Appendixes_HICS

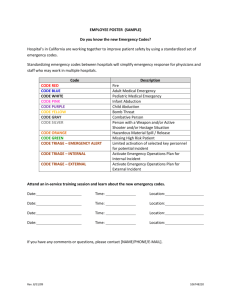

advertisement