Getting to the Roots of Plant Evolution

advertisement

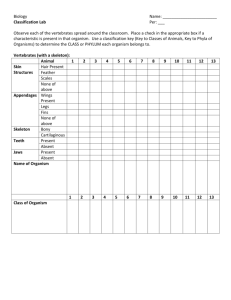

Getting to the Roots of Plant Evolution - Exercises Now that you know all about the characteristics of plants and how they made their move from fresh water to land, you can use this knowledge to reconstruct the evolutionary relationships of some plant groups that are alive today. In addition to the morphological characteristics, such as the cuticle and seeds that we discussed in the previous section, there are other types of characters present in the genomes of plants that can help us to understand their evolutionary relationships. While molecular characters such as these used to be very difficult to obtain, recent advances in fast, high volume DNA sequencing have made it possible to get large amounts of genetic sequence data for plants. One nice source of this sort of sequence data is the circular genome of the plant chloroplast, because it is smaller and more easily sequenced than the entire nuclear plant genome. And, because the chloroplast is a plant organelle, (having been derived from a bacterial endosymbiont), its genome does not undergo recombination; this makes reconstructing evolutionary relationships much less complicated, because each genetic trait in the chloroplast can be traced directly back (in time) through a lineage of mothers and daughters. On the next page, you’ll find a selection of schematics representing various chloroplast genomes and their arrangements for several groups of plants. These representations of the chloroplast genome show the positions of several genes (A-E) as well as the position of a distinctive region known as the inverted repeat. Genome-level characters such as gene position and structural rearrangements are very useful for reconstructing deep evolutionary relationships, because they are believed to occur fairly infrequently; it is unlikely that two groups of plants would have the same unique gene rearrangement due to chance alone. With this genomic information and all you learned about land plants in the previous section, you will be able to complete the land plant data matrix and use it to construct a cladogram (for a refresher on how to turn a data matrix into a cladogram, see the Cladisticules exercise, especially its Teacher Guide). Phylogenetic Analysis of the Green Plants Data Matrix 1 inv. repeat absent (0) present (1) green algae liverworts mosses lycophytes ferns gymnosperms angiosperms 2 inv. gene position no (0) yes (1) 3 4 5 6 cuticle absent (0) present (1) stomata absent (0) present (1) xylem & phloem absent (0) present (1) megaphyll absent (0) present (1) 7 sporophyte domin. no (0) yes (1) 8 9 seed absent (0) present (1) flower absent (0) present (1) Phylogenetic Analysis of the Green Plants Data Matrix (Solution) 1 inv. repeat absent (0) present (1) 2 inv. gene position no (0) yes (1) 3 4 5 6 cuticle absent (0) present (1) stomata absent (0) present (1) xylem & phloem absent (0) present (1) megaphyll absent (0) present (1) 7 sporophyte domin. no (0) yes (1) 8 9 seed absent (0) present (1) flower absent (0) present (1) green algae 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 liverworts 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 mosses 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 lycophytes 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 ferns 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 gymnosperms 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 angiosperms 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Questions for discussion 1) Contrast a seed plant to an alga in terms of adaptation for life on land versus water. 2) What evidence is there to support a charophyte ancestry for plants? 3) Bryophytes and vascular plants share a number of characteristics that distinguish them from charophytes and that adapt them for existence on land. What are those characteristics? 4) What is coal? How was it formed? What plants were involved in its formation? 5) What is a seed, and why was the evolution of the seed such an important innovation for plants? 6) How do the mechanisms by which sperm reach the egg differ between gymnosperms and seedless vascular plants? 7) Why was the flower such an important innovation? 8) What role do insects, animals and wind play in plant reproduction?