The WTO and Trade Economics: Theory and Policy

advertisement

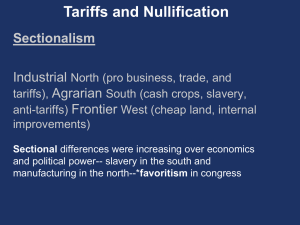

WTO E-Learning WTO E-Learning – Copyright © August 2012 The WTO and Trade Economics: Theory and Policy 1 Introduction This is a multimedia course on The WTO and Trade Economics: Theory and Policy. The course comprises this explanatory text, Frequently Asked Questions and self-assessment quizzes which you can use to measure your understanding of their course. It is also supported by a video presentation of this material entitled "The WTO: Economic Underpinnings". Aim of this presentation The aim of this multimedia presentation is to provide a theoretical background for understanding the effects of trade liberalization and those of protection. We will try to understand also why countries pursue polices of trade liberalization within the context of the WTO, that is why countries negotiate with each other and commit to bound tariffs, for example, rather than liberalizing unilaterally. The presentation is divided into four parts. In the first part I will be providing some insights on what are the most important results of theoretical literature on international economics on the effects of trade liberalization. I. Gains from Trade In particular, initially I will be looking at gains from trade in different setups, ranging from situations where countries trade because they are different in their level of technology, to situations where they are different because of their different endowment factors – different endowments in capital, labour or land. And finally, two situations where countries trade even when they are similar. II. Income distribution Effects In all these cases, I will explain that there are gains from trade, but that trade may, at the same time, have income distribution effects. So that, within each country, there will be some groups that make gains and some other groups that may lose. Trade liberalization also entails adjustment costs. We will explain what does this mean and we will look at what governments can do to minimize these adjustment costs. III. Trade policy and development In the third part, we will look at the evidence on the importance of trade liberalization for development. IV. Need of a multilateral commitment In the last part, we will explain the rationale behind engaging in multilateral negotiations and commit trade liberalization to international agreement. 1 Table of contents I. II. III. GAINS FROM TRADE .......................................................................................... 3 I.A. THE THREE MOST IMPORTANT INSIGHTS FROM THE THEORY OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE ..... 3 I.B. WHERE DO THESE GAINS COME FROM? .......................................................................... 3 INCOME DISTRIBUTION EFFECTS ........................................................................... 7 II.A. TRADE BETWEEN SIMILAR COUNTRIES ........................................................................... 7 II.B. ADJUSTMENT COSTS .................................................................................................. 10 TRADE POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT....................................................................... 12 III.A. WHAT ARE THE INSTRUMENTS OF TRADE POLICY? ......................................................... 12 III.B. WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF AN IMPORT TARIFF? ............................................................... 13 III.C. WHY DO GOVERNMENTS IMPOSE IMPORT TARIFFS? ....................................................... 14 III.C.1. THE TERMS-OF-TRADE ARGUMENTS FOR PROTECTION ....................................... 14 III.C.2. INFANT INDUSTRY ARGUMENT FOR PROTECTION............................................... 15 III.C.3. STRATEGIC TRADE POLICY ARGUMENT ............................................................. 15 III.C.4. OTHER ARGUMENT FOR PROTECTION ............................................................... 16 IV. NEED OF A MULTILATERAL COMMITMENT ............................................................... 17 IV.A. IS THERE A REASON FOR COMMITTING TO MULTILATERAL LIBERALIZATON? .................... 17 IV.A.1. TIME INCONSISTENCY .................................................................................... 18 IV.A.2. OTHER REASONS FOR MULTILATERAL LIBERALIZATION ...................................... 18 V. CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................... 20 2 I. I.A. GAINS FROM TRADE THE THREE MOST IMPORTANT INSIGHTS FROM THE THEORY OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE Let's start with what the theory of international trade tells us about the effects of trade liberalization. 1. There are gains from trade The three most important results of international trade theory are: one, that there are gains from trade; the second one is that when countries sell goods or services to each other, this exchange is always beneficial; and the third, that two countries that trade will benefit from trade even if one of them is more efficient than the other one at producing everything. 2. Trade is mutually beneficial Therefore, not only are there gains, but there are gains for both countries. At the same time, while nations generally gain in aggregate from international trade, it is quite possible that international trade may hurt particular groups within a nation. 3. Trade has income distribution effects, but gains outweigh losses Therefore there are income distribution effects, some groups, some people, will gain, some people will loose and it is very likely that the loosing part of the society will put pressure on the government to pursue protectionist policies, even if overall gains out weigh overall losses. I.B. WHERE DO THESE GAINS COME FROM? GAINS FROM BETTER UTILIZATION OF RESOURCES Economic theory suggests that gains from trade can come from better utilization of resources. ... from specialization What does trade do? Trade allows countries to specialize in the production of the goods that they can produce relatively MORE efficiently and import the goods that they produce relatively LESS efficiently. The exchange of these goods benefits both countries. … from exploitation of economies of scale Gains from better utilization of resources may also come from the fact that trade allows firms to produce on a larger scale. When barriers to trade are eliminated, firms will face the demand of a larger market. Therefore, firms will be able to choose to produce at a more efficient level of production, and save costs. These lower costs will benefit the country as a whole. 3 Gains from specialization Let's now turn to the analysis of the gains from specialization in a little bit more detail. Everybody probably understands that if a country, which is very efficient in producing computers, trades with another country which is very efficient in producing roses, then it is probably to their benefit that the country more efficient in computers produces and exports computers, while the other country produces and export roses. But, what about a country that is more efficient in producing both – computers and roses – trading with a country that is less efficient in the production of both? Is trade still beneficial? – the important result from the theory is that there are GAINS from trade and that BOTH countries gain from trade. These gains will arise from each country specializing in the production of the good for which they have a comparative advantage. Comparative advantage (CA) What does comparative advantage mean? Economists say that a country has a comparative advantage in producing a certain good, if the opportunity costs of producing that good in terms of other goods, is lower in that country than it is in the other country. Note that while defining comparative advantage, we have introduced a new term: "opportunity cost". Opportunity cost What is the opportunity cost? – The opportunity cost of a certain good, let's say roses, in terms of another good, let's say computers, is the number of roses that could have been produced with the resources used to produce a given number of computers. Opportunity costs differ across countries because of differences in technologies. Theory of comparative advantage The theory of comparative advantage states that when two countries specialize in producing the good in which they have a comparative advantage, both economies gain from trade, even if one country has an absolute advantage in both goods. In particular, each country will export the good for which they have a comparative advantage. 1. Specialization from technological differences: the Ricardian Model The best way to understand the idea of comparative advantage is through a specific example – a model that demonstrates this. A model of comparative advantage that relies on differences of labour productivity was first introduced in the early nineteenth century by an economist named David Ricardo, and therefore it is also referred to as the Ricardian Model. In its simplest form the Ricardian Model can be shown with the following example: Suppose that there are only two countries in the world, Country A and Country B – and two sectors – roses and computers. A worker employed in the roses sector would produce five million roses in Country A, and eight million roses in Country B. Another worker employed in the computer sector would produce 200 computers in Country A and one thousand computers in Country B. In other words, whatever the sector, one worker would produce more units of each good when employed in Country B. In this case, Country B has an absolute advantage in the production of both goods. 4 Roses Computers Country A 5 million 200 Country B 8 million 1,000 What about comparative advantages? Let's look at the opportunity costs for each country in terms of roses, of giving up the production of a thousand computers. For Country B the opportunity costs, in terms of roses, of producing one thousand computers less, is eight million roses. What about Country A? If Country A had to produce one thousand computers, it would have to employ five people in the computer sector, because each employee produces only two hundred computers in Country A. In terms of roses, this would imply a cost of 25 million roses. To sum up, while in Country B the opportunity costs of one thousand computers is eight million roses, in Country A the opportunity costs of one thousand computers is 25 million roses. Since the opportunity costs, in terms of roses, of producing computers are lower in Country B, Country B has a comparative advantage in computers, while Country A has a comparative advantage in roses. The theory of comparative advantage tells us that if Country A and B open up to trade, then Country A will specialize in the production of roses and Country B will specialize in the production of computers. What will be the effect of specialization? …the Ricardian Model Changes in output from specialization: Roses Computers Country A +10 million -400 Country B -8 million +1,000 TOTAL +2 millions +600 Specialization increases global production of both goods. All countries can gain from trade. Suppose now that in Country A two workers are moved from the production of computers to the production of roses. This implies that Country A would produce four hundred computers less, and will produce ten million roses more. Suppose also that at the same time, Country B will move one worker from the production of roses to the production of computers, therefore Country B would produce eight million roses less and one thousand computers more. Overall the global production of roses will increase by two million units. This is because there will be an increase of ten million roses in Country A and a reduction of eight million in Country B. In the computer sector there would be six hundred computers more produced globally. One thousand computer more produced by Country B and four hundred computers less produced by Country A. Since specialization increases the global production of both goods, all countries can gain from trade. Trade makes available to each country a higher quantity of each of the goods. 5 Obviously the Ricardian Model is a very simple simplified model to explain all facts of liberalization of trade. However, it provides two very powerful insights. One is that labour productivity differences are very important in explaining patterns in trade and the other one is that it is comparative advantage and not absolute advantage that is important for trade. In the Ricardian Model there is only one factor of production: labour. Therefore, comparative advantages only arise because of differences in labour productivity, which result from differences in technology. 2. Specialization from differences in endowments: Factor Proportion Theory (the Heckscher-Ohlin Model) In reality, in the real world, trade is not just determined by technological differences, but it also reflects differences in resources endowments across countries. Therefore, for example, Canada exports forestry products to the United States not because its workers are more efficient in forestry, but because Canada is more endowed with forests. To explain the importance of resources in trade two economists, Heckscher and Ohlin, have developed a theory where trade is determined by the interaction between the relative abundance of factors of production (such as capital, labour or land) and the relative intensity with which these factors of production are used in the production of different goods. Since in this theory, comparative advantages are determined by the proportion of factors endowments and the proportion in which these factors are used in the production of goods, the theory is known as the "factor proportion theory". Comparative advantage depends on countries’ relative endowment of factors of production According to the factor proportion theory, the country which is relatively abundant in labour will have a comparative advantage in the production of relatively labour intensive goods. The nation which is relatively capital abundant will have a comparative advantage in the production of the relatively capital intensive goods. In particular, for example, Country A has a comparative advantage in a capital intensive good relative to Country B, if its capital labour ratio is greater than in Country B. In a closed economy, the good that uses more intensively the relatively abundant factor will be cheaper If a country is capital abundant, then the cost of capital will tend to be relatively low. As a consequence, the cost of production of the capital intensive product, and its price, will tend to be relatively low. The opposite will occur in a labour abundant country – wages will tend to be relatively low and the cost of the labour intensive products will be relatively low. Differences in relative prices of the two goods will lead to trade. With trade: The prices of the traded goods will be the same across countries When countries start to trade, the prices of the two goods, the labour intensive good ( say, the agricultural) and the capital intensive good ( say, the manufacturing goods) will tend to be the same in the two countries. Therefore, for example, the price of the labour intensive good in the labour intensive country will tend to rise relative to the price of the capital intensive good. The labour intensive country will export the labour intensive good Both countries will produce more of the good, they have a comparative advantage for. They will tend to specialize. The capital abundant country will tend to specialize in the production of the capital intensive goods and export this product, while the labour abundant country will tend to specialize in the labour intensive good and export that product. Like in the case of the Ricardian Model, also in the H-O model, it is possible that the global production of both goods may increase with trade. It is therefore possible for both trading economies to consume more of both goods than in the absence of trade and therefore both countries gain from trade. 6 II. INCOME DISTRIBUTION EFFECTS Trade affects income disbribution There is, however, a very important difference between the results of the Ricardian Model and the results of Heckscher-Ohlin Model. In the Ricardian Model, labour is the only factor of production in the model, it is assumed that labour within each country can move freely without costs from one sector to another one. To the single individual, it does not make a difference whether he is employed in one sector or another one. This implies that a simple Ricardian model not only predicts that ALL countries gain from trade, but also within each country EVERY INDIVIDUAL is better off as a result of international trade. In the factor proportion theory, industries differ in the mix of the production factors they require. In the simplest case, there are two production factors: capital and labour and two sectors – one capital intensive and the other one labour intensive. The specialization in one of these two sectors, say the specialization in the production of the capital intensive good, increases the demand for one factor (capital in our example) while lowering demand for the other factor of production (labour). In the H-O model, it is not necessarily true that each individual in each country will gain from trade liberalization. Trade generates income redistribution effects, so that there will be groups who will gain and groups who will lose. Who gains and who loses? The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem Who will gain and who will lose? The Stolper-Samuelson Theorem helps us to identify winners and losers. Two economists, Stolper and Samuelson, showed that free trade raises the earnings of the country's relatively abundant factor and lowers the earnings of the relatively scarce factor. Let's consider the example of a capital abundant country: what will happen in this country after liberalization? In the capital abundant country, trade induces a reallocation of resources towards the capital intensive goods – therefore more capital will be demanded and this will increase the domestic price of capital. Owners of the capital will therefore gain more because returns to capital increase. What will happen to the demand of labour in this country? – This is the relatively scarce factor, where the country hasn't got a comparative advantage. The demand for labour will go down and wages will go down. To sum up, in the capital abundant country, owners of capital will gain and owners of labour will lose. In practice, there are costs to move from one sector to another one. Therefore, it is likely that resources employed in the import-competing sector suffer the consequences of a restriction shrinking of that sector. This explains why in industrialized countries at the moment where a labour intensive sector, like the textiles sector, is liberalized both capital owners and workers in that sector oppose free trade. The important result of the theory to bear in mind, though, is that despite income distribution effects, the country overall gains – that is gains outweigh losses. Costs of adjustment will be discussed in more detail later. II.A. TRADE BETWEEN SIMILAR COUNTRIES Similar countries trade similar goods: Intra-industry trade An important point to bear in mind is that the Ricardian Model and the Heckscher-Ohlin Model explain trade between different countries and different goods. In both models countries trade because they are different – they are either different in terms of their technological level or in terms of factor endowments. Countries specialize in the production of the good for which they have a comparative advantage and export that product. However, in reality most of the trade occurs between similar countries. And, between one quarter and one half 7 of world trade is intra-industry trade. That is trade between goods that fall in the same industrial classification. This is particularly true, if one considers trade among developed countries and in particular trade in manufacturing. In that case, intra-industry trade is most of the trade occurring. The Heckscher-Ohlin and the Ricardian Model do not explain intra-industry trade. Intra-industry trade relies on economies of scale In order to explain intra-industry trade, we need to introduce economies of scale. In many industries, the larger the scale of production, the more efficient the production. These industries are characterized by increasing returns to scale, or economies of scale. This implies that by doubling the input, like, for example, doubling the number of workers in the production of a certain good, the output is more than doubled. Consider, for example, a company that produces bicycles. And, suppose that the production of bicycles is characterized by economies of scale. This implies, for example, that if 10 workers, say, produce in a day five bicycles, then twenty workers will produce fifteen bicycles in the same time period. This is more than twice as much as 10 workers can produce. Gains from economies of scale Without Trade With Trade A B World A B World Video cameras 10 10 20 25 0 25 Bicycles 5 5 10 0 15 15 Now suppose, there are two countries: Country A and Country B, and two goods: video cameras and bicycles, for example. Suppose that both the production of video cameras and the production of bicycles are subject to economies of scale, so that doubling the number of workers employed in each sector, more than doubles the output of the sector. Suppose also that the two countries are identical, that is they have the same technologies and same endowment of resources. Assume also that labour is the only endowment. Initially Country A employs 10 workers in the video camera sector, and produces 10 video cameras, and employs 10 workers in the production of bicycles and produces 5 bicycles. Assume that the situation is identical in Country B – so that overall the world will produce 20 video cameras and 10 bicycles. Suppose now that all production of video cameras gets concentrated in Country A, while that of bicycles concentrates in Country B. Then, Country A will employ 20 workers in the production of video cameras and Country B will employ 20 workers in the production of bicycles. Because of economies of scales, the use of twice as many workers as before in the production of video cameras will more that double the output of video cameras produced in Country A. Suppose, for example, that the production of video cameras in Country A increases to 25. Similarly, suppose that in Country B, the production of bicycles will rise to 15, say. Of course, given that all workers have been moved to the other sector, no bicycles will be produced in Country A, and no video cameras will be produced in Country B. What happens to world production? Overall the world will gain. There will be 25 video cameras available and 15 bicycles available. Therefore, the potential exists for both countries to be better off with trade than without trade. 8 Gains from access to greater variety of goods and services It is possible to generalize this example and assume that each industry is characterized by a variety of goods. For instance, bicycles can be differentiated according to their style, colour, comfortableness of their seats, and so on. Similarly, one can differentiate video cameras in terms of their qualities, their memory power and so on. Trade liberalization may reduce the number of varieties produced by each country, but consumers gain access to a greater variety of goods overall In these circumstances trade allows each country to specialize in the production of a smaller range of goods than it would produce in the absence of trade. However, overall the consumers in each country will have available a wider choice of goods. This is because trade makes available to the consumer in each country, not only the varieties of the goods produced domestically, but also the varieties of goods produced in the other countries. Gains from trade in this case will arise from the access to a greater variety of goods and services produced worldwide. Countries will trade different varieties of the same good, thus leading to intraindustry trade. No income distribution effects An important result of the intra-industry trade theory is that intra-industry trade gives raise to very small income distribution effects. To the extent that trade is of an intra-industry type, trade will not create social problems of income distribution. Since intra-industry trade occurs mainly between similar countries, it follows that from a social point of view, it is easier to liberalize trade among similar countries than among different countries. This is because trade between different countries is mainly driven by comparative advantage and generates income distribution effects, thus hurting some groups. These groups may lobby against trade liberalization. Gains from faster innovation and technology transfer So far we have been looking at static gains from trade. There are also, however, dynamic gains from trade. Trade enhances the incentive to innovate through: Competitive effect - First of all, trade enhances the incentive to innovate. Innovation is the basis of economic growth. Therefore, through fostering innovation, trade may have positive effects on growth. Where does the incentive to innovate come from? – The incentive to innovate is determined by what in economics is called "competitive threat". That is, the difference between the profits that a firm would make if it innovates and the profits that it would make if another firm innovates first. Trade increases competition between countries, therefore it increases the losses a firm would face, if it fails to innovate, while a competitive firms does it. This, in turn, increases the competitive threat and the incentive to innovate. Scale effect - The second source of incentive to innovate is the scale effect. Trade, by enlarging the size of the market, increases the profits of a firm, if it innovates, thus increasing the incentive to innovate and invest in research and development. Trade favours technology transfer through various channels: A higher level of technology and productivity can also be due to the transfer of technology coming from abroad. Trade is one of the channels through which technology can be transferred across countries. 9 Reverse engineering - A simple example is reverse engineering. Trade makes available goods to a country. The mere fact of looking at a good, at its design, at its technology, allows competitors to capture in part the knowledge embodied in the good. To the extent that this knowledge is transferred to the importing country, the technology is transferred. Personal contacts - Technology is also transferred through personal contacts between importers and exporters. Enhanced foreign direct investment (FDI) - Or, technology can potentially be transferred through FDI. Trade also favours the inflow of foreign investments into the domestic country. The presence of a foreign company, technologically more advanced, may not only provide an incentive to existing domestic companies to update their technologies to remain competitive, but may also directly contribute to the transfer of technology through the training provided to local employees, or the quality standards required from local firms that supply inputs to the production process of the foreign firm or distribute its output. All this may trigger growth. II.B. ADJUSTMENT COSTS We have so far talked about gains from trade, but gains do not come without a cost. We have highlighted that gains from trade are the consequence of a reallocation of resources towards the relatively most efficient sectors. Specialization is the most important source of gains from trade. There are costs associated with this reallocation. These costs, generally referred to as "adjustment costs", are the costs incurred by displaced workers, those, for example, in the import-competing sector, that have to look for another job. Adjustment costs are also the costs of a firm that needs to invest in order to adjust to the new market conditions. Although these costs are unavoidable, as they are a direct consequence of the reallocation effect of trade liberalization, the size of these costs depends on a number of characteristics of the domestic market. Costs depend on: Functioning of credit market - The functioning of the credit markets and that of the labour market, for example, have important implications for the size of the adjustment costs. Clearly, if the credit markets works properly, displaced workers will find less difficulties in funding their periods of low income, or zero income. At the same time, firms would find more easily money for new investments. Functioning of the labour market - Similarly, the functioning of the labour market will determine the duration of unemployment for a worker who is moving to a different sector and looking for another job – the more efficient the labour market the more efficient will be the supply of information about vacancies, and more easily wages will adapt to the labour markets' conditions and more easily markets will tend to full employment. Quality of infrastructures and utilities - The quality of infrastructure and utilities is extremely important in some of the sectors where for example the cost of telecommunications has an important role. Credibility of the reform and quality of institutions - Important, is also the credibility of the firms and the quality of institutions: the more credible the reforms are, the more likely is that the market will react and respond quickly to the variations and a new equilibrium is reached faster. Since for developing countries credit markets, labour markets, quality of infrastructure are worse than for developed countries, the size of the adjustment costs may be more relevant for developing countries than developed countries. It is on the grounds of these higher adjustment costs that developing countries benefit from longer implementation periods in the arrangements for multilateral liberalization. 10 The role of national governments In general there are a number of policies the national government can put in place in order to minimize the size of these adjustment costs. Implement policies to minimize the size of the costs First of all, they can introduce policies to FACILITATE the adjustment. For example, they could supply information on the availability of jobs and allow more flexible wage setting regimes, or can provide credit guarantees during the adjustment phase. In addition, they can define an appropriate pace for the reform, they can underpin trade reforms by international commitments to increase the credibility of the reforms. Use export promotion schemes - Governments can also use export promotion schemes. The use of active export promotion by governments can be economically justified because of market failures. The adjustment process, in general, involves moving workers and capital from the shrinking import sector to the expanding export sector. The expansion of a new export activity, however, may require investments and investors may run into risks that are unknown or difficult to measure. If financial markets are not sufficiently developed or if they are inefficient, it may prove to be difficult for the exporter to get a loan, or hedge for these risks. Under these circumstances, the inefficiency of the credit market would be an obstacle to the expansion of the exporting sector, and an obstacle to the process of adjustment. Therefore, there is a rationale for the government to put in place export promotion policies to facilitate the adjustment process. Implement policies to compensate those who lose Supplying social safety nets - The second set of policies that the government could put in place to favour the adjustments process and, in so doing, lower the adjustment costs, is compensation policies for those groups that lose out as a consequence of liberalization. For example, the governments could identify those individuals or those groups that face adjustment costs and, for example, supply social safety nets during the transition period to alleviate their suffering. Appropriate redistributive tax system For long term losses, national governments can develop an appropriate redistributive tax system that compensates individuals for their losses. 11 III. TRADE POLICY AND DEVELOPMENT So far, we have been looking at why countries trade, what determines the patterns of trade, and what are the gains and the costs associated with trade liberalization. These are certainly interesting questions, but what is more interesting to understand is what should a trade policy of a country be, in order to foster development. Trade liberalization and development Development is a complex concept – it is a process in which people through their work – investing and trading with other countries are able to secure their basic needs – education, health, comfortable living standards and freedom. In order to obtain all this, people need adequate economic forces. Therefore an adequate level of income is a basis for all this. Now we have seen that trade liberalization can help countries to better utilize their resources through specialization and through the exploitation of economies of scale. Trade also fosters the incentive for innovation and the diffusion of technologies. It is a more efficient use of resources that provides the potential for a higher level of income and therefore a higher level of development. There is a generally positive relationship between openness and income and the general picture is that open and export oriented countries have succeeded in their development efforts, while heavily protected and inwardlooking countries have not. Protectionist policies have been used as well to “favour” development However, often a number of protectionist policies have been used as well to favour development. We will now turn to the analysis of how protectionist policies work – what are the instruments for protection – what are their effects and what is the rationale behind protectionist policies. Moreover we will discuss some of the evidence of the results of these policies. III.A. WHAT ARE THE INSTRUMENTS OF TRADE POLICY? Tariffs What are the instruments of trade policy? The most well known one is clearly the tariffs. Tariffs can be specific tariffs or ad valorem tariffs. A specific tariff is a charge – a fixed charge for each unit of the imported good. While an ad valorem tariff is a percentage tax on the value of the imported good. Quotas The best known form of non-tariff barrier is a quota. This is the maximum quantity of some good that may be imported. Export subsidies Export subsidies also represent an instrument of trade policy, as governments by providing support to the export activity distort trade. Any other policy-induced trade cost In general, any policy-induced trade cost represents a barrier to trade. For example, non-tariff barriers may be a particular type of standard that increases relative costs of production for foreigner producers. Or, particularly 12 time consuming customs clearance procedures that increase overall transport costs. High transport costs due to anti-competitive behaviours or the low quality of infrastructure may also be thought of as barriers to trade. In all these cases the analysis of the impact of trade barriers are quite similar. For simplicity, in the rest of the analysis we will look at the impact of import tariffs. But, please bear in mind that the same comments are applicable to all other forms of barriers to trade. III.B. WHAT IS THE IMPACT OF AN IMPORT TARIFF? Let's focus for simplicity on the impact of an import tariff on a certain economy, and let's consider initially the case of a small country, where by small country we mean the case of a country that cannot affect the world price of the imported good. Case of a small country Suppose initially that there are no tariffs. Then, consumers in this country pay the world price to consume. Suppose that the government decides to levy a tariff on the imports of rice, for example. The imposition of a tariff will, first of all, increase the domestic price of the imported good. People who want to consume rice will now have to pay the world price plus the tariff. Domestic consumers of rice will, therefore, be worse off, as they will have to pay more, if they want to consume the same quantity of rice as before. On the other hand domestic producers of rice will gain, because they will be able to sell rice at a higher price. And the government will also gain, as it will be able to collect tariff revenue. Overall, in the case of a small country, international trade theory shows that the country as a whole will lose and national welfare will be reduced by the imposition of a tariff. Case of a large country Different is the case of a large country. Notice that here, by large country we do not mean a country that is large in terms of its geographical size, but rather a country whose import demand for a certain good is so large that it can affect the world price of the imported good. What happens if a large country imposes a tariff on the import of a good, let's say rice? Like in the case of a small country, first of all, the domestic price for rice will increase. This will reduce the demand for imports of rice. But, now, in the case of a large country, the lower demand for imports will lead to a reduction in the world price of rice. In other words, by imposing a tariff on an imported good, a large country is able to affect the price of the good to its own advantage! Economists refer to this gain as "terms of trade gain" (TOT gain). This gain stems precisely from the ability of the country to affect the world price of the imported good. It is because of the possibility of terms-of-trade gain that in the case of a large country the impact of the imposition of a tariff on national welfare of a country is ambiguous, i.e., it can be eithr positive or negative. What is important to highlight at this stage is that terms-of-trade effects only occur in the case of a large country. In the case of a small country, the imposition of a tariff is unambiguously welfare decreasing! 13 III.C. WHY DO GOVERNMENTS IMPOSE IMPORT TARIFFS? International trade theory clearly asserts the benefits of free trade and highlights the inefficiency losses of imposing a tariff. In reality, very few countries have adopted total free trade. An exception is probably the one of Hong Kong. There are various reasons for this. The political economy justification Often it is a question of political economy. Saying that there is a political economy justification behind the imposition of a tariff means that protectionist policies are the consequence of the lobbying activity of industries in the import-competing sectors that wish to be protected against competition from the rest of the world. There are also some theoretical arguments that can justify the use of protection from a national welfare point of view. Economic arguments for protection: 1. Terms-of-Trade argument The first argument that we will look at is the terms-of-trade argument, according to which there is an optimal level of tariff at which national welfare is maximized. 2. Infant industry argument The second argument, we will look at, is the infant industry argument for protection. According to this theory, there are circumstances where an industry may need temporary protection in order for the country to develop a comparative advantage in that sector. 3. Strategic trade policy The third argument for protection is the strategic trade theory argument. There might be circumstances where a subsidy to a domestic firm may deter foreign companies from entering into the market and competing with the domestic firm. In this case, the domestic firm will benefit from monopoly profits and the country overall may gain. 4. Other arguments The other argumens for propection rely on the fact that import tariffs are a tool to raise government fiscal revenue or they are a tool to redistribute income from the export sector to the protected sector. Let's now look at each of these arguments in turn. III.C.1. THE TERMS-OF-TRADE ARGUMENTS FOR PROTECTION Theory The terms-of-trade arguments follows directly from the cost and benefit analysis of the imposition of a tariff. We have seen before, that when a large country introduces a tariff, there may be positive terms-of-trade effects. The tariff reduces the demand for imports and this, in turn, decreases the world price of the imported 14 good. Economic theory shows that there is an optimal tariff rate that is positive, for which the terms-of-trade gains must offset distortionary effects of the imposition of a tariff. BUT Although theoretically valid, this argument presents very strong limitations, when applied to actual policy making. First of all, the argument is valid only for the case of large countries. Small countries are not able to affect foreign prices, therefore they cannot benefit from terms-of-trade gains. Second, even in the case of a large country, a trade policy that relies on terms-of-trade gains is a beggar-thyneighbour policy. This is because the gains to the large country come at the cost of welfare losses in the foreign exporting countries that will receive a lower price for their exports. A retaliation of foreign exporting countries may start a trade war that would leave all countries worse off. III.C.2. INFANT INDUSTRY ARGUMENT FOR PROTECTION The infant industry argument for protection relies on the arguments that temporary protection might be needed for a country to develop a comparative advantage in a particular sector when markets fail. For example, if there are inefficiencies in the financial market, it may happen that an entrepreneur that wants to start a new business will not find the appropriate funding for his or her activity, even if the activity is profitable. Inefficiencies in financial markets in developing countries, for example, may stop resources from moving from the traditional agricultural sectors to new manufacturing sectors. The simple reason might be that banks are too small, their portfolios are not sufficiently diversified, or they lack information, and consequently they cannot manage the risk connected with an investment in a new sector. Evidence Historically, many developing countries, in the aftermath of the Second World War, have adopted an importsubstitution strategy in the attempt to develop their manufacturing sector. In many developing countries, the evidence has been that although the protected sector did develop, the production stagnated for a long time and the sector needed continued government intervention to stay in the market. In other words, importsubstitution strategies did not lead to the development of a competitive industry that eventually could face its competition in the international market. That is to say that import-substitution strategies did not allow the development of the comparative advantages they were meant to develop. A result that supports a very strong argument against infant industry protection is that it is very difficult for governments to identify industries of potential comparative advantage! III.C.3. STRATEGIC TRADE POLICY ARGUMENT Let's now turn to the discussion on the strategic trade argument for protection. Some markets may be characterized by imperfect competition so that there are only a few big players and excess profits are made Some markets are characterized by imperfect competition. It may occur that because of high fixed costs, only a few companies can survive in a market and these companies are able to realize above normal profits. Countries may decide to enter in competition to try to capture these excessive profits. Let's take, for example, the case of the air transport industry. It might be the case that, on specific routes, only one company can 15 survive: If two companies (a domestic and a foreign company, for example) were in the market, they would both realize losses; but if one company survives, it will realize monopolistic profits. A subsidy by government to a domestic firm can deter foreign company and raise the profits of the domestic company by more than the subsidy In these circumstances if the government of one country provides its domestic air transport company with a sufficiently large subsidy, it may create for the company the incentive to enter in the market independently of whether the foreign company enters or not in the market. On the other hand, the foreign air-transport company, facing the competition of a subsidised company, will decide not to enter in the market, because if it did, it would certainly realize losses. In the end, only the subsidized company will stay in the market, and it will realize monopolistic profits. To the extent that these profits are higher than the subsidy paid by the government, the overall welfare of the country that has subsidized its domestic industry will increase. Is this policy desirable? At first sight, it might look quite a good idea, under these circumstances, to protect the domestic industry and capture foreign profits. However, the desirability of such a policy depends on a number of specific conditions. Firstly, it is necessary that the subsidy is sufficiently large to actually deter the foreign firm from entering in the market. If it didn't and both companies entered in the market, then the profits captured by the domestic firm may not cover the cost of the subsidy and the country as a whole will be worse off. In addition, a strategic trade policy is a beggar-thy-neighbour policy, because it is based on the assumption of capturing foreign profits. As a consequence, strategic trade policy is subject to retaliation and therefore entails the risk of a trade war that might leave everybody worse off. III.C.4. OTHER ARGUMENT FOR PROTECTION Fiscal revenue argument Among other arguments for protection, there is that of fiscal revenue. In many countries, especially developing countries, income taxes are difficult to collect, while tariffs are easier to collect: imported goods have to cross a border and therefore it is more difficult to hide them. Countries, especially developing countries, have often used this argument to keep their tariffs high. There is evidence, however, that in many countries the simplification of the tax and tariff systems has led to an increase in the overall fiscal revenue, even when accompanied by a reduction in the average tariff rate. This is because a simplified system is easier to control, people understand it better and therefore it is less prone to evasion. Income distribution Finally, some countries have used protection as an instrument to redistribute income. We have said that liberalization redistributes incomes. Trade liberalization increases the returns of the relatively abundant factor and reduces the returns of the scarce factor. Maintaining protection is therefore a way to avoid these adjustments. This is obviously true. However, trade policy is not the only instrument to achieve redistributive goals. And economists argue that it is more efficient to use fiscal policies than trade policy to achieve income redistribution targets. 16 IV. NEED OF A MULTILATERAL COMMITMENT IV.A. IS THERE A REASON FOR COMMITTING TO MULTILATERAL LIBERALIZATON? Trade liberalization leadS to gains also when it is unilateral. Yet, historically it has been achieved through international negotiations It is interesting to notice that historically tariffs were not reduced through a number of unilateral decisions by individual countries, but rather through a number of rounds of international negotiations. But, if countries can realize gains from trade by liberalizing unilaterally, why do they engage in international negotiations and liberalize trade within a context of multilateral commitments? Theoretical reasons for coordinating liberalisation with others There are at least three reasons why it is easier to remove tariffs at a multilateral level. 1. Reciprocal exchange of market access allows governments to mobilize export lobbies to counter-balance import competing lobbies First of all, we have seen that when a country liberalizes trade, some people gain and others lose. We have seen, in particular, that the import competing sector is likely to lose from opening up to trade, while the export sector is likely to gain. If a country liberalizes unilaterally, it is likely to face the pressures of the importcompeting sector that will mobilize and lobby against liberalization. On the contrary, if a country is able to negotiate international liberalization, it will be able to counteract the pressure of the lobbies of the importcompeting sector by mobilizing the exporters' lobbies to counterbalance the lobbies of the import-competing sector. From a political economy point of view, it is much easier for a country to reduce tariffs if its trading partners are doing the same. 2. International commitments avoid tit-for-tat trade restrictions Another important reason why it is easier to reduce tariffs at the multilateral level is that by coordinating liberalization with other countries, countries are able to avoid trade wars. If each country set its trade policy independently, then the optimal policy for large countries would be to set the "optimal tariff". Since this is beggar-thy-neighbour policy, it is subject to retaliations by other countries. To avoid tit-for-tat trade restrictions, the best option is to cooperate to jointly liberalize trade. 3. Enhances credibility of a trade policy and avoid time inconsistency problems There is also a third important reason for underpinning a trade policy to a multilateral commitment that is that a multilateral commitment enhances the credibility of a trade policy itself and helps to avoid time inconsistency problems. 17 IV.A.1. TIME INCONSISTENCY Let's explain what time inconsistency means with an example. Example: Interaction with financial sector Suppose that a government wants to liberalize its financial sector. Suppose also that national banks are inefficient and have accumulated non-performing credits. So they are in a very critical situation. Assume that, at a certain point in time, the government announces that one year later, it will open up the financial sector to foreign competition. What will banks do? There are two possibilities: If the national banks believe the announcement, they will start to adjust their bad credits and try somehow to become more efficient. However, if they don't believe the announcement, they will not adjust. In this case, one year later, if the government does liberalize the financial sector, there will be a financial crisis in the country. Therefore, if banks do not adjust after the announcement, probably the government will not be implementing the policy one year later. Time inconsistency occurs when the announcement at time 2 is no longer an optimal policy at time 4. Aware of time inconsistency problems, banks will decide not to adjust. Time inconsistency occurs when the announcement, made at a certain time, is no longer an optimal policy, at the time when it should be implemented. Aware of time inconsistency problems, banks will decide not to adjust after the announcement of the government. As a consequence, when the time of implementing the policy arrives, the government will be obliged not to liberalize, otherwise it would risk a complete crisis in the financial sector. International commitments solve the time inconsistency problems The time inconsistency problem can be solved through international commitments. International commitments will give credibility to the government announcement that it will liberalize the financial sector, and banks will adjust. IV.A.2. OTHER REASONS FOR MULTILATERAL LIBERALIZATION There are other reasons in favour of multilateral liberalization. One of these is to avoid the risk of trade diversion due to the formation of regional trade agreements. No risk of suffering from trade diverting effects of regional trade agreements The policies we have described so far are non-discriminatory policies. This means that if two countries decide to reduce their reciprocal tariffs, they will also apply these lower tariffs to the rest of the world. It may happen as well that countries reduce their tariffs in a preferential way. This means that a set of countries liberalize their intra-regional trade, but they keep their barriers against the rest of the world. At the first sight, this might seem a good policy. We have said that unilateral liberalization is good. We have said that multilateral liberalization is good, so one may think that preferential liberalization should also be good. In contrast, when countries liberalize in a preferential way, they may incur the risk of suffering from the consequences of what economists call "trade diversion". Trade diversion occurs when the imports from a trading partner of the regional agreement replaces imports from the rest of the world, although the trading partner is not the globally most efficient producer of the good. Trade diversion has clearly negative effects on the exporting countries outside the preferential area. What are the consequences for the importing country member of the preferential area? On the one hand, consumers gain, because they pay less to import the good from a regional partner, 18 since there are no import tariffs. On the other hand, the government loses tariff revenue. Since the trading partner is not the most efficient producer of the good, this loss may be larger than the gain to consumers. In other words, trade diversion may also have negative effects on the welfare of the partners to the preferential agreement. Transparency and predictability Another advantage of committing liberalization to international agreements is that of enhancing the transparency and predictability of conditions for the exchange of goods and services. For example, this reduces the costs of getting information on the tariff rates applied on a certain product by a certain country to another one and put countries on a level playing field. 19 V. CONCLUSIONS Let's now in our conclusion briefly summarize the results of this presentation. I think that this presentation provides four main messages. The theory of international trade suggests that the optimal trade policy regime is one of free trade or a regime with low and even protection The first one is that the optimal trade policy regime is either one of free trade or a regime with low and even protection. We have said and shown that the regime of low protection may be justifiable only in the case of a large country. While various reasons have been advanced why countries have to depart from this prescription (infant industry or strategic trade policy), there is little evidence that these policies have resulted in demonstrably better economic performance The second important lesson is that while various reasons have been advanced, why countries have to depart from this prescription (such as the infant industry argument or the strategic trade policy argument), there is little evidence that these policies resulted in demonstrably better economic performance. On the contrary what we have seen is that, in general, sectors that have been protected in the initial stage of their development, then have continued to be protected and have never grown into competitive sectors. While unilateral liberalization is good, multilateral liberalization leads to larger gains A very important lesson is that while unilateral liberalization is good, multilateral liberalization not only leads to larger gains, but it also politically more sustainable and more credible. Trade policy is only one part of a much bigger growth/development story Finally, the fourth lesson is that trade is only one part of the growth and development story. Trade liberalization may not have the desired effect if markets are not functioning well or if institutions are weak. 20 Frequently Asked Questions Question 1: Why do countries trade? Answer: Countries trade because they are different. They have different technologies or have a different amount of capital and labour. Or they trade because they produce different varieties of the same good. In the first case trade generates gains because it allows countries to specialize in the production of the good it can produce relatively more efficiently or that it uses intensively the factor that they are more endowed with. In the second case trade generates gains because people love variety and trade provides access to different varieties of goods produced all over the world. By increasing the variety of goods consumers can access and buy, trade makes consumers better off. Question 2: One of the main results of international trade theory is that trade is beneficial for all countries – why? Answer: Let's consider for simplicity reasons, the case when countries differ in their level of technology. International trade theory tells us that trade allows countries to specialize in the production of the good they can produce relatively more efficiently. When countries concentrate their resources in the production of this good, overall global production will go up, and consumers will be able to consume an amount of goods greater than they would have been able to consume without trade. Question 3: What determines the pattern of trade? Answer: When trading partners are different, each country will export the product in which it has a comparative advantage. So, for example, in a case where countries differ in their level of technology, each country will export the product that it can produce relatively more efficiently. When trade occurs between similar countries, countries will tend to trade different varieties of the same good. In this case, the theory of international trade cannot tell us anything about the pattern of trade. The pattern of trade is random. The only thing international trade theory can predict is the volume of trade between the countries. Question 4: Can a country have a comparative advantage in all goods? Answer: A country can have an absolute advantage in all goods. That is, it can have a better level of technology in the production of each good in the market. But, it cannot have a comparative advantage in all goods. There will always be a good in which its trading partner has a comparative disadvantage. Question 5: Does the fact that trade is mutually-beneficial imply that all individuals in each country are better off? Answer: No. An important insight of international trade theory is that international trade, although benefiting the country as a whole, has income distribution effects. This means that some groups will gain, while other groups 21 may be hurt from trade liberalization. In particular, those individuals and capital employed in the import- competing sector will suffer losses, while those employed in the export- competing sector will realize gains. Question 6: What policies can a government implement to face the adjustment problems connected with trade liberalization? Answer: The reallocation from the import competing sector to the exporting sector induces costs. These costs are represented, for example, by the cost of workers to look for another job in a different sector. There are not only simply searching costs, but there might be costs related to the fact that workers might need some training to learn to work for another firm or company in another sector. The government can intervene in this process by facilitating this adjustment process. The government may, for example, supply information on job vacancies, thus reducing search costs. It may provide credits by allowing workers, poor workers who need time to look for another job, to borrow money from a bank while looking for another job. It may provide contributions for training. The government may as well define an appropriate pace for the reform. It may implement reforms slowly, so that a small number of workers that look for a different job enter into the market at each phase of the implementation period, thus limiting negative social consequence. The government may also use export promotion schemes. That would allow a more rapid expansion of the exporting sector and facilitate the adjustment. Alternatively, the government may implement policies to compensate those who lose from trade liberalization. This can be done by offering during transition periods, for example, social safety nets to support the workers who have lost their jobs – or by implementing appropriate redistributive tax system, that may compensate for long term losses. Finally, underpinning trade reforms to international commitments can also be a way to facilitate the adjustment process. This is because, by committing internationally, the government increases the credibility of the reforms and this is likely to trigger the adjustment process even before the implementation period of reforms. Question 7: What are the effects of a tariff? Answer: The imposition of a tariff increases the domestic price of an imported good. As a consequence, consumers will demand less of that good in the domestic country, and imports will fall. In this case there are two possibilities: One is that the reduction in the demand of imports also decreases the world price of the imported good. This is the case of a large country, where the country realizes the so called terms-of-trade gains. The second case is that of a small country, where, despite the reduction of the demand for imports, the world price remains fix and there are no terms-of-trade gains. The difference between the two cases is very important, because in the case when a country can realize termsof-trade gains, trade theory shows that, for a sufficiently low level of tariffs, the imposition of a tariff may increase the overall welfare of the country. In contrast, in the case of a SMALL country, that is a country that is not able to affect the world price through changes in the demand for imports, there are no chances that the tariffs may increase the welfare through terms-of- trade gains. In the case of a small country, the imposition of a tariff unambiguously generates a loss. What generates this loss is the fact that the higher domestic price reduces consumers' welfare, as consumers will have to pay more to consume the same amount of their preferred good. 22 Question 8: What are the risks associated with the adoption of an "optimal tariff"? Answer: A country may justify its protectionist policy on the grounds of terms-of-trade gains. Optimal tariff theory says that there is a small tariff at which the welfare of a country can be maximized. That is to say that there is therefore an optimal tariff for which terms-of-trade gains offset losses. There are, however, a number of problems associated with this policy. First of all, it is important to define exactly what a sufficiently low level of tariff is. And that from an empirical point of view is not very easy to determine. Second, it is important to realize that the argument is only valid for a large country. And, this does not mean that the country needs to be big, but it means that the country is able to affect the world price of the commodity on which it imposes the tariff. There is also another problem, more serious, that is that the termsof-trade argument for protection is a beggar-thy-neighbour policy. terms-of-trade, but the rest of the world loses. By imposing a tariff, a country gains in Therefore it is likely that this policy will be subject to retaliation. And, this may start a trade war that makes everybody worse off. Question 9: What do we mean by infant industry argument? Answer: Many governments have used the infant industry argument to protect their manufacturing sector. The argument is that the country may have a potential comparative advantage in the manufacturing sector, say, but that the industry is too young and too little developed to compete at the international level. For this reason, the industry is given a "temporary" protection: to allow the industry to develop, in a way that, as the technological level of the industry increases, the comparative advantage builds up, and the country may, eventually, open up to international competition. The reason why the manufacturing sector does not naturally develop, or better the reason why the industry is "infant" is a market failure. For example, there is an inefficiency in the financial market that impedes the natural forces of the market to operate. Although at first sight reasonable, this theory is not without drawbacks. First of all, it is difficult for the government to identify which industry has a potential comparative advantage. If inefficiencies in the financial markets do not allow banks, for example, to provide funding to potentially growing sectors, it is equally difficult for the government to identify which sector is the one with the highest potential for growth. Over time different sectors have shown different potential for growth and it is not necessarily true, from a development point of view, that targeting sectors with higher value added is beneficial. A sector with higher value added may present a very small proportion of the production of a country and growth in that sector may not mean a lot in terms of the country's development, while a growth (even a low rate of growth) in a sector that represents a larger share of the production of the country may have a significant effect on development. Another point to make is that is that import-substitution policies are not the most efficient instrument to address a market failure. To continue with the same example as before, if the reason why a certain industry does not develop is an inefficiency in the financial market, it will be more appropriate to address directly this issue rather than using trade policy to protect the manufacturing sector. Question 10: What is the evidence of the effectiveness of infant industry policies? Answer: What happened, in many countries, is that industries that have been protected from import competition did develop, but they have never been competitive in the international market. The country has not developed a comparative advantage in the protected sector, and firms in that sector have continued to request government intervention to stay in the market. 23 Question 11: Is it desirable to support an industry to beat foreign competition? Answer: Governments may be pushed to subsidize some industries for strategic considerations. In a sector characterized by few big players, it may happen that a subsidy gives a strategic competitive advantage to the domestic firm, thus pushing the foreign competitor out of the market, and increasing the domestic firm's profits above the level of the subsidy. This extra profits might compensate the country for the cost of the subsidy. However, in the real world, the implementation of such a policy may be quite risky and difficult. First of all, it is important that the subsidy actually deters the foreign firms from entering. If this does not happen, the extra profits of the subsidized firm may not be sufficient to compensate the government for the cost of the subsidy. Secondly, even in the case when the foreign firms are actually pushed out of the market from the subsidised firm, it is necessary that the extra profits of the domestic firm be greater than the subsidy, for the strategic policy to be welfare enhancing. To be able to calculate this in advance requires a lot of information, difficult to obtain and subject to uncertainty. Finally, strategic trade policies make foreign countries worse off. This implies that the domestic country may face a retaliation policy on the part of foreign countries, in which case both the domestic country and the foreign countries will be worse off. Question 12: Why do countries commit their trade policy to multilateral liberalization? Or, in other words, why do countries join the WTO? Answer: Tying up a country's trade policy to international commitments has a number of advantages. First of all, international commitments enhance the credibility of the trade policy and this avoids problems, such as time inconsistency problems, whereby a trade policy announced today does not trigger the necessary adjustments to make it an optimal policy also at the time of implementation. For example, if a government announces to liberalize the financial sector in a country where banks are highly indebted and banks do not adjust their bad debts, at the time of the implementation, if a government did implement the policy, the financial sector would go bust. Therefore, it is very likely that the government will not to implement the policy. The second reason for liberalizing at the multilateral level is a political economy reason. When a country liberalizes at the multilateral level, at the same time, it reduces its import tariff and accesses more freely the markets of other countries. In this way, at the domestic level, governments can counterbalance the lobbying pressure of the import-competing sector against liberalization, by mobilizing the export lobbies that will benefit from the higher market access in foreign markets. Thirdly, international commitments avoid tit-for-tat trade restrictions that make all countries worse off. If countries (large countries, say) did not coordinate their liberalization, they would choose to set the optimal tariff, and by doing so, they will inflict upon each other terms-of-trade losses. worldwide. This would generate losses Coordination among countries pushes them towards free trade and this generates gains for all countries. 24 Question 13: We have said that unilateral liberalization is good. We have also said that multilateral liberalization might be better. Does it follow that joining a preferential trade agreement will always make a country better off? Answer: Suppose that there are three countries that make up the world. Countries A, B and C. Suppose as well that Country A signs a free trade agreement with Country B and therefore reduces its import tariff on textiles, let's say, against country B. Suppose as well that Country B is not the most efficient producer of textiles, while Country C is. Before the formation of the free trade area, Country A was importing its textiles from Country C. After the FTA, Country B will be able to export to Country A at a cheaper price than Country C despite not being the most efficient producer. It is clear that Country C will loose following the formation of a free trade agreement between Country A and Country B because trade will be diverted from Country C to Country B and Country C will no longer export textile to Country A. Will Country A unambiguously gain from this free trade agreement? The conclusion is not that obvious. On the one hand, because of the reduction of the import tariffs, consumers of textiles in country A will gain because they will now pay less for their textiles. On the other hand, the tariff revenue of the government will go down, as the country now imports textiles from Country B duty free. The overall effects of liberalizing trade preferentially with Country B is ambiguous. In particular, economic theory shows that Country A will be more likely to lose, the higher the efficiency gap between Country B and Country C in producing textiles and the higher the external tariff toward country C. 25