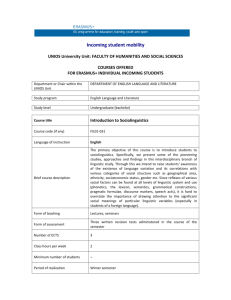

Sociolinguistics Lecture 2

advertisement

Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali “Everyone knows that language is variable.” Sapir (1921: 147) Recapitulation Register (field, tenor and mode) Dialect: Regional Dialect &Social Dialect (Trudgill 1975) Types of Variation: Regional, Social, Personal and Temporal Speech Communities and Language Communities Speech Community: A set of people with a common language, or who share a repertoire of varieties (accents, styles, even languages in multilingualism); people who live together and interact through language; people with shared social attributes (young people, lawyers, women); people in the same social system. Standard Language and ‘Correctness’ Prescriptivism and Descriptivism in Language Study Views of Society Traditionally, sociologists study societies in terms of categories like class, ethnicity or regional and economic characteristics. Functionalism A system made up of functioning parts. To understand any part of society (for example the family or school), the part must be examined in relation to the society as a whole. The social system has certain basic needs (or functional prerequisites) which must be met if it is to survive (for example, food and shelter). The function of any part of society is its contribution to the maintenance of the overall whole. Marxism Conflict is a common and persistent feature of society, not just a temporary disturbance of the social order. Karl Marx (1818–83) stressed the economic basis of human organization, which could be divided into two levels: a base (or infrastructure) and a superstructure. Class denotes a social group whose members share a similar relationship to the means of production. Essentially, in capitalist societies there is the ruling class which owns the means of 1 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali production (e.g. land, raw materials) and the working class which must sell its labour power to earn a living. Concepts, Indicators & Variables Variable is a concept that varies. Measurability is the main difference between a concept and a variable. Concepts stand for phenomenon not the phenomenon itself. The concept ‘Richness’ can easily be converted into indicators and then variables. An attribute is a specific value on a variable. For instance, the variable sex or gender has two attributes: male and female. Types of Variables Independent variable is the cause supposed to be responsible for bringing about change/s in a phenomenon or situation. Dependent variable is the outcome of the change/s brought about by changes in an independent variable Extraneous variables are the several others factors operating in real-life situation may affect changes attributed to independent variables. Linguistic Variation Dialectical Variation Free Variation Weinreich, Labov and Herzog (1968) called 'orderly heterogeneity' - structured variation. This 'structure' is manifested in a number of ways, most notably in the regular patterns found when sociolinguists correlate social structure with linguistic structure. Example: The correlation of the absence of third person present tense marking (e.g. 'she play', 'the boy sing') with social class membership in the city of Norwich in England (Trudgill 1974) - the 'higher' the social class of the speaker, the lower the absence of -s marking 2 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali Linguistic Variable William Labov (e.g. 1972) devised the notion of the linguistic variable to help capture this idea of quantitative difference. A linguistic variable is a set of related dialect forms all of which mean the same thing and which correlate with some social grouping in the speech community. Variables are written in parentheses and variants in brackets Similar meaning should not refer only to the semantic meaning of the variable; rather it should consider the social meaning as well. Types of Linguistic Variables Markers are those variables like (r) and (th), which show stratification according to style and social class. All members react to them in a more or less uniform manner. Indicators, show differentiation by age or social group without being subject to style-shifting, and have little evaluative force in subjective-reaction tests. Only a linguistically trained observer is aware of indicators. As difference in ‘God’ and ‘Guard’ Stereotypes are forms that are socially marked – that is, they are prominent in the linguistic awareness of speech communities, as in the case of ‘h-dropping’ in Cockney. Linguistic Variables and Linguistic Levels A difference of a few percent in usage can lead to the association of a particular linguistic form with a particular social group. Correlation and Linguistic Variation The types of external variables that correlate with the relative frequency of fluctuating variants may include traditional demographic variables (e.g. age, social class, region), constructed social groupings and practices of various types (e.g. communities of practice, social networks), interactional dynamics (e.g. power relations, solidarity), and even personal presentation styles and registers (e.g. performance, mimicking). Objective of Variationsit Sociolinguistics The relationship between social factors and the use of dialect variants should be explored, to demonstrate that variability is not haphazard, but structured and motivated. The relationship 3 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali between language variation and language change should be made clear, along with the pivotal role in sociolinguistic variation studies of the apparent time method for detecting ongoing change Studies in Linguistic Variation Regional Dialects: Rural Dialectology General Methodology for studying Regional Dialects Pilot study for the Linguistic variables Identification of the localities Questionnaires based on Linguistic variables Fieldwork Linguistic Maps Linguistic Survey of India George Grierson, a British magistrate resident in India for half a century and a trained Sanskritist and philologist, provided a classification of the languages of India (from 1894 onwards). He had been hired by the government of India to undertake a survey of north and central India, then containing 224 million people. Grierson used local government officials (district officers and their assistants) in different localities to write down specimens from suitable consultants in the local script and in Roman characters. On the basis of degrees of similarity across villages, Grierson grouped village speech into dialects and then dialects into languages. He posited the existence of 179 languages and 544 component dialects of these languages. Grierson’s classification of north Indian languages based on the presence or absence of an /l/ in the past participle. Thus the words for ‘beaten’ in languages are as follows: Assamese maˉ r-il, Bengali maˉ r-ila, Bihari maˉ r-al, Oriya and Marathi maˉ r-ilaˉ , Gujarati maˉ r-el, Sindhi maˉryalu. On the other hand Hindi, which does not belong to this outer ring of north Indian languages, has mar-a. Linguistic Survey in Germany Wenker carried out his investigation by post, contacting every village in Germany that had a school. His questionnaire comprised forty sentences having features of linguistic interest, which the local headmaster/teacher was asked to rephrase in the local dialect. ‘In winter the dry leaves fly around through the air’. 4 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali Over 45,000 questionnaires were completed and returned Linguistic Survey in France Gillieron used on-the-spot investigation, rather than a postal survey. He employed a single fieldworker, Edmond Edmont. Gillieron bought Edmont a bicycle, and sent him pedalling off around 639 rural localities in France and the French-speaking parts of Belgium, Switzerland and Italy’. He chose one consultant per locality (occasionally two), usually a male aged between 15 and 85 years. Drawing and Interpreting Dialect Maps Concentric (or near-concentric) isoglosses show a pattern involving the spread of linguistic features from a centre of prestige (usually a city or town) Wave Theory: linguistic innovations spread in wavelike fashion Peter Trudgill (1983a: 170–2) has suggested that the spread of innovations in modern societies occurs in other ways too. Certain sounds ‘hop’ from one influential urban centre to another, and only later spread outwards to the neighbouring rural areas, including the areas between the two centres. (Transition area) Criticisms of Traditional Dialectology The type of people interviewed (NORM) The narrow choice of informants Focus of the traditional surveys fell on bits of language. The extreme length of the questionnaires Fieldworkers’ judgments of vowel quality Segmental features Social Dialects: Urban Dialectology David Britain’s study of Fens David Britain (1997) has studied the border dialect area known as the Fens in England, a marshy area about 75 miles north of London and 50 miles west of Norwich. At one time, the sparse population lived on a few islands of higher ground. Only after the seventeenth century when the marshes were drained did the Fens become fertile, arable land attracting greater human habitation. One of the features studied by Britain was the variation between east and west with respect to the diphthong [ai] (i.e. the vowel sound in the lexical set price, white, right). The eastern Fens have a 5 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali centralised [əi], while the western Fens have [ai]. Britain describes an interesting compromise in central Fens, the part more recently opened to habitation. Here both pronunciations are found, but in a special pattern, determined by what kind of sound they are followed by. The centralised [əi] pronunciation occurs before voiceless consonants (like p, t, k, f, s), while [ai] occurs in other phonetic environments, namely before voiced consonants (like b, d, g, v, z) and before vowels. Britain argues that such ‘fudging’ occurred when newcomers tried to assimilate to the norms of more settled communities which were themselves divided in terms of pronunciation. John Fischer’s study John Fischer had discussed the social implications of the use of -in versus -ing (e.g. whether one said fishin’ or fishing) in a village in New England in 1958. Fischer noted that both forms of the present participle, -in and -ing, were being used by twenty-one of the twenty-four children he observed. Rather than dismissing it as random or free variation of little interest to linguists, Fischer tried to correlate the use of the one form over the other with specific characteristics of the children or of the speech situation. Fischer (1958: 51) concluded: ‘the choice between the -ing and the -in variants appear to be related to sex, class, personality (aggressive/cooperative), and mood (tense/relaxed) of the speaker, to the formality of the conversation and to the specific verb spoken’. Labov’s Martha’s Vineyard The island of Martha’s Vineyard off the New England coast was the setting of Labov’s study (1963) of the signifi cance of social patterns in understanding language variation and change Labov chose to study variations in the diphthongs [ai] and [aυ]. We focus on the first diphthong only, which occurs in the lexical set price, white, right. On Martha’s Vineyard, the main variants of the variable (ai) were the [ai] pronunciation common in the surrounding mainland area known as ‘New England’ and a centralised pronunciation [əi] Labov undertook sixty-nine tape-recorded interviews, during which variation along a number of dimensions including ethnicity, occupation and geographical location became apparent. Age Group 75+ 61–75 46–60 31–45 14–30 index for (ai) 25 35 62 81 37 6 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali Labov used a scoring system of 0 for [ai] and 3 for [əi]. The intermediate variants were assigned values of 1 or 2. Labov argued that these ups and downs could be related to changes in speech norms over time in Martha’s Vineyard. Labov’s New York study Pilot Study:The department store study Labov was able to gather answers from 264 unwitting subjects. All in all, over 1,000 tokens of the variable (r) were collected (multiplying the number of speakers by four for the number of tokens) Some 62 per cent of Saks’ employees, 51 per cent of Macy’s and 20 per cent of Klein’s used [r] in at least one of the four tokens. Large study: New York Labov used a ten-point socioeconomic scale, devised earlier by the sociological research group. It was based on three equally weighted indicators of status: occupation of breadwinner, education of respondent and family income. On a ten-point scale, 0–1 was taken as lower class, 2–4 as working class, 5–8 as lower middle-class, and 9 as upper middle-class. The main variants of the study were (th) and (r) variables LMC’s position in the class hierarchy, reflecting the wishes of its members to distance themselves from the working class and to become more like the upper middle class. In this sense, hypercorrection denotes the use of a particular variant beyond the target set by the prestige model. Task Extract adequate numbers of tokens of a relevant linguistic variable; engage in a simple quantitative analysis; discuss the relationship between the use of different variants and the social background of speakers, as well as contextualise the results of their analysis by assessing language variation and change within a broader local, regional or national context. Criticism Recent approaches, however, whilst accepting the basic framework (e.g. the linguistic variable), have suggested that sociolinguistic variation studies have been sociologically naïve by correlating isolated social facts about a speaker (e.g. their gender, their social class, their ethnicity) with language use, rather than observing how social groups form and evolve and analysing the dialect that emerges from that social practice. 7 Sociolinguistics (Lecture #2) Instructor: Moazzam Ali Penny Eckert (2001). She engaged in extensive ethnographic fieldwork in a secondary school in Detroit in order to gradually piece together a picture of who hung out with who, who were the central members and the less central members of the emergent groups and so on. She was then able to plot group membership against a large number of linguistic variables. Her research is particularly important in making us realise just how gross categories such as 'female' or 'adolescent' or 'working class' are, lumping together very different people into the same group, and that a sensitivity to how real groups of people are formed and maintained provides a very rich seam for future sociolinguistic analysis. 8