Handout 3 Asking Better Questions

advertisement

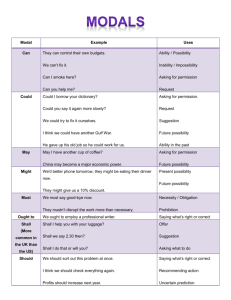

Asking Better Questions Why ask better questions? What do we mean by better questions? How do we go about formulating more challenging questions? How do we give all students more support and help to answer more challenging questions? Asking Better Questions Contents Page Page Setting the context 3 Reading 1 4 Bloom’s taxonomy Reading 2 6 Spot the difference Reading 3 9 Some ideas for asking better questions Reading 4 10 Using questions effectively Four strategies for devising effective questions Ideas for asking questions better activity Questioning activity Spot the difference answers 19 © Cambridge Education 2010 Copyright in this document belongs to Cambridge Education Limited and all rights in it are reserved by the owner. No part of this document or accompanying material may be copied, transferred or made available to users other than the original recipient, including electronically, without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Cambridge Education 1 Asking Better Questions “The most successful teachers all engage in above average levels of interaction with the students. This appears to be an important determinant of student progress.” Maurice Galton and Brian Simon “Many teachers without intending it constrict the ways in which students are able to participate in lessons and then complain when children will not talk.” Douglas Barnes “A good question is an invitation to think, or to do. It stimulates because it is open-ended, with possibilities and problems. A good question will generate more questions.” Robert Fisher “Successful people ask better questions and as a result get better answers.” Anthony Robbins Cambridge Education 2 Asking Better Questions Setting the context Questioning is one of the four practical areas of assessment for learning: Sharing learning intentions and success criteria with students Asking better questions: using questions that cause thinking and giving students more support to answer them Making feedback count: improving the quality of verbal and written feedback you give to students Promoting assessment by students: developing peer and self assessment to help students to give each other feedback as they are learning The diagram below shows the links between the four areas of assessment for learning. Questioning plays a crucial role in 3 and 4. Formative assessment has four crucial elements 1. Learners being clear about what they can do now that shows they are operating at level X 3. 4. 2. Learners knowing what they need to do in the future to show they have reached level Y Learners knowing what strategies they need to use to bridge the gap between X and Y and being able to use these strategies to bridge the gap for themselves Actively involving learners in assessment rather than promoting assessment by students: developing peer and self assessment to help students give each other feedback as they are learning Cambridge Education 3 Asking Better Questions Reading 1 – Bloom’s Taxonomy The “Taxonomy of Cognitive Objectives” was first developed by Benjamin Bloom in the 1950’s. It was revised in the 1990’s by Lorin Anderson. 1. Remembering: can take various types of information and recall it when needed. 3. Applying: can use a learned skill in a new situation. 5. Creating: can combine existing elements to create something new. prompts prompts prompts What happened after...? Is there a better solution...? How many....? Do you know of an instance where....? Judge the value of.... Can you apply this method to some experience of your own...? Defend your position about.... What facts can change if....? How would you feel if...? What changes would you recommend and why? What do you think about...? Why do you think that? Who was it that...? Who spoke to....? Find the meaning of... Which is true...? Would this information be useful to you if you had to...? Could this have happened in....? 2. Understanding: can give meaning to information at a basic level. 4. Analyzing: Can break down information into parts and relate the parts to the whole. 6. Evaluating: can make an objective judgement about the value of something based on a recognised standard. prompts prompts prompts Can you write in your own words...? How is this similar to...? Can you design a ...to...? Which event could not have happened if...? What do you think...? What is a possible solution to....? What was the main idea of...? How was this similar to...? What would happen if...? Can you distinguish between...? Why did...occur? Can you provide an example of what you mean by...? What are some of the problems of...? Can you think of some new and unusual uses for...? What was the turning point in the story...? How would you devise a way to...? Can you develop a proposal that would....? Cambridge Education 4 Asking Better Questions Examples of different levels of questions Goldilocks and the Three Bears A topic on weather The Second World War remembering: remembering: remembering: What happens in the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears? What kinds of weather do we get? What were evacuees and what happened to them? understanding: understanding: understanding: Why did Goldilocks like the little bear’s bed best? Why we need to know about the weather? Why were children evacuated from the cities? applying: applying: applying: What would you have done if you were Goldilocks? How does the weather affect us? What would it have been like to be an evacuee? analyzing: analyzing: analyzing: Was Goldilocks a good or a bad girl? What problems are changes in the weather causing the world? What were some of the problems that the people taking the evacuees might have had? evaluating: evaluating: evaluating: Which part of the story of Goldilocks did you like best? What have you learned about the weather? What more do you need to find out about the home front during the Second World War? creating: creating: creating: Can you make up a different end to the story? Compose a poem about the weather. How could the evacuation have been handled better? Health Warning Don’t get hung up on the categories. You will note that some of the questions above especially the higher order ones – might belong equally well in more than one category. Also, don’t think that students need to be able to answer the lower order questions before they can tackle the higher order ones. Learning doesn’t always work that way. Cambridge Education 5 Asking Better Questions Reading 2 – Spot the Difference The first episode is an extract from a lesson about electricity: Teacher: Teacher: Teacher: Teacher: Jay: Teacher: Carolyn: Teacher: Teacher: Jamie: Teacher: Teacher: Richard: Teacher: Carolyn: Teacher: Jamie: Teacher: Teacher: Rebecca: Teacher: Teacher: Right. I want everyone to concentrate now, because you need some information before you start today’s experiment. OK today we are going to find out about these … Holds up an ammeter. Anyone know what we call these and where you might find one? Starts to walk round and show groups the ammeter. Two hands go up in the class. Look carefully. Where have you seen something like this? You might have seen something like it before. What is it involved with? It’s got a special name … Three more hands go up. The teacher selects one of these students. Yes … Jay? In electricity, sir. That’s right. You can use these in electric circuits. Anyone know what it is called? This word here helps. Can you read what it says? Carolyn? Amps. And what is this instrument called that measures in amps? Pause of 2 seconds. No hands go up. No? No-one? Well, it’s an ammeter because it measures in amps? What’s it called, Jamie? A clock, sir. You weren’t listening Jamie. It might look like a clock but it is called an …? The teacher pauses and looks round class. 6 hands shoot up. Richard? An amp meter sir. Nearly. Carolyn? An ammeter. Thank you. What’s it called Jamie? An ammeter. That’s right. An ammeter. And where do we find these ammeters? Monica? Monica shrugs her shoulders. 6 children have their hands raised. No idea. Tell her Rebecca. In electric circuits. Good. I am starting to spot which of you are sleeping today. Are we with it now Monica? Monica nods. Right. Now we are going to use these ammeters in our practical today and so gather round and I will show you how it works. Quietly please. Cambridge Education 6 Asking Better Questions This second extract, from a lesson about photosynthesis, was taken some 7 months later: Teacher: Teacher: Teacher: Teacher: Teacher: Monica: Teacher: Jamie: Teacher: Jamie: Teacher: Teacher: Richard: Susan: Teacher: Tariq: Teacher: We are going to look at the way plants feed today. I know you’ve done some work on this in your primary school and I am going to give you time to think that over and to tell your neighbour about what you know, or think you know already. Students start looking at one another and a few whispers are heard. Hang on. Not yet. I want to give you something to think about. The teacher produces two geranium plants from behind his desk. One is healthy and large and the other is quite spindly. Now when Mrs James potted these two plants last spring, they were about the same size but look at them now. I think they might have been growing in different places in her prep room. I also think it’s got something to do with the way that plants feed. So have a think, then talk to your partner. Why do you think these plants have grown differently? The class erupts into loud discussion in pairs. The teacher goes over to a side bench and checks apparatus. After 4 minutes, the teacher returns to the front and stops the class discussion. OK. Ideas? About half the class put up their hands. Teacher waits for 3 seconds. A few more hands go up. Monica – your group? Pair? That one’s grown bigger because it was on the window. (pointing) On the window? Mmm. What do you think Jamie? We thought that … You thought …? That the big ‘un had eaten up more light. I think I know what Monica and Jamie are getting at, but can anyone put the ideas together? Window – light – plants? Again about half the class put up their hands. The teacher chooses a child who has not put up his hand. Richard. Err yes. We thought, me and Dean, that it had grown bigger because it was getting more food. Some students stretch their hand up higher. The teacher points to Susan and nods. No it grows where there’s a lot of light and that’s near the window. Mmm. Richard and Dean think the plant’s getting more food. Susan … and Stacey as well? Yes. Susan thinks it’s because this plant is getting more light. What do others think? Tariq? It’s the light causes photosynthesis. Plants feed by photosynthesis. The teacher writes photosynthesis on the board. Who else has heard this word before? The teacher points to the board. Almost all hands go up. Cambridge Education 7 Asking Better Questions Teacher: Teacher: Carolyn: Jamie: Teacher: Teacher: Dean: Richard: Dean: Teacher: Richard: Teacher: OK. Well can anyone put Plant, Light, Window and Photosynthesis together and tell me why these two plants have grown differently? The teacher waits 12 seconds. 10 hands went up immediately he stopped speaking. 5 more go up in the pause. Okay. Carolyn? The plant … The big plant has been getting more light by the window and because plants make their own food by photosynthesis, it’s … Bigger. Thanks Jamie. What do others think about Carolyn’s idea? Many students nod. Yes it’s bigger because it has more light and can photosynthesise more. So Richard and Dean, how does your idea fit in with this? It was wrong sir. No it wasn’t. We meant that. Photosynthesis. Plant food. Yeah. So. Can you tell us your idea again but use the word photosynthesis as well this time? Photosynthesis is what plants do when they feed and get bigger. Not bad. Remember that when we come to look at explaining the experiment that we are going to do today. Source of extracts: Paul Black et al “Working Inside the Black Box.” Cambridge Education 8 Asking Better Questions Reading 3 - Some ideas for asking better questions Reflect on why you ask questions It has been said that a classroom is the most complicated social system in the universe, and this is a claim that resonates with teachers. It follows that much of what teachers do on a daily basis is intuitive and instinctive. It has to be for us to cope, let alone do a good job. So questioning – as one of the basic tools of our trade – is intuitive. We are not often aware of how many questions we are asking let alone what kinds of questions we are asking. It is therefore worth standing back and reflecting on this area of work. Quite a bit of research has been done into teachers’ questioning, and much of it suggests that a very small percentage of questions that teachers ask are “higher order” questions. These encourage students to talk and think. Ted Wragg’s (1993) analysis of a thousand teacher questions gave the following breakdown: Encouraging pupils t o t alk and t hink (e. g. why is a bird not an insect?) , 8% Checking for knowledge and underst anding (e. g. how m any legs has an insect ?), 35% M anagerial quest ions (e. g. who fi nished all t he questions?) , 57% What do you think would be the average breakdown in your classroom on an average day? Do you think it would vary depending on: The age group you are teaching? The topic you are teaching? Whether you are interacting with the class as a whole, with a group of students or with an individual? Have you ever thought of recording yourself and doing analysis? questioning the focus of a classroom observation by a colleague? Cambridge Education 9 Or of making Asking Better Questions Reading 4 - Using questions effectively Some questions are better than others at providing teachers with assessment opportunities. Changing the way a question is phrased can make a significant difference to: The thought processes students need to go through The language demands on students The extent to which students reveal their understanding The number of questions needed to make an assessment of students’ current understanding For example, a teacher wants to find out if students know the properties of prime numbers: The teacher asks “Is 7 a prime number?” A student responds, “Err…Yes, I think so”, or “No, it’s not.” This question has not enabled the teacher to make an effective measurement of whether the student knows the properties of prime numbers. Changing the question to “Why is 7 an example of a prime number?” does several things: It helps students recall their knowledge of the properties of prime numbers and the properties of 7 and compare them. They then decide whether 7 is an example of a prime number. This question requires students to explain their understanding of prime numbers and use this to justify their reasoning. The response requires a higher degree of articulation than “Err…Yes, I think so.” An answer to the question might be: “Yes, because prime numbers have exactly two factors and 7 has exactly two factors. So 7 is a prime number.” It also provides an opportunity to make an assessment without necessarily asking supplementary questions. The question, “Is 7 a prime number?” requires follow-up questions to get a full response on which to make an assessment. Here are some other types of questions that are also effective in providing assessment opportunities in mathematics: How can you be sure that…? What is the same and what is different about…? Is it ever/always true/false that…? Why do _, _, _ all give the same answer? How do you…? How would you explain…? What does this tell us about…? What is wrong with…? Why is _ true? Source: QCA, England 2003 Cambridge Education 10 Asking Better Questions Four strategies for devising effective questions 1 Provide a range of answers This involves asking a question and giving a range of possible answers which include definite yes answers, definite no answers and some ambiguous answers. Dylan Wiliam (2006) gives an example of how this works using an example of a range of answers from a secondary school science lesson: What can we do to preserve the ozone layer? Reduce the amount of carbon dioxide produced by cars and factories Reduce the greenhouse effect Stop the cutting down of forests Limit the number of cars that can be used when the ozone level gets high Properly dispose of air-conditioners and fridges The teacher then asks the students to hold up one, two, three, four or five fingers depending on whether they think the answer is A,B,C,D or E. From this she knows whether the students have learnt or need more teaching. Another teacher gets the students to group with others who have the same answer: they go to a corner of the room and plan together how they are going to persuade the students in the other corners that they are wrong (the correct answer is E because it is a question about the ozone layer not global warming). Other examples……. What do we need for life? water/telephones/clothing/cars/shelter/food Are these foodstuffs good for you? chocolate, fruit, milk, meat, fat, sugar, water, butter, margarine, rice, pudding, motor oil, black pudding Which words are verbs? door, run, climb, red, slide, spill, cycle, shout Which things are needed to plan a route? compass, watch, map, GPS, trundle wheel, car, flag, atlas, globe Which of these languages features would you need to use if you were going to write a diary entry? formal language, past tense, abbreviations, technical language, named people, present tense, informal language What makes a good school council member? a good reader, a chatter box, a clear speaker, a good listener, a good writer When something unexpected happens, how do you feel? proud, worried, aggressive, anxious, jealous, happy Cambridge Education 11 Asking Better Questions 2 Turn the question into a true or false statement This involves turning a question into a provocative statement and asking students to work with a learning partner to take different points of view and to make use of what they know to argue the case. Closed questions with single correct answers are not as effective as those which need an explanation. Some examples are: No food is unhealthy. Agree or disagree? This picture shows a Viking. Agree or disagree? Everything is alive. Agree or disagree? Goldilocks didn’t deserve to be saved. Agree or disagree? All bullies are bad people. Agree or disagree? Money brings you happiness. Agree or disagree? Shylock was not a villain but a victim. Agree or disagree? The moon is a source of light. Agree or disagree? Multiples of 3 are always odd numbers. Agree or disagree? Drugs in sport are morally wrong. Agree or disagree? All animals are predators. Agree or disagree? 3 Don’t ask the question – give the answer and ask why it is correct This involves giving students the answer and asking them how they think the answer might have been arrived at, or why they think it is correct. This changes the focus from the answer to discussing the reasons for the answer. Some examples are: Instead of asking…. Is 7 a prime number? Which shape is this? Which genre is this? 4 Is this character trustworthy? Is this a regular verb? What kind of film is Star Wars? Can 7/9 be simplified? Ask….. Why is 7 a prime number? How do you know this is a triangle? How does the first paragraph let you know this is a ghost story? What behaviors make you think this character is not trustworthy? Why is this a regular verb? Why is star wars a science fiction film? Why can 7/9 not be simplified? Ask questions that explore opposites, differences, categories and exceptions This involves encouraging students to compare and contrast, to think about what is the same and what is different, to categorize and look for exceptions right and wrong. They can be used as a stimulus for class, group or paired discussion. Some examples are: Cambridge Education 12 Asking Better Questions Why are these shapes quadrilaterals and some not? Why does this circuit work and this one doesn’t? Why does this story opening work and this one doesn’t? Why is a dandelion a weed and a daffodil not? Why is this calculation right and the other one wrong? Is grass alive or dead? Is a bird an insect? Or a camel is not an insect. Why not? Cambridge Education 13 Asking Better Questions Ideas for asking questions better activity Make sure that you know what the following strategies are. Swap notes on which you have used and what has worked, or not worked for you. 1. Wait time 2. No hands up 3. Think, pair and share 4. Show-me boards 5. Signals for understanding 6. Take the answer around the class Cambridge Education 14 Asking Better Questions 1 Wait time Increasing wait or think time is an attractive idea, because it offers so many potential advantages and seems very simple and easy to do. But in practice it can be difficult to start with for both teachers and students when they are not used to it. Teachers find it really hard not to simply go for an answer, or rephrase the question almost immediately after asking it. They talk about the pause feeling unnatural at first, both for them and for students. Leaving too much wait time can be painful for students, and can actually lead to less discussion. Teachers also find it very hard to slow the pace of discussion in principle if they feel under pressure to cover content. It’s best to tell the class that you are going to make a change and explain why. You could then use some techniques to encourage the habit – particularly with classes where there are behavior issues, or where many students find it hard to focus and concentrate. Many secondary teachers avoid using the term “wait time,” and use terms such as “think” time, “jot” time or “talk” time instead. They find that combining wait time with other ideas in this section such as “Think, pair and share” and “Ask for five” can help to make it work – especially to begin with. You can also combine wait time with prompting questions to keep the discussion going, for instance: Can we add to Tom’s answer? Can you put Jenny’s answer into your own words? Well, if you are confused, you need to ask Jim a question. Which part of Sarah’s answer do you agree with? Can someone improve on Paul’s answer? 2 No hands up Some teachers combine wait time with no hands up when they ask a question. Under this system, everyone is expected to be ready to answer the teacher at any time after the wait time, even if it is an “I don’t know.” The “no hands” rule can completely change the dynamic in the classroom. It requires everyone to be focused and to at least attempt to come up with an answer. It is no longer possible to sit on your hands and then feel aggrieved if the teacher picks on you, despite the fact you didn’t have your hand up. Because it is such a radical change, however, both teachers and students find it difficult at first. Confident and keen students often resent the change and can’t stop putting their hands up. Less confident and less motivated students find it hard to respond and quickly say they don’t know. But when teachers persevere and combine it with other strategies that make it easier and help develop a climate where it is OK to be wrong then it becomes easier for everyone. Cambridge Education 15 Asking Better Questions 3 Think, pair and share Think, pair and share is a well-used technique for encouraging classroom participation and interaction. Its particular value lies in the way it allows involvement to grow gradually through individual reflection that is shaped and developed by accommodating other views and ideas. Because of this, it provides an easily managed but structured approach to classroom interaction. First of all, students are asked to think of or write down as many answers, ideas or suggestions as they can think of on their own (think). Then they are asked to pool their ideas with a partner (pair) and finally the teacher opens the discussion up for contributions from the class as a whole (share). This simple strategy helps all students to learn by encouraging a sustained interaction between thinking and talking, both individually and in groups. Putting a timescale on the first two stages e.g. one minute to think, two minutes to pair can help students to focus on task. 4 Show-me boards Class sets of small write-on, wipe-off boards have been used by primary teachers for some time now – especially in mathematics – to ask for more detailed and sophisticated whole-class responses. Some maths departments in secondary are now using them. At a simple level, the students can simply write the answer to a sum on the board, or they can be asked to choose between two alternative solutions by writing “a” or “b” on the board. Boards can also be used for more open-ended responses – across a range of curriculum areas – where students are asked to generate a number of examples, or a range of ideas or suggestions. 5 Signals for understanding This is one of the most popular and most controversial of the practical ideas tried out during the assessment for learning initiative. Signaling understanding broadly takes three forms: It can be initiated by individual students during a class lesson to let the teacher know he or she is going too fast or the student does not understand. It can be initiated by the teacher to get a picture of the understanding of the whole class at the end of a lesson or at key ‘hinge points’ during the lesson. It can be used by students during desk work to show when they are stuck and need help from the teacher. The methods used by students to signal can be many and varied. The three most popular ones are traffic lighting, “thumbs” and “fist and palm.” Cambridge Education 16 Asking Better Questions 6 Take the answer ‘round the class Weak or incomplete answers are actually good starting points for effective classroom discussions involving all the students, those who know the answer or have better answers and those who do not. So, if a student gives an answer that needs improvement, don’t respond directly take the answer round the class by saying, “Wait there ‘till we see what others think” and gather some answers from other students. Then bring these answers back to the first student and ask, “Which answer do you like best?” This technique involves the rest of the class while still keeping the first student listening and thinking. It is most effective if you use it regularly and always bring the answer back to the original respondent. Cambridge Education 17 Asking Better Questions Questioning Activity Not all questions can be planned. Indeed most questioning in a lesson is likely to be asked in response to students’ responses to your questions, and of course, this has to be done off-thecuff. However, research shows that where teachers plan at least some of their questions in advance rather than simply going into a lesson and asking questions off the top of their heads, the lessons are more successful. This does not mean that all questions can or should be planned in advance. We need to be able to improvise and go with the flow: This activity is designed to give you an opportunity to: 1. Practice planning questions for a part of a lesson. 2. Present your plan with another group. 3. Give and receive feedback on the effectiveness of the plans. TASK Decide on a lesson, theme or topic relevant to the age and stage you are teaching or your subject area. Plan up to six questions which will help you to achieve the learning intention of the lesson. Consider using one or two key questions that explore and develop understanding. Think about how you could structure and sequence questioning: you might begin with simple questions which may be closed and ask for recall. Work up to more complex questions which may be open and require thought – use Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide. Be prepared to report back to the larger group of any issues that arise about planning questions. Cambridge Education 18 Asking Better Questions Spot the Difference Answers Teacher used prior knowledge Subject matter was more accessible: concrete situation within their experience Used knowledge they already have Got most of the information from them Worked from their answers more Teacher used a variety of different techniques Introduction more focused and specific; gave students information to get them thinking Paired activity – time to discuss and think Used wait/thinking time Asked students who did not have their hands up Took a question ‘round the room Took questions back to students rather than answering them Teacher’s language was different Fewer guess what I am thinking, questions and judgments (e.g. that’s right, good, right, nearly) Was open to wrong answers More positive encouraging tone Used a variety of prompts to stimulate thinking (e.g. ideas? Mmmmnn. What do you think? You thought? I think I know what you are getting at… OK) Students respond differently More interaction: teacher-student; student-student; student-teacher More discussion: duration of lesson might be longer More students responding More students giving longer responses More students willing to take risks with answers Cambridge Education 19 Asking Better Questions Notes Cambridge Education 20 Asking Better Questions Notes Cambridge Education 21 Asking Better Questions Notes “This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof by Cambridge Education and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Neither Cambridge Education nor Mott MacDonald accepts any responsibility for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned.” Cambridge Education 22 Asking Better Questions The seven big messages about teaching 1. Teachers make a difference. Young people need the help of adults to learn, especially in the early years of life. Teachers have the power to create conditions that can help students to learn a great deal – or to keep them from learning much at all. 2. But they don’t make all the difference. We must stop pretending that schools and teachers can do everything. Most learning takes place outside school. Even in school there are limits to what teachers can achieve: they can influence learning but not determine it. 3. Teaching is a complex activity. There are no simple prescriptions for success. It is not just a matter of technique. To do it well requires a greater level of reflection and awareness than many activities and a willingness to deal with uncertainty and paradox. 4. We teach who we are. Teaching comes from within. How we relate to what we are teaching to our students depends on who we are as teachers and as people. Connecting with our students means giving a little of ourselves and being prepared to be vulnerable. Developing our practice depends heavily on self-knowledge and self-awareness. 5. Enjoying work with young people is crucial. Being a good teacher involves being able to empathize with young people: trying to see our students as they really are: both as people and as learners – what motivates them, how they prefer to learn and what they already know and understand. 6. Good teachers are knowledgeable. They have good understanding of what they are teaching as well as an ability to communicate that understanding to others. They also care about what they are teaching and can bring it to life. 7. Improvisation is as important as planning. Good teachers tend to make what is to be learned the focus of attention, but they don’t deliver to a set curriculum to a rigid plan. They are able to develop, refine and reinvent what is to be learned depending on what works for them and their students. Cambridge Education 23 Asking Better Questions Seven Big Messages About Learning Intelligence is not fixed Effort is as important as ability Learning is strongly influenced by emotion We all learn in different ways Deep learning is an active process Learning is messy We learn from the company we keep Cambridge Education 24