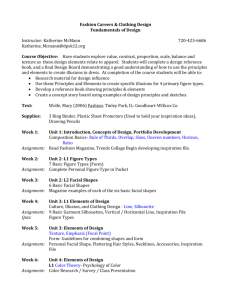

Sources of inspiration in industrial practice:

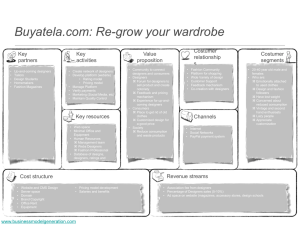

advertisement