Species group report card - seabirds and migratory shorebirds

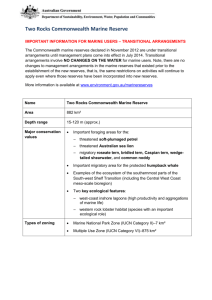

advertisement