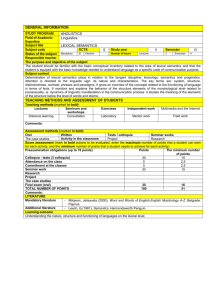

UNIVERSITATEA DIN CRAIOVA

advertisement

UNIVERSITATEA DIN CRAIOVA

FACULTATEA DE LITERE

ÎNVĂŢĂMÂNT LA DISTANŢĂ

PROGRAMA ANALITICĂ

Disciplina: Curs opţional: Basic Elements of English Semantics

Specializarea: Română- Engleză

Anul III, Semestrul I +II

Titularul disciplinei: lector Claudia Pisoschi

I. OBIECTIVELE DISCIPLINEI:

Cursul îşi propune:

definirea domeniului semanticii, a locului şi rolului acesteia în cadrul

lingvisticii; evidenţierea relaţiilor cu celelalte discipline lingvistice: lexicologia,

morfo-sintaxa, pragmatica;

prezentarea unui scurt istoric al semanticii, vazuta in contextul celorlalte

discipline lingvistice;

predarea noţiunillor de bază din domeniul semanticii , cu accent pe teoriile

legate de sens;

descrierea principalelor tipuri de motivare a sensului;

prezentarea abordarilor structurale in analiza sensului, cu accent pe rolul

analizei componentiale;

în cadrul fiecarei teme studiate se pune accent atât pe aspectele teoretice cât şi

pe cele practice, fiecare capitol cuprinzând şi câteva exerciţii pentru aplicarea

cunoştinţelor teoretice acumulate.

II. TEMATICA CURSULUI:

Capitolul I. Introduction to Semantics

1. A Short History of Semantics

2. Definition and Object of Semantics

3. Semantics and Semiotics

Capitolul II. The Problem of Meaning

I. The Concept of Meaning: 1.a bipolar relation

2.a triadic relation:

a. referential approach

b. conceptual approach

3. Heger’s view

II. Dimensions of Meaning 1. dimensions of meaning

2.types of meaning in Leech’s conception

Capitolul III. Motivation of meaning.

1. Absolute motivation

2. Relative motivation

Capitolul IV. Structural Approaches to the Study of Meaning

1. Componential Analysis

2. Paradigms in Lexic. The Semantic Field Theory

III. EVALUAREA STUDENŢILOR:

Forma de evaluare: examen scris

IV. BIBLIOGRAFIE GENERALĂ:

1. Chiţoran, Dumitru.1973. Elements of English Structural Semantics, Bucureşti:

Editura Didactică şi Pedagogică

2. Ionescu, Emil. 1992. Manual de lingvistică generală ,Bucureşti: Editura All

3. Leech,G. 1990 Semantics .The Study Of Meaning. London: Penguin Books

4. Lyons, J. 1977.Semantics vol I, II, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

5. Saeed, J.I. 1997. Semantics,Dublin: Blackwell Publishers.

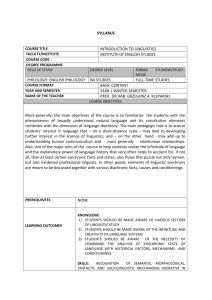

PREZENTAREA CURSULUI

Capitolul I. Introduction to Semantics.

4. A Short History of Semantics

5. Definition and Object of Semantics

6. Semantics and Semiotics

Capitolul II. The Problem of Meaning .

I.The Concept of Meaning: 1.a bipolar relation

2.a triadic relation:

c. referential approach

d. conceptual approach

3. Heger’s view

III. Dimensions of Meaning 1. dimensions of meaning

2.types of meaning in Leech’s conception

Capitolul III. Motivation of meaning.

3. Absolute motivation

4. Relative motivation

Capitolul IV. Structural Approaches to the Study of Meaning

1. Componential Analysis

2. Paradigms in Lexic. The Semantic Field Theory

Chapter I

INTRODUCTION TO SEMANTICS

Why study semantics? Semantics (as the study of meaning) is central to the

study of communication and as communication becomes more and more a crucial

factor in social organization, the need to understand it becomes more and more

pressing. Semantics is also at the centre of the study of the human mind - thought

processes, cognition, conceptualization - all these are intricately bound up with the

way in which we classify and convey our experience of the world through language.

Because it is, in these two ways, a focal point in man's study of man, semantics

has been the meeting place of various cross-currents of thinking and various

disciplines of study. Philosophy, psychology, and linguistics all claim a deep interest

in the subject. Semantics has often seemed baffling because there are many different

approaches to it, and the ways in which they are related to one another are rarely clear,

even to writers on the subject. (Leech 1990: IX).

Semantics is a branch of linguistics, which is the study of language; it is an

area of study interacting with those of syntax and phonology. A person's linguistic

abilities are based on knowledge that they have. One of the insights of modern

linguistics is that speakers of a language have different types of linguistic knowledge,

including how to pronounce words, how to construct sentences, and about the

meaning of individual words and sentences. To reflect this, linguistic description has

different levels of analysis. So - phonology is the study of what sounds combine to

form words; syntax is the study of how words can be combined into sentences; and

semantics is the study of the meanings of words and sentences.

1.

A Short History of Semantics

It has often been pointed out, and for obvious reasons, that semantics is the

youngest branch of linguistics (Ullmann 1962, Greimas 1962). Yet, interest in what

we call today "problems of semantics" was quite alive already in ancient times. In

ancient Greece, philosophers spent much time debating the problem of the way in

which words acquired their meaning. The question why is a thing called by a given

name, was answered in two different ways.

Some of them believed that the names of things were arrived at naturally,

physei, that they were somehow conditioned by the natural properties of things

themselves. They took great pains to explain for instance that a letter like "rho" seems

apt to express motion since the tongue moves rapidly in its production. Hence its

occurence in such words as rhoein ("to flow"), while other sounds such as /s, f, ks/,

which require greater breath effort in production, are apt for such names as psychron

("shivering") or kseon ("shaking"), etc. The obvious inadvertencies of such

correlations did not discourage philosophers from believing that it is the physical

nature of the sounds of a name that can tell us something about its meaning.

Other philosophers held the opposite view, namely that names are given to

things arbitrarily through convention, thesei. The physei-thesei controversy or physisnomos controversy is amply discussed in Plato's dialogue Cratylus. In the dialogue,

Cratylus appears to be a part of the physei theory of name acquistion, while

Hermogenes defends the opposite, nomos or their point of view. The two positions are

then debated by Socrates in his usual manner. In an attempt to mediate between the

two discussants he points out first of all that there are two types of names. Some are

compound names which are divisible into smaller constituent element and

accordingly, analyzable into the meaning of these constituent elements: Poseidon

derives his name from posi ("for the feet") and desmos ("fetter") since it was believed

that it was difficult for the sea god to walk in the water.

The words, in themselves, Socrates points out, give us no clue as to their

"natural" meaning, except for the nature of their sounds. Certain qualities are

attributed to certain types of sounds and then the meaning of words is analyzed in

terms of the qualities of the sounds they are made of. When faced with abundant

examples which run counter the apriori hypothesis: finding a "l" sound ("lambda")

"characteristic of liquid movements" in the word sklerotes ("hardness") for instance,

he concludes, in true socratic fashion, that "we must admit that both convention and

usage contribute to the manifestation of what we have in mind when we speak".

In two other dialogues, Theatetus and Sophists, Plato dealt with other

problems such as the relation between thought language, and the outside world. In

fact, Plato opened the way for the analysis of the sentence in terms which are parly

linguistic and partly pertaining to logic. He was dealing therefore with matters

pertaining to syntactic semantics, the meaning of utterrances, rather than the meaning

of individual words.

Aristotle's works (Organon as well as Rhetoric and Poetics) represent the next

major contribution of antiquity to language study in general and semantics in

particular. His general approach to language was that of a logician, in the sense that he

was interested in what there is to know how men know it, and how they express it in

langugage (Dinneen, 1967: 70) and it is through this perspective that his contribution

to linguistics should be assessed.

In the field of semantics proper, he identified a level of language analysis - the

lexical one - the main purpose of which was to study the meaning of words either in

isolation or in syntactic constructions. He deepened the discussion of the polysemy,

antonymy, synonymy and homony and developed a full-fledged theory of metaphor.

The contribution of stoic philosophy to semantics is related to their discussion

of the nature of linguistic sign. In fact, as it was pointed out (Jakobson, 1965: 21, Stati

1971: 182, etc.) centuries ahead of Ferdinand de Saussure, the theory of the Janus-like

nature of the linguistic sign - semeion - is an entity resulting from the relationship

obtaining between the signifier - semainon - (i.e. the sound or graphic aspect of the

word), the signified - semainomenon (i.e. the notion) and the object thus named tynkhanon -, a very clear distinction, therefore, between reference and meaning as

postulated much later by Ogden and Richards in the famous "triangle" that goes by

their name.

Etymology was also much debated in antiquity; but the explanations given to

changes in the meaning and form of words were marred on the one hand by their

belief that semantic evolution was always unidirectional, from a supposedly "correct"

initial meaning, to their corruption, and, on the other hand, by their disregard of

phonetic laws (Stati, 1971: 182).

During the Middle Ages, it is worth mentioning in the field of linguistics and

semantics the activity of the "Modistae" the group of philosophers so named because

of their writings On the Modes of Signification. These writings were highly

speculative grammars in wich semantic considerations held an important position. The

"Modistae" adopted the "thesei" point of view in the "physei-thesei" controversy and

their efforts were directed towards pointing out the "modi intelligendi", the ways in

which we can know things, and the "modi significandi", the various ways of

signifying them (Dinneen, 1967: 143).

It may be concluded that throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, and

actually until the 19th century almost everything that came to be known about meaning

in languages was the result of philosophic speculation and logical reasoning.

Philosophy and logic were the two important sciences which left their strong impact

on the study of linguistic meaning.

It was only during the 19th century that semantics came into being as an

independent branch of linguistics as a science in its own right. The first words which

confined themselves to the study of semantic problems as we understand them today,

date as far back as the beginning of the last century.

In his lectures as Halle University, the German linguist Ch. C. Reisig was the

first to formulate the object of study of the new science of meaning which he called

semasiology. He conceived the new linguistic branch of study as a historical science

studying the principles governing the evolution of meaning.

Towards the end of the century (1897), M. Bréal published an important book

Essay de sémantique which was soon translated into English and found an immediate

echo in France as well as in other countries of Europe. In many ways it marks the

birthday of semantics as a modern linguistic discipline. Bréal did not only provide the

name for the new science, which became general in use, but also circumscribed more

clearly its subject-matter.

The theoretical sources of semantic linguistics outlined by Bréal are, again,

classical logic and rethorics, to which the insights of an upcoming science, namely,

psychology are added. In following the various changes in the meaning of words,

interest is focused on identifying certain general laws governing these changes. Some

of these laws are arrived at by the recourse to the categories of logic: extension of

meaning, narrowing of meaning, transfer of meaning, while others are due to a

psychological approach, degradation of meaning and the reverse process of elevation

of meaning.

Alongside these theoretical endeavours to "modernize" semantics as the

youngest branch of linguistics, the study of meaning was considerably enhanced by

the writing of dictionaries, both monolingual and bilingual. Lexicographic practice

found extensive evidence for the categories and principles used in the study of

meaning from antiquity to the more modern approaches of this science: polysemy,

synonymy, homonymy, antonymy, as well as for the laws of semantic change

mentioned above.

The study of language meaning has a long tradition in Romania. Stati

mentioned (1971: 184) Dimitrie Cantemir's contribution to the discussion of the

difference between categorematic and syncategorematic words so dear to the medieval

scholastics.

Lexicography attained remarkably high standards due mainly to B. P. Hasdeu.

His Magnum Etymologicum Romaniae ranks with the other great lexicographic works

of the time.

In 1887, ten years ahead of M. Bréal, Lazar Saineanu published a remarkable

book entitled Incercare asupra semasiologiei limbei romane. Studii istorice despre

tranzitiunea sensurilor. This constitutes one of the first works on semantics to have

appeared anywhere. Saineanu makes ample use of the contributions of psychology in

his attempts at identifying the semantic associations established among words and the

"logical laws and affinities" governing the evolution of words in particular and of

language in general.

Although it doesn't contain an explicit theory of semantics, the posthumous

publication of Ferdinand de Saussure's Cours de linguistique générale 1916, owing to

the revolutionary character of the ideas on the study of language it contained,

determined an interest for structure in the field of semantics as well.

Within this process of development of the young linguistic discipline, the

1921-1931 decade has a particular significance. It is marked by the publication of

three important books: Jost Trier, Der Deutsche Wortschatz im Sinnbezink des

Verstandes (1931), G. Stern, Meaning and Change of Meaning (1931) and C. K.

Ogden and J. A. Richards: The Meaning of Meaning (1923).

Jost Trier's book as well as his other studies which are visibly influenced by

W. von Humbold's ideas on language, represents an attempt to approach some of the

Saussurean principles to semantics. Analyzing the meaning of a set of lexical elements

related to one another by their content, and thus belonging to a semantic "field", Trier

reached the conclusion that they were structurally organized within this field, in such a

manner that the significative value of each element was determined by the position

which it occupied within the respective field. For the first time, therefore, words were

no longer approached in isolation, but analyzed in terms of their position within a

larger ensemble - the semantic field - which in turn, is integrated, together with other

fields, into an ever larger one. The process of subsequent integrations continues until

the entire lexicon is covered. The lexicon therefore is envisaged as a huge mosaic with

no piece missing.

Gustav Stern's work is an ambitious attempt at examining the component

factors of meaning and of determining, on this ground, the causes and directions of

changes of meaning. Using scientific advances psychology (particularly Wundt's

psychlogy) Stern postulates several classifications and principles which no linguist

could possibly neglect.

As regards Ogden and Richard's book, its very title The Meaning of Meaning

is suggestive of its content. The book deals for the most part with the different

accepted definitions of the word "meaning", not only in linguistics, but in other

disciplines as well, identifying no less than twenty-four such definitions. The overt

endeavour of the authors is to confine semantic preoccupations to linguistic problems

exclusively. The two authors have the merit of having postulated the triadic relational

theory of meaning - graphically represented by the triangle that bears their names.

A short supplement appended to the book: The Problem of Meaning in

Primitive Languages due to an anthropologist, B. Malinowski, was highly

instrumental in the development of a new "contextual" theory of meaning advocated

by the British school of linguistics headed by J. R. Firth.

The following decades, more specifically the period 1930-1950 is known as a

period of crisis in semantics. Meaning was all but completely ignored in linguistics

particularly as an effect of the position adopted by L. Bloomfield, who considered that

the study of meaning was outside the scope of linguistics proper. Its study falls rather

within the boundaries of other sciences such as chemistry, physics, etc., and more

especially psychology, sociology or anthropology. The somewhat more conciliatory

positions which, without denying the role of meaning in language nevertheless alloted

it but a marginal place within the study of language (Hockett, 1958), was not able to

put an end to this period of crisis.

Reference to semantics was only made in extremis, when the various linguistic

theories were not able to integrate the complexity of linguistic events within a unitary

system. Hence the widespread idea of viewing semantics as a "refuge", as a vast

container in which all language facts that were difficult to formalize could be disposed

of.

The picture of the development of semantics throughout this period would be

incomplete, were it not to comprise the valuable accumulation of data regarding

meaning, all due to the pursuing of tradition methods and primarily to lexicographic

practice.

If we view the situation from a broader perspective, it becomes evident that the

so-called "crisis" of semantics, actually referred to the crisis of this linguistic

discipline only from a structuralist standpoint, more specifically from the point of

view of American descriptivism. On the other hand, however, it is also salient that the

renovating tendencies, as inaugurated by different linguistic schools, did not

incorporate the semantic domain until very late. It was only in the last years of the

sixties that the organized attacks of the modern linguistic schools of different

orientations was launched upon the vast domain of linguistic meaning.

At present meaning has ceased to be an "anathema" for linguistics. Moreover,

the various linguistic theories are unanimous in admitting that no language description

can be regarded as being complete without including facts of meaning in its analysis.

A specific feature of modern research in linguistics is the ever growing interest

in problems of meaning. Judging by the great number of published works, by the

extensive number of semantic theories which have been postulated, of which some are

complementary, while some other are directly opposed, we are witnessing a period of

feverish research, of effervescence, which cannot but lead to progress in semantics.

An important development in the direction of a psycholinguistic approach to

meaning is Lakoff's investigation of the metaphorical basis of meaning (Lakoff and

Johnson 1980). This approach draw on Elinor Rosch's notion of protype, and adopt

the view opposed to that of Chomsky, that meaning cannot be easily separated from

the more general cognitive functions of the mind.

G. Leech considers that the developments which will bring most rewards in

the future will be those which bring into a harmonious synthesis the insights provided

by the three disciplines which claim the most direct and general interest in meaning:

those of linguistics, philosophy and psychology.

2. Definition and Object of Semantics

In linguistic terminology the word semantics is used to designate the science of

word-meaning. The term, however, has acquired a number of senses in contemporary

science. Also, a number of other terms have been proposed to cover the same area of

study, namely the study of meaning. As to meaning itself, the term has a variety of

uses in the metalanguage of several sciences such as logic, psychology, linguistics,

and more recently semiotics.

All these factors render it necessary to discuss on the one hand the terminology

used in the study of meaning and on the other hand, the main concerns of the science

devoted to the study of meaning.

One particular meaning of the term semantics is used to designate a new

science, General Semantics, the psychological and pedagogical doctrine founded by

Alfred Korzybsky (1933) under the influence of contemporary neo-positivism.

Starting from the supposed exercise upon man's behaviour, General semantics aims at

correcting the "inconsistencies" of natural language as well as their tendency to

"simplify" the complex nature of reality.

A clearer definition of the meaning (or meanings) of a word is said to

contribute to removing the "dogmatism" and "rigidity" of language and to make up for

the lack of emotional balance among people which is ultimately due to language. This

school of thought holds that the study of communicative process can be a powerful

force for good in the resolution of human conflict, whether on an individual, local, or

international scale. This is a rather naïve point of view concerning the causes of

conflicts (G. Leech 1990: XI). Yet, certain aspects of the relationship between

linguistic signs and their users - speakers and listeners alike - have, of course, to be

analyzed given their relevance for the meaning of the respective signs.

Also, that there is a dialectic interdependence between language and thought in

the sense that language does not serve merely to express thought, but takes an active

part in the very moulding of thought, is beyond any doubt.

On the whole, however the extreme position adopted by general semanticists

as evidenced by such formulations as "the tyranny of words", "the power of language",

"man at the mercy of language", etc. has brought this "science" to the point of ridicule,

despite the efforts of genuine scholars such as Hayakawa and others to uphold it.

In the more general science of semiotics, the term semantics is used in two

senses:

(a) theoretical (pure) semantics, which aims at formulating an abstract theory of

meaning in the process of cognition, and therefore belongs to logic, more precisely

to symbolic logic;

(b) empirical (linguistic) semantics, which studies meaning in natural languages, that

is the relationship between linguistic signs and their meaning. Obviously, of the

two types of semantics, it is empirical semantics that falls within the scope of

linguistics.

The most commonly agreed-upon definition of semantics remains the one

given by Bréal as "the science of the meanings of words and of the changes in their

meaning". With this definition, semantics is included under lexicology, the more

general science of words, being its most important branch.

The result of research in the field of word-meaning usually takes the form of

dictionaries of all kinds, which is the proper object of the study of lexicography.

The term semasiology is sometimes used instead of semantics, with exactly the

same meaning. However since this term is also used in opposition to onomasiology it

is probably better to keep it for this more restricted usage. Semasiology stands for the

study of meaning starting from the "signifiant" (the acoustic image) of a sign and

examining the possible "signifiés" attached to it. Onomasiology accounts for the

opposite direction of study, namely from a "signifié" to the various "signifiants" that

may stand for it.

Since de Saussure, the idea that any linguistic form is made up of two aspects a material one and an ideal one -, the lingistic sign being indestructible union between

a signifiant and a signifié, between an expression and a content. In the light of these

concepts, the definition of semantics as the science of meaning of words and of the

changes in meaning, appears to be rather confined. The definition certainly needs to

be extended so as to include the entire level of the content of language. As Hjelmslev

pointed out, there should be a science whose object of study should be the content of

language and proposed to call it plerematics. Nevertheless all the glossematicians,

including Hjelmslev continued to use the older term - semantics in their works.

E. Prieto (1964) calls the science of the content of language noology (from

Greek noos - "mind") but the term has failed to gain currency.

Obviously, a distinction should be made between lexosemantics, which studies

lexical meaning proper in the traditional terminology and morphosemantics, which

studies the grammatical aspect of word-meaning.

With the advent of generative grammar emphasis was switched from the

meaning of words to the meaning of sentences. Semantic analysis will accordingly be

required to explain how sentences are understood by the speakers of language. Also,

the task of semantic analysis is to explain the relations existing among sentences, why

certain sentences are anomalous, although grammatically correct, why other sentences

are semantically ambiguous, since they admit of several interpretations, why other

sentences are synonymous or paraphrases of each other, etc.

Of course, much of the information required to give an answer to these

questions is carried by the lexical items themselves, and generative semantics does

include a representation of the meaning of lexical elements, but a total interpretation

of a sentence depends on its syntactic structure as well, more particularly on how

these meanings of words are woven into syntactic structure in order to allow for the

correct interpretation of sentences and to relate them to objective reality. In the case of

generative semantics it is obvious that we can speak of syntactic semantics, which

includes a much wider area of study that lexical semantics.

3. Semantics and Semiotics

When the Stoics identified the sing as the constant relationship between the

signifier and the signified they actually had in mind any kind of signs not just

linguistic ones. They postulated a new science of signs, a science for which a term

already existed in Greek: sêmeiotikê. It is however, only very recently, despite

repeated attempts by foresighted scientists, that semiotics become a science in its own

right.

A first, and very clear presentation of semiotics is it to be found in this

extensive quotation from John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

In the chapter on the "division of the sciences", Locke mentions "the third branch

(which) may be called semiotic, or the doctrine of signs... the business whereof is to

consider the nature of signs the mind makes use of for the understanding of things, or

conveying its knowledge to others. For, since the things the mind contemplates are

none of them, beside itself, present to the understanding, it is necessary that something

else, a sign or representation of the thing it considers, should be present to it" (Locke,

1964: 309).

Later, in the 19th century, the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce

devoted a life time work, which unfortunately remained unheeded for a long time, to

the study of signs, to setting up semiotics as a science, "as the doctrine of the essential

nature and fundamental varieties of possible «semiosis»". (R. Jakobson, 1965: 22).

Ferdinand de Saussure too, probably quite independently from Peirce, but

undoubtedly inspired by the same Greek philosophers' speculations on language,

suggested that linguistics should be regarded as just one branch of a more general

science of sign systems which he called semiology. In other words he saw no basic

difference between language signs and any other kinds of sings all of them

interpretable by reference to the same general science of signs.

Peirce distinguished three main types of signs according to the nature of the

relationship between the two inseparable aspects of a sign: the signans (the material

suport of the sign, its concrete manifestation) and the signatum (the thing signified):

(i)

Icons in which the relationship between the signans and the signatum is

one of the similarity.

The signans of an iconic type of sign, resembles in shape its signatum.

Drawings, photographs, etc., are examples of iconic signs. Yet, phisical similarity

does not imply true copying or reflection of the signatum by the signans. Peirce

distinguished two subclasses of icons-images and diagrams. In the case of the latter, it

is obvious that the "similarity" is hardly "physical" at all. In a diagram of the rate of

population or industrial production growth, for instance, convention plays a very

important part.

(ii)

Indexes, in which the relationship between the signans and the

signatum is the result of a constant association based on physical contiguity not on

similarity. The signans does not resemble the signatum to indicate it. Thus smoke is

an index for fire, gathering clouds indicate a coming rain, high temperature is an index

for illness, footprints are indexes for the presence of animals, etc.

(iii)

Symbols, in which the relationship between the signans and the

signatum is entirely conventional. There is no similarity or physical contiguity

between the two. The signans and signatum are bound by convention; their

relationship is an arbitrary one. Language signs are essentially symbolic in nature.

Ferdinand de Saussure clearly specified absolute arbitrariness as "the proper condition

of the verbal sign".

The act of semiosis may be both motivated and conventional. If semiosis is

motivated, than motivation is achieved either by contiguity or by similarity.

Any system of signs endowed with homogeneous significations forms a

language; and any language should be conceived of as a mixture of signs.

Another aspect revealed by semiotics which presents a particular importance

for semantics is the understanding of the semiotic act as an institutional one.

Language itself, can be regarded as an institution (Firth, 1957), as a complex form of

human behaviour governed by signs. This understanding of language opens the way

for a new, intentional theory of meaning. Meaning is achieved therefore either by

convention or by intention.

Bibliography:

1. Chiţoran, Dumitru. 1973. Elements of English Structural Semantics. Bucureşti:

E.D.P.

2. Leech, G. 1990. Semantics. The Study of Meaning. London: Penguin Books.

3. Saeed, J., I. 1997. Semantics. Dublin: Blackwell Publishers.

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION

1. Define semantics and its object.

2. The physei-thesei controversy.

3. Types of signs.

Chapter II

THE PROBLEM OF MEANING

I. The concept of meaning 1.a bipolar relation

2. a triadic relation - A. referential approach

- B. conceptual approach

3. Heger’s view.

II. Dimensions of meaning 1. dimensions of meaning

2. types of meaning in Leech’ s conception.

I.1. Any progress in semantics is conditioned by a clearer understanding of

meaning, as the object of its analysis. Numberless definitions of language meaning

have been postulated, some complementary in nature, some opposed. A linguistic

account

of meaning would still be very difficult to give because of the plurality of

levels at which meaning can be discussed- the word level, the phrase level, the

sentence level.

Even if the morpheme is the minimum unit of language endowed with

meaning, it is the word, the next higher unit that traditional lexicology has selected as

its object of study and to clearly understand the factors involved in meaning, it’s

necessary to begin with an account of meaning at word level.

The concept of meaning, defined by F. de Saussure, was first regarded as a

bipolar relation between the two interdependent sides of a linguistic sign-significans

‘expression’ and significatum ‘cont3ent’ and this is true for any sign, no matter to

what semiotic system it belongs.

2.

Ogden and Richards have pointed out in 1923 that at least three factors are

involved in any symbolic act- the symbol itself ‘the material aspect of the linguistic

sign, be it phonic or graphic’; the thought/reference ‘the mental content that

accompanies the occurrence of the symbol in the minds of both the speaker and the

listener’; the object itself/ the referent ‘the object in the real world designated by the

symbol’.

The triadic concept of meaning was represented by Ogden and Richards in the

form of a triangle.

While the relation symbol- reference and reference- referent are direct and

causal ones in the sense that the symbol expresses or symbolises the reference which,

in turn refers to the referent, the relation symbol- object or referent is an imputed,

indirect one.

Of the two sides of the triangle only the right-hand one can be left out –

tentatively and temporarily- in a linguistic account of meaning. The relationship

between thought and the outside world of objects and phenomena is of interest

primarily to psychologists and philosophers, linguists directing their attention towards

the other two sides. (Chiţoran, 1973: 30).

Depending on what it is understood by meaning, we can distinguish two main

semantic theories:

- the referential / denotational approach-meaning is the action of putting

words into relationship with the world;

- the representational /conceptual approach-meaning is the notion, the

concept or the mental image of the object or situation in reality as reflected in man’s

mind.

The two basic types of meaning were first mentioned by S. Stati in 1971referential definitions which analyse meaning in terms of the relation symbol- object

/referent; conceptual definitions which regard the relation symbol- thought/reference.

A. Denotational /Referential Theories of Meaning.

Before describing the characteristics of these theories, a clarification of the

terms used is necessary. All languages allow speakers to describe or model aspects of

what they perceive. In semantics the action of picking out or identifying individuals/

locations with words is called referring/denoting. To some linguists the two terms,

denote and refer are synonymous. J. Saeed (1997: 23) gives two examples of proper

names whose corresponding referents are easily recognizable

e. g. I saw Michael Jackson on TV last night.

We have just flown back from Paris.

The underlined words refer to/denote the famous singer, respectively the capital of

France, even if in some contexts they may be used to designate a person different from

the singer, or a locality other than the capital of France.

To John Lyons the terms denote and refer are not synonymous. The former is

used to express the relationship linguistic expression- world, whereas the latter is used

for the action of a speaker in picking out entities in the world. In the example

A sparrow flew into the room.

A sparrow and the room are NPs that refer to things in the world.; room,

sparrow denote classes of items. In conclusion, referring is what speakers do and

denoting is a property of words. Denotation is a stable relationship in a language, it

doesn’t depend on anyone’s use of the word unlike the action of referring.

Returning to the problem of theories of meaning, they are called referential/

denotational when their basic premise is that we can give the meaning of words and

sentences by showing how they relate to situations- proper names denote individuals,

nouns denote entities or sets of individuals, verbs denote actions, adverbs denote

properties of actions, adjectives denote properties of individuals-.In case of sentences,

they denote situations and events. The difference in meaning between a sentence and

its negative counterpart arises from the fact that they describe two situations

e. g.

There is a book on the shelf.

There isn’t a book on the shelf.

Referential theories consider meaning to be something outside the world itself, an

extra-linguistic entity. This means reducing the linguistic sign, i. e. the word to its

material aspect, be it phonic or graphic.

The impossibility of equating meaning with the object denoted by a given

word can be explained considering three major reasons

a. the identity meaning-object would leave meaning to a large extent undefined

because not all the characteristic traits of an object as an extra- linguistic reality

are identical with the distinctive features of lexical meaning;

b. not all words have a referent in the outside world; there are:

- non- referring expressions so, very, maybe, if, not, etc.

- referring expressions used generically:

e. g. A murder is a serious felony.

- words like nouns, pronouns with variable reference depending on the

context:

e. g. The president decides on the foreign policy.

She didn’t know what to say.

- words which have no corresponding object in the real world in general or

at a certain moment:

e. g. The unicorn is a mythical animal.

She wants to make a cake this evening.

- different expressions/words that can be used for the same referent, the

meaning reflecting the perspective from which the referent is viewed

e. g. The morning star is the same thing as the evening star.

The president of the USA/ George Bush/ Barbara Bush’s husband

was to deliver a speech.

Besides the referential differences between expressions, we can make useful

distinctions among the things referred to by expressions-referent = thing picked out by

uttering the expression in a particular context; extension of an expression = set of

things which could possibly be the referent of that expression. In Lyon’s terminology

the relationship between an expression and its extension is called denotation.(Saeed

1997: 27)

A distinction currently made by modern linguists is that between the

denotation of a word and the connotations associated with it. For most linguists,

denotation represents the cognitive or communicative aspect of meaning (Schaff

1965), while connotation stands for the emotional overtones a speaker usually

associates with each individual use of a word. Denotative meaning accounts for the

relationship between the linguistic sign and its denotatum. But one shouldn’t equate

denotation with the denotatum.What is the denotation of a word which has no

denotatum.

As far as the attitude of the speaker is concerned, denotation is regarded as

neutral, since its function is simply to convey the informational load carried by a

word. The connotative aspects of meaning are highly subjective, springing from

personal experiences, which a speaker has had of a given word and also from his/her

attitude towards his/ her utterance and/ or towards the interlocutors (Leech, 1990: 14).

For example dwelling, house, home, abode, residence have the same denotation but

different connotations.

Given their highly individual nature, connotations seem to be unrepeatable but,

on the other hand, in many instances, the social nature of individual experience makes

some connotative shades of meaning shared by practically all the speakers of a

language. It is very difficult to draw a hard line between denotation and connotation in

meaning analysis, due to the fact that elements of connotation are drawn into what is

referred to as basic, denotative meaning. By taking into account connotative overtones

of meaning, its analysis has been introduced a new dimension, the pragmatic one.

Talking about reference involves talking about nominals- names and noun

phrases-. They are labels for people, places, etc. Context is important in the use of

names; names are definite in that they carry the speaker’s assumption that his/ her

audience can identify the referent (Saeed, 1997: 28).

One important approach in nominals’ analysis is the description theory

(Russel, Frege, Searle). A name is taken as a label or shorthand for knowledge about

the referent, or for one or more definite descriptions in the terminology of

philosophers. In this theory, understanding a name and identifying the referent are

both dependent on associating the name with the right description.

e. g. Christopher Marlowe / the writer of the play Dr. Faustus / the Elizabethan

playwright murdered in a Deptford tavern.

Another interesting approach is the causal theory (Devitt, Sterelny, 1987) and

based on the ideas of Kripke (1980) and Donnellan (1972). This theory is based on the

idea that names are socially inherited or borrowed. There is a chain back to the

original naming/ grounding. In some cases a name does not get attached to a single

grounding. It may arise from a period of repeated uses. Sometimes there are

competing names and one wins out. Mistakes can be made and subsequently fixed by

public practice. This theory recognizes that speakers may use names with very little

knowledge of the referent, so it stresses the role of social knowledge in the use of

names. The treatment chosen for names can be extended to other nominals like

natural kinds (e. g. giraffe, gold) that is nouns referring to classes which occur in

nature.

B. Conceptual/ Representational Theory of Meaning

It proposes to define meaning in terms of the notion, the concept or the mental

image of the object or situation in reality as reflected in man’s mind. Semantic studies,

both traditional and modern, have used mainly such conceptual definitions of

meaning, taking it for granted that for a correct understanding of meaning, it is

necessary to relate it to that reflection in our minds of the general characteristics of

objects and phenomena. Even Bloomfield refers to general characteristics of an

object/ situation which is ‘linguistically relevant’.

On the other hand, complete identification of meaning with the concept or

notion is not possible either. This would mean to ignore denotation and to deprive

meaning of any objective foundation. More than that, languages provide whole

categories of words-proper names, prepositions, conjunctions- for which no

corresponding notions can be said to exist. Even in the case of notional words, the

notion, the concept may be regarded as being both ‘wider’ and ‘narrower’ than

meaning. A notion, concept has a universal character, while the meaning of a word is

specific, defined only within a given language (Chiţoran, 1973: 32-33).

Signification and Sense. Meaning should be defined in terms of all the

possible relations characteristic of language signs. The use of a linguistic sign to refer

to some aspects of reality is a semiotic act. There are three elements involved in any

semiotic act- the sign, the sense, the signification.

Two distinguishable aspects of the content side of the sign can be postulatedits signification, the real object or situation denoted by the sign, i. e. its denotation and

a sense which expresses a certain informational content on the object or situation. The

relation between a proper name and what it denotes is called name relation and the

thing denoted is called denotation. ‘A name names its denotation and expresses its

sense.’ (Alonso Church)

Extensional and Intensional

Meaning. The definition of meaning by

signification is called extension in symbolic logic (Carnap, 1960) and what has been

called sense is equivalent to intension. Extension stands for the class of objects

corresponding to a given predicate, while intension is based on the property assigned

to the predicate (E. Vasiliu, 1970).

e. g. They want to buy a new car. (intensional meaning)

There is a car parked in front of your house. (extensional meaning)

C. The Trapezium of Heger.

Klaus Heger in his article Les bases metodologiques de l’onomasiologie

proposes a trapezium- like variant, which allows him to introduce new distinctions.

Heger noticed – as Greimas, adept of the triadic conception agreed- that signifiant +

signifie i. e. concept is different from the linguistic sign, because the content of an

expression is a semasiologic field, which is made up of more than one concept or

mental object. In its turn a concept can be expressed by means of several signifiants.

The model of Heger gives him the possibility to analyse the content, making

place for sememes and semes. Extralinguistic reality has two levels- the logical and/or

psychological level and the level of the external world (C. Baylon, P. Fabre, 1978:

132).

The term moneme (A. Martinet) is also used by Heger and represents the

minimal unit endowed with signification; a moneme is made up of morphemes which

are in a limited number and it also represents a lexeme, the number of lexemes in a

language being virtually infinite. In conclusion, a moneme is at the same time form of

expression like phonemes and form of content like sememes. It is significant and

signified. The signified depends on the structure of the language, but the concept on

the right side of the trapezium is independent.

The onomasiology starts from the concept and tries to find the linguistic

relations for one or several languages. It tries to find monemes which by means of

their significations or sememes express a certain concept. An onomasiological field

reprewsents the structure of all the sememes belonging to different signified, so to

different monemes, but making up one concept.

Semasiology analyses a signified associated by co- substantiality to one

moneme; so we deal with multiple significations or sememes.

Kurt Baldinger (1984: 131) comments on Heger’s trapezium, analysing the

succesive stages from the substance of expression level to the final content level.

II. Dimensions of Meaning.

1. Dimensions of Meaning. Meaning is so complex and there are so many

factors involved in it, that a complete definition would be impossible. We are dealing

with a plurality of dimensions characteristic of the content side of linguistic signs

(Chiţoran, 1973: 37).

There is a first of all a semantic dimension proper, which covers the denotatum

of the sign including also information as to how the denotatum is actually referred to,

from what point of view it is being considered. The first aspect is the signification, the

latter is its sense.

e. g. Lord Byron/ Author of Child Harold have similar signification and

different senses.

He is clever. /John is clever . He and John are synonymous expressions if the

condition of co- referentiality is met.

The logical dimension of meaning covers the information conveyed by the

linguistic expression on the denotatum, including a judgement of it.

The pragmatic dimension defines the purpose of the expression, why it is

uttered by a speaker. The relation emphasized is between language users and language

signs.

The structural dimension covers the structure of linguistic expressions, the

complex network of relationships among its component elements as well as between it

and other expressions.

2. Types of Meaning. Considering these dimensions, meaning can be analyzed

from different perspectives, of which G. Leech distinguished seven main types

(Leech, 1990: 9).

a. Logical/ conceptual meaning, also called denotative or cognitive meaning, is

considered to be the central factor in linguistic communication. It has a complex

and sophisticated organization compared to those specific to syntactic or

phonological levels of language. The principles of contrastiveness and constituent

structure – paradigmatic and syntagmatic axes of linguistic structure- manifest at

this level i. e. conceptual meaning can be studied in terms of contrastive features.

b. Connotative meaning is the communicative value an expression has by virtue of

what it refers to. To a large extent, the notion of reference overlaps with

conceptual meaning. The contrastive features become attributes of the referent,

including not only physical characteristics, but also psychological and social

properties, typical rather than invariable. Connotations are apt to vary from age to

age, from society to society.

e. g. woman

[capable of speech] [experienced in cookery]

[frail] [prone to tears]

[non- trouser- wearing]

Connotative meaning is peripheral compared to conceptual meaning, because

connotations are relatively unstable. They vary according to cultural, historical period,

experience of the individual. Connotative meaning is indeterminate and open- ended

that is any characteristic of the referent, identified subjectively or objectively may

contribute to the connotative meaning.

c. In considering the pragmatic dimension of meaning, we can distinguish between

social and affective meaning. Social meaning is that which a piece of language

conveys about the social circumstances of its use. In part, we ‘decode’ the social

meaning of a text through our recognition of different dimensions and levels of

style.

One account (Crystal and Davy, Investigating English Style) has recognized

several dimensions of socio-linguistic variation. There are variations according to:

- dialect i. e. the language of a geographical region or of a social class;

- time , for instance the language of the eighteenth century;

- province/domain I. e. the language of law, science, etc.;

- status i. e. polite/ colloquial language etc.;

- modality i. e. the language of memoranda, lectures, jokes, etc.;

- singurality, for instance the language of a writer.

It’s not surprising that we rarely find words which have both the same

conceptual and stylistic meaning, and this led to declare that there are no ‘true

synonyms’. But there is much convenience in restricting the term ‘synonymy’ to

equivalence of conceptual meaning. For example, domicile is very formal, official,

residence is formal, abode is poetic, home is the most general term. In terms of

conceptual meaning, the following sentences are synonymous.

e. g. They chucked a stone at the cops, and then did a bunk with the loot.

After casting a stone at the police, they absconded with the money.

In a more local sense, social meaning can include what has been called

The illocutionary force of an utterance, whether it is to be interpreted as a request, an

assertion, an apology, a threat, etc.

d. The way language reflects the personal feelings of the speaker, his/ her attitude

towards his/ her interlocutor or towards the topic of discussion, represents

affective meaning. Scaling our remarks according to politeness, intonation and

voice- timbre are essential factors in expressing affective meaning which is

largely a parasitic category, because it relies on the mediation of conceptual,

connotative or stylistic meanings. The exception is when we use interjections

whose chief function is to express emotion.

e. Two other types of meaning involve an interconnection on the lexical level of

language. Reflected meaning arises in cases of multiple conceptual meaning,

when one sense of a word forms part of our response to another sense. On

hearing, in a church service, the synonymous expressions the Comforter and the

Holy Ghost, one may react according to the everyday non- religious meanings of

comfort and ghost. One sense of a word ‘rubs off’ on another sense when it has a

dominant suggestive power through frequency and familiarity. The case when

reflected meaning intrudes through the sheer strength of emotive suggestion is

illustrated by words which have a taboo meaning; this taboo contamination

accounted in the past for the dying- out of the non- taboo sense; Bloomfield

explains in this way the replacement of cock by rooster.

f. Collocative Meaning consists of the associations a word acquires on account of the

meanings of words which tend to occur in its environment/ collocate with it.

e. g. pretty girl/ boy/ flower/ color

handsome boy/ man/ car/ vessel/ overcoat/ typewriter .

Collocative meaning remains an idiosyncratic property of individual words and it

shouldn’t be invoked to explain all differences of potential co- occurrence. Affective

and social meaning, reflected and collocative meaning have more in common with

connotative meaning than with conceptual meaning; they all have the same openended, variable character and lend themselves to analysis in terms of scales and

ranges. They can be all brought together under the heading of associative meaning.

Associative meaning needs employing an elementary ‘associationist’ theory of mental

connections based upon contiguities of experience in order to explain it. Whereas

conceptual meaning requires the postulation of intricate mental structures specific to

language and to humans, and is part of the ‘common system‘ of language shared by

members of a speech community, associative meaning is less stable and varies with

the individual’s experience. Because of so many imponderable factors involved in it,

associative meaning can be studied systematically only by approximative statistical

techniques. Osgood, Suci and Tannenbaum (The Measurement of Meaning, 1957),

proposed a method for a partial analysis of associative meaning. They devised a

technique – involving a statistical measurement device, - The Semantic Differential -,

for plotting meaning in terms of a multidimensional semantic space, using as data

speaker’s judgements recorded in terms of seven point scales.

Thematic Meaning means what is communicated by the way in which a

speaker/ writer organizes the message in terms of ordering, focus or emphasis.

Emphasis can be illustrated by word- order:

e.g. Bessie donated the first prize.

The first prize was donated by Bessie.

by grammatical constructions:

e. g. There’s a man waiting in the hall.

It’s Danish cheese that I like best.

by lexical means:

e. g. The shop belongs to him

He owns the shop.

by intonation:

e. g. He wants an electric razor.

Conclusions

a. meaning, as a property of linguistic signs, is essentially a relationconventional, stable, and explicit- established between a sign and the object in

referential definitions, or between the sign and the concept/ the mental image of the

object in conceptual definitions of meaning;

b. an important aspect of meaning is derived from the use that the speakers

make of it – pragmatic meaning, including the attitude that speakers adopt towards the

signs;

c. part of the meaning of linguistic forms can be determined by the position

they occupy in a system of equivalent linguistic forms, in the paradigmatic set to

which they belong- differential/ connotative meaning;

d. equally, part of the meaning can be determined by the position a linguistic

sign occupies along the syntagmatic axis- distributional/ collocative meaning;

e. meaning cannot be conceived as an indivisible entity; it is divisible into

simpler constitutive elements, into semantic features, like the ones displayed on the

expression level of language.

1. Conceptual Meaning

Associative meaning

2. Connotative Meaning

3. Social Meaning

4. Affective Meaning

5. Reflected Meaning

6. Collocative Meaning

7. Thematic Meaning

Logical, cognitive or

denotative content

What is communicated by

virtue of what language

refers to

What is communicated of

the social circumstances of

language use

What is communicated of

the feelings and attitudes

of the speaker/ writer

What is communicated

through association with

another sense of the same

expression

What is communicated

through association with

words tending to occur in

the environment of another

word

What is communicated by

the way in which the

message is organized in

terms of order and

emphasis

Topics for discussion and exercises

1. Characterize the referential theories of meaning.

2. Define the terms referent, extension, denotation, connotation. Give examples to

illustrate the definitions.

3. Identify and comment on the type of meaning of the bold words in terms of

extension and intension

An Opera Theatre in her town is her dream.

They are signing the contract.

‘Have you met the Pope ‘ ‘I have never met Giovanni Paolo II’.

I wanted to find a nice pair of glasses but there wasn’t any cheap enough.

Since he saw that film, he’s always been afraid of ghosts.

Ann was sad. She didn’t answer my greeting.

He bought a bar of chocolate.

Zorro is his favorite hero.

They have no money to travel abroad.

Every year, the mayor delivers a speech in the town square.

What we need is a group of volunteers.

4. Give examples for each type of meaning in Leech’s classification.

Chapter III.

MOTIVATION OF MEANING

Ferdinand de Saussure's apodictic statement: "the linguistic sign is arbitrary" in

the sense that there is no direct relationship between the sound sequence (the

signifiant) and the "idea" expressed by it (signifié) is taken for granted in the study of

language. The resumption of the discussion on the arbitrary character of the linguistic

sign in the late thirties and early forties proved however that the problem is not as

simple as it might seem. There are numerous words in all languages in which a special

correlation may be said to exist between meaning and sound. These words include in

the first place interjections and onomatopoeia, which are somehow imitative of nonlinguistic sounds as well as those instances in which it can be said that some sounds

are somehow associated with certain meanings, in the sense that they suggest them.

This latter aspect is known as phonetic symbolism.

But in addition to these cases which still remain marginal in the language,

there is also another sense in which the meaning of words may be said to be related to

its form, namely the possibility of analyzing linguistic signs by reference to the

smaller meaningful elements of which they are made up. Indeed, derivative, complex

and compound words are analyzable from the point of view of meaning in terms of

their constituent morphemes.

It is obvious that while the general principle remains valid, namely that there is

no inherent reason why a given concept should be paired to a given string of sounds, it

is the linguist's task to examine those instances, when it is possible to say something

about the meaning of a linguistic sign by reference to its sounds and grammatical

structure, in other words, it is necessary to assess the extent to which there is some

motivation in the case of at least a number of words in the language.

Ullmann (1957) made a distinction between opaque and transparent words. In

the latter case of transparent words, Ullmann discusses three types of motivation:

phonetic, grammatical and semantic (motivation by meaning, as in the case of

"breakfast", whose meaning can be derived from the meaning of its component

elements).

There are two main types of linguistic motivation already postulated by de

Saussure: absolute and relative motivation.

1.

Absolute motivation

Absolute motivation includes language signs whose sound structure

reproduces certain features of their content. Given this quasi-physical resemblance

between their signifiant and their signifié, these signs are of an iconic or indexic

nature in the typology of semiotic signs, although symbolic elements are present as

well in their organization:

There are several classes of linguistic signs, which can be said to be absolutely

motivated:

(i) Interjections. It would be wrong to consider, as is sometimes done, that

interjections somehow depict exactly the physiological and psychological states they

express. The fact that interjections differ in sound from one language to another is the

best proof of it. Compare Romanian au! aoleu! vai! etc. and English ouch!, which

may be used in similar situations by speakers of the two languages.

(ii) Onomatopoeia. This is true of imitative or onomatopoeic words as well.

Despite the relative similarity in the basic phonetic substance of words meant to

imitate animal or other sounds and noises, their phonological structure follows the

rules of pattern and arrangement characteristic of each separate language. There are

instances in which the degree of conventionality is highly marked, as evidenced by the

fact that while in English a dog goes bow-wow, in Romanian it goes ham-ham. Also,

such forms as English whisper and Romanian şopti are considered to be motivated in

the two languages, although they are quite different in form.

(iii) Phonetic symbolism. Phonetic symbolism is based on the assumption that

certain sounds may be associated with particular ideas or meanings, because they

somehow seem to share some attributes usually associated with the respective

referents. The problem of phonetic symbolism has been amply debated in linguistics

and psychology and numerous experiments have been made without arriving at very

conclusive results.

It is quite easy to jump at sweeping generalizations starting from a few

instances of sound symbolism.

Jespersen attached particular attention to the phonetic motivation of words and

tried to give the character of law to certain sound and meaning concordances. He

maintained for instance, on the basis of ample evidence provided by a great variety of

languages, that the front, close vowel sound of the [i] type is suggestive of the idea of

smallness, rapidity and weakness. A long list of English words: little, slim, kid, bit,

flip, tip, twit, pinch, twinkle, click, etc. can be easily provided in support of the

assumption, and it can also be reinforced by examples of words from other languages:

Fr. petit, It. piccolo, Rom. mic, etc. Of course, one can equally easily find counter

examples - the most obvious being the word big in English - but on the whole it does

not seem unreasonable to argue that a given sound, or sequence of sounds is

associated to a given meaning impression, although it remains a very vague one.

Sapir (1929) maintained that a contrast can be established between [i] and [a]

in point of the size of the referents in the names of which they appear, so that words

containing [a] usually have referents of larger size. Similar systematic relations were

established for consonants as well.

Initial consonant clusters of the /sn/, /sl/, /fl/ type are said to be highly

suggestive of quite distinctive meanings, as indicated by long lists of words beginning

with these sounds.

2.

Relative motivation

Relative motivation. In the case of relatively motivated language signs, it is

not the sounds which somehow evoke the meaning; whatever can be guessed about

the meaning of such words is a result of the analysis of the smaller linguistic signs

which are included in them. Relative motivation involves a much larger number of

words in the language than absolute motivation. There are three types of relative

motivation: motivation by derivation; by composition and semantic motivation.

An analysis of the use of derivational means to create new words in the

language will reveal its importance for the vocabulary of a language. The prefix {-in},

realized phonologically in various ways and meaning either (a) not and (b) in, into,

appears in at least 2,000 English words: inside, irregular, impossible, incorrect,

inactive etc.

Similarly, the Latin capere ("take") appears in a great number of English

words: capture, captivity, capable, reception, except, principal, participant, etc.

It is no wonder that Brown (1964) found it possible to give keys to the

meanings of over 14,000 words, which can be analyzed in terms of combinations

between 20 prefixes and 14 roots. Some of his examples are given below:

Words

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Precept

Detain

Intermittent

Offer

Insist

Monograph

Epilogue

Aspect

Prefix

predeinterobinmonoepiad-

Common Meaning

before

away, down

between, among

against

into

alone, one,

upon

to, towards

Root

capere

tenere

mittere

ferre

stare

graphein

legein

specere

Common

Meaning

take, seize

hold, have

send

bear, carry

stand

write

say, study of

see

This table alone is sufficient to indicate the importance of relative motivation

for the analysis of meaning.

It is obvious that the lexicon of a language presents items which differ in the

degree to which their meaning can be said to be motivated; while some are opaque

(their sound give no indication of their meaning), others are more or less transparent,

in the sense that one can arrive at some idea of their meaning by recourse to their

phonetic shape or to their derivational structure or to some semantic relations which

can be established with other words in the language.

In Précis de sémantique française (1952), Ullman suggested several criteria of

semantic structure which enabled him to characterize English as a "lexical language",

as opposed to French which is a more "grammatical" one: the number of arbitrary and

motivated words in the vocabulary; the number of particular and generic terms; the

use of special devices to heighten the emotive impact of words. Three other criteria

are based on multiple meaning (patterns of synonymy, the relative frequency of

polysemy, and the incidence of homonymy) and a final one evaluates the extent to

which words depend on context for the clarification of their meaning. This is an area

of study which could be continued with profitable results for other languages as well.

Bibliography:

Chiţoran, Dumitru. 1973. Elements of English Structural Semantics, Bucureşti, Ed.

Didactică şi Pedagogică.

Exercises:

1. Give examples of words which are absolutely motivated.

2. Analyse the following words in terms of relative motivation: rowboat,

impermeability, wholesaler, pan-African, childless, playing-field, incredible,

scare-crow, counter-attack, imperfect, overdose, shareholder, caretaker,

salesman, foresee, misunderstanding.

3. Give examples of words build with the help of the following prefixes: bi-, in-,

mis-, de-, anti-, non-, out-, super-, dis-, mal-, a-, en-, over-.

4. Analyze the following blends in point of their relative motivation: sportcast,

smog, telescreen, mailomat, dictaphon, motel, paratroops, cablegram, guestar,

transistor.

5. Write the word forms of the following words and analyze them in terms of

relative motivation: move, comment, place. Consider Saussure’s types of

associations and find possible associations among the word forms that you

previously found.

Chapter IV

STRUCTURAL APPROACHE S TO THE STUDY OF ME ANING

1. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSI S

Though structuralism in linguistics should be connected to structuralism in

other sciences, notably in anthropology, it should also be regarded as a result of its

own inner laws of development as a science.

Generally, structuralist linguistics may

be characterised by a neglect of

meaning, but this must not lead to the conclusion that this direction in linguistics has

left the study of meaning completely unaffected. Structural research in semantics has

tried to answer two basic guestions:

a) – is there a semantic structure/system of language, similar to the systemic

organisation of language uncovered at other levels of linguistic analysis

(phonology and grammar) ?

b) can the same structure methods which have been used in the analysis of

phonological and grammatical aspects of languages be applied to the

analysis of meaning ?

In relation to question a), the existence of some kind of systemic organisation

within the lexicon of a language is taken for granted. F de Sanssure pointed aut that

the vocabulary of a language cannot be regarded as a mere catalogue. But this

aaceptance does not mean it is an easy job to prove the systematic character of the

lexicon. First of all, it would mean the study of the entire civilization it reflects and

secondly, given the fluid and vague nature of meaning, semantic reality must be

analysed without recourse to directly observable entities as it happens in case of sound

and grammatical meaning.

One solution was to group together those elements of the lexicon which form

more or less natural series. Such series are usually represented by kinship terms, parts

of the human body, the term of temporal and spatial orientation,etc, that can be said to

reveal a structural organisation. Structural considerations were applied to terms

denoting sensorial perceptions: colour, sound , swell, taste, as well as to terms of

social and personal appreciation.

The existence of such semantic series, the organisation of words into semnatic

fields justified the structural approach to the study of lexicon.

Hjelmslev conditioned the existencee of system in language by the existence

of paradignes so that a structural description is only possible where paradigmes are

revealed.But the vocabulary , as an open system, with a variable number of elements,

does not fit such a description unless the definition of system broadens. Melcuk

(1961) stated that a set of structurally organised objects forms a system if the objects

can be described by certain rules, on condition that the number of rules is smaller than

the number of objects. Constant reference to phonology, in terms of distinguishing

between relevant and irrelevant in the study of meaning has led to applying methods

pertaining to the expression level of language to its content level as well.

Some linguistic theories, mainly the Gloosemantic School, take it for granted

that there is an underlying isomorphism between the expression and content levels of

language. Accordingly they consider it axiomatic to apply a unique method of analysis

to both levels of language. Hjelmslev distinguishes between signification and sense

and deepens this distinction on the basis of a new dichotomy postulated by

glossematics : form and substance. While the sense refers to the substance of content,

signification refers to its form or structure. The distinction signification/sense can be

analysed in term of another structuralist dichotomy: invariant/variant. Significations

represent invariant units of meaning while the sense are its variants. There is a

commutation relation between significations as invariants, and a substitution one

between senses as variants. An example is given below :

Romanian

English

Russian

mana

hand

pyka

brat

arm

palma

Since significations as invariants find their material manifestation in senses as

their invariants, in terms of glossematics, a theory of signification stands for content

form alone, so signification is no more semantic than other aspects of content form

dealt with by grammar. It follows that only a theory of the sense (substance of content)

could be the object of study of semantics(Chitoran, 1973:48).

In Hjelmslev’s opinion, sense is characteristic of speech, not of language,

pertains to an empirical level, so below any interest of linguistics. Any attempt to

uncover structure or system at the sense level can be based on the collective

evaluation of sense. For Hjelmslev, lexicology is a sociological discipline which

makes use of linguistic material : words. This extreme position is in keeping with the

neopositivist stand adopted by glossematics, according to which form has primacy

over substance, that language is form, not substance and what matters in the study of

meaning is the complex network of relations obtaining among linguistic elements.

Keeping in mind the basic isomorphism between expression and content, it is

essential to emphasize some important differences between the two language levels:

-

the expression level of language implies sequentiality, a development in

time (spoken language) or space (written language); its content level is

characterised by simultaneity;

-

the number of units to be uncovered at the expression level is relatively

small, and infinitely greater at the content level.

It is generaly accepted that the meanings of a word are also structured, that

they form microsystems, as apposed to the entire vocabulary which represents the

lexical macrosystem. The meanings of a lexical element display three levels of

structure, starting from a basic significative nucleus, a semantic constant (Coteanu,

1960) which represents the highest level of abstraction in the structuration of

meaning. Around it different meanings can be grouped (the 2

nd

level). (Chiţoran,

1973:51)

The actual uses of a lexical item, resulting from the individualising function of

words (Coteanu, 1960) belong to speech. Monolingual dictionaries give the meanings

of a lexical item abstracted on the basis of a wide collection of data. As far as the

semantic constant is concerned, its identification is the task of semnatics and one way

of doing that is by means of the Componential Analysis.

Componential Analysis assumes that all meanings can be further analysed into

distinctive semantic features called semes, semantic components or semantic

primitives, as the ultimate components of meaning. The search for distinctive

semantic features was first limited to lexical items which were intuitively felt to form

natural structures of a more ar less closed nature. The set kinship terms was among the

first lexical subsystems to be submitted to componential analysis :

father [+male][+direct line] [+older generation]

mother [-male][+direct line] [+older generation]

son [+male][+direct line] [-older generation]

daughter [_male][+direct line] [-older generation]

uncle[+male][_direct line] [+older generation]

aunt [-male] [-direct line] [+older generation]

nephew [+male] [-direct line] [-older generation]

niece [-male] [-direct line] [-older generation]

It is evident than there exist the same hierarchy of units and the same principle

of structuring lower level units into higher level ones (Pottier, 1963):

Expression

Content

Distinctive feature

pheme (f)

seme (s)

Set of distinctive features

phememe(F)

sememe (S)

(a set of pheme)