Lesson 9-1 - Religious Skepticism

advertisement

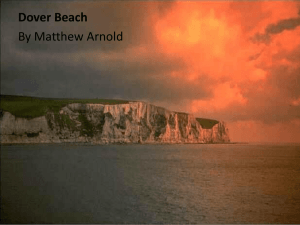

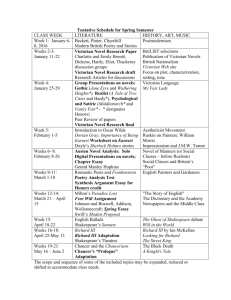

CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Charles Dickens, Matthew Arnold, and Thomas Hardy Marley's Ghost John Leech (1843) Illustration for Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Overview: We begin with Charles Dickens’s novel A Christmas Carol (18??), which is set in the financial district of London, where monetary concerns, a punishing work ethic, and child labour prevail. All of the human cruelties, selfishness, and hard-heartedness that Dickens witnessed in Victorian society are embodied in the main character of Ebeneezer Scrooge, who dismisses the celebration of Christmas, Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 1 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) and all Christian virtues, as “humbug.” We will examine closely, however, the gradual transformation of Scrooge into a man of love, charity, and compassion for the poor: What forces underpin that change? Why are supernatural elements necessary? Is the transformation convincing? Is Dickens advocating the need for a Christian ethic as a means of resisting the forces of materialism, industrialization, and individualism? Will it work? We continue this section on skepticism with two poets who similarly witness a change in human society, particularly concerning religious conviction, in the nineteenth century. Matthew Arnold expresses that change metaphorically as a “sea of faith” whose tide has retreated, leaving the world (the beach) as nothing but a bleak, barren stretch of hard, inhuman rock. A late Victorian poet (and novelist), Thomas Hardy goes further. He articulates the absence of God, replaced by a “crass casualty” (sheer randomness in the world) or an “Immanent Will” (cold, impersonal fate, which is indifferent to human desires). When God still does fleeting make Himself known to suffering humanity, He does so uncaringly or too mysteriously to embraced with conviction. Hardy, in particular, approaches the twentieth century almost prophetically, apprehending a dark, cruel era—ushered in by World War I—that he symbolizes with his “darkling thrush,” who has “so little cause for caroling” even during the season of Christmas. Objectives: To examine the varied ways in which writers during the Victorian period address the emerging skepticism towards Christian faith To identify the literary means of expressing that skepticism: in tone, metaphoric language, setting, character traits, irony, and form (prose or poetry) To question why, in broader social and historical terms, religious faith becomes increasingly fragile To consider the presence of hope, if it exists, in these selected works, and if so, how it is expressed Readings: Charles Dickens Matthew Arnold Thomas Hardy A Christmas Carol. Broadview Press edition (1999) “Dover Beach” (Coursepack of readings) http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/hardy/index.html “Hap” “The Darkling Thrush” “Channel Firing” “The Oxen” Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 2 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) 9.1.1. Literary Analysis and Study Questions Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843) As we begin the Victorian period, I have placed Charles Dickens' novel A Christmas Carol first in our reading list because it bridges the Romantic and Victorian periods in a number of important ways. It is, on the one hand, a work that deals with a number of quintessentially Romantic ideas: the virtues of childhood (and the relationship between the child and the adult); the importance of imagination (forms of thinking and experiencing the world that are not restricted to sense perception); the power of memory (as a source of salvation for the individual, and for society); contrasting depictions of rural and urban life; recognition of the dignity, cheerfulness, fortitude, feelings, and moral character of the poor; and the faith in idealism Scrooge visited by the Ghost of Jacob Marley (the belief that human character, and social ills, can be reformed, and that the magical powers of love and generosity do exist). Perhaps, you can find additional Romantic strands in the novel. If so, what are they? The novel is, on the other hand, a representative Victorian work. Its setting is, primarily, urban (not rural) and it deals realistically (not idealistically) with a number of problematic midnineteenth century social issues: narrow-minded mercantile pursuits, selfishness, child labour, forced workhouses for the poor, and inadequate education for children. Against that bleak social picture Dickens sets the joys of Christmas. Why has he done that? Where do these Christmas traditions come from, and what is their purpose in the novel (read the introduction in our Broadview text carefully)? What is Christian about this novel? Does the novel critique urban life (as the Romantics did), or does it propose a way of living in the city that can foster individual integrity and wholeness, an awareness of community and social harmony, generosity, love, and domestic happiness? As you read the novel, use these elements of fiction as the basis of your analysis: Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 3 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) Character: Is Scrooge a flat or round character (or both)? What are his initial character traits? (How does the narrator describe them colourfully?) How does he change? Is the transformation convincing? Does Scrooge appeal to the reader as a character? Why or why not? Plot: What initiates Scrooge’s reform? Why is the force supernatural rather than real? (Must the spirit world step in where humans have failed; is a supernatural realm, all but forgotten in a money-driven city, integral to the fullness of human life?) What is significant about the content of each ghost’s visions, and why do they appear in the order that they do? Does the novel have a climax? If so, where is it? Themes: What is the significance of the following themes in the book: the restorative power of memory; the influence of time (should it be punctual and inflexible, or fluid and imaginative?); the power of childhood instincts (kindness, affection, love, imagination, delight, playfulness, joy) and its frailty in adult life; the second chance to live a good life; poverty (over richness) and the fortitude and cheerfulness that it builds; Christian virtues (what are they, why are they lacking, and why are they necessary?). Form: In form, A Christmas Carol is a conventional novel, to be sure, but Dickens has also conceived it, with originality, as a musical utterance, not only by naming it a Carol (rather than A Christmas Story or Tale) but also by designating each chapter a “stave.” Why do you think Dickens has conflated music (especially Christmas carol singing) with text (a written story)? Figures of Speech: irony, metaphor, metaphor: “solitary as an oyster” (40): In what specific ways is Scrooge like an oyster? Is this metaphor an effective one? How does is this image of an oyster very different from Ephraim’s “The Pearl”? irony: Stave Four: What dramatic irony occurs in this stave? In other words, what knowledge do we (the readers) share with Dickens that Scrooge lacks? Why has Dickens created that gap, or ironic incongruity? At what point does Scrooge gain full knowledge? Matthew Arnold, “Dover Beach” (1867) In form, we can call this poem elegiac: that is, a poem that laments the loss, or death, of someone or something. No person has died, here, but Arnold is “grieving” over the decline of religious faith in Victorian England. Conventionally, a formal elegy moves beyond grief to consolation; the speaker finds a way to overcome the loss, personally and publically. Does this poem offer consolation? Does the final stanza express any hope that the receding tide of faith might turn? Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 4 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) Cleverly, he uses a metaphor to express that loss: the receding tide on Dover Beach. The retreat of the water is like the erosion of religion. What is left behind on the beach (a faithless world) when the water (spirituality) has gone is nothing more than a barren, empty, dry, and rocky terrain. Do other aspects of the setting function metaphorically to reinforce the overall tone of loss? Is the “night” significant? What might the white “cliffs” suggest? Does this poem contain any allusions? Does it refer to any passages from Scripture? Why or why not? What is significant about the inclusion of the classical (pre-Christian) Greek dramatist Sophocles? How would you characterize the poem’s musicality? What is its rhyme scheme? Why are the line lengths seemingly irregular, or do they fall into a carefully-constructed pattern? Does Arnold portray the waves as musical, too? If so, what kind of music are they making? The poem’s central theme, we might say, is “human misery” (18). Why is Arnold observing an “eternal note of sadness”? How, in many ways, is that theme reinforced throughout the poem, in imagery, sound, diction (word choice), setting, and first person narration? 9.1.2. Question for Blackboard Discussion Dyce, William. Pegwell Bay, Kent - a Recollection of October 5th 1858 (c. 1858-60) Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 5 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) Compare this painting to Arnold’s “Dover Beach.” The two works not only portray the same setting but also appear contemporaneously. Dyce’s painting was the product of a trip he made in the autumn of 1858 to the popular holiday resort of Pegwell Bay on the east coast of Kent. It shows various members of his family gathering shells. The artist’s interest in geology is shown by his careful recording of the flint-encrusted strata and eroded faces of the chalk cliffs. The barely visible trail of Donati’s comet in the sky places the human activities in far broader dimensions of time and space. The painting is, we might say, a largely scientific view of world: its tidal movements, seaside objects, ancient geology, and astronomical phenomena. Even the isolated human figures, seemingly oblivious to their surroundings, are determined to collect (in a scientific sense) the shells on the beach rather than to interact socially and meaningfully with each other, or to contemplate, in a spiritual way, the natural beauty of the scene as a manifestation of God’s wondrous creation. The colour, too, while beautifully subtle and evocative, is rather bland and clearly indicative of an approaching twilight hour, an indication, perhaps, of the draining away not only of water but also of light (both literal daylight and metaphoric spiritual light). What do you think? 1. Do the poem and painting express a similar idea: that the “Sea of Faith,” “once . . . full,” has now “withdraw[n]”? If so, by what specific means do poet and painter project that idea? 2. Alternatively, do the two works offer a different portrait of mid-Victorian society? If so, what is that difference? Thomas Hardy (1840 – 1928) We move, now, to the late Victorian period. Thomas Hardy, who established himself as a Victorian novelist, turned late in his career to writing poetry; in fact, he began his literary career as a poet, in the 1860s, quickly discovering the imperative to write novels, instead, to support himself financially. He returned to poetry late in his life with delight, after receiving harsh criticism of his final two novels, Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1890) and Jude the Obscure (1895), both of which made daring claims about social hypocrisy, the crippling effects of poverty, the nobility of a “fallen woman,” the constraints of conventional marriage, and the impossibility of perfect love. What distinguishes Hardy’s writing, both his novels and poetry, is his startling—some would say pessimistic—view of human existence. In particular, he sees irony as a central fact in human Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 6 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) existence: things are not what they should be, appear to be, or might be. A cosmic disorder, Hardy came to believe, underlies human experience: o Expectation does not produce fulfillment o Human aspirations and efforts are thwarted or dashed o Coincidental timing, circumstance, chance, and accident undo our expectations, ideals, and hopes. o Life is not harmonious and coherent (producing lasting marriage, deep friendships, family circles); rather, it is unharmonious and fragmented (consisting of conflict, isolation, and death) o Time is an implacable force that marches forward; it sweeps away the past, makes it irretrievable; it doesn’t fulfill hopes and ambitions; memory doesn’t offer consolation; time doesn’t unify the self, only shows divisions By the late 19th century, literature became increasingly pessimistic (Gerard Manley Hopkins, a deeply religious man, is an exception). Writers were critiquing the optimism of the Romantic era and anticipating, instead, the deeper skepticism, hopelessness, and bleakness that emerged in the 20th century, especially after World War I. Hardy, we could say, is a little ahead of his time in conceiving already of the absence of a benevolent God. “Hap” (1866) 1. What is Hardy’s philosophy: in other words, what is “hap”? (Be sure to use a dictionary to define this now archaic word.) Think about our contemporary related words: Happen: occur (chance or otherwise); good or bad fortune Happenstance: a thing that happens by chance Haphazard: by chance, randomness 2. How (and why) is Hap personified? What does it do? (Look carefully at the diction and images in stanza 2.) What oxymoronic (paradoxical) circumstances does Hap cruelly cause? 3. Why would Hardy conceive of this distant, impersonal force in place of a Christian God? Would anything in contemporary history, science, philosophy, or his own biography be influencing his thinking? “The Darkling Thrush” (1900) Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 7 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) 1. Form: the poem is an elegy: What dies? (Look carefully at the date of composition.) What abstract entity has Hardy personified, in death? Is the poem a conventional elegy? Does it offer consolation, after the grief? 2. Setting: Where and at what time of day does the poem take place? What overall “picture” of the landscape is presented? What images are prominent? Why? 3. The songbird tradition: How does Hardy both evoke this Romantic motif and rewrite it? Is the bird quite different from Shelley’s skylark? How? Why? Is Hardy rejecting idealism for harsh realism? 4. Speaker: Why is he alone? What frame of mind is he in? He hears the bird, clearly, but does he understand why it sings, when the world offers “so little cause for carolings”? Does feel hope or hopelessness (or both), as the new century dawns? “Channel Firing” (April, 1914) Note the setting of the poem, in two respects. First, it refers to the English Channel, the waterway that separates England from France. Significantly, its date indicates that it was written just months before the commencement of World War I. Hardy is referring to the practice gunfire that could be heard even at a distance from the England Channel. Prophetically, Hardy intuited, even in those preparatory months, the enormous—as the poem says, “apocalyptic”—significance of the approaching war. Second, we can imagine the setting in which Hardy wrote the poem to be that in the photograph below. Here, we see his study, in his home in the county of Dorset, on the south coast of England. As the caption below it indicates, Hardy enjoyed looking at his garden, which exudes an idyllic peaceful rurality and simplicity, quite at odds with the complexity, noise, and destruction that he associated with war. 1. What wakes up the dead people lying in the country churchyard? Who are they? Why are they—and not living human beings—the collective “speakers” of the poem? What mistake in their thinking do they make? How does God correct them? 2. God is present in the poem, but not in a conventional way. What is the tone of His voice? Is he pleased or dismayed with humanity? Why does he seem to laugh, even take pleasure in watching, as humans mess up the world (through war)? What is Hardy’s view of God, here? Is Hardy critiquing what he perceives as God’s unwillingness to intervene in human affairs and to set the world right? Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 8 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) 3. What does this poem tell us about Hardy’s view of war? Why does he conceive of it in apocalyptic terms, even in its preliminary stage of gunfire practice? What is the significance of the extraordinary ironic gap (incongruity) between the scale of the biblical apocalypse (in the Book of Revelation) and mere practice gunfire on the English Channel? Is he questioning the conventional view of war, in his time, as heroic, glorious, and patriotic, and seeing it, instead, as madness? Looking out the window of Hardy's final study at Maxgate Hardy designed the window of his study at Maxgate so that its central panes would not block his view of the garden. Much of his later poetry was written in this room, the furnishings and books of which are now in the Dorset County Museum, Dorchester. (http://www.victorianweb.org/photos/hardy/gallery.html) “The Oxen” (1917) We conclude our reading of Hardy with a Nativity poem, which may surprise us after our earlier encounter with his “Hap,” incomprehension of a “caroling” songbird, and a satiric treatment of God as a remote, cynical entity indifferent to human affairs. However, Hardy new the Bible well, as his numerous biblical allusions in his novels make clear, and he presumably harboured at least some Christian faith. Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 9 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Nine – The Victorian Period (1832 - 1901) 1. Setting: the poem is set on Christmas Eve, in rural England. It recounts a folk myth: that the oxen will kneel, in reverence, on this religious occasion. Notice how the rural people truly believe this supernatural occurrence. How is that unwavering faith conveyed? 2. Identify, too, the symbols: are the flock of sheep and the shepherd more than just that? 3. Form: note the two part structure of the poem. What distinguishes the first part from the second, in setting (where is the speaker, now?), time (is he older?), tone (has doubt replaced conviction), imagery (is it still pastoral?), and religious conviction? Lesson 9.1 – Religious Skepticism: Thomas Hardy, Charles Dickens, and Matthew Arnold ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 10