Ultrasound Of The Urinary System And Prostate

advertisement

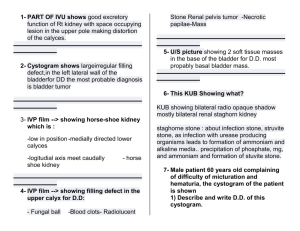

Ultrasound of the Urinary System and Prostate Alain Giroux, DVM, MSc, DACVR Introduction Ultrasound is an excellent imaging modality to evaluate the urinary tract. With ultrasonographic examination the entire urinary tract can be evaluated at one time and usually without the aid of anesthesia. The kidneys can be imaged using a 5.0-megahertz transducer; however, for small dogs and cats, a 7.5megahertz transducer is ideal. Normal Renal Anatomy The kidneys are located in the retroperitoneal space, usually between the caudal thoracic and 3rd lumbar vertebrae. The kidneys are bean-shaped and are composed of the renal capsule, renal cortex, renal medulla and the diverticuli. The renal pelvis is located in the central portion of the kidneys and is usually surrounded by renal fat (Fig. 1K and Fig. 2K). Renal arteries and veins can be identified at the hilus of the kidneys. The ureter leaves the renal pelvis through the hilus of the kidney. The normal ureter is not usually identified ultrasonographically. The left kidney is located caudal to the fundus of the stomach and medial to the spleen. The right kidney is caudal to the liver and is located in the renal fossa of the caudate lobe of the liver. The right kidney is further cranial than the left kidney, which makes visualizing the right kidney more difficult. The size of the kidneys varies depending on the size of the dog. A normal canine kidney can vary from 4 to 9 cm in length and feline kidneys are usually 3.8 to 4.4 cm in length. Figure 1K: Kidney Anatomy Figure 2K: Kidney Anatomy at the Pelvis 1 2 Ultrasonographic Renal Anatomy The capsule of the kidney is a hyperechoic structure which is identified surrounding the kidney. The renal cortex is hyperechoic in relation to the medulla. There is good distinction between the renal cortex and renal medulla in the normal kidney (Fig. 3Ka,b and Fig. 4K). The renal sinus (Fig.4K) usually contains fat which can be seen as bright echoes and in some cases can result in acoustic shadowing. The medulla of the kidney is separated into sections by the diverticuli. The renal cortex of the kidneys is usually less echogenic than the spleen but more echogenic than the renal medulla. The renal cortex can be isoechoic to hypoechoic in relationship to the liver. The renal artery and vein can usually be visualized entering the kidney at the renal sinus. Renal vessels can be recognized in the medulla. The arcuate and interlobar arteries can sometimes be visualized at the cortical medullary junction. When evaluating the kidneys ultrasonographically, the patient is usually placed in dorsal recumbency. The kidneys should be scanned in both sagittal and transverse planes. The appearance of the renal cortex and renal medulla will depend on where the sagittal and transverse images are obtained in relation to the midline of the kidney. Renal pelvic dilatation may be best visualized in the transverse plane (Fig. 5K and Fig. 6K). Figure 3Ka: Sagital View of Kidney: Centered on Hilus Figure 3Kb: Sagital View of Kidney: Centered Off Hilus Figure 4K: Transverse View of Kidney 3 Renal Abnormalities As with other organs, diseases of the kidneys are usually divided into focal and diffuse. The table 1K lists examples of ultrasonographic changes in the kidney with possible causes. Table 1K: Ultrasonographic Appearance of Common Renal Diseases Ultrasonographic Appearance Diseases Anechoic to hypoechoic lesions Renal cysts Polycystic renal disease Lymphosarcoma Increased echogenecity Renal infarcts Infection Nephrolithiasis Renal calculi Lymphosarcoma Various echogenic appearances Hematomas Abscesses Neoplasia Dilation of the renal pelvis Pyelonephritis Hydronephrosis Diuresis Altered renal architecture Renal dysplasia Neoplasia End-stage renal disease Anechoic fluid surrounding the kidneys Perinephrotic cyst Perirenal hemorrhage Extravasation of urine Figure 5K:Renal pelvis Dilatation: Sagital View Figure 6K:Renal Pelvis Dilatation: Transverse View 4 Urinary Bladder and Prostate Anatomy The urinary bladder is a hollow organ which stores urine. The size and location of the bladder is divided into the neck and body with the neck directly toward the pelvic canal and connected to the urethra (Fig. 7K). The ureters enter the bladder on the dorsocaudal aspect of the bladder just proximal to the neck of the bladder. The urinary bladder wall is composed of the serosa, muscular layer and mucosa. The prostate gland is located caudal to the urinary bladder. The prostate gland in a castrated patient may not be visualized. The prostate gland surrounds the pelvic urethra beginning at the trigone region of the urinary bladder. The prostate gland is a bi-lobe structure and is surrounded by a capsule. The size and position of the normal prostate gland varies with age, body size and perhaps the breed of dog. Figure 7K: Urinary Bladder and Prostate Anatomy: Dorsal View 5 Ultrasonographic Urinary Bladder and Prostate Anatomy The urinary bladder is identified as an anechoic structure in the caudal aspect of the abdomen. The urinary bladder is best evaluated when it is filled with urine. The urinary bladder wall should be uniform in thickness and the mucosal lining smooth in contour. Its wall contains layers that can be seen in ideal conditions as a double wall appearance (Fig. 9K). The normal prostate gland has a homogeneous parenchymal pattern with a medium to fine texture. The echogenicity is variable from hyperechoic to hypoechoic but should be uniform in echogenicity. Ultrasonographically, the individual lobes of the prostate gland can be visualized in the transverse plane. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the urinary bladder and prostate gland is usually performed with the patient in dorsal recumbency. A 7.5-megahertz transducer is ideal for evaluating the urinary bladder and prostate gland; however, in large dogs, a 5-megahertz transducer can be used to evaluate the prostate gland. Figure 8K: Normal Urinary Bladder Figure 9K: Normal Urinary Bladder: Double Wall Appearance Figure 10K: Normal Prostate: Neutered Male 6 Urinary Bladder Abnormalities Ultrasonographic abnormalities involving the urinary bladder usually include thickening of the urinary bladder wall which can be seen with cystitis or an infiltrative process such as neoplasia. Neoplastic lesions are most commonly identified in the trigone region and are usually due to a transitional cell carcinoma (Fig. 11K and 12K) but can be present anywhere. Severe thickening of the urinary bladder wall, especially in cats, has been associated with neoplasia, such as lymphosarcoma. The mucosal lining of the urinary bladder wall becomes irregular with cystitis (Fig. 13K). Cystitis usually involves the cranioventral aspect of the urinary bladder. Cystic calculi (Fig. 14K) or blood clots can be identified in the urinary bladder lumen and usually gravitate to the dependent portion of the urinary bladder wall. Evaluating the urinary bladder with the patient in various positions would be necessary to document that calculi or blood clots are free floating within the lumen. Cystic calculi are usually hyperechoic and result in acoustic shadowing (Fig. 14K). Figure 11K: Transitional Cell Carcinoma Figure 12K: Transitional Cell Carcinoma Figure 13K: Severe Cystitis Figure 14K: Calculus and Cystitis 7 Prostate Abnormalities Most of the disease processes involving the prostate gland result in enlargement of the prostate gland. Prostatic cysts appear as anechoic regions within the prostate gland with acoustic enhancement and can be of various sizes. Prostatic cysts (Fig 15K) must be separated from prostatic abscesses (Fig 16K). Prostatic abscesses usually contain echogenic material and are surrounded by a capsule. Periprostatic cysts are also associated with the prostate gland. Prostatic cysts or periprostatic cysts may be congenital or develop secondary prostatic hypertrophy or squamous metaplasia. Benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostatic infections can have a very similar appearance. Benign prostate hyperplasia and infection usually result in generalized enlargement of the prostate gland. Scattered hyperechoic foci and small cysts can be associated with prostatic hyperplasia; however, with prostatic inflammation, the parenchyma is usually heterogeneous with a mixed pattern of echogenicity. The prostate gland may become hypoechoic with infection. Mineralization is not usually associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia; however, with infection, hyperechoic areas secondary to fibrosis, gas or mineralization can be visualized. The prostatic capsule usually remains intact with both benign hyperplasia and infection. With prostatic neoplasia, the prostatic parenchyma has no specific ultrasonographic changes to differentiate neoplasia from infection or hyperplasia. Hyperechoic areas can be present throughout the parenchyma suggesting mineralization; however, caviar or cyst-like lesions can also be present. Differentiation of benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, or prostatic adenocarcinoma can be difficult based on the ultrasonographic appearance. A biopsy of the prostate gland may be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis. With prostatic neoplasia, evaluation of the sublumbar lymph nodes for changes to suggest metastasis is recommended. Figure 15K: Prostatic Cysts and Hyperplasia Figure 16K: Prostatic Abscess 8