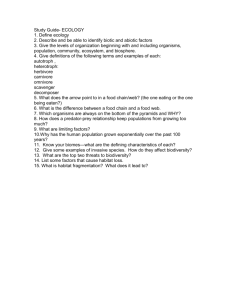

Biodiversity Assessment in preparation for

advertisement