as critical drivers influencing managers’ IT investment decisions. By doing so, we demonstrated the relevance and the importance of our proposed framework to academic researchers, business strategists and IT investment managers. Instead of introducing various rational herding models as standalone theories, instead we emphasized their inherent relationships in an attempt to acquire more distinctive insights for IT adoption herding. For example, we showed why an adoption herd is much more likely to form in a market for an emerging technology market, where information asymmetries and network effects come into play. We also demonstrated why reputational herding is more common in IT adoption processes where agency problems are compounded by severe information problems. This paper presents a research framework within which IT adoption herding can be systematically studied. We believe that future studies within this framework will not only enhance our understanding of herd behavior in IT investment, but also offer insights and contributions to the rational herding literature in Economics. Most informational cascade models downplay the importance of conversation and information sharing across firms because of the credibility issue. However, word-of-mouth communications are usually very useful in IT diffusion and social learning in general (Ellison and Fudenberg, 1995; Rogers 1995), and the growing literature on “cheap talk” in Economics also sheds light on the effectiveness of conversational learning in strategic interactions (Crawford and Sobel, 1982; Farrell and Rabin, 27 1996). So future studies that explore the role of conversation in IT adoption herding have the potential to inform the herding literature by generalizing the prior informational cascade models. Future studies of IT adoption herding can also provide additional insights related to the theory of reputational herding. In most reputational herding models that we have seen to date, the outcomes of managers’ investment decisions are observable ex post in a mechanistic manner. So the labor market and firm owners can infer managers’ capabilities through Bayesian updating. However, as we pointed out earlier, many IT projects are strategically instrumental to the firms that invest in them, and yet their payoffs are hard to measure in the short run. This complicates the inference process that leads to managerial decisions about IT investments, and thus requires the extension of reputational herding models so that they will yield more useful insights in this managerial context. Finally, we believe that the framework proposed in our study can also make contributions to the IS literature in some contexts other than IT adoption. For example, we frequently observe herd behavior in IS curriculum design, research topic selection, consumer online shopping patterns, IT firms’ advertising campaigns, R&D spending in developing certain kinds of information systems, and so on. The applications are varied and interesting it turns out. Our study suggests that IS researchers ought to pay close attention to a number of related issues when they study a decisionmaker’s behavior in those contexts. The first issue is payoff interdependence. It is important to try to figure out whether a decisionmaker’s decision will hurt or benefit others who make the same decision. The second issue is information gathering through learning. In this case, it is useful to understand whether a decisionmaker can learn information from the similar decisions of others, and whether the information gathered is credible. The third issue is the incentives of different stakeholders. Here, we want to know 28 whether there are conflicts of interest among the different stakeholders, and if so, whether a specific decisionmaker will have sufficient incentive to pursue her own interests at the expenses of other stakeholders. Our future research will take up some of these issues. REFERENCES [1] Anderson, L., and C. Holt (1996) “Classroom Games: Information Cascades,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 4,187-193. [2] Anderson, L., and C. Holt (1997) “Information Cascades in the Laboratory,” American Economic Review, 87, 5, 847-862. [3] Au, Y., and R. J. Kauffman, (2001) “Should We Wait? Network Externalities and Electronic Billing Adoption,” Journal of Management Information Systems, 18, 2, 47-64. [4] Au, Y., and R. J. Kauffman, (2003) “What Do You Know? Rational Expectations in IT Adoption and Investment,” working paper, MIS Research Center, Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. [5] Banerjee, A, (1992), “A Simple Model of Herd Behavior,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, 3, 797-818. [6] Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D. and Welch. I. (1992), “A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades,” Journal of Political Economy, 100, 5, 992-1026. [7] Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., and Welch, I. (1996). “Informational Cascades and Rational Herding: An Annotated Bibliography,” Working Paper, Anderson Graduate School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles; Fisher College of Management, Ohio State University; and School of Management, Yale University. Available on the Internet at welch.som.yale.edu/cascades/. [8] Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D. and Welch, I. (1998), “Learning from the Behavior of Others: Conformity, Fads, and Informational Cascades,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 12, 3, 151-170. [9] Brandenburger, A., and B. Polak (1996), “When Managers Cover Their Posteriors: Making the Decisions the Market Wants to See,” Rand Journal of Economics, 27, 3, 523-541. [10] Brynjolfsson, E., and C. Kemerer (1996), “Network Externalities in Microcomputer Software: An Econometric Analysis of the Spreadsheet Market,” Management Science, 42, 12, 1627-47. [11] Choi, J. P. (1997), “Herd Behavior, the “Penguin Effect,” and the Suppression of Informational Diffusion: an Analysis of Informational Externalities and Payoff Interdependency,” Rand Journal of Economics, 28, 3, 407-25. [12] Conlisk, J. (1996), “Why Bounded Rationality?” Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 669700. [13] Crawford, V., and J. Sobel (1982), “Strategic Information Transmission,” Econometrica, 50, 6, 1431-1451. 29 [14] Crawford, V. (2003), “Lying for Strategic Advantage: Rational and Boundedly Rational Misrepresentation of Intentions,” American Economic Review, 93, 1, 133-149. [15] Economides, N. (1996), “The Economics of Networks,” International Journal of Industrial Organization, 16, 4, 673-699. [16] Ellison, G., and D. Fudenberg (1995), “Word-of-Mouth Communication and Social Learning,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 1, 93-125. [17] Farrell, J., and M. Rabin (1996), “Cheap Talk,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10, 3, 103-118. [18] Farrell, J., and P. Klemperer (2001), “Coordination and Lock-in: Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects,” Handbook of Industrial Organization, Volume 3, North Holland: Amsterdam, Netherlands. [19] Fudenberg, D., and J. Tirole (1986), “A Signal-jamming Theory of Predation”, Rand Journal of Economics, 17, 3, 366-376. [20] Gallaugher, J., and Y. Wang (2002), “Understanding Network Effects in Software Markets: Evidence from Web Server Pricing”, MIS Quarterly, 26, 4, 303-327. [21] Graham, J. (1999), “Herding Among Investment Newsletters: Theory and Evidence”, Journal of Finance, 54, 1, 237-269. [22] Holmström, B. (1999), “Managerial Incentive Problems: A Dynamic Perspective,” Review of Economic Studies, 66, 1, 169–182. [23] Hong, H., J. Kubik and A. Solomon (2000), “Security Analysts’ Career Concerns and Herding of Earnings Forecasts,” Rand Journal of Economics, 31, 1, 121-44. [24] Hong, H., J. Kubik and J. Stein (2003), “Social Interaction and Stock-Market Participation,” Journal of Finance, forthcoming. [25] Hung, A., and C. Plott (2001) “Information Cascades: Replication and an Extension to Majority Rule and Conformity-Rewarding Institutions,” American Economic Review, 91, 5, 1508-20. [26] Katz, M., and C. Shapiro (1994), “System Competition and Network Effects,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8, 2, 93-115. [27] Kauffman, R., McAndrews, J. and Y. Wang (2000), “Opening the “Black Box” of Network Externalities in Network Adoption,” Information Systems Research, 11, 1, 61-82. [28] Kennedy, R. (2002), “Strategy Fads and Competitive Convergence: An Empirical Test for Herd Behavior in Primetime TV Programming,” The Journal of Industrial Economics, L, 1, 57-84. [29] Khanna, N. (1998), “Optimal Contracting with Moral Hazard and Cascading,” Review of Financial Studies, 11, 3, 559-596. [30] Laffont, J., and D. Martimort (2002), The Theory of Incentives: The Principal-Agent Model, Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ. [31] Lee, J., Lee, J., and H. Lee, (2003), “Exploration and Exploitation in the Presence of Network Externalities,” Management Science, forthcoming. [32] Li, X. (2003), “Informational Cascades in IT Adoption,” Communications of the ACM, forthcoming. 30 [33] Liebowitz, S. (2002), Rethinking the Network Economy: The True Forces That Drive the Digital Economy, Amacom Publishing: Saranac Lake, NY. [34] Ottaviani, M., and P. Sorensen (2000), “Herd Behavior and Investment: Comment,” American Economic Review, 90, 3, 695-704. [35] Rogers, E. (1995), Diffusion of Innovations—4th Edition, Free Press: New York, NY. [36] Scharfstein, D., and J. Stein (1990), “Herd Behavior and Investment,” American Economic Review, 80, 3, 465-479. [37] Schiller, R. (1995), “Rhetoric and Economic Behavior: Conversation, Information and Herd Behavior,” American Economic Review, 85, 2, 181-185. [38] Schiller, R. (2000), Irrational Exuberance, Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ. [39] Shapiro, C., and H. R. Varian (1999), Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy, Harvard Business School Press: Cambridge, MA. [40] Tingling, P., and M. Parent (2002), “Mimetic Isomorphism and Technology Evaluation: Does Imitation Transcend Judgment?” Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 3, 113-143 [41] Walden, E. and G. Browne (2002), “Information Cascades in the Adoption of New Technology,” in F. Miralles, J. Valor, and J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Proceedings of the TwentyThird International Conference on Information Systems, Barcelona, Spain, December 2002, 435-443. [42] Welch, I. (2000), “Herding Among Security Analysts,” Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 369-96. [43] Zhang, J. (1997), “Strategic Delay and the Onset of Investment Cascades,” Rand Journal of Economics, 28, 1, 188-205. [44] Zwiebel, J. (1995), “Corporate Conservatism and Relative Compensation,” Journal of Political Economy, 103, 1, 1-25. 31 Table 4. Rational Herding in Generic Investments and IT Investments Payoff Externalities Driven Herding Informational Cascades (Statistical Herding) Reputational Herding Generic Investments IT Investments Investment herding may arise when there are strategic complementarities among investors who make similar decisions. However, negative externalities may curb investment herding in many competitive environments. Decision-makers imitate others’ investment decisions when their private information is overwhelmed by the information acquired through observational learning. Many IT markets are subject to network externalities, a type of positive payoff externalities. Network effects and significant IT switching costs are the driving forces behind many instances of IT adoption herding. Instead of helping their companies to maximize investment returns, Managers imitate others’ decisions to build their reputations and to maximize their own human capital returns. Information incompleteness and information asymmetries in the IT market make observational learning important for decision-makers, and thus increase the possibility of an informational cascade. The financial returns of most IT investments are hard to measure in the short run, which creates more implicit incentives for managers to engage in investment herding when situations warrant. Table 5. A Comparison of Three Explanations for IT Adoption Herding Network-effect-driven Herding Models Informational Cascade Models Reputational Herding Models Theoretical Foundation Payoff interdependency and strategic complementarities Information economics and Bayesian learning Aspects of IT Adoption emphasized Model Strength IT switching costs, network externalities and technology compatibilities. Many IT markets are subject to network feedback. These herding models are generally more intuitive and robust. Model Weakness Hard to explain herding in situations where network externalities are weak or negative payoff externalities are strong. Information externality and social learning in IT adoption These models rigorously demonstrate how herding arise because of Information asymmetries and the associated learning problems. Simplified assumptions of market information structure and learning processes make these models unrealistic in some settings. Information economics, contracting and agency theory Managers’ implicit incentives and career concerns in IT adoption These models show that herding may be caused by incentive problems, which builds a bridge between the agency theory and the rational herding theory. The conditions that lead to herding are more complex and less obvious. Most models only deal with very simple investment settings.