Part 2:Designing Instructional Illustrations

Part 2:

Designing Instructional Illustrations

The following section will provide some basic principles for instructors or training developers to follow in designing or choosing illustrations for use in their instruction.They will be helpful whether you are sketching illustrations on a whiteboard or transparency, designing your own computer graphic, or requesting work from professional illustrators. The principles are first listed, then each is elaborated upon with a rationale.

1.

The complexity of the illustration is reduced to the minimum level necessary for the objectives by eliminating unnecessary elements.

2.

Elements are appropriately grouped. The number of individual elements in groups is limited.

3.

Critical elements are made conspicuous, non-critical elements are de-emphasized.

4.

The illustration is organized to reflect the conceptual or real-world organization of the information.

5.

The figure stands out from the background.

6.

Interaction with the illustration is encouraged through the use of captions or questions and references in the text.

7.

Pictorial elements and words complement each other.

8.

The illustration is placed near the text that refers to it.

9.

The illustration has been tested with subjects representative of the intended audience.

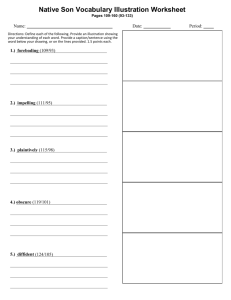

1. The complexity of the illustration is reduced to the minimum level necessary for the objectives by eliminating unnecessary elements.

One of the benefits of using illustrations is that their complexity draws the attention of students. However, there is a threshold beyond which complexity loses its benefits. More often than not, an illustration could benefit from a reduction in complexity.

We attend to only a small portion of the messages available to us. Our perception is selective, partly influenced by cultural and personal predisposition and intellectual background, but primarily due to the limited physical capacity of our senses (Winn &

Holliday, 1982).

Because students will see and hear only a selection of the sights and sounds presented to them, and because it is difficult to determine which of those sights and sounds they will attend to, instructors should be careful to control the complexity of illustrations. The

important elements should not be obscured by extraneous ones or by the sheer number of elements.

The simplest way to reduce complexity is to remove any elements that are not central to the message. Too often we let tradition, or even cliché, creep into illustration design, and it becomes difficult to recognize extraneous elements that seem to naturally belong. A little experimentation will usually identify those elements that can be deleted with no impact on the central message.

Rather than attempt to teach all criteria of a young supercell storm at once, the objectives of this lesson were treated separately.

Likewise, the illustrations, although they use the same base art, highlight only the features pertinent for the objective at hand.

2. Elements are appropriately grouped. The number of individual elements in groups is limited.

Ostensibly, grouping is a way of showing the relationships of individual elements. But in one sense, grouping items is another way to reduce complexity. We generally try to avoid chaos, and will attempt to organize what we perceive if it is not already organized for us

(Fleming & Levie, 1978). We want our perceptions to make sense to us. This is why we see constellations in the sky, and why lists of almost anything are fascinating to us. If we don't want learners to come up with their own (possibly misleading) organization, our illustrations should carefully organize elements into appropriate groups.

The capacity of working memory, the part of our memory where conscious mental processing takes place, is very limited. Grouping items helps learners process information by allowing them to focus on smaller sets of information at any given time. If those groups do not exceed five to nine items (according to most research), the information will not exceed the capacity of working memory, and will be more easily processed. Grouping also can allow learners to treat related elements as a set, rather than as individual bits. In this way, they may be able to work with larger amounts of information.

Grouping also helps students recall information from long term memory by storing it in manageable "chunks" in the first place. If each chunk is labelled, recalling the label will help to recall the entire group.

We should analyze illustrations to determine if adequate cues are used to signal the relationship of related elements. Color-coding, size or typeface similarity, physical proximity, superordinate labelling, and surrounding boxes or circles are just a few of the ways to identify groups of related elements.

Colors are used to organize the labels of this complex diagram.

Items are grouped into three types of features to simplify the illustration a bit for the viewer.

3. Critical elements are made conspicuous, non-critical elements are de-emphasized.

Another way to reduce complexity is to make sure that elements that represent the criteria of a concept or components of a principle standout in some way. Non-critical elements should be eliminated if possible, but sometimes they are necessary to establish a context for the critical elements. Using bolder lines, color, or a higher level of detail are several ways to make sure critical elements are obvious.

The bottom graphic to the left uses a simple but effective strategy to highlight the elements important to the instructional objective. It uses yellow

(the only warm color in the image) to highlight the symbols for the physical elements represented as variables in the hydrological equation for determining outflow in a water basin.

4. The illustration is organized to reflect the conceptual or real-world organization of the information.

Organization entails more than grouping and highlighting critical elements. Visual organization should reveal the process, hierarchy, or spatial organization of the elements depicted. Examples of processes that are commonly represented graphically include cause and effect, cycles, decision trees, and chronologies. Lines and arrows connecting words or pictures are good at revealing the direction and sequence of a process.

At least in Western cultures, left-to-right and top-to-bottom positioning implies a sequence, sometimes even when it's unintended. Studies have shown (Winn and

Holliday, 1982) that illustrations with right-to-left sequences strongly frustrate learning.

Hierarchies are best shown in top-to-bottom format with lines or arrows showing links within the hierarchy, or the decreasing widths of boxes showing spans of control or definition.

If an illustration represents concrete objects or processes of concrete objects, the spatial arrangement of the names or pictures of those objects should reflect their real-world arrangement (Winn and Holliday, 1982). This adds to the concreteness of the illustration, which may aid retention.

Several strategies are at work to indicate how energy flows through a biological ecosystem.

Arrows show the path of energy flow.

The horizontal series of boxes reveal the hierarchy of the food chain. The decreasing heights of those boxes show the relative size of the group

(not to scale).

5. The figure stands out from the background.

The "figure" is that portion of an image that is perceived to be in the foreground. It is the element that commands attention, and therefore should be the critical element. The

"ground" is that part of the image that is perceived to be in the background. It should be as unimposing as possible and serve to accentuate the figure.

How do we ensure that the desired elements are perceived as figures? Higher complexity, sometimes introduced by the use of texture, increased detail, or three-dimensional shading, enhances the figural quality of an element. Color contrast also separates figure from ground, as long as the background color does not stand out more than the figure color (black and white are interchangeable as figure and ground because they are equally neutral). It is easiest to determine good figure/ground contrast by standing back from an illustration and judging its readability.

Black and white line drawings, in particular, can cause figure/ground problems because the elements receive equal treatment in most ways. "Closed" elements, those with complete outlines, will be percieved as "figure" (Fleming & Levie, 1978). Elements that have incomplete outlines, as if fading at the edges, will be perceived as ground.

The arrangement of English vowel sounds in this illustration mirrors their positions of articulation within the mouth.

6. Interaction with the illustration is encouraged through the use of captions or questions and references in the text.

Learners tend to avoid redundancy. Although illustrations may at first get attention, learners will focus on the more familiar medium (spoken or written words) and avoid studying illustrations if they consider them to be redundant (Winn and Holliday, 1982).

Consequently, illustrations should always be referred to within the lecture or text to encourage attention and to point out the pertinent information. Instructors should never assume that students will study illustrations just because they are there.

Asking questions about an illustration is the surest way to get students to interact with it.

If questions are used, they should cover all the important information presented. Learners may conclude that questions cover the important points and may focus only on that information covered in the questions (Winn and Holliday, 1982).

All details that might have been included on the ground or in the background sky have been ignored in this otherwise realistic diagram.

Other than the shadow on the ground, the storm cloud itself is the only element that is drawn in three dimensions.

7. Pictorial elements and words complement each other.

Dual-coding theory suggests that information is stored in memory in both verbal and visual forms (Paivio, 1971). This does not mean, however, that instruction should duplicate all information as visuals and lecture or text. As mentioned above, learners avoid redundancy and will conserve effort by attending to only one mode of delivery if they suspect nothing is to be gained by attending to others. Text should be included in illustrations to label items or steps of a process. We usually want students to build strong associations between items and their labels. Lengthy descriptions, however, will only distract from the power of the visual. Similarly, long text items in a list defeat the purpose of the illustrated list, which is to aid retention through grouping. List items should contain as few words as possible. They should cue larger amounts of verbal information, not present it in its entirety.

Words are used sparsely but effectively in this series of illustrations.

They collaborate with the accompanying

Have you ever been lucky enough to be in Denver,

Colorado during a winter snow storm created by "upslope" conditions?

What direction were the winds blowing during the heaviest snowfall?

Where were the highest snowfall totals?

8. The illustration is placed near the text that refers to it.

If we want students to make associations between the text and the illustration, they should be visible at the same time. Contiguity is one of the most powerful ways to stimulate learners to associate (Fleming & Levie, 1978). Even logically unrelated things can become strongly associated through contiguity. For example, contiguity in time is the basis of superstitious behavior.

It can be difficult to follow this principle due to the limited space on the printed page and, especially, on a computer display. But placing an illustration on a page following the associated text or requiring a lot of scrolling to find the associated graphic is one of the best ways to frustrate learning. One solution is to wrap text around the graphic. On the computer, you can sometimes allow the text to scroll while holding the illustration on screen in a separate area. In long passages, inserting illustrations at the point they are referenced also helps to break the text into logical units and gives visual variety to the eye

(see checklist item 1). If references to the illustration recur in a long sequence of text, it may be best to repeat the illustration for each separate reference. images to explain a process of precipitation formation.

This interface uses buttons to allow the learner to display a text description for one feature of the illustration at a time. In this way, the illustration is never separated from the text that supports it.

9. The illustration has been tested with subjects representative of the intended audience.

Illustration design, like instruction in general, is not an exact science. Going through this or as many other checklists as you like still does not ensure that the illustration is going to teach your learners what you intend. Any instruction needs to be evaluated before it can be assumed to be effective.

Find one or more subjects who are similar to your learners in their level of knowledge of and experience with the topic, and ask them to explain what the illustration is showing.

Provide a list of questions that you would expect them to be able to answer after studying

the illustration and the related material. Based on their responses, you should be able to diagnose problems with the illustration or determine possible improvements.

References

Fleming, M. & Levie, W. H. (1978) Instructional Message Design , Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Educational Technology Publication.

Paivio, A. (1971) Imagery and Verbal Processes , New York: Holt, Rinehart, and

Winston.

Winn, W. and Holliday, W. (1982) Design Principles for Diagrams and Charts, The

Technology of Text (Jonassen, D.H., Ed.), Volume 1, 277-299.