Stoves & Patents

advertisement

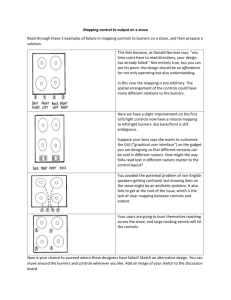

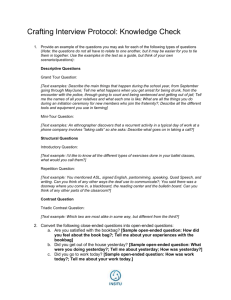

Stoves & Patents [working title only] One of the many interesting things about the stove industry – and something I’m only just beginning to work out – is how important patents were in the course of its development, how large they bulked in its history, and also how significant a role the stove industry played in the American patent system from the 1830s on. (The only novel about the industry of which I know, Robert R. Updegraff’s Captains in Conflict [1927], uses patent disputes and skulduggery as plot-devices in a way that informed readers would have found quite credible.) The reason I’m surprised is that, on the face of it, solid-fuel cooking and heating stoves, and the industry making them, don’t seem to be likely candidates for having been a key focus of Americans’ inventive activities, despite the obvious importance of these key domestic technologies. No new or fundamental scientific discoveries were embodied in them. There were no great breakthroughs. Progress was incremental, from the 1830s until at least the 1870s, by which time the products were ‘mature’ and the rates of change and improvement declined. And the industry itself included no very large firms to direct and exploit the inventive process. Whatever their makers may have said to the contrary, stoves were also actually remarkably like one another, as manufacturers settled on a few key principles of workable design in the 1830s after an early phase of experimentation while makers (and consumers) were finding out what constituted a serviceable product. One might, perhaps, therefore have expected the industry to be an example of what the economic historian Robert Allen has called “collective invention” – the development of techniques and products as a result of a series of ‘micro-inventions’ freely shared with one another by members of entrepreneurial communities more impressed by the advantages of playing cooperative positive-sum games among themselves than by resorting to the questionable and costly attractions of the patent system.1 Nothing could have been further from the truth. Collective invention there certainly was, among a community of stove-manufacturers who were intensely aware of what their fellows (competitors, neighbours) were doing, and paid the inventors of useful or marketable improvements the dubious honour of plagiarism, piracy, or near-imitation that came as close to copying as the law might permit. The resulting stove patent infringement cases were very confusing, because outsiders (e.g. lawyers and judges) sometimes could not understand what all the fuss was about, or what the key patentable features of a disputed product or design really were. Were they at all useful? Were they even novel?2 Robert C. Allen, “Collective Invention,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 4 (1983): 124. 2 See e.g. Howard et al. v. Detroit Stove Works, 150 US 64 (1893) – the one stove patent case that made it to the Supreme Court, pitting two great Michigan firms, the Round Oak Stove Co. of Dowagiac and Detroit Stove, against one another. 1 1 But stove patent cases were also numerous, costly, and bitterly-fought. This was because the industry, from its very beginnings, was addicted to the patent system. Stove inventors, entrepreneurs, designers, and makers – overlapping categories – were confident enough that they could use it in order to capture the added value they claimed that their discoveries made possible, or in order to give themselves and their products an edge, some distinctiveness, in a crowded, competitive marketplace, that they struggled with one another to establish and defend their intellectual property rights in stove features, designs, and methods of manufacture. There were, it seemed, at least two ways of making money in the stove industry: by making and selling stoves; and by devising, patenting, assigning, and litigating over inventions and designs. In a very competitive marketplace, it was not clear which route would pay off best, so both were explored energetically. *** First, the facts: comparatively speaking, how active and prominent was the stove industry in seeking legal defences for its inventions and designs? It makes sense to answer this question in three stages, the first running through 1836, the second overlapping slightly, and running from 1830 through 1873, the third running from the 1870s through (for the moment) 1920. Why 1836 as a first cut-off point? Because the U.S. Patent Office burnt down in that year, leading to mass destruction of the historical record which was only partly (about 40 percent) salvaged or reconstituted thereafter. As a result, the record is a lot thinner for the pre-1836 period and, as a practical matter, there was a new legal regime after 1836, and two discontinuous sequences of patent records. Why 1873 as a second cut-off? The main reason is again practical – that was the end-date of the U.S. Patent Office’s Index of Patents Issued from the United States Patent Office from 1790 to 1873, Inclusive whose digital publication by Paratext™ as part of their 19th Century Masterfile has done so much to facilitate this research. But one could also argue that the 1870s was a crucial period in the stove industry’s development – one where the rate of significant innovation declined (this was certainly the opinion of the industry’s best-informed historian, William J. Keep, a stove inventor himself), and manufacturers turned away from the law of patents to other techniques (collusion, brand-name development, the trade-mark system, advertising, product diversification, and other forms of non-price competition) in order to try to protect themselves from some of the consequences of producing a commodity product in a competitive national market. Why 1920 as a final cutoff? Because, though the solid-fuel cooking and heating appliance industry continued into the interwar period, it was by then marginal and moribund. Inventive activity was negligible, had indeed been in sharp decline even before the First World War. New fuels or heat sources – gasoline and kerosene, gas, both manufactured and 2 natural, and electricity – powered the appliances in which inventive activity continued apace. 3 Chart 1: Stove-industry patents (a) as a percentage of all patents (solid blue line, LH axis) and (b) annual totals (dotted red line, RH axis), 1805-1836 16% 80 Stoves%All 14% 70 Stoves 12% 60 10% 50 8% 40 6% 30 4% 20 2% 10 0% 0 1805 1810 1815 1820 1825 1830 1835 What can we see from the above summary chart? That there was a steady trickle of patents relating to improved cooking and heating apparatus, and means of making it, from 1805 onwards (before then, such patents were few and very occasional), but through the end of the 1820s the numbers are small, the proportions modest, and the significance limited. Americans in the New England and Mid-Atlantic states were beginning to get used to making and using stoves, and were experimenting with their improvement; but there were no centres of production and invention, very few repeat patentees (i.e. specialized inventor-entrepreneurs – key figures in C19th economic development), and the process of turning practical knowledge into intellectual property was quite underdeveloped. There was no community of stove inventors, little communication among them (and thus much unconscious imitation, as well as the exploration of what would turn out to be wackily alternative, rapidly abandoned paths towards the design of a serviceable stove), and little capacity for inventors to turn ideas into profit because the making of stoves was small-scale and thoroughly decentralized, and markets were narrow. Prototypes of functional cooking stoves were developed – William T. James of Union Village (later Lansingburgh), New York’s famous ‘saddlebag’ design of 1815 (patent X2296) and Christopher Hoxie of Hudson, New York’s, large oven with downdraft flues of 1816 (patent X2586). These stoves were made and sold in comparatively large numbers for the next decade and more, their inventors adding small improvements (James’s sunken hearth of 1824, number X3854), and licensing manufacture to small furnace-operators in the Hudson Valley region. But their impact was strictly limited: Hoxie’s innovations, in particular, would have to be independently rediscovered in the 1830s by a subsequent generation, and if it had not been for a bitter patent dispute in the 1850s, which resulted in the gathering of wonderful testimony on the 4 embryonic Hudson Valley stove industry of the 1820s, they might have remained forgotten. (Neither James’s nor Hoxie’s patents survived the 1836 fire. James ‘saddlebag’ stoves survive in museum collections to this day, but even by the 1850s no Hoxie stoves were thought to exist – their owners had all replaced them with more modern equipment, and sold them for scrap. Hoxie was a frequent patentee, but generally for farmingrelated inventions – his stove was a one-off.) There is just one crucial but partial exception to the above account of the lack of professional invention in the stove industry before the 1830s: Dr Eliphalet Nott, president of Union College, Schenectady, political operator, speculator, and the man usually credited with developing an effective way of burning America’s new wonder fuel of the 1820s – Pennsylvania anthracite, the answer to the East Coast’s emerging fuel crisis; though in fact there were numerous other investigators working at the same time. Nott, with 29 patents and renewals to his credit, 1819-1839 (one, in 1819, for a fireplace, X3064; four in 1826-1828 on the evolution and management of heat, X4477, X4622, X4772, and X5048; and then for a succession of anthracite-fuelled heating and cooking appliances, 18321839 applying his research findings, which were produced and sold in large numbers in an Albany foundry formally operated by his son, as well as by other makers who paid him royalties), certainly fits the picture of a professional inventor, though even his most creative period falls in the early 1830s, not the 1820s. He was scientifically literate, empirical, experimental, entrepreneurial, and an effective self-promoter, all at the same time. He was not the only repeat patentee in this early or transitional period, but he was certainly the best known, the most focused and prolific, and probably the most influential, not least for his example – he made big money from his inventions; and where he led, many other Hudson Valley stovemakers soon followed. The big change in the time series is clear to see: the early 1830s, when Nott and others were developing serviceable anthracite-burning appliances, and ‘practical stovemakers’ like Jordan Mott of New York – himself a repeat patentee, losing his stove virginity with X4589 in 1826, but following that with a dozen more, 1832-1838 – and Joel Rathbone of Albany transformed the way they were made and sold. There is no space to go into this in detail now, but the key changes were (1) the introduction of the cupola furnace, itself anthracite-fuelled, permitting the movement of stoveplate manufacture from the rural, mostly charcoal iron, furnace, to any urban centre with good transportation for fuel, flux (limestone), and raw material (pig iron and scrap), and advantageous market access; (2) the progressive abandonment of open-sand floor moulding for flask moulding, permitting thinner, lighter plates, more elaborate decoration, and rounded rather than near-flat shapes; and (3) the redesign of products, and the development of manufacturing techniques, enabling stove manufacture to make the transition from custom or very small batch-production to largebatch, repetition production. The incentive for all of these innovations, of course, depended on the availability of a large and growing market for 5 stoves, so that one could argue that the key date, underlying all others, is 1827 -- the completion of the Erie Canal which, together with the Hudson River, the Champlain canal, and the Delaware & Hudson canal, opened up access to fuel and raw material sources and western markets alike, permitting the establishment of the Hudson-Mohawk stove making district which would turn into the key national centre of innovation thereafter. As Chart 2 shows, American stove-inventors went patent-crazy in the 1830s, just at the time when the young industry was booming, and key innovations underlying the subsequent development of serviceable products to satisfy a hungry market were being made. Henry Stanley of Poultney, Vermont’s circular-hearth stove of 1832, X7333, improved by X9282 in 1835, 91 [new series] 1836, and 4,238 in 1845; Darius Buck of Albany’s large-oven, downdraft-flue range of 1839, reinventing Hoxie’s principles, number 1,157, improved by number 5,967 in 1848, renewed and reissued in the early 1850s, and defended in vigorous litigation for years after his death by his determined widow Désirée; Philo Penfield Stewart of Oberlin and then Troy’s X8275 (1834) and 915 (1838), the foundation patents for a string of improvements, reissues, and extensions through 1865 on which Fuller & Warren, Troy’s largest stovemaker’s product line would come to depend – these were the key innovations, licensed to other makers, imitated, pirated, and improved on over the following decades. 6 Chart Two: Stove Industry Patents, 1830-1873 12% 500 450 10% 400 STO 350 8% Paratext 6% 300 250 Total 200 4% 150 100 2% 50 0% 0 1830 1835 1840 1845 1850 1855 1860 1865 1870 Explanation: I have two not-quite-compatible databases of stove patents, one compiled from Paratext™’s digitized version of the 1873 Patent Office index, the other from Source Translation and Optimization™’s guide to all US patents for invention, 1836-1995. STO’s data is in some ways more useful than Paratext™’s – it distinguishes clearly between original patents and extensions/reissues, and it classifies patents according to current PTO standards; the information underlying the dotted blue time-series is thus “all original patents in Class 126, Heating & Cooking Apparatus” whereas the Paratext™ database used 1873’s crude, confusing, and outdated classification system, so stove-industry patents had to be identified by keyword searching rather than relying on it. It is clear, however, that the two processes have produced essentially the same result. Both of these time-series are charted against the LH axis, and show stove-industry patents as a proportion of the annual national total. The other time series, “Total,” charted against the RH axis, shows the number of stove patents per year according to the Paratext™ series -- not especially revealing, though it’s typically pro-cyclical (i.e. inventive activity peaks in years of intense economic boom) and demonstrates very graphically the furious competition for diminishing returns in intellectual property rights during the post-Civil War decade. Note, too, the way in which patents for invention diminish in number, as design patents (see below) become available, 1843-, as an alternative or complementary way of establishing product differentiation and a non-price competitive position. What the chart shows is the great surge in inventive activity (as recorded by patenting) in the stove industry from the mid-1830s through the mid1850s, by which time the industry’s key products – solid-fuel cooking stoves and ranges, room heaters (including those working on the “baseburning” principle perfected in the 1850s), and hot-air furnaces – all existed in recognizably the same form as they would continue to have until their large-scale production ceased almost a century later. The STO- 7 derived database allows one to see where all of this inventive activity was focused: Table 1: Classification of Stove Industry patents, 1836-1873 [Source: STO Database – Original Patents Only] Percentage Cumulative Total STOVES, COOKING 29.1% STOVE LIDS & TOPS 3.2% 32.3% OVENS 1.8% 34.1% STOVE DOORS & WINDOWS 2.0% 36.1% STOVES, HEATING 17.3% 53.4% HOT-AIR FURNACES 11.9% 65.3% FIRE POTS 4.9% 70.2% DAMPERS 5.6% 75.8% GRATES 10.4% 86.2% FIREPLACES 6.4% 92.6% As we can see, more than a third of patents focused on the key appliance itself (the cooking stove) or significant features of it – the cooking surface, ovens, doors and windows, which allowed bright firelight into the gloom of the pre-gas, even pre-kerosene-lit household. The latter small category of improvements also affected the next major appliance-group, heating stoves, where it was even more important than in the kitchen that the stove should make the parlour light as well as warm on winter evenings. Hot-air furnaces were comparatively expensive, only suitable for houses or public and commercial buildings with basements, and required costly internal structural modifications to make them work (installation of hot-air ducts, register-plates, etc.) But they were powerful, economical, and efficient, and there was a strong urban and middle-class demand for them. Fire pots and grates are the crucial and problematic heart of any solid-fuelled appliance: innovation there focused on making them durable, convenient (minimizing the need for manual poking and ash- and cindersifting, maximizing the length of time for which a stove could burn if occasionally refuelled), safe, and economical. Dampers received plenty of attention, because they were the means by which stoves were regulated. Maximizing controllability and economy, and minimizing smoke and fumes in the room, depended on getting them right. Fireplaces received a limited amount of inventors’ attention, even though they had become marginal to the tasks of keeping most American homes warm. There was a continuing middle-class, particularly urban demand for their cosy and nostalgic presence (one could afford the waste of an open fire, if one already had furnace or boiler heat), so inventors attempted to make them, too, more efficient, more economical, and more convenient – aspects of heating appliances American consumers had learned to expect. Inventive activity in the stove industry was not simply focused on the three main appliance-groups (stoves and ranges, heaters, and furnaces) and features common to all of them (fire-pots, dampers, grates); it was also geographically concentrated, just as the industry itself became as it 8 grew. In the late 1820s and early 1830s there were few repeat inventors or professional patentees closely attached to the industry itself; by the 1840s there were legions, by the 1850s armies, by the 1860s hordes. And the largest number of them lived in the two small industrial cities of Albany and Troy, New York, together with their surrounding and dependent villages and towns (particularly Green Island, Cohoes, Lansingburgh, and Watervliet). Other “working documents” on this site illustrate the New York Capital District’s importance to the stove industry in terms of production; but there is a similar, indeed a bigger, story to tell in terms of innovation. Table 2: Geographical Concentration of Stove-Industry Patents, 17901873, by State [Source: at the moment very crude – all of the patent records – for invention, design, reissues, disclaimers, etc., in the Paratext™ digitized version of the 1873 Patent Office index. Non-US patents have been omitted – only the Canadian are British are in double figures.] State Patents Percent Cumulative New York 2,559 39.5% Pennsylvania 963 14.8% 54.3% Massachusetts 645 9.9% 64.3% Ohio 547 8.4% 72.7% Illinois 233 3.6% 76.3% Connecticut 164 2.5% 78.8% Maryland 149 2.3% 81.1% New Jersey 132 2.0% 83.1% Wisconsin 117 1.8% 84.9% Missouri 110 1.7% 86.6% Table 3: Geographical Concentration of Stove-Industry Patents, 17901873, by City Troy Philadelphia Albany New York Cincinnati Boston Brooklyn Baltimore Chicago Rochester NY PA NY NY OH MA NY MD IL NY Patents Percent. Cumulative 663 10.2% 615 9.5% 19.7% 509 7.8% 27.6% 505 7.8% 35.3% 297 4.6% 39.9% 265 4.1% 44.0% 124 1.9% 45.9% 121 1.9% 47.8% 95 1.5% 49.3% 95 1.5% 50.7% 9 As we can see, these ten towns and cities between them were responsible for fractionally above half of all stove patents in this whole period, with Troy, the smallest among them, leading the way. The New York Capital District as a whole, with 1,315 patents, outpunched Philadelphia and NewYork-Brooklyn, the United States’s two largest and most diversified manufacturing metropolises, rolled together; at least in terms of inventive activity. This is a much larger measure of the Capital District’s importance (roughly double) than the 1874 production figures might have led one to expect. When did the Capital District come to focus so obsessively, and productively, on stove patenting? Chart 3: Inventive Activity in the New York Capital District: Stove Patents (Black) and All Others (Gray) 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 1800 1805 1810 1815 1820 1825 1830 1835 1840 1845 1850 1855 1860 1865 1870 1875 The answer is clear enough: despite Eliphalet Nott, Darius Buck, Philo Stewart, and others’ early contributions in the 1830s, the real stovepatent craze only begins in the mid-1840s. Stove patents made up more than half of the area total in 1832 (60 percent) and again in 1835 (53 percent), but the numbers themselves are unimpressive – 3 of 5, 9 of 17. From the mid-1840s, on the other hand, both the numbers of patents and the proportions of stove patents grow markedly, so that for the entire decade, 1845-1854, more than half of all patents filed in the district were for stoves in one shape or form – stoves, ranges, heaters, and furnaces themselves, ancillary appliances to make them more effective, and ways of batch-producing them more efficiently. How are we to explain this – not just the timing of the stove boom, but also the district’s national pre-eminence, and particularly Troy’s within it? There must be many reasons, some of them having to do with the normal “agglomeration economies” of an industrial district. In other towns and cities across the United States, including New York and Philadelphia, stove 10 manufacture was just one industry among many [See Table 4]; in Albany, and even more particularly Troy, it was the main focus of entrepreneurial effort for a two-generation period. This meant that Albany and Troy were places where ambitious iron moulders, foremen, pattern makers, superintendents, manufacturers, and just plain people with a good idea for improving a stove, were most likely to encounter like-minded fellows (and potential customers or business opportunities), and to be familiar with how to go through the process from idea to prototype to patent to exploitation. They would find experienced model-builders, patent agents and attorneys to assist them, counsel and expert witnesses to stand by them in litigation. To apply a rather desperate analogy, the New York Capital District was the Cast-Iron Valley of the solid-fuel heating revolution of the mid-19th century. Table 4: Keyword Count: Philadelphia and New York Capital District Patent Records Compared, 1790-1873 KEYWORD PHILADELPHIA Phil% Rank STOVE COOK STEAM COAL RAIL IRON HEAT WATER FURNACE FIRE CAST MOLD GAS BOILER SEWING WASH RANGE ANTHRACITE STEEL TELEGRAPH Totals 447 178 382 74 274 164 132 177 132 137 70 65 214 135 150 79 58 7 54 23 8,486 5.3% 2.1% 4.5% 0.9% 3.2% 1.9% 1.6% 2.1% 1.6% 1.6% 0.8% 0.8% 2.5% 1.6% 1.8% 0.9% 0.7% 0.1% 0.6% 0.3% 1 5 2 14 3 7 11 6 12 9 15 16 4 10 8 13 17 20 18 19 CAPITAL DISTRICT 1,153 440 87 79 75 75 73 63 53 51 48 37 33 31 29 26 26 18 8 8 3,546 AST% Rank 32.5% 12.4% 2.5% 2.2% 2.1% 2.1% 2.1% 1.8% 1.5% 1.4% 1.4% 1.0% 0.9% 0.9% 0.8% 0.7% 0.7% 0.5% 0.2% 0.2% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Diff 3 -1 10 -2 1 4 -2 3 -1 4 4 -9 -4 -7 -3 2 -1 -1 Explanation: What I’ve done is simply to do a keyword count on all Philadelphia (8,486) and Capital District (3,546) patent records, which produces suggestive results about the relative prominence of stove inventors and inventions in the industry’s largest centres. (New York City is a bit too much to chew yet.) As one can see, “stove” is the most frequently-occurring keyword in both places, but in the Capital District it, and the words most closely associated with it (cook, heat, and particularly coal), rank much higher. In Philadelphia, a diverse manufacturing metropolis, the stove industry was one among many; in the Capital 11 District, it was overwhelmingly dominant, defining the landscape for the entrepreneurial inventive community. It’s worth, in passing, looking at the keywords where there’s the largest rank difference in Philadelphia’s favour. “Gas” is the outstanding difference. At this stage, gas – for illuminating and cooking – was an exclusively urban fuel. Apparatus for making, transforming, metering, and using it preoccupied a significant number of Philadelphia inventors and companies; the Capital District was wedded to solid-fuel, hence the fact that “coal” (usually “coal stove”) ranks 10 places higher than in Philadelphia, the ruler of Anthracite District. *** But there is another reason too. It relates to the stove industry’s very distinctive encounter with the US Patent System, which is connected in turn to the peculiarities of the stove as a product and the means of its manufacture. There was more than one kind of patent that mid-19th century entrepreneurs could seek, giving them a theoretically exclusive right to use, sell, or licence their intellectual property for a period of years. There were patents for inventions, and from 1842 there were patents for designs too. Stoves – particularly cooking and heating stoves – appealed to consumers because of what they did, and how well they performed, but also because of how they looked. They were items of domestic furniture as well as objects of utility. The beauty, if I can use that word, of the way in which they were manufactured (the material from which they were made, the processes employed) is that it permitted manufacturers to deal to some extent separately with the stove’s internal working arrangements and its external appearance, and to attempt to distinguish their products from other manufacturers’ in both key respects. The patent system always allowed protection for (and therefore provided an incentive to) innovation in functional design, but from 1842 onwards it also gave a limited protection to what stove makers termed a stove’s “dress.” And pattern-makers and moulders had by this time become expert in exploiting to the full the potential that wood carving and iron moulding provided for turning stoves into extraordinarily decorated as well as decorative objects. The stove industry, already booming in the late 1830s, then meeting hard times in the mid 1840s, turned quickly to the possibilities of the designpatent system as a way of continuing to carry on their furiously competitive elaboration of the stove’s external appearance, their cultivation of what they and their customers thought of as its aesthetic value – and at the same time gaining a limited property right in the resulting designs. This meant that, just as with innovations in functional design, stove makers who devised something giving their products an edge in the market would be protected against their competitors, or would be able to add to the profits in making and selling stoves with the trade in intellectual property rights in designs, by sale or lease. 12 Stove manufacturers made the design patent system very much their own. The promise of the invention patent system for conveying secure intellectual property rights and competitive advantage to stove makers had already begun to prove disappointing by the late 1840s – because it was so hard and costly to prove priority and to manage IPR against determined opponents who were prepared to stretch or break the law, and to pay for the consequences as the price of doing a profitable business. Design patents provided a substitute and/or a complementary means to secure a temporarily protected market position or to squeeze revenue from one’s competitors as the price of permitting them lawfully to imitate a winning design. Chart 4: Stove Industry Design Patents (LH axis) and Share of ALL Design Patents (RH axis), 1843-1873 100 100% 90 90% 80 80% 70 70% 60 60% 50 50% 40 40% 30 30% Stove Design Patents Stove % Design Patents 20 20% 10 10% 0 0% 1843 1848 1853 1858 1863 1868 1873 As we can see, stove manufacturers took to the design patent system like ducks to water; it might almost have been designed (sic) to meet their needs. Producers of other domestic goods were slow to jump on the bandwagon, so that through the 1850s more than half of all design patents taken out in the United States were for stoves – in the late 1840searly 1850s, well over two-thirds. Patents for design, like those for invention, were strongly pro-cyclical: when the market was depressed, entrepreneurs did not invest in bringing out new products, concentrating instead on cutting costs, maintaining collections if possible, and expanding sales. It turns out that one of the key reasons for the New York Capital District’s pre-eminence in the stove manufacturing industry, with a record for innovative activity far in excess of its share of production, is that it served as the national centre for design innovation, rather than for functional improvements. Fifty-three percent of Albany and Troy’s stove-industry patents were for designs rather than “improvements,” as against a figure 13 of just 18 percent for the rest of the U.S; together, they contributed 38 percent of the national total of stove-industry design patents, as against just 11 percent for “improvements.” Designs Improvements Design % Albany & Troy 568 509 53% Others 915 4,286 18% A&T/All 38% 11% Close examination shows that the introduction of design patents created an almost entirely new group of multiple patent-applicants, who were barely engaged in seeking patents for invention, if at all. Albany and Troy pattern-makers and stove makers including Ransom, Vose, Gibbs, and particularly Ezra Ripley and Joel Rathbone all took out multiple design patents before 1850, whereas they had previously had little involvement with the system. Where they led, Dr Eliphalet Nott’s former chief patternmaker followed in the 1850s through 1870s. Nicholas Schwarz Vedder was the scion of an old local Dutch family, and active in the business since 1831, initially as a junior partner to Ripley, then on his own account. Vedder, “the prince of pattern-makers,” became the chief industrial designer to the entire industry. Unlike most of his immediate predecessors, he did not mix pattern-making with stove manufacture. Instead, he specialized, concentrating on design innovation and the creation of the wood and particularly the iron patterns on which batchproduction depended. The design patent system allowed and encouraged him to develop a trust relationship with the stove-manufacturers who depended on his abilities: he could sell them, not just attractive designs and the patterns needed in their manufacture, but the promise of exclusivity (at least a qualified exclusivity). They received an imperfect guarantee that, if they bought a good and expensive Vedder pattern, he would not sell it to their competitors too; and that, if the competitors rushed to imitate, there was some prospect of a recourse to law. Vedder turned into the most prolific repeat patentee in the entire industry, with 164 patents in his own name, 1851-1873, all but 11 of them for designs rather than inventions. So great was the commitment of Capital District pattern-makers and stove designers to the design patent system that, as the next chart in this research note indicates, by 1849 they were responsible for, not just 55 percent of stove industry patents, but 49 percent of ALL design patents in the entire U.S. They would never again have this share of the overall national total, but their industry dominance was sustained remarkably well – great year-to-year volatility masking a trend of only very gradual decline in their share of stove industry design patenting, even as the industry grew rapidly in the 1850s, more than doubled its output again in the 1860s, and the decisive move of production towards the mid-west began. 14 Chart 5: Capital District Stove Industry Share of (a) ALL US Design Patents (red column series) and (b) Stove Industry Design Patents (black line series, and trend) 60% % Total % Industry Trend 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1843 1848 1853 1858 1863 1868 1873 Finally, what about my Third Period, through the 1920s? This is as yet much less well-developed than any of the analysis of the pre-1873 records – all I have from STO are invention patent numbers, dates, and classes. It will be necessary to add to these by locating design patents (something now possible thanks to Google™ Patents), and by sampling original patent documents in order to add in the detail about patentees and locations, and also to do. But, even so, the data are quite suggestive. 15 Chart 6: Stove-Industry Invention Patents, 1830-1920: Absolute Stagnation, 1870-; Relative Decline; and the Collapse of Innovation in the Solid-Fuel Sector 11% 350 All Stove Patents 325 All Stoves as % All Patents 10% 300 9% 275 8% 250 225 7% 200 6% 175 5% 150 Solid-Fuel Stove, Heater & Furnace Patents 4% 125 100 Liquid- & Gas-Fuelled Stoves & Heaters & Electric Stoves 3% 2% 75 50 1% 25 0% 0 1830 1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1920 The above chart is perhaps too “busy” -- in Excel, the text labels were the same colour as the series they described, but I hope viewers can read this anyway. It extends the data presented in Chart 2 and demonstrates very graphically that the depression of the 1870s marked a turning-point in the industry’s history of involvement with the patenting process. As the chart title indicates, what we can see is (a) the continued relative decline in the cooking and heating appliance industry’s share of all US patents (black), from about 2 percent from 1850 through the mid-1870s, to a figure less than half that; (b) the absolute stagnation – the lack of any trend, but rather simply pro-cyclical variation – in the numbers of such patents (red); and (c) the challenge of new fuels. Year on year, from 1870 on, the numbers of solid-fuel patents (blue) in successive boom years are lower than in those preceding them, and recessional troughs are lower still; and there is a steady, inexorable rise in the number of patents applied for in order to exploit the new heat sources of petroleum, manufactured and natural gas, and finally electricity (green). Data – as yet incomplete – on production levels would help explain this: the numbers of solid-fuel appliances made and sold stagnated after the early 1870s too; the industry became afflicted with overcapacity, inadequate demand, and (or so manufacturers complained), a distressing lack of profits. This mature phase of the industry was hardly one to encourage continued investment in innovation, especially as market share slipped away towards new fuels or new heating systems (by steam and hot-water via radiators) even if the heat source remained coal-fired. 16 There may be an institutional explanation for the end of significant innovation, too – as well as the fact that the appliances had been essentially perfected, so that there was less room for improvement. Some contemporaries certainly believed this. Here’s the story: in the mid-1870s, seeking competitive advantage and, he argued, stability within the industry, one of its leading players, John Strong Perry, of Albany – co-founder and first president of the National Association of Stove Manufacturers, 1872 – surreptitiously bought up all controlling patents on one of the last major general-purpose innovations, the anticlinker grate. He then attempted to turn other manufacturers – his fellow members of NASM, and also his competitors – into his licensees. This would have been a source of both profit and influence for him, a way of underpinning his other moves to stabilize the industry and encourage cooperative behaviour. But his peers did not see things that way: they counter-organized to fight him in the courts, setting up the Anti-Clinker, later Equity Protective, Association to pool the costs of defensive test cases to break his patents. It outlived this crisis, and became institutionalized. A generation later, a subsequent NASM president, Lazard Kahn of Cincinnati, would complain that the EPA had done its work too well: in its determination to limit the ability of any manufacturer to establish a competitive edge over his peers either by establishing a monopoly on any particular patent, or by charging them excessive license fees, they had removed much of the incentive to innovate, and locked the industry into a pattern of imitative stagnation from which there would be no escape. [That’s enough to chew on for now. It’s obvious to me that I’m going to need to refine the databases, and do more discriminating searches and subtotalling operations – e.g. not just dealing with the entire 1836-73 period as one bloc, and not rolling all different kinds of patent record in together. I will also need to get deeper into individual patent records; gain more knowledge/understanding of the assignment system; etc. But it’s a start.] HJH, 2007 Sample Stove Patent Documents from Online Patent Libraries [When I compiled this list, in August 2006, there were two ways of accessing patent documents online – via the US Patent & Trademark Office, and via the European Patent Office. The former contains more data – notably useful, for my purposes, are the surviving pre-1836 patents and design patents – but is very clunky to use, requiring for example a particular plug-in TIFF reader; the latter is much easier, and delivers documents as standard PDFs; but both are limited by the lack of a search facility except for patent numbers, i.e. you have to know what you’re looking for from other sources, e.g. my Paratext and STO-derived databases, in order to find it. But now (2007) Google has solved this problem, giving rapid and direct access to all the records in the PTO 17 database, and adding a powerful word-search facility. There are some limitations in its service: the order in which results are displayed follows Google logic, not anything more ‘rational’ e.g. date. But speed, convenience, and searchability more than compensate.] Charles Postley of New York City’s Reservoir Cooking Stove, 26 Apr. 1815, no. X002297, is the earliest stove patent of which the US Patent & Trademarks Office appears to have an online copy. (To view USPTO files, follow onscreen instructions—click the Images button. You will also need a TIFF reader plugin – freely obtainable from suppliers listed here). Eliphalet Nott’s rotary grate patent X004368, 23 March 1826, is one of his great series of innovations in anthracite-burning technology in the 1820s. The text is missing – only the illustration survives. X007636, 29 June 1833, is another grate patent [sic] in a better state of preservation. Jordan L. Mott (New York City)’s first surviving stove patent, for an anthracite ‘magazine’ (self-feeding) stove, X007096, was dated 30 May 1832. Mott was one of the first stove foundrymen to melt his own iron from the pig using a cupola furnace, and pour his own stoveplate, thus revolutionizing the industry. He was also a prolific patentee, emphasizing the importance of designing products for economy of manufacture. Joel Rathbone of Albany’s Flat Cook Stove, patent X008677 of 6 Mar. 1835, is for a fairly typical elevated oven (step) stove, an obvious derivation or development from the original James ‘saddlebag’ patent; included here not because of any particular importance, but just as the first surviving Albany patent by one of the founders of the local industry, doing in Albany what Mott was doing in New York at the same time. Like Mott, he too went on to become a repeat patentee. X-type (pre-1836 Fire) patents only seem to be available from the US Patent & Trademarks Office website. About 40 percent of them seem to have survived, or to have been reconstructed after the fire – patentees were invited to resubmit copies of their work, something which was obviously in their interests. Main sequence (post-1836) invention patents are also obtainable from the European Patent Office, which is handier as they are supplied in PDF rather than TIFF form, requiring no special browser plugin. Henry Stanley of Poultney [sic], Vermont’s revolving-hearth cooking stove enjoyed passing importance in the 1830s. As with the plans of a number of early stove inventors, it is obvious that the principle underlying his patent was to make the stove analogous to the hearth it replaced. Inventors aimed to control cooking heat by moving the fire nearer to or further from the cooking pot. Some did this by raising and lowering the fire; Stanley and a few imitators or co-inventors moved the pot towards or away from the heat source by setting it into an offset turntable. Rotary stoves were heavy, had more moving parts to break down than regular stoves, and did not solve the problem of oven heat control and distribution. Stanley’s 28 November 1836 supplementary patent 91 does 18 not include a drawing; for which see the original of 17 Dec. 1832, X007333. Darius Buck’s 20 May 1839 Albany patent for a cooking stove, 0001157, is one of the most important in the development of the device, because what he (or Crowell, the man whose ideas he stole) had done had been to reinvent or ?independently rediscover or recover the lost Hoxie patent of 1816, X2586, which pointed towards the larger, more controllable heatdistributing oven that lay at the heart of the mature C19th product. Buck’s patent 0005967 of 12 December 1848, his last before his death, extended the breadth of his claims, which would in the mid-1850s force Giles Filley of the Excelsior Manufacturing Co., St Louis to challenge his executrix and her licensees, who were using them to attempt to secure a profitable monopoly. The first of Philo P. Stewart (co-founder of Oberlin College)’s many cooking stove patents, for the “Oberlin” of 1834 (X8275), does not seem to survive. In any case, his 915 of 12 Sept. 1838 (by which time he described himself as a “stove maker,” and had moved to New York) represents the first in his sequence of inventions improving stoves’ fuel economy and controllability. Ezra Ripley of Troy’s Design Patent No. 5, 15 July 1843, for the dolphinshaped column for a kind of parlor stove then fashionable, is not just one of the very first design patents, it’s also Ezra’s first of what would become a profitable sequence. (Design patents, unfortunately, don’t seem to be obtainable from the EPO, just the PTO). He had patented nothing since his stove pipe of 1836, X9341 (destroyed in the Great Fire); between 1843 and 1855 he would go on to obtain 26 more patents, all of them for design patents, assigned to the stove makers who had commissioned or bought them of him. Ripley was thus the pioneer in what became a considerable business in mid 19th-century Troy and, to a lesser extent, Albany. Samuel Pierce, also of Troy’s 1850 “Union of the States” cook stove design, No. 338, is interesting not simply because of what its patriotic name and sunburst motif suggests about upstate New York political opinion during the post-Mexican War crisis over the Wilmott Proviso, but also because it includes on the drawing the graphic consequence of the patent system’s legal requirement for stoves’ appearance – the patent date and owner (or, in this case, assignee – the local firm of Johnson, Cox, and Fuller)’s name was cast into the object. Planned obsolescence could trace its roots back to this: by the early 1870s, cast-in patent details had gone beyond being a legal requirement and a convenience for the customer in ordering replacement parts. Instead, by emphasizing that a stove – otherwise functionally indistinguishable from its predecessors – was an 1872 rather than an 1870 design, makers could hope to stimulate buyers to pick theirs in preference to an older model, and to discard a stove with an embarrassingly antique patent date, even if its performance was quite satisfactory. 19 I’ve also selected this example because the beautiful hand-drawn original is one of those in the collections of the Rensselaer County Historical Society, from which I have also chosen James Savage of Troy’s “New York & Erie Cook,” No. 451, of 13 April 1852. The side of the stove is decorated with charming pictures of the railroad, whose tracks had recently been completed. The fireplace heater version of the same decorative scheme was still in the Marcus Filley pattern stock 23 years later; it had been assigned to his predecessor in business at the Green Island Foundry, Morrison & Tibbets. Design No. 404 of 29 July 1851, for a cook stove (the “Fashion of Troy”) with a variant of the sunburst design motif, is important simply because it was Nicholas Vedder’s first recorded design patent – though he had already been in the pattern-making business for twenty years by then. There would go on to be another 153 such design patents over the next twenty years, making Vedder the industry’s most prolific and influential designer. Finally, I include 90,756 of 1 June 1869, by William J. Keep, of Troy, improved flues for a cooking stove, not because it’s especially attractive in appearance, or important (there is no assignment data with the patent, so I cannot know yet whether Keep managed to sell his idea to somebody, or whether it entered into production), but simply because it was Bill Keep’s very first. Keep, by then an old man, and retired from his superintendency of the Michigan Stove Co. (to which he had moved, from Troy, in the 1880s, after a bruising patent dispute with his employer), wrote a wonderful manuscript history of the American stove in 1915, in which he recorded that he was the one surviving personal link to the great Capital District stove inventors of the heroic period. He was educated at Union College in Schenectady, Eliphalet Nott’s institution (where the original manuscript is stored); he began his career at Fuller & Warren, as Philo Stewart’s assistant – it must have helped that his father, the Rev. John Keep, was a stalwart of Oberlin College, which Stewart had helped found -- and took over responsibility for development of the “P.P. Stewart” product line when Philo died, having already turned into one of the earliest brand names in his own lifetime. 20