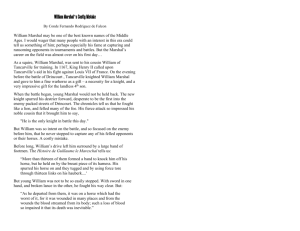

Knights: William Marshal

advertisement

KNIGHTS: WILLIAM MARSHAL The birth of a male child in a noble household was usually a reason for great rejoicing. But the celebrating was rather subdued when William Marshal was born. Had William been the first son, everyone in the castle would have been delighted because he would be the heir. But William was the fourth son—and his older brothers were healthy. His appearance in the world simply meant that this was one more child to be clothed, fed, and trained in the knightly pattern. He would not inherit anything. He would have to make his own way and seek his own fortune in the world. John Marshal, William’s father, was an English lord and knight. In 1152 King Stephen, who was fighting against Marshal’s lord, suddenly besieged a poorly defended castle that was under John Marshal’s protection. Marshal requested a truce from King Stephen so that he could appeal to his feudal lord. This was the usual procedure in such a situation. King Stephen agreed to a truce, provided Marshal would promise not to reinforce the castle or send in provisions. John Marshal promised. To show that he would keep his word, Marshal sent the king fiveyear-old William as a hostage. Then he promptly reinforced his castle with a large number of knights and archers and a plentiful supply of provisions. According to the customs of the time, William should have been killed because of his father’s failure to keep his word. However the king offered to spare William if John Marshal would surrender the castle. But Marshal, having three other sons and a good wife, considered his youngest son of far less value than a strong castle. He cheerfully told the king’s messenger that he cared little if William were hanged, for he had the anvils and hammers with which to forge still better sons. When King Stephen received this reply, he ordered his men to lead William to a convenient tree. Little William had no idea what was happening. When he saw one of the soldiers twirling a javelin, he asked him for the weapon. This reminder of William’s youth and innocence was too much for King Stephen. Taking the boy in his arms, the king carried him back to camp. Eventually peace was concluded between the warring parties and William Marshal returned to his parents. He remained there for only a few years. John Marshal decided to entrust his sons’ education to the lord of Tancarville in Normandy. So at the age of thirteen William left his home to begin his training as a knight. William served as a squire to the lord of Tancarville for eight years. During this time his main duty was to learn the art of fighting. He had to know how to handle the weapons of a knight—the spear, sword, and shield. In addition he had to know how to care for his equipment. A squire spent long hours tending his master’s horses and cleaning, polishing, and testing his arms and armor. Other qualities were also expected of a knight: The Church and the ideals of romantic love and service were starting to soften and polish the manners of the feudal aristocracy. For a long time the Church had demanded that a knight be pious; now ladies were demanding that he be courteous. If a squire hoped to be acceptable to the ladies, he must learn some more gentle art than that of smiting mighty blows. The manners and duties expected of a knight, the code and customs of knighthood, were known as chivalry. During the Crusades knights of southern Europe mingled with the rougher soldiers of northern France, Germany, and England. The men of the north, it was said, loved battle, but the southerners loved life. It was inevitable that some of this love of life—of milder pleasures, of love, of parties and dances and games—would rub off on the northerners. Besides, the Crusades brought into Europe more wealth and a greater desire for comfort. The new castles, built of stone as fortresses, were also carpeted and hung with tapestries or embroideries to keep out the chill. Even the songs promoted the change. Once the minstrels had sung only of war, of slashing off heads and breaking bones. But now they sang of love, sacrifice, and tenderness. They sang of knights whose first desires were to please their ladies, and of ladies who were the inspirations for gallant deeds. In a military society a youth comes of age when he is accepted as a full-fledged warrior. Every squire yearned to end his apprenticeship by receiving the insignia of knighthood. The squire followed his master to battles and tournaments, but he could not take an active part in combat. Being simply an attendant, he had no opportunity to win fame The occasion for which William had hoped came in the summer of 1167. War had broken out again, and the lord of Tancarville was called upon to send a force to help defend the town of Drincourt. The lord decided that this was a good time to knight William. William did not have to wait long for an opportunity to prove he was worthy to be a knight. Drincourt lay directly in the path of a large force of enemy knights. The lord of Tancarville rode forward rapidly from the walls of the town to meet the enemy. William Marshal, anxious to show his mettle, spurred forward at his leader’s side. The two parties met at full gallop with a thunderous shock. William’s lance was broken, but drawing his sword, he rushed into the midst of the enemy. Once William was caught by the shoulder with an iron hook and dragged from his horse, which was killed. With the townsmen’s help the enemy was completely routed. That night the lord of Tancarville held a great feast to celebrate the victory. As they discussed the incidents of battle, someone remarked that William had fought to save the town rather than to take prisoners who could pay him rich ransom. Shortly thereafter word came to Tancarville that a great tournament was to be held near Le Mans. The lord and his court received the news with joy. But William, who could not go without a horse, was very sorrowful. The lord, however, gave William a good horse, strong and fast. William never forgot the lesson. Never again did he neglect to capture good horses when he had the opportunity. On the appointed day a number of knights assembled to take part in the tournament. This tournament was not to be one of those mild affairs in which everything was arranged beforehand. It was a contest in which the defeated would lose all they possessed. After the knights had armed in the refuges provided at each end of the field, the two parties advanced toward one another in orderly ranks. William wasted no time in getting about the business of the day. Attacking one knight, he seized his horse by the rein and forced him out of the fight. Then after taking the knight’s pledge that he would pay his ransom, William returned to combat. He captured two more knights. By his success in this tournament, William not only showed his fighting skill, he recouped his finances as well. Each of the captured knights was forced to surrender all his equipment. William gained war horses, baggage horses, arms, and armor. It was a good beginning for a young knight. William had fought successfully in a battle and two tournaments. He had won some valuable property. He had learned the business of fighting, and he could make his living at it. William was well started on his knightly career.