ADHD in Children & adolescents - Community Child Health Resources

advertisement

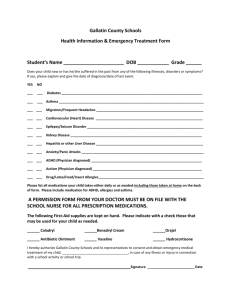

ADHD in Children & Adolescents – A Good Practice Guidance This guideline has been developed on behalf of the Executive Committee of the George Still Forum, the National Paediatric ADHD Network Group in the UK. It can be used by paediatricians, child & adolescent psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, nurses and other healthcare professionals working in the field of ADHD in the UK. Issue Date: 5 April 2011 Review Date: 4 April 2013 www.georgestillforum.co.uk 1 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Objectives of GSF 3 3. Incidence 4 4. Symptoms 4 5. Assessment and monitoring 4 6. Management 6 7. Other management options 12 8. Adolescents 12 9. Comorbidities 13 10. Cardiac risks of ADHD medications 15 11. Interventions 16 12. Treatment options 16 13. Management of some common problems 17 14. References 20 15. Appendix 1 Side effect questionnaire 22 16. Appendix 2 Care pathway 23 17. Appendix 3 Shared Care 24 18. GSF Executive Committee 26 2 1. INTRODUCTION George Still Forum is an apex organisation of the paediatricians, involved in assessment and monitoring of ADHD in children and adolescents. The group is recognised by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health as a special interest group. The aims of the forum are to exchange ideas, to increase professional awareness, to liaise with other professional groups, to influence public policy decisions where appropriate, to share information in relation to current issues in providing services to individuals and their families and to improve care for children and adolescents with ADHD. There is an increase in number of ADHD patients countrywide, highlighting the shortfall in resources and extended waiting times for the new assessments. This situation is posing an extra burden and is a threat to burn out amongst ADHD clinicians. George Still Forum aims to bring these issues to the notice of the commissioners in the National Health Service. 2. OBJECTIVES OF THE GSF To take a leadership role in managing ADHD in children and adolescents. To develop the ADHD guidelines for the Paediatricians in the UK. To facilitate development of training standards. To share information with the stakeholders. To advocate to NHS commissioners about ADHD. 3 3. INCIDENCE Estimates of the prevalence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) indicate that around 3 to 9% of school-aged children and adolescents would meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel-IV (DSM-IV) of American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic criteria for ADHD1. Follow-up studies of children with ADHD find that 15% still have the full diagnosis at 25 years, and a further 50% are in partial remission, with some symptoms associated with clinical and psychosocial impairments persisting2. 4. SYMPTOMS The three core symptom domains of ADHD are inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Subtypes of ADHD are diagnosed based on meeting the symptom thresholds according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of American Psychiatric Association3. The International Classification of Diseases of World Health Organization described this condition as hyperkinetic disorder4. The symptoms and subtypes of ADHD and associated comorbid disorders change through out the lifecycle. Hyperactivity and impulsivity may decrease as patients get older but the demands on their attention may increase. The Predominantly Inattentive Subtype may be more obvious by adulthood. 5. ASSESSMENT AND MONITORING ADHD is a chronic medical condition and needs a long term management plan5. ADHD patients deserve every opportunity to attain their full potential by having timely assessments to identify their impairments and to access the best management. Like other medical conditions in Child Psychiatry, ADHD is a clinical diagnosis for which there are no specific signs. It is diagnosed when parents/carers and school report overactivity, impulsivity and/or short attention span. It is therefore important to gather the information from parents/carers and school before arriving at the diagnosis. The observation of the child in a clinic setting is unlikely to rule out the diagnosis. ADHD can be provisionally diagnosed in preschool children but it should be confirmed after the child has started school. The initial assessment for ADHD should include: 5.1 Presenting Complaint A. Review with the parents of their concerns, the reason for referral, and the parents’ expectations from the assessment. Most often, a parent will come to discuss about hyperactivity, impulse control, inattentiveness or educational concerns. Parents should be asked about the pervasiveness of the symptoms. B. Review with the child/adolescent and parents/carers the completed rating scales. C. Interview with the child and parents/carers. D. Medical history and physical examination to ensure that there are no other medical causes for the symptoms of ADHD and to ensure that there are no medical contraindications to the possible use of medications. 5.2 Medical Assessment Medical assessment should include a perinatal and developmental history and a physical examination including neurological examination and for any contraindications for medication use, such as some cardiac dysrhythmias. Any abnormalities that are found in the physical examination should be followed by more detailed and specific tests. A history of sleep pattern as well as any preference to a fixed routine in daily life should be obtained. Vital signs of height, weight, blood pressure, and pulse rate should be documented and plotted on centile charts as baseline and during each follow-up visits if medication is prescribed. The following points should be included in the history during the initial assessment: 4 5.2.1 Antenatal History: o Antenatal infections (e.g., TORCH). o Smoking cigarettes, cannabis etc (how many a day, How often and how long?) o Exposure to drugs o Exposure to alcohol o High-risk pregnancy (e. g. premature delivery, LBW). o History of birth asphyxia. 5.2.2 Behavioural / Developmental History: o Early developmental milestones. o High activity level and difficulty engaging in quiet play. o Problems with obeying commands and oppositional behaviour. 5.2.3 Family History: o Parent or sibling with school failure. o Parent and/or sibling history of ADHD. o Drug or alcohol abuse. o Psychiatric illnesses. o Problems with the law. o Cardiac arrhythmias or sudden death especially in 35 years or younger age. 5.2.4 Home Environment: o Key caregivers. o Frequent moves? o Frequent changes in school? o Chaotic home environment? o Poor or crowded housing? o Excess (>2 hours/day) TV, computer, video games? 5.2.5 Peer Relationships: o Plays alone as has no friends. o Problems in maintaining friendships. 5.2.6 School History: o Academic under-achievement. o Truancy. o Does the child enjoy school? o Ask the school age child if he/she thinks he/she has trouble concentrating. o Review current school report as well as those from earlier years. o Specific Learning Difficulty (SLD; Dyslexia) is part of the differential and/or is comorbid with ADHD. Educational evaluation contributes to identification of SLD, learning strengths, under achievement relative to potential, impact of ADHD on learning and identification of processing speed, working memory and peer relationship skills. 5.2.7 Eating History: o Appetite. o Any dietary restrictions. o Skipping meals regularly. o Joins family members for dinner? 5 5.2.8 Physical examination It is important to document a baseline physical examination. Special attention should be paid to the following elements of the exam: o Growth parameters. Height and weight will need to be plotted on a centile chart as baseline and at each follow-up visit if the child is prescribed medication. o Blood pressure and pulse rate are recorded and plotted on the centile chart. o Cardiac examination including auscultation for murmurs and femoral pulses. o Dysmorphic features suggestive of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) or other genetic conditions. o Thyroid enlargement. o Cutaneous stigmata, such as café au lait spots. o Bruising or other evidence of injury (accidental or intentional). o Tonsillar hypertrophy, mouth breathing etc which may contribute to sleep apnea. o Neurologic exam and age-appropriate mental status exam. o Tics, either motor or vocal or both. o General behaviour: overall activity level, restlessness. o Observe the child/parent interaction. o Vision & Hearing screen (if indicated). 5.3 Cognitive Assessment The child should have a cognitive assessment in school preferably by an Education Psychologist for possibility of associated SLD. Academic achievements in key subjects are important as they may suggest the need for additional educational needs. 5.4 Emotional/Behavioural Assessment Assessment for any possible comorbid condition in the child is important. Input from the child’s teachers regarding his/her social, academic and emotional functioning is valuable as teacher/s can compare the child in the classroom setting compared to other pupils of same age range. 5.5 Feedback and Expectations Ensure that the patient and family have had an adequate opportunity to know about ADHD and various treatment options. They should be provided written information about ADHD and available option of various management strategies, website addresses, and contact details of the local support groups. Do ask the family to find out more about ADHD. Instruct the family to do some research on ADHD. Only proceed to feedback and treatment if the child has well documented evidence of impairment and meets the thresholds for ADHD, shows no other medical problems that would contraindicate further treatment and has parent(s)/carer(s) who are motivated. They need to know the symptoms that are being treated (no medication effectively eliminates all the symptoms of ADHD). There must be a discussion of the risks and benefits of the prescribed treatment and the alternatives. There needs to be discussion regarding potential risks of no treatment. Describe the key findings obtained from the assessment. Include a clear statement about the diagnosis and the basis on which the diagnosis is made. Explain to the family that you will be sending them a report and a copy made for the school, GP and other relevant agencies involved. 6. MANAGEMENT ADHD is a clinical diagnosis based on a combination of a reliable history, reports from home and school and a physical examination to rule out any other underlying medical conditions. Therefore it is important that symptoms be recorded using valid, reliable and sensitive rating scales to evaluate symptom frequency and severity. Rating scales are not diagnostic; they give information about a child’s current functioning and difficulties. Rating scales can also be used to monitor treatment efficacy and side effects. 6 6.1 Drugs Medications are to facilitate a holistic approach and are not a stand alone intervention. Discuss the drug treatment options. There is no one drug that is suitable for every patient. The guiding principle of drug intervention is to start in a low dosage and gradually increase it, though weightbased dosage may be used as a way of gauging adequate dosing. Parents should be informed that well controlled studies have shown medication to be safe and very effective in treating the symptoms of ADHD. In ADHD with comorbidity, multiple medications may be used. Start medication in low dosage and go slow but continue increasing the dose until maximum recommended dose level is reached or to where the target symptoms show improvement or the side effects appear. At the end of the visit, give the parent(s)/carer(s) the rating scale to be completed by parent(s)/carer(s), the rating scale to be completed by the class teacher and the side effect form that should be filled out by the parent(s)/carer(s) before medication is started and then every week. After establishing the diagnosis of ADHD with comorbidities if medication is considered then try stimulant if immediate response needed. If there is evidence of tics then non-stimulant is recommended. Similarly if there is need for late evening and early morning cover then nonstimulant medication may be tried. 6.3 Choice of medication The choice of medication will depend on the following factors: 1. Age 2. Duration of effect 3. The onset of action of the medication 4. Comorbid disorders 5. History of earlier medication use 6. Attitudes towards medication use 7. Presence of comorbid tics, anxiety 8. Other associated medical problems 9. Associated features similar to medication side effects 10. Combining stimulants with other medications 11. Drug diversion 12. Clinicians’ attitude towards ADHD medications 1. Age dexamfetamine (DEX) is licensed from 3 years of age and methylphenidate (MPH) and atomoxetine (Strattera) from 6 years of age. There is no maximum age to treat ADHD. A caution is needed to use drugs in women of childbearing age as effects of ADHD medications on the foetus and on breast-feeding are unknown. 2. Duration of effect Tasks that require mental effort change over the years. In childhood there may only be a need to treat during daytime while in adolescents, the need to cover the evenings may be necessary. This may be critical for tasks such as driving. 3. The onset of action of the medication When patients require rapid response, stimulants are the treatments of choice. Non stimulant may require two to six weeks to show a treatment response. 4. Comorbid disorders When there is a comorbid disorder along with ADHD, it is generally advised that the ADHD should be treated first. However, major mood disorders like Depression, Bipolar Disorder, and Substance Abuse Disorder should be identified and treated prior to ADHD. If the relevant comorbidity puts the patient at risk for harm to others or to himself/herself, then this comorbidity takes precedence for treatment. It is important to review drug to drug interactions to ensure that there is no risk to the patient. 7 5. History of earlier medication use If there is a lack of improvement or substantial side effects, another ADHD drug may be considered. If a patient is responding well to one medication, it is advised that another medication should not be tried to see if there is a better response. Patients who do not respond to one stimulant may very well respond to another (e.g., MPH vs. DEX). The same seems to be true for side effects; one may be better tolerated than the other. 6. Attitudes towards medication use Patients and their families/carers need to be educated about ADHD and current management. The choice of medication should follow the informed consent. Biases against the use of ADHD medications are often due to misinformation regarding side effects and guilt about having caused the problem due to bad parenting. Alternatively, parents/carers may have excessive expectation from drug therapy and may lead to disappointment. Drugs are part of the holistic approach. 7. Presence of comorbid tics, anxiety Stimulants and non-stimulant may be used in presence of comorbid tics or anxiety. 8. Other associated medical problems It is important for the clinician to do a thorough medical assessment including physical examination before prescribing medications. Many conditions look like ADHD (e.g., hyperthyroidism, hearing deficits, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Learning disability or Specific Learning Difficulty etc). It is important for clinicians to be aware of any other medical condition the patient may have that affects suitability for a medication. 9. Side effects All drugs have side effects. Most side effects usually improve over one to two weeks of continuous use. One of the most common reasons for non-compliance is related to a lack of awareness or understanding of the side effects. Patients’ understanding of the side effect profile of each medication may afford a better compliance. 10. Polypharmacy When a clinician feels that a second medication is needed, it is advised to begin with an ADHD medication that is known to combine safely with the second medication. For example, in the selection of an ADHD medication for a patient with severe conduct disorder and aggressive behaviour, a psychostimulant could be combined with an atypical antipsychotic6. Some of the side effects related to drug interaction occur because of competition for liver enzymes that metabolise the drug. 11. Drug diversion Patients or parents/carers, who are at risk for substance abuse/drugdiversion should not be prescribed short-acting stimulants. 12. Clinicians’ attitude towards ADHD medications Information on ADHD is rapidly evolving (i.e., understanding of comorbidity, adult ADHD, drugs, etc). It is imperative that clinicians have updated information to practice evidence based medicine. 6.4 Follow-up visits Monitor response by using rating scales. Monitor side-effects. Monitor the medication dosage. Parent and teacher rating scales should be obtained for each follow up visit. A telephone call may be beneficial to follow up the prescribed ADHD medication till the dose is optimised. Once a stable optimal dose has been determined, the ideal medication follow-up is 6 months. Non-compliance to treatment may be related to lack of frequency of follow-up. 8 6.5 Monitoring A baseline rating of clinical symptoms is needed before considering medical treatment. The patient may not be the best informant regarding efficacy as they often have poor self-awareness. Helping the adolescent to understand this is a key point in psychoeducation. School performance is a useful indicator of treatment effect. Get information from one teacher the adolescent likes and one they dislike so as to get the best range of teacher observation. Side-effects may be assessed by the parent/carer through the use of a structured questionnaire (appendix I). 6.6 Side-effects If a change of medication is thought necessary because of side-effects, switch medication during school holidays to avoid possible side effects that may impair school performance. If a ‘trial off’ medication is required, it should preferably be done during school holidays to minimize impact on school performance. 6.7 Available drugs in UK ADHD drugs are indicated as part of a comprehensive treatment programme for ADHD. Treatment must be initiated by child and adolescent psychiatrists, paediatricians with expertise in ADHD, ADHD Specialist Nurse Prescribers or GPs with a special interest (GPSi) in ADHD. Methylphenidate and Atomoxetine are not licensed for use in children less than six years of age or in adults. Dexamfetamine may be prescribed after 3 years of age. Stimulants are not licensed for children with marked anxiety, agitation or tension, symptoms or family history of tics or Tourette’s syndrome, hyperthyroidism, angina or cardiac arrhythmia, glaucoma or thyrotoxicosis. Stimulants are controlled by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Schedule 2 drug) and are subject to the regulations for Controlled Drugs. For details the practitioners are advised to consult the European treatment guideline12, 15. 6.7.1 Presentations: Methylphenidate immediate release (IR) is available as 5, 10 and 20mg tablets (5 and 20mg only available as Medikinet and methylphenidate tablets). Medikinet® XL (methylphenidate) is available as 10, 20, 30, and 40mg sustained release capsules. Equasym® XL (methylphenidate) is available as 10, 20 and 30 mg sustained release capsules. Concerta® XL (methylphenidate) is available as 18, 27 and 36 mg sustained release tablets. Dexedrine® (Dexamfetamine) is available as: 5 mg tablets. Atomoxetine (Strattera®) is available as 10, 18, 25, 40, 60 and 80mg capsules. Methylphenidate and dexamfetamine are Schedule 2 Controlled Drugs and therefore prescriptions must be written according to legal requirements. 6.7.2 Recommended dosage and administration Methylphenidate IR Methylphenidate is a central nervous system stimulant. Initial dose can begin at 5mg once or twice daily (2.5mg for a younger child), and increase if necessary by weekly increments of 510mg in the daily dose. If improvement of symptoms is not observed after appropriate dosage adjustment over a one month period, the drug should be discontinued. The maximum recommended dosage for methylphenidate is 0.7mg per dose or 2.1mg daily in divided doses. It is licensed from six years to 17 years of age. Methylphenidate is active for about four hours after the last dose taken. Unwanted effects of appetite suppression can be avoided by advising after 9 breakfast and lunch. Methylphenidate has an effective life of between three and a half and four hours, so the dose regime must be based on this period. Unwanted normal effects of appetite suppression and sleep inhibition are usually accommodated by prescribing to cover the 8am to 6pm period and using it for school days only in most cases. Methylphenidate is active for about four hours after the last dose taken. The inadvertent omission of a dose simply allows the child’s behaviour to revert to the untreated state until the next dose is taken. Methylphenidate sustained release To ensure optimal length of activity to cover the school day, a sustained release preparation may be considered. Table 1 describes the various sustained release preparations available in UK. Long acting stimulants ® Concerta XL Duration of Action Dosage / Day 12 hours Max licensed 54 mg per day 8 hours 10 – 60 mg. 18mg, 27mg or 36mg tablets ® Equasym XL 10mg, 20mg, or 30mg capsules ® Medikinet XL 10mg, 20mg, 30mg & 40mg capsules Max. licensed dose 60 mg per day. 8 hours 10 – 60 mg. Max. licensed dose 60 mg per day. Comments Has 22% IR* & 78% SR# Swallow whole Tablet ‘shell’ may appear in the faeces Has 30% IR* & 70% SR# Swallow whole or empty capsule contents onto one spoonful of apple sauce or similar soft food such as yoghurt Has 50% IR* & 50% SR# Swallow whole or empty capsule contents onto one spoonful of apple sauce or similar soft food such as yoghurt * IR= Immediate release; # SR= Sustained release Equasym XL is a registered trademark of Shire, Concerta XL is a registered trademark of Janssen-Cilag Ltd, Medikinet XL is a registered trademark of Medice GmbH. Dexamfetamine Dexamfetamine is also a central nervous system stimulant. Its effects and adverse event profile are similar to methylphenidate, but there is much less evidence on efficacy and safety that exists for methylphenidate and it plays a part in illegal drug taking. The initial dose may be 2.5mg once or twice daily and increase if necessary by weekly increments of 5-10mg in the daily dose. The maximum licensed dose is 60mg daily in divided dosage. It can be used from 3 years to 17 years of age. The tablets can be halved. Atomoxetine Atomoxetine is a suitable first line alternative and is a non stimulant drug. It may be particularly useful for children who do not respond to stimulants. Certain situations such as co-morbidity with tics, Tourette’s syndrome, epilepsy or substance abuse would support atomoxetine as a first line option. Limited information is available comparing Atomoxetine to stimulants in relation to efficacy. It is available as Strattera® 10, 18, 25, 40 & 80 mg capsules. It is a registered trademark of Eli Lilly. The dose is usually administered as a single daily dose but can also be given twice a day. The starting dose in six years or older and adolescents with body weight up 10 to 70kg is 0.5 mg/kg/day for 7 days. Usual maintenance dose is 1.2 mg/kg/day. In a child and adolescent with body weight at 70kg or more the initial recommended dose is 40mg daily for seven days. The maximum licensed dose is 1.8 mg per kg per day or 120mg per day. The plasma half-life is 3.6 hours in extensive metabolizers and 21 hours in poor metabolizers. Patients on atomoxetine should be monitored for signs of liver functions, depression, suicidal thoughts or behaviour and referred for appropriate treatment if necessary. 6.8 Adverse effects of drugs The most common side-effects reported with methylphenidate treatment are insomnia, decreased appetite, pain in abdomen and headache. They are often mild and transient, and may be alleviated by reducing the dosage. Adjusting dosage times may help to alleviate insomnia. Unwanted effects of appetite suppression can be avoided by advising that the tablets are taken after breakfast and lunch. A very rare but important adverse reaction is bone marrow suppression. A routine full blood count is not warranted unless there is a clinical indication. Abdominal pain and decreased appetite are the most commonly reported adverse effects with Atomoxetine. In the initial period nausea and vomiting can occur in some children. Although rare, suicide-related behaviour (suicide attempts and suicidal ideation) have also been reported in patients treated with Atomoxetine. Hostility (predominantly aggression, oppositional behaviour and anger) is an uncommon adverse effect, occurring in between 0.1 – 1% of patients; treated with atomoxetine. A full list of potential adverse effects is listed in the BNF for children and summary of product characteristics (SPC) of individual drugs. They are also available online on the Electronic Medicines Compendium website (http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/). Side effects which may warrant dose omission until discussed with an ADHD specialist include raised blood pressure, increase in seizure frequency in patients with epilepsy, heart rhythm changes, blurred eyesight, evidence of rare blood disorders. Practice point: Methylphenidate/ dexamfetamine/atomoxetine dependence is not a problem in the drug therapy of ADHD. 6.9 Precautions and Contra-indications A full list of precautions / contra-indications are included in the BNF and Summary of product characteristics. Atomoxetine should be discontinued in patients with jaundice or laboratory evidence of liver injury. Very rarely, liver toxicity with elevated hepatic enzymes and bilirubin has been reported. 6.10 Drug Interactions Methylphenidate increases plasma concentrations of phenytoin and delays intestinal absorption of phenytoin, phenobarbitone and ethosuximide. Methylphenidate inhibits metabolism of tricyclic antidepressants and warfarin. Methylphenidate should be used with caution in patients receiving MAOI’s as there is a risk of hypertensive crisis. Atomoxetine can be combined with stimulants to augment the effect in the case that the clinician feels the patient has not achieved an adequate response4. Such a combination should be initiated by a secondary care provider with specialization in ADHD. The combinations are used sometimes in clinical practice although it is not recommended nationally. Results from the handful of studies suggest that combining stimulant therapy with nonstimulant alternatives may result in more significant symptom reductions in patients for whom monotherapy is less than optimal. There are no studies to suggest that combing stimulant with a non-stimulant increases the risk of cardiac side-effects. The best practice will be to exclude any family history and a cardiac evaluation before start of a drug trial. 11 Full lists of drug interactions are included in the SPC. 6.11 Drug holiday Recent evidence suggests that minor height changes (up to 2 cm) may occur on stimulants 9 although it is unclear whether ADHD children tend to be smaller. If there is concern then families should be given the option of whether to have drug holidays or to lower the dosage on weekends and during school holidays. Non-stimulant medications must be given continuously as they rely on a blood level being sustained for treatment efficacy. Maintaining some medications continuously has the additional advantages of allowing side effects to settle and enabling the child to behave more consistently, thereby improving their self-esteem and social skill abilities. 7 OTHER MANAGEMENT OPTIONS 7.1 Behavioural interventions ADHD patients may take longer time to integrate socially acceptable habits into their lives. The key factor is to create a positive environment that motivates the individual. 7.2 Psychological treatment ADHD patients are at significant risk of being involved with bullying as a bully, as a victim or both. There is a direct effect on their self-esteem. They require a positive environment and sensitivity and understanding. Interventions may include individual and/or family support, counseling, and therapy. 7.3 Educational modifications A child with ADHD should have access to additional educational needs where necessary. 8. ADOLESCENTS Adolescents may present differently than younger children. They are less likely to be as overactive, although they may be fidgety and can be restless. Low self-esteem may result from school underachievement. 8.1 Medical Evaluation In addition to the history and physical examination mentioned in 5.2, medical evaluation of the adolescent should include eliciting history regarding: Eating habits Menstrual/pubertal status. Use of alcohol and drugs. Cigarette smoking. Driving. 8.2 8.3 Psychosocial Evaluation Specific precipitant where symptoms can be dated. Events precipitating ADHD symptoms such as neglect, physical or sexual abuse. Parenting issues and Home environment. School Evaluation Completed rating scales from school. Adolescents often can give guidance about which teachers know them best. School report. Psychometric evaluation by education psychologists for cognitive abilities, academic achievement levels, and learning disabilities. 12 8.4 8.5 Social History History of substance use. Number of accidents and speeding tickets. Sexual activity and use of contraceptive methods. Spending history (gambling, shopping). Compliance Between a third and a half of medicines that are prescribed for long-term conditions are not used as recommended7. As many as 48-68% of adolescents stop their ADHD medications. 8 Psychoeducation is the most useful means of ensuring compliance. The primary aim should be to get the adolescent to take responsibility for his/her own medications. Parents/guardians involvement may be necessary to ensure that medication is taken as scheduled. However, a power battle will inevitably result in poor compliance and it may be more important to just involve the adolescent alone. Once-daily dosing improves compliance. 8.6 Safety Issues It is good practice to explain to a teenager about the condition and the option of various drugs to gain her/his confidence. Combining medications for ADHD with illicit drugs or alcohol could be dangerous as the effects may be exaggerated. The use of medications may protect them from poor social skills so it is helpful if they do not skip the dosage on weekends and during school holidays. 8.7 Pharmacokinetics Puberty is a time of significant physical change and the adolescent patient may be develop side effects in small doses. It is recommended that the first dose should be low but with gradual increase. The concurrent use of illicit substances is likely to increase the blood levels of most drugs metabolised in liver. There is no established dose-response curve for adolescents. 9. Guidelines There are many guidelines including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Guidelines10, the American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines11, the European Treatment Guidelines12, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence13 and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network14. 10. COMORBIDITIES 10.1 Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) In childhood, the most common comorbid disorders are ODD in as many as 40% of ADHD children15. ODD is characterized by the child’s inability to accept parental authority and the strong need to be in control. Distinguishing between normal adolescent self-assertion and ODD may not always be easy. Treatment of the ADHD may not resolve all ODD symptomatology, which may require additional individual and family interventions. Behavioural interventions are important. Strategies leading to positive reinforcement and targeting positive goals are often useful. Use of time-out and appropriate strategies that are applied with consistency also help to deal with the oppositional defiance. Behavioural interventions are effective, but they need to be consistent and ongoing. 10.2 Conduct Disorder (CD) The risk for the development of CD in children with both ADHD and ODD is two to three times greater than in children with ADHD without ODD16. Behavioural intervention strategies are 13 necessary for this disorder. Comorbid CD also puts children at risk for gravitating towards other children with similar problems. Strategies that promote positive peer relationships and effective empathy development are indicated. A medication trial may be advised in conjunction with comprehensive psychosocial treatment. 10.3 Learning Disability (LD) Children with ADHD frequently fall below control groups on standardised achievement tests. Children with ADHD often have weaknesses in the cognitive areas of executive functioning, working memory and processing speed. When psychoeducational assessments are done, emphasis should be placed on assessing these weaknesses as well as written output and auditory processing. If LDs are documented, it may attract more one to one support and ageappropriate educational progress. 10.4 Aggression Verbal and physical aggression is not uncommon in ADHD. The most common reason why children with ADHD would act aggressively is a combination of ADHD with either ODD or CD. Treating the ADHD is usually the first step. However, aggression might be part of another diagnosis. Behavioural interventions and all ADHD medications may decrease aggressive behaviour. If needed, new generation antipsychotic medications can be tried. A study has shown that risperidone is effective in controlling ADHD, ODD and CD17. 10.5 Bipolar Disorder (BD) This is an uncommon disorder in childhood. BD should be considered as the primary diagnosis if there are prominent, episodic, cycling mood symptoms. BD may be suggested by: a) a strong family history of BD or depression, b) paradoxical response to stimulants (worsening of mood or rage symptoms).If BD is suspected, referral to a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist is recommended. 10.6 Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD) PDD presents with difficulties in social communication, social interaction and stereotyped, repetitive behaviour. Clinical symptoms of PDD supersede that of ADHD and should be the primary diagnosis and can co-exist. The FDA recently approved the use of risperidone in controlling aggressive and self-injurious behaviour and irritability18. 10.7 Depression Many patients with Major Depression may present with transitional inattention, short-term memory problems, irritability and impulsivity related to the mood disorders. When the depression is associated with problems in the social environment, treatment strategies including individual and family therapy are primarily indicated. Poor concentration may be part of a clinical depression. A diagnosis of depression involves both a) depressed mood of more than two weeks in duration more days than not and b) anhedonia. The stimulant medications may produce a dysphoric look in 30% of patients even though the patient is not clinically depressed. Adjustment of dose or switching to a different ADHD drug may improve the dysphoric symptoms. Treatment of the most disabling condition should be undertaken first. This is particularly true in the presence of suicide risk. Stimulants may produce a mild antidepressant effect in some patients, while they may worsen mood in others. All of the drugs used to treat ADHD have the potential to unmask a mood disorder or to cause mood symptoms. 10.8 Anxiety Anxiety in ADHD can be manifested as Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Phobia, Separation Anxiety Disorder, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD). PTSD may be a misdiagnosed as ADHD as there are similar symptom complex. PTSD is likely if there is no clear family history of ADHD or pre-morbid symptoms of ADHD prior to the traumatic situation. If OCD exists then the combination with ADHD may be 14 part of a Tic Disorder (e.g., Tourette’s syndrome) so it is important to look for motor and phonic tics. 10.9 Tic Disorders Atomoxetine is a non-stimulant medication which does not aggravate tics. Stimulant medications can be used to treat ADHD with tic disorders, but caution should be exercised as tics may be exacerbated in some children. 10.10 Epilepsy Children/adolescents with ADHD and comorbid epilepsy are at increased risk of seizures. There is no available evidence that ADHD drugs decrease the seizure threshold. Therefore GSF is of the opinion that ADHD drug may be used in such a situation. 10.11 Substance Use/Abuse Disorder (SUD) ADHD patients are at increased risk of using illicit substances. It is important to point out that the use of illicit substances does not have a positive therapeutic benefit. It is essential that a history for substance abuse is explored with the individual alone. Ask whether their friends use drugs or alcohol. A positive response suggests they are likely to be at high risk for substance use. 11. CARDIAC RISKS OF ADHD MEDICATIONS: Sudden death in the ADHD population occurs in similar proportion to the general population. Associated conditions in patients with sudden death on ADHD medications are very similar to those with sudden death in the general population (structural heart disease, history of syncope, family history of sudden death, exercise induced sudden death), and some of these clues can help to suspect a higher risk, whether in the untreated or treated population. ECG abnormalities can identify some individuals in the general population at risk for sudden death. Cost-Benefit ratio in the school-age children is not clear and the usefulness of ECG screening in patients being treated with or considered for ADHD drugs is unknown. The small but unproven potential contribution of ADHD drugs to the rare incidence of sudden death in children and adolescents must be weighed against the clinical benefit of the medication. Risk/benefit should be discussed with the parent/patient as appropriate. In patients with cardiac conditions that place them at increased risk for sudden death, ADHD medications should be contemplated only after paediatric cardiology consultation and a thorough discussion of the risks and potential benefits with the patient, family and consultants. In a child or adolescent with ADHD, who has no cardiac symptoms, the risk of cardiac adverse events from ADHD medications is very low. The American Heart Association Recommends19: 1. Before therapy with psychotherapeutic agents is initiated, a careful history should be obtained with special attention to fainting or dizziness particularly with exercise, complaint of chest pain or shortness of breath with exercise and about seizures. Medication use (prescribed and over-the-counter) should be determined. The family history should focus on the long QT syndrome, sudden cardiac death or heart attack in members below 35 years of age and history of Marfan syndrome. Presence of these symptoms or risk factors warrants a cardiovascular evaluation by a paediatric cardiologist before initiation of therapy. 2. At follow-up visits, patients receiving psychotropic drug therapy should be questioned about the addition of any drugs and the occurrence of any of the cardiac symptoms. The physical examination should include checking heart rate and blood pressure. 15 12. INTERVENTIONS 12.1 Objectives The followings should be the objectives of any intervention: To inform child/adolescent and families/carers about the aetiology, diagnosis, and various management options of ADHD. To obtain the view of the child/adolescent and families/carers in making the choice of intervention. To guide parents/carers to appropriate support groups. 12.2 Information about ADHD Parents/carers should be informed that ADHD is a neuro-behavioural condition with a strong genetic aetiology. It involves neurotransmitters and affects certain areas of the brain. Parents/carers also need to be informed about the reason for comprehensive evaluations including medical, psychiatric, and cognitive areas, in order for the diagnosis to be made. They should be explained about the need to rule out other possible diagnoses. Subsequently various treatment options need to be explored with them. 12.3 Therapeutic Options The child’s surroundings should be supporting routines and decrease distractions. Consistent age-appropriate limit setting is important. Retaining a positive, enjoyable relationship with their child improves his/her self-esteem. Thus, doing things that the child excels at or enjoys is very important. Parents will need to advocate for the child with schools for appropriate support and assistance and keep in close and frequent communication with teachers regarding academic expectations and progress or deficits, as well as social and classroom behaviour. Parents/carers also need to help the child to develop appropriate social behaviours with peers and adults outside of school. Parents may have difficulty carrying out the activities outlined above because they themselves have ADHD and/or another condition (e.g., depression, anxiety, substance abuse). Other conditions such as medical problems, unemployment, poverty, single parenthood or marital discord need to be taken into account in working with parents. It is important to think about possible parental pathology and identify it in order to refer the parent for appropriate treatment, as without such treatment parents frequently cannot help their child. Whenever possible, an attempt should be made to work with both parents so that the child receives the benefit of having the help of each of them, and parents are consistent with each other in their approaches. Furthermore, sharing this responsibility helps to ensure that one parent does not become overwhelmed. 13. TREATMENT OPTIONS 13.1 Psychosocial Therapies Parents/carers should be informed that children with ADHD may have additional social, academic, and emotional problems. They may therefore require a variety of psychosocial/educational interventions, depending upon the need. Interventions such as the following may be needed for the child and family: Additional help with academic progress. social skills training. individual psychotherapy. parent training. family therapy. lifestyle changes to improve sleep. 13.2 Medication Parents/carers should be explained in simple language about the advantages and disadvantages of various available drugs, including short and long-acting stimulants, and non16 stimulant. Concerns and questions parents may have regarding both effects and side effects need to be addressed with a clear description about common side effects and how these can be monitored and dealt with? An exploration of what medication can and cannot be expected to do, and what other interventions should be explained. 13.3 Parents and home situation While interviewing parents, one needs to obtain a comprehensive knowledge of each parent’s medical and psychiatric history and past and current level of functioning in various situations such as occupational, academic, social, and emotional. Particular family situations, such as a single working parent, separated or divorced parents, or reconstituted families where one or both parents have remarried, all affect the child with ADHD and the parents’ ability to help their child. Exploring the family situation is thus crucial to identify problems and address them if they exist. Relationships between the parents, the parent and child, siblings, and other significant extended family members (e.g., grandparents, uncles/aunts, stepparents, and stepsiblings), need to be explored in order to identify strengths and weaknesses in these relationships. 13.4 Parental Psychopathology It is well known that ADHD runs in families. Parents, siblings, and extended family members may be affected and therefore have problems with organisation, consistency, impulsivity, and emotional liability. Substance abuse may also be more common in adults with ADHD. In addition, having a child with a disability may increase the likelihood of depression and anxiety in the parents. Parental psychopathology can have a significant impact on the parents’ ability to structure, monitor, and help their child. Identifying this psychopathology and referring the parents for appropriate advice and guidance may improve the psychiatric state of the parents and their parenting ability, and thus be of great help to the child and his/her family. 13.5 PRACTICE POINT: Make sure to review the child’s strengths, not just his/her areas of weaknesses. This establishes a rapport with the child and family that makes future visits easier and can aid intervention planning. If there are any signs or symptoms of a physical illness that may be a factor in explaining the clinical symptoms, this takes precedence in the evaluation. Begin the interview by talking about the child’s strengths. The child may not show clinical symptoms in the clinic. If there are obvious symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention, it suggests that the symptoms are more severe. Assess whether there are any life events that are of emotional concern (e.g., abuse, deaths, changes in family dynamics etc). Ask the child to draw a picture of themselves and then their family on the same page. This helps to determine the child’s perspective of the family. Note any unusual perceptual differences like drawing themselves bigger than the parents. Liaise with GP if one or both of the parents needs an assessment for ADHD or other psychiatric disturbance if it appears evident. 14. MANAGEMENT OF SOME COMMON PROBLEMS 14.1 Sleep difficulties Problems with sleep are a common complaint among ADHD patients of all ages. Any decrease in sleep quality and / or quantity may lead to worsening of behaviour, mood, alertness and level of concentration. It is therefore important to screen for sleep difficulties. The acronym BEARS is useful for this purpose: Bedtime resistance and delayed sleep onset Excessive day time sleepiness Awakenings during night Regularity, pattern and duration of sleep Snoring and other symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing20. 17 The causes of ADHD related sleep problems may include the following: Anxiety Oppositional Defiant Disorder Primary sleep disorders o Obstructive Sleep Apnoea o Restless Leg Syndrome o Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome Stimulant medications may increase the difficulty of falling asleep Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome is a sleep disorder which occurs approximately in 7% of teenagers. Here the teenager falls asleep later than the expected time, has a normal sleep at night but wakes up late the next day. Stimulant Induced Insomnia: Administer medication as early as possible in the morning. Similarly, giving the medication early in the morning and letting him/her go back to sleep allows the medication to wake him/her up. Try to assure that the patient is not in rebound at the time that they are trying to fall back asleep, by either lowering he dose late in the day or shaping a slow offset of action. 14.2 Sleep Hygiene Optimize sleep hygiene by: Maintaining a quiet and comfortable sleep environment. Maintaining a consistent time of going to bed and waking in the morning. Exposure to activities such as watching television, playing computer games or going on chat lines will disrupt the initiation of sleep, despite beliefs that these activities promote fatigue. It is helpful if the individual is physically active through the day (though not within two hours of bedtime) to aid in physical exhaustion. Limit the use of the bed to sleep only as this will create a positive association. The bed is not for watching TV, eating, or doing homework. Avoid food or drinks containing caffeine such as chocolate, coffee, tea and cola in the late afternoon and evening. 14.3 Role of melatonin Melatonin is a natural hormone produced by the pineal the gland in the brain. It is a sleep inducer and helps to fall asleep at night. Certain foods are rich in melatonin such as oats, rice, sweet corn, barley and tomatoes. Foods that are high in tryptophan, a common amino acid found in many foods including turkey, beans, rice, hummus, lentils, hazelnuts, peanuts, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, tuna, soy milk, cow's milk, and other dairy products. Melatonin 2-10 mg may be administered 30-60 minutes before the bedtime for children with significant difficulty getting to sleep. We have no available information on the safety and efficacy of melatonin use on long-term. 14.4 Appetite Many parents complain that their children are 'picky eaters'. In addition, stimulant medication further suppresses appetite and often shifts the timing of food intake to periods of the day in which stimulant blood levels are waning. Early studies of the relationship between special diets, sugar, food dye, food allergies and ADHD did not confirm that diet is a significant contributor to the aetiology of ADHD. Children who receive continuous stimulant medication are found to show growth deceleration as compared to children who do not receive medication for up to three years, but it is not evident that they end up shorter than control children upon reaching maturity. Parents who are concerned about their child not eating, eating too much junk food, or refusing to eat a particular food group are reassured if the time is taken to review dietary intake and given strategies to encourage good nutrition. In particular children with ADHD may not sit for 18 long meals, may need to snack when medication wears off, and benefit from access to healthy snacks. 14.5 Strategies to Improve Appetite Reassure parents that although the child may lose weight, this will stabilize, but the child's height percentiles will not change. This information helps to reduce parents' anxiety. Dry mouth can be a side effect of medication, the patient may have significant thirst. Allowing them to have frequent fluids throughout the day and high protein/high calorie drinks for lunch is usually sufficient to maintain their caloric needs. In the evenings when there may be rebound appetite, supper can be spread out into two or three sessions. Let the child eat whatever they want for breakfast (e.g. even a peanut butter and jelly sandwich). Engage the child in meal preparation and in shopping for their favourite foods. Switch to whole milk. Prepare nutritious snack foods. 15. CARE PATHWAY Appendix 2 is an example of the Care pathway that can be implemented after local modifications. 16. SHARED CARE Appendix 3 is an example of the Shared Care template that can be used in the local Trusts with appropriate changes, if needed. 19 REFERENCES 1. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. Clinical Guideline 72.www.nice.org.uk 2008. 2. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 2006;36:15965. 3. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association 2000. 4. World Health Organization: The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines, World Health Organization 1992. 5. Canadian ADHD Practice Guideline 2008. http://www.caddra.ca/cms4/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=26&Itemid= 70&lang=en (accessed on 19 April 2010). 6. Turgay, A. Treatment of comorbidity in conduct disorder with Attention-Deficit /Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Special Report). Essential Psychopharmacology, 2005. 6(5): 277-290. 7. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Medicines adherence: Involving patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. Clinical guideline 76, 2009. www.nice.org.uk/CG76 9accessed on 18 April 2010). 8. Charach, A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R. Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2004. 43(5): 559- 67. 9. Swanson JM, Elliott GR, Greenhill LL, et al. Effects of Stimulant Medication on Growth Rates Across 3 Years in the MTA Follow-up. Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007, 46(8):1015-1027. 10. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007. 11. American Academy of Pediatrics, Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the schoolaged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 2001. 108: 1033-1044. 12. Banaschewski, T, Coghill D, Santosh P, et al. Long-acting medications for the hyperkinetic disorders: A systematic review and European treatment guideline. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2006. 15(8): 476-95. 13. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. Clinical guideline 72. www.nice.org.uk 2008 14. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Attention Deficit and Hyperkinetic Disorders in Children and Young People. A national clinical guideline 52. www.sign.ac.uk 2001 15. Taylor E, Dopfner M, Sergeant J, et al. European clinical guidelines for hyperkinetic disorder – first update. Eur Adolesc Psychiatry [Suppl 1]. 2004. 13: 1/7- 1/30. 16. Barkley, R.A., Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Handbook. Third Edition. 2005, New York: Guildford Press. 17. Aman, M.G, Binder C, Turgay A. Risperidone effects in the presence/absence of psychostimulant medication in children with ADHD, other disruptive behavior disorders, and subaverage IQ. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol, 2004. 14(2): 243-54. 18. Shea, S, Turgay A, Carroll A, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics, 2004. 114(5): e634-41. 19. Vetter VL, Elia J, Erickson C, et al. Cardiovascular Monitoring of Children and Adolescents With Heart Disease Receiving Stimulant Drugs: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young 20 20. Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee and the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Circulation, 2008. 117: 2407- 23. Owens, JA and Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med, 2005. 6(1): 63-9. 21 Appendix 1. Side-effects Questionnaire (parents/carers) Child’s Name: ____________________________________D O B Date_____________________ All medication has side-effects; some are more troublesome than others. We want to make sure that children who are taking medication do not suffer, even if their work and behaviour benefit from it. For each item, please tick in a box on each line how much that word or statement applies to your child over the last few days according to your own observations 0 1 2 3 4 is not at all is a few occasions only is about half the time is most of the time is all the time (not observed) 0 1 2 3 4 (all the time) Talks less than usual with other children Poor appetite Irritable Complains of stomach ache Complains of headache Drowsy Looks sad, miserable Looks anxious Seems unsteady Excited Angry Has nightmares Displays twitches (tics) Is there anything else you would like to add? _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ Thank you very much 22 Appendix 2. Care pathway Problems with attention, impulsivity, hyperactivity. GP, Health visitor, Special Educational Needs Coordinator, Class Teacher, school nurse Consider CAF Referral to ADHD clinic Mental health issues identified ADHD confirmed Lead professional CAMHS referral Refer appropriately On-going monitoring in ADHD clinic 23 Appendix 3 Shared Care Agreement This shared care agreement describes the responsibilities for both specialist and general practitioner (GP) in sharing the care and managing the prescribing of ADHD drugs. Shared care assumes to share the management of the patient including the prescribing of ADHD drug. This process should begin with a discussion of the process with the patient, providing an opportunity for the specialist to discuss drug therapy with the patient and carer. During shared care the specialist will provide regular follow-up and appropriate communication. RESPONSIBILITIES and ROLES Secondary Care Assessment and diagnosis. If diagnosis of ADHD confirmed, measure BP, Height & weight. If medication is considered, initiate and titrate to the effective dose, continue treatment for at least three months. Provide information and management options to parents. Monitor ADHD symptoms with parents and if possible with teachers. Offer other treatment options if needed. If patient is stable refer to the GP for shared care. Monitor patient yearly and communicate results of review to GP. Stop medication if ineffective or produces undesirable side effects Primary Care Provide repeat prescriptions. Monitor pulse and blood pressure every three months. Monitor height and weight every six months. Contact the specialist if concerned about any aspects of patient’s treatment. Refer back to secondary care for: Psychological interventions. No gain in weight or loss in weight. Unmanageable side effects of medication. Mental instability. Raised pulse, BP and/or cardiac symptoms. 24 Members of the GSF producing these guidelines Dr Chinnaiah Yemula Dr Neel Kamal Dr Somnath Banerjee With the input from other executive committee members. 25 GSF Executive committee 2010/2011 Advisers: Prof Nick Spencer Dr Val Harpin Chairman: Dr Geoff Kewley Convenor: Dr Somnath Banerjee Treasurer: Dr Jayantha Perera Members: South England: Deputy: Dr Elaine Clark Dr K Puvanandran North England: Deputy: Dr Hani Ayyash Dr Neel Kamal Scotland: Deputy: Dr Diana Leaver Dr Kate Reid Wales: Deputy: Dr Stephen Mackereth Vacant Northern Ireland: Deputy: Dr Larry Martel Dr Eleanor Brown Subcommittees: Academic: Chair Members Newsletter: Chair Members 1. 2. 3. Dr Hani Ayyash Dr N Kamal Dr Cyril De Silva Dr Diana Leaver 1. 2. 3. Dr S J Perera Dr Suresh Nelapatla Dr Trish Fowlie Dr Naeem Ashraf Youth Justice: Chair Members 1. 2. 3. Dr Geoff Kewley Mrs. Margaret Alsop (associate) Dr Rashmin Tamhne Dr Inyang Takon 26 NICE Guidelines Implementation Group: Chair Members 1. 2. 3. Dr Marietta Higgs Dr Ian Male Dr C Yemula Dr Lakshman Doddamani Trainee rep: Dr Hamilton Grantham 27