Principle (li) and Place (topos): Correlative Concepts

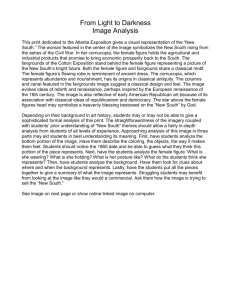

advertisement

Principle (li) and Place (topos): Correlative Concepts? Michael Harrington, Duquesne University When Aristotle provides Western philosophy with its first major discussion of the concept of place, he associates it closely with the part-whole relation: a thing is related to its place as a part is related to its whole. Though Aristotle goes on to develop a different and more famous understanding of place (as the interior limit of the surrounding body), many later Western philosophers will find the part-whole relation to be more useful. Certain Neoplatonists, in particular, think of place as nothing but what relates parts to their whole. In the words of the Neoplatonist Damascius, every topos or place is a syntoposis—that is, a setting of something in relation to other things. When things are in their places, that is, in their proper relationship with other things, they are then able to be themselves most effectively. The feet, to use one of Damascius’ examples, can only serve as feet if they are placed below the rest of the body. The language used in Western discussions of place has already appeared in several accounts of the classical Chinese concept of “principle” (li 理). Chad Hansen has interpreted principle in terms of part-whole relationships and, more recently, Brook Ziporyn has described principle (or “coherence,” as he prefers to translate it) as a center-periphery relationship. Neither of them develops this vocabulary into an explicit theory of place, or as a way of showing the relation between principle and place, though the concluding pages of Ziporyn’s 2012 book, Ironies of Oneness and Difference, do contain some provocative statements on how the geometrical figures of the Book of Changes and similar works are a “spatial model” of a “system of harmoniously grouping coherences.” That is, we may see the Book of Changes and similar works as models of various center-periphery relationships, each of which can be put into practice in a number of concrete contexts. There is good reason, then, to see what can be discovered if we apply the conceptual vocabulary developed in classical Western discussions of place to the study of the Book of Changes. The Song-dynasty commentary on the Book of Changes composed by Cheng Yi is particularly useful in this regard, since he frequently and consistently discusses the idea of a “constant principle.” We will find that the lineaments of Cheng Yi’s constant principle could just as easily be those of the Neoplatonic syntoposis. The point here is not to compare two independent theories of place, or to form a more complete theory by combining them, but to use one theory as a tool in unearthing elements that would otherwise remain hidden in the other. Cheng Yi, for instance, does not have any explicit theory of place, though the raw material for such a theory is scattered throughout his commentary. It is helpful, then, to think through his statements about principle in the context of the classical Western theory of place. Likewise, the Book of Changes can shed new light on the connection between place and time as described in classical Western theories. Though place and time appear together in classical Western accounts from Aristotle onward, these accounts generally draw no clear connection between them, as though one could possibly have the one without the other.