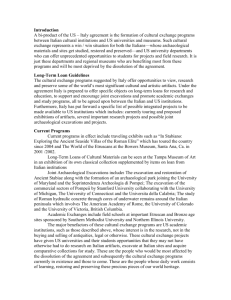

Deborah A. Bekken - Saving Antiquities for Everyone

advertisement

March 15, 2005 Mr. Jay Kislak Chair, Cultural Property Advisory Committee U.S. Department of State 301 4th Street, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20547 Re: Comments submitted at CPAC public meeting 17 February 2005 Dear Mr. Kislak: I have worked on archaeological projects in China for 15 years and at sites located in at least six provinces. This has included field excavations as well as collections-based work at previously excavated sites. I work primarily with very old sites dating to either the Neolithic or Paleolithic. My field of specialization, faunal analysis or zooarchaeology, focuses on the excavation, analysis, and interpretation of the animal bones that are so commonly found in archaeological contexts. These artifacts are not beautiful or desirable to the collector, but they are incredibly valuable in helping us to understand the full meaning of the sites that we excavate. Understanding where each artifact lies in context with every other artifact is essential to the practice of archaeology. Artifact hunting and looting destroys the context of a site and essentially ruins our one best chance to collect all the data that would help us to understand the meaning of a site. This is, I believe, the central most important reason why import restrictions on archaeological materials are worthy of support. It is impossible to overstress the value of intact archaeological context to the excavator. With good control over space and depth we have a window into how people organized themselves at the individual, group, and society level. Without good control over the provenience of artifacts, we are left to guess at their age, their function, and their relevance to the society that made them. For example, the ancient practice of burying the dead with grave goods provides a wealth of information, but it also renders burials one of the most vulnerable components of a site. Grave goods can tell us about people’s lives, about the organization of society, and about the nature of social relationships if we can compare across many examples. We do this by looking at the quality, quantity, and placement of objects within a tomb. Burials also teach us about religious beliefs and ritual practice through the nature of the interments and the use and placement of specialized artifacts such as the carved jade Bi disks that are usually placed over the chest. If we make comparisons across sites or across time we can begin to see patterns that can be indicative of, for example, the accumulation or loss of economic and social power relationships on a regional scale. China has been roundly criticized in the media for failing to protect its heritage and for rampant corruption that feeds a growing local and international market. My own experience, however, has been quite different. In virtually every province in which I have worked, the personnel of the local Cultural Relics Management Bureaus have been committed professionals that take great care to provide protection for excavated collections materials. In many cases they are short on resources, but they manage to find collections facilities and caretakers in any case. These range from well-curated collections in university and research institutes to simpler storage and access control solutions in small site museums and field stations. For example, at a Longshan site in Shandong province where Anne Underhill and I are currently working, the high value pottery, a distinctive form of eggshell thin black reduction ware, is housed on the top floor of the local museum. In order to get into that storeroom, you need to pass through four locked doors, requiring four separate keys, and each key is in the possession of a different individual. Two of the doors are barred metal gates that are set directly in the concrete of the building. If a person wanted to get into that storeroom to take some of the pottery, he would have to bribe not one individual, but at least four people in order to gain access. In addition, China does devote resources to rescue excavations where possible. The Three Gorges Dam project will inundate sites throughout the affected stretch of the Yanzi River behind the dam. Regardless of one’s opinion of the Three Gorges Dam project, it would be inaccurate to say that China is not taking any steps to try to mitigate the impact on local archaeological sites. I know I have had the experience over the last few years, and I am sure that several of my colleagues have as well, of learning through emails that one or another Chinese colleague is off to the Three Gorges on a rescue excavation project. These efforts will very likely not be enough to satisfy the international community, but nevertheless they are not insignificant. There is currently more collaborative research and cultural exchange between China and the US than ever before. Loans of artifacts for exhibition and research as well as intellectual connections between scholars, students, and the public have increased dramatically since the late 1980s. In my own work, loans of artifacts for research purposes were not permitted when I first started working in China but are now relatively easy to arrange. A greater sense of safety regarding archaeological resources should increase, rather than decrease, cultural exchanges with China. People in China everywhere I have worked are knowledgeable and sophisticated with regard to their own history and prehistory. There is tremendous interest in these subjects, and any archaeologist working in the area can relate numerous requests to talk with television reporters, local officials, and local schools about ongoing excavations and about the lives of people and societies in the past. While everyone can appreciate the beauty, artistry, and creativity of early artifacts, a more patient and controlled approach to their excavation can yield an abundance of additional information that is invaluable to our understanding of our collective experience. Anything that we can do to lessen the demand for illegally excavated artifacts may help to reduce their supply as well. Sincerely, Deborah A. Bekken Adjunct Curator, Anthropology