Prepared for the Maritime Policy Task Force of the European

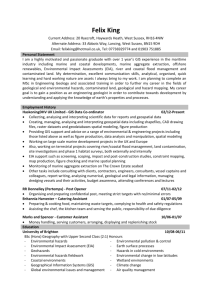

advertisement