Session Five Notes

advertisement

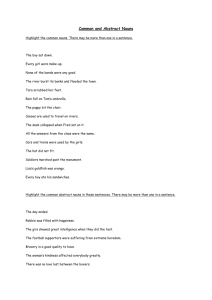

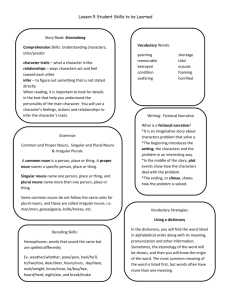

English 421 Semantics and Pragmatics Session Five Notes Goals/Objectives: 1) To examine the meaning and nature of nouns 2) To examine the nature of the so-called “has-relation” 3) To review concept of prototypes 4) To examine the notion of spatial parts 5) To examine the notion of metaphors 6) To examine the notion of hyponymy 7) To examine the notion of incompatibility Nouns Questions/Main Ideas (Please write these down as Nouns form the majority of words in the vocabulary of English you think of them) In contrast to the relatively unidimensional meanings of adjectives, nouns typically “denote rich, highly interconnected complexes of properties” according to our author Nouns The “things” denoted by some nouns have parts, which may figure in the noun’s meaning For example, a square has four equal sides and it has 90 angles In saying what a square is, one cannot avoid talking about its four sides and right angles Nouns Nouns can also be grouped into semantic categories For example, squares, circles, and triangles belong together as shapes Nouns can also be classified as being either count or mass nouns All this needs to be explained Nouns The has-relation The everyday words square, circle, and triangle are also technical terms in geometry, where they have tight definitions For example, a closed, straight-sided figure is a triangle if, and only if, it has exactly three sides Nouns In other words, there is an entailment here: 1) That figure is a triangle That figure has three sides For many words, however, we can only be sure that all the parts are there if the so-called “has-relation” is stated in terms of prototypes Nouns Prototypes are clear, central members of the denotation of a word Think of what you might advise a child drawing a face to put in: Probably eyes, a nose and a mouth How about a child drawing a house? Nouns Probably you would expect there to be a roof, a door, and windows Prototypes among the things denoted by the English word face have two eyes, a nose and a mouth However, this is also a face Nouns Nouns The face of a Cyclops, with its single eye, is a face, but not a prototypical face You can also have a windowless house, such as this: Nouns Nouns It may be incontestably a house, but it is not a prototype for the denotation of house in contemporary English Some information needs to be built into an understanding of these words that reflects certain semantic facts: Nouns A prototype face has two eyes A prototype face has a nose A prototype face has a mouth A prototype house has a roof A prototype house has a door A prototype house has windows Nouns Granted, prototype faces and house may have other parts besides those listed Cheeks and chin, etc. What is probably more important, though, are the many things that the prototypes do not have, like blemishes or a carport Nouns These, obviously, may be parts of many real faces and houses, respectively Restricted to prototypes, the has-relation makes available entailments For example: Nouns 2) There’s a house on the corner ‘If it is like a prototype for house then it has a roof’ 3) The child drew a face ‘If the face was prototypical, then the child drew a mouth’ Nouns In our previous discussion, entailments were introduced as guarantees Here, the guarantees are weakened by making them conditional on prototypicality Nouns The entailed propositions in 2 & 3 start with “if” because it seems that average English words are not as tightly defined as technical words like triangle Nouns Pragmatic inferences from the has-relation The has-relation, restricted to prototypes, is the basis for some of our pragmatic expectations in language use This can be seen in the switch from indefinite to definite articles Nouns A noun phrase that first brings something into conversation is usually indefinite – for example, marked by means of an indefinite article, a or an Nouns But on second and subsequent mention of the same thing in conversation it will be referred to by means of a definite noun phrase – marked by, for example, the definite article the As in the following example: Nouns 4) A: “I’ve bought a house.” B: “Where’s the house located?” NOT: “Where’s a house located?” 5) (a child showing off a drawing) C: “I drawed a face.” (adult responding to the child) D: “I like the face you drew.” NOT: “I like a face you drew.” Nouns However, if a whole that has a part has been mentioned, then the part can, on first mention, be referred to by means of a definite noun phrase, as illustrated in the following: Nouns 6) A: “I’ve bought a house.” B: “I hope the roof doesn’t leak.” 7) C: “I drawed a face.” D: “Where’s the nose?” Nouns Parts can have parts Words denoting wholes bear the has-relation to the labels for their parts But the parts can, in turn, have parts, and a whole can be a part of a large whole, as in the following: Nouns A suburb / \ has has streets (a street) houses (a house) has has curbs windows Nouns Interestingly, we can’t posit an inverse relationship to the has-relation, one that would guarantee the existence of the relevant large whole whenever a part of it is present This is because parts can exist in the absence of the larger whole Nouns For instance, Home Depot and Lowe’s keep stocks of windows for houses that have not yet been built Furthermore, the same kind of part can belong to different kinds of a whole A given curb need not be part of a street – it could be part of a parking lot Nouns Spatial Parts A prototype thing, such as a rock, can be said to have a top, a bottom, sides, and a front and back Two points need to be noted about these words Nouns One is that they are general: very many different kinds of thing – windows, heads, faces, feet, buses, trees, canyons, to randomly name just a few – have tops, bottoms, sides, fronts, and backs Nouns A thing has spatial parts, making the possession of such parts characteristic of prototypes in the thing-category The other notable feature of spatial part words is that they are often deictic Nouns Pragmatics enters the interpretation of deictic words The meaning of a deictic word is tied to the situation of utterance The front of the rock faces the speaker and the back of the rock faces away from the speaker Nouns The sides are to the left and right from the point of view of the speaker What counts as the top of the rock and what counts as the bottom of the rock depends on which way up the rock happens to be lying at the time of utterance Nouns However, many things – bus, for example – inherently have a non-deictic top, bottom, front and back, and sides The top of the bus is its roof, even in the dire case of one lying overturned at the side of the road Nouns The front of the bus is the driver’s end of it, regardless of where the speaker is viewing it from It is with things that do not inherently have these parts that the deictic top, bottom, front, back and sides come into play Nouns Notice that a rescue worker who is standing “on top” (deictically) of an overturned bus is not on the top (part) of the bus Here are some examples of things that have inherent spatial parts: People Houses Nouns Trees (top, base, sides) Hills (top, base, sides) Animals Pianos Here are some things that have spatial parts only deictically: Wheels Nouns Planets (in the talk of amateurs looking through a telescope) Trees (front, back) Hills (front, back) Ends and beginnings Long, thin things have ends Nouns Sometimes two different kinds of ends are distinguished: beginnings and ends Here are some things that prototypically have ends: Ropes (pieces of) string Nouns Roads Trains Planks Nouns denoting periods of time have beginnings and ends They also have middles A) day, week, month, era, term, semester, century Nouns B) conversation, demonstration, ceremony, mean, reception, process The words in B do not denote concrete entities that you could touch, but the events and processes that they can be used to refer to are nonetheless located in time and space Nouns Which is to say that it is reasonable to wonder when and where conversations, demonstrations, and so forth took place The can also have beginnings, middles, and ends (a full understanding of this will entail understanding verb endings) Nouns Some other parts The body is a source of metaphors For instance, losing one’s head, meaning “panic” Person is an ambiguous word denoting either a physical person – who can, for instance, be big or ugly Nouns Or the psychological individual – who can be kind or silly and so on The physical person prototypically has a head, has a torso, has arms, has legs, and has skin These parts and some of the parts they, in turn, prototypically have can be laid out thusly: Nouns A person has a head, a torso, arms, legs, skin A head has a face, hair, forehead, jaw A face has a mouth, nose, chin, eyes, cheeks A mouth has lips Nouns Remember that a semantic description is different from the compilation of an encyclopedia Semantics is not an attempt to catalogue all human knowledge Instead, semanticists aim to describe the knowledge about meaning that language users have Nouns Simply because they are users of the language Specialists will have more detailed vocabulary for talking about body parts But it is safe to assume that any competent user of English knows the meanings of these words Nouns A prototype chair has a back, seat, and legs Interestingly, the words back and leg are also body part labels The body part labels head, neck, foot and mouth are used to label a wide range of things Nouns For example, a mountain has a head and a foot Lampposts and bottles have necks Caves and rivers have mouths Presumably, this indicates a human tendency to interpret and label the world by analogy with what we know and understand Nouns Hyponymy This relation is important for describing nouns, but it also figures in the description of verbs and, to a lesser extent, adjectives It is c0ncerned with the labeling of subcategories of a word’s denotation: Nouns What kinds of Xs are there and what different kinds of entities count as Ys For example, a house is one kind of building A factory and a church are other kinds of buildings Nouns Further, buildings are one kind of structure; towers and dams are other kinds of structures The pattern of entailment that defines hyponymy is illustrated like this: 8) There’s a house next to the gate 9) There’s a building next to the gate Nouns 10) (8 9) 11) ( 9 8) If it is true that there is a house next to the gate, then (with respect to the same gate at the same point in time) it must be true that there is a building next to the gate It cannot be otherwise Nouns On the other hand, it we are given 9 as true information, then we cannot be sure that 8 is true It might be, but there are other possibilities For example, the building next to the gate could be a barn or any other kind of building Nouns That is why 11 has been scored through Though it could follow , 8 does not have to follow from 9 In the terminology of semantics, building is the superordinate for house and nouns labeling other kinds of buildings Nouns House, barn, church, factory, hanger and so forth are hyponyms of building It is possible to generalize about the pattern shown Nouns A sentence, such as 8, containing a hyponym of a given superordinate entails a sentence that differs from the original one only in that the superordinate has been substituted for its hyponym, as in 9 Nouns The sentence with the hyponym entails the corresponding sentence with the superordinate replacing it, but the entailment only goes one way – not from the sentence containing the superordinate (this doesn’t work so hot for negative sentences) Nouns This essentially highlights the fact that there being a building by the gate is a necessary condition for there to be a house by the gate If there is no building at the gate, then there cannot be a house there Nouns Intuitively, it is reasonable to say that ‘building’ is a component of the meaning of house A house is a ‘building for living in’ Prototypicality has to be brought into consideration for the has-relation, but is not needed for hyponymy Nouns Hierarchies of Hyponyms House is a hyponym of the superordinate building, but building is, in turn, a hyponym of the superordinate structure, and, in its turn, structure is a hyponym of the superordinate thing Nouns A superordinate at a given level can itself be a hyponym at a higher level, as in: Nouns Thing – superordinate of structure Structure – hyponym of thing; superordinate of building Building – hyponym of structure; superordinate of house House – hyponym of building Nouns The hyponym relation passes through intermediate levels in the hierarchy Which means that house is not only a hyponym of building, but is also a hyponym of building’s immediate superordinate, structure Nouns And, via structure, house is also a hyponym of thing Thing is a superordinate for all the words on lines that can be traced down from it in the hierarchy, and so on Nouns Thing – superordinate of structure, building, and house (and others words) Structure – hyponym of thing; superordinate of building and house Building – hyponym of thing and structure; superordinate of house House – hyponym of thing, structure, and building; superordinate of other words Nouns The significance of hyponymy passing through intermediate levels is that a hierarchy of this kind guarantees numerous inferences Thus, if someone who is speaking the truth tells us about a house, we know, with certainty and without asking, that the entity in question is a building, a structure, and a thing Nouns Obviously, such hierarchies show only a fragment of the possibilities There are many other kinds of things, for example And there are also words that are hyponyms of house – cottage and bungalow, for example Nouns High in the hierarchy, the senses (denotations) of words are rather general and undetailed, which has the consequence that these words denote many different kinds of entities At successively lower levels, the meanings are more detailed, denoting narrower ranges of things Nouns The meaning of a hyponym can be seen as the meaning of its immediate superordinate elaborated by a modifier So the meaning of house is the meaning of building modified, in this case by the modifier ‘for living in’ Nouns Because building is itself a hyponym one level below structure, its meaning can be seen as that of a structure plus a modifier, ‘with walls and a roof’ Nouns Hyponymy and the has-relation These two semantic relations should not be confused Hyponymy is about categories being grouped under superordinate terms But the has-relation concerns parts that prototypical members of categories have Nouns There is nonetheless a link between the two relations Hyponyms ‘inherit’ the parts that their superordinates have If a prototype superordinate has certain parts then prototype members of that superordinate’s hyponyms also have those parts Nouns For example, a prototypical tool has a handle, and prototypical members of hyponyms of tool have handles too, by inheritance Prototypical saws have handles Prototypical garden tools have handles – rakes and hoes Nouns Prototypical kitchen tools have handles – spatulas and egg whisks A non-prototypical kitchen tool, such as a mixing bowl, need not have a handle The inheritance passes down through hyponymy Nouns Incompatibility Breakfast, lunch, and dinner are hyponyms of meal, their immediate superordinate word Hyponymy guarantees that if we hear that some people have breakfast in Bakersfield, then we know they had a meal in Bakersfield Nouns Breakfast is one kind of meal However, there is no similarly straight entailment from a sentence with the superordinate – from a sentence containing meal to the corresponding sentence with one of its hyponyms Nouns If we are told that some people has a meal in Bakersfield, we cannot conclude, just from that, that they had breakfast there It might have been lunch or dinner So what is the relation between hyponyms like breakfast, lunch and dinner? Nouns A semantic relation called incompatibility holds between the hyponyms of a given superordinate Hyponymy is about classification Breakfast, lunch and dinner are kinds of meals Incompatibility is about contrast Nouns Breakfast, lunch and dinner are different from each other within the category of meals, since they are eaten at different times of day Here are the patterns of entailment Nouns 12) This is Fred’s breakfast 13) This is Fred’s lunch 14) This is Fred’s dinner 15) (12 NOT13) & (12 NOT14) & (13 NOT12) & (13 NOT14) & (14 NOT12) & (14 NOT13) If one of these sentences is true, the other two cannot be true Nouns On the other hand: 16) (NOT12 13) & (NOT12 14) & (NOT13 12) & (NOT13 14) & (NOT14 12) & (NOT14 13) A comparable set of entailments is not available from negative versions of the sentences Nouns Knowing that Fred did not eat breakfast does not allow you to know that he ate lunch – it might be dinner Hyponyms of a word immediately superordinate to them are not only incompatible with each other, but are also incompatible with hyponyms of their higher-level superordinates Summary/Minute Paper: Nouns Superordinate Hyponyms Drinking vessel glass, cup, mug Glass wine glass, martini glass, tumbler Cup coffee cup, tea cup Mug coffee mug, beer mug Nouns A tea cup is not only not a coffee cup or any other kind of cup It is also not a glass or a mug nor any of the hyponyms of glass or mug