Textual Editing Project-Description and DEADLINES

advertisement

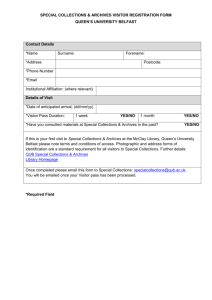

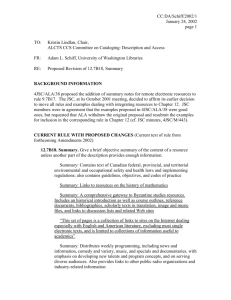

ENGLISH 6110: SEMINAR IN AMERICAN LITERATURE I Fall 2010 Dr. Patrick Erben TEXTUAL RECOVERY AND EDITING PROJECT GOALS OF THE ASSIGNMENT Many of the texts we are read this semester have only recently become available for a general audience and may have been entirely unknown for several centuries since their original composition or publication. As in the case of Susanna Rowson, many writers of fiction had a single enduring success, but their larger work has remained neglected or obscure. This assignment will give you a sense of the exciting work involved in discovering, editing/translating, and presenting with a scholarly introduction an early American text that has been unknown or generally unavailable in a modern edition. (For the sake of this assignment, I define “early American” as the anything originally published or written before 1900; usually “early American” is defined as the period up to 1800 or 1820/1830.) Beyond locating a suitable text, you will choose, transcribe, and annotate a representative textual selection (up to 10 pages) and prepare a substantial scholarly introduction (8-10 pages), providing biographical, historical, or literary background information. The introduction may also place the work into the context of the readings we have discussed throughout the semester (if applicable; e.g. if you recover another work of fiction). COMPONENTS OF THE PROJECT: 1. “Discovery”: Finding a Source Text The search for hitherto neglected or unknown texts has been considerably simplified through the advent of digital search engines and electronic databases. Ultimately, it is most exciting to browse physically through dusty archives and “discover” marvels of American literary history such as a missing ur-text of Franklin’s Autobiography (this example is completely fictional, so don’t go searching for this one!). However, modern databases can provide you an exciting glimpse of the diversity and extent of publishing and writing in early America. Your assignment is to find a text that has never been published (a manuscript) or has not been republished since colonial or early American times. If you find an edition of a text published within this period which has been republished later, you may still use it as long as it is not generally or widely available (if in doubt, please consult me!). You should use WorldCat (see databases) to ascertain whether a text has been published in a recent edition or not (further resources for this search can simply be Google or amazon.com). Once you have excluded the possibility that your text has been republished (or at least republished in a widely accessible source), print/photocopy/transcribe/photograph the entire text if feasible. This will enable you to make a decision about the selection you want to edit later and read the whole text. If this is not feasible (copying costs, manuscript too fragile to be copied, etc.), then you need to read the piece on location (at the archive) and transcribe directly from the source text. Laptops have made the work of the archival researcher much easier. 2 FULL TEXT DIGITAL/ELECTRONIC DATABASES: (AVAILABLE THROUGH OUR LIBRARY OR ON THE INTERNET) Annals of American History Full text of over 2000 primary documents in American history, including historical accounts, speeches, memoirs, poems, editorials, etc. Early Americas Digital Archive Collection of electronic texts and links to texts originally written in or about the Americas from 1492 to approximately 1820. Many of these texts are already transcriptions. If possible, try to find an original version of the text. Early American Fiction (University of VA) Includes nearly 200 volumes of early American fiction dating from 1789-1850; includes full color images of pages (many fall after 1865, but there are some earlier works). Digital Library of Georgia Georgia history and culture in digitized books, manuscripts, photographs, and other materials Early American Imprints, Series I. Evans (1639-1800) Definitive resource for information about every aspect of life in 17th- and 18th-century America, including literature, music, religion, and much more. Early American Imprints, Series II: Shaw-Shoemaker (1801-1819) Primary source collection with full-text access to the 36,000 American books, pamphlets and broadsides published in the early years of the 19th century America's Historical Newspapers 1690-1922 Early American Newspaper Series 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7, 1690-1922 and The Civil War: Antebellum Period to Reconstruction, 1843-1877, African American Newspapers, 1827-1998. Library of Congress: American Memory Project Full-text from the collections of the Library of Congress and other institutions, chronicling historical events, people, places, and ideas that have shaped America. African-American Poetry: 1760-1900 American Periodical Series (APS) Online Full-text of 1,100+ periodicals that first began publishing between 1740 and 1900 Search Engines for Researching Archives a. Archive Finder (including Archives USA); http://archives.chadwyck.com/home.do b. Archive Grid; http://archivegrid.org/web/index.jsp Also, please consider the resources listed in Frances Smith Foster’s anthology Love and Marriage! 3 SPECIAL COLLECTIONS/MANUSCRIPT LIBRARIES: Traditionally, archival research in special collections and manuscript libraries has been the only method to find unpublished or rare materials. Such archives range from divisions of university libraries to state or local historical societies to endowed institutions especially dedicated to the preservation of original source materials on a variety of subjects. Most of these institutions have not been able to enter each item in their manuscript collections into digital databases. Therefore, researchers who want to do work at these institutions can follow several search strategies: a) Rely on the expertise of the archivist/special collections librarian. b) Follow specific leads on authors or so-called “collections” or “papers.” For instance, a variety of items may be collated under the personal name of a certain collector who bequeathed his/her collection to the library. Or, a library may own a swath of documents relating to a certain individual c) Search in printed finding aides or collections guides published by the library. Some special collections libraries or archives located in the greater Atlanta area are: Georgia State University, Pullen Library Special Collections Emory University, Woodruff Library, Special Collections The University of Georgia, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript The Georgia Archives, Morrow, GA. http://www.sos.ga.gov/archives/ Other archives in the State of Georgia: Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, GA. http://www.georgiahistory.com/ List of Georgia Historical Societies: http://sos.georgia.gov/cgi-bin/ghor.asp 2. Introduction, including bibliography of secondary texts. Your introduction should provide relevant biographical, historical, or literary background information that will help the reader of the text place the work in a context, understand its literary techniques, or assess its cultural subjectivity. Please list all secondary works you used in researching this introduction. Note: I will conduct a workshop on the editorial process during a class meeting (October 11, 2010). 3. Transcription/Copytext Your first step should be to establish a copytext from which to work further. Thus, you will transcribe YOUR SELECTION from the source text into your word-processing program. All illegible parts of the text should be indicated as “lacunae,” i.e. square brackets that indicate omissions from the text [. . .]. (This issue primarily arises if you are working from a manuscript.) If you can make an educated guess as to a word or letter that is not legible, put this word or letter in square brackets [Franklin]; [Fr]anklin. Make a list of the type of changes you made (e.g. converting all long-s’s into regular s’s). Your final project should include a brief editorial note (I will provide examples) that states your editorial principles and overall changes you made to the original text. 4 4. Annotation of primary text. Once you have established a copytext, your work as an editor really begins. You need to establish a consistent practice of modernizing unusual or inconsistent spellings etc. In most recent editorial practices, these changes are kept to a minimum. Also, you need to annotate any names, places names, dates, or references that would have been familiar or accessible to readers at the time, but not readers today. Your annotations should not be interpretive, but rather informative. If you are doing a translation, you may provide alternative meanings that would influence the interpretation of the piece. All annotations should be done in footnotes. EXAMPLES The following edition of an early American manuscript book provides both an excellent example of a scholarly introduction as well as a useful precedent for editorial practices (annotations etc.): Wulf, Karin A. and Catherine La Courreye Blecki. Milcah Martha Moore’s Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1997. [PS530 M46 1997] I will also post a few examples by students on the website! DOCUMENT STYLE Please use MLA style for quotations, document format, citations in your introduction (all citations in your introduction should be parenthetical) etc. Annotations of the primary text should be in footnotes. ________________________________________________________________________ STEPS TOWARD COMPLETION OF THE PROJECT 1) PAPER PROPOSAL (DUE 11/1) a. In about 300-400 words (1-2 pages), identify the text you want to recover, edit, and introduce. Discuss briefly what you know about the author, period, genre, and general topic of the text. Describe the research you will do situate the text in its historical, literary, sociological, and cultural context (introduction). 2) ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY (DUE 11/1) a. Submit as a separate document with your paper proposal. This alphabetical bibliography (formatted MLA style) should list the secondary sources (i.e. literary criticism, historiography, etc.) as well as primary sources other than your recovered text which you plan on using for your introduction. You do not have to have read the sources yet; rather, simply say in one or at most two sentences what the source is generally about and how you will use it. 3) DRAFT (11/22) a. Your draft should be as close as possible to your final paper. It should include the primary text (or text selections), annotations, the introduction and a list of works cited (here, you only list the works you actually cite or reference in your introduction). 4) FINAL PAPER (12/6) a. The final paper should have all components included in a single document, following the following order: 5 i. Cover page, with cover art (preferably, a historical image relating to your text ii. Your introduction iii. Works Cited iv. Editorial Note v. The primary text or textual selections with annotations (as footnotes). 1. This section should begin with an MLA style citation of your primary text (including the archive or library owning an original manuscript, if applicable).